199 Aortic Dissection

The initial observation and description of an aortic dissection was made by Morgagni in the 18th century. This was followed by multiple anatomic and postmortem reports, including the description of the cause of death of King George II of England shortly before the American Revolution.1 In the early 1800s, Maunoir better defined the pathologic process and first used the term dissection to describe the pathology.2 Although many subsequent reports have described aortic dissection, premorbid diagnosis was not consistently possible until refinements in contrast aortography were made.3 Indeed, only in the past several decades has either medical or surgical management had a reasonable chance to alter the course of aortic dissection.

The first attempts to treat this condition surgically involved wrapping of the dissected aorta to prevent rupture4 or treatment of the complications of dissection without definitive repair. This usually resulted in a catastrophic outcome and death. DeBakey and colleagues pioneered the surgical treatment of aortic disease, including dissection, and first reported graft replacement of the dissected aorta as definitive treatment.5 Aortic graft interposition has become the cornerstone of modern surgical therapy.

Classification

Classification

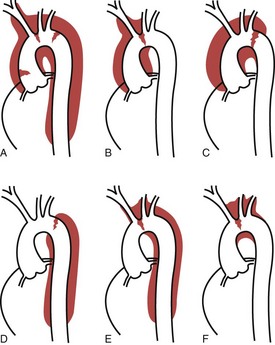

An understanding and description of aortic dissection are critical for the optimal care of these patients. The first widely used classification system was developed by DeBakey and colleagues and consists of three categories: types I, II, and III.5,6 Type I involves dissection originating in the ascending aorta, which continues to course through the descending aorta. Type II involves a tear only in the ascending aorta, and type III involves a tear originating in the descending thoracic aorta, distal to the ligamentum arteriosum. Subsequently, Daily and associates at Stanford University developed a classification system involving only two groupings, now known as the Stanford system.7 In the Stanford classification system (Figure 199-1), type A dissections involve the ascending aorta, and type B involves the aorta distal to the innominate artery. There have been many other attempts to classify aortic dissection, but most have been abandoned. Despite the fact that different categories are used, the essential element of a classification system of aortic dissection is involvement of the ascending aorta, regardless of the location of the primary intimal tear and irrespective of the distal extent of the dissection process.8 This functional classification approach is consistent with the pathophysiology of aortic dissection, considering that involvement of the ascending aorta is the principal predictor of the biological behavior of the disease process, including the most common fatal complications—rupture with tamponade, congestive heart failure, and myocardial infarction. Moreover, functional classification simplifies diagnosis, because it is easier to accurately identify involvement of the ascending aorta than to determine the exact site of the primary intimal tear or the total extent of propagation of the dissection process.

Over the past decade, advances in vascular imaging technology have led to the increased recognition of other conditions of the aorta, such as intramural hematoma and penetrating aortic ulcers, as distinct pathologic variants of classic aortic dissection.9,10 Both these entities are characterized by the lack of a classic intimal flap dividing the aortic lumen into true and false channels. Intramural hematoma can be precipitated by an atherosclerotic ulcer penetrating the aortic wall or can occur spontaneously without intimal disruption after rupture of the vasa vasorum. Intramural hematoma can involve the ascending aorta (type A) as well as the descending aorta (type B). Although it is possible, an intramural hematoma rarely evolves into an aortic dissection.11 Penetrating atherosclerotic ulcers occur most commonly in the descending thoracic aorta. Distinguishing intramural hematoma or penetrating aortic ulcer from aortic dissection is important because the prognosis and management of these lesions can differ.12,13

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

Aortic dissection can occur in all age-groups, although the majority of cases are observed in men aged 50 to 80 years. Dissection in patients younger than 40 years is most commonly an acute type A dissection and often occurs in patients with Marfan syndrome or a similar connective tissue disorder. On rare occasions, women during the last trimester of pregnancy or during delivery present with acute aortic dissection, presumably due to hormone-induced weakness of the aortic connective tissue and the markedly increased intraaortic pressure that often occurs during delivery. There is a male predominance, with an estimated male-to-female ratio of approximately 2 : 1. The exact incidence of aortic dissection is difficult to ascertain because in many cases, the diagnosis is not made before death. Indeed, delayed recognition of acute aortic dissection is a frequent cause of malpractice suits. In one series, acute aortic dissection was found in 1% to 2% of autopsies.14 Recently it has been estimated that the incidence of acute aortic dissection in the United States might be as high as 10 to 20 or more cases per million population per year.15 Most aortic dissections (two-thirds) occur in the ascending aorta (Stanford type A) as opposed to the less frequent distal Stanford type B dissections. Most caregivers incorrectly believe that ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms occur more commonly than aortic dissections; however, the former just tend to be diagnosed correctly more often than the latter.

The most consistent clinical condition associated with aortic dissection is arterial hypertension. In patients with aortic dissection, the prevalence of arterial hypertension varies between 45% and 80%16–19 and is highest in patients with acute type B dissection (Box 199-1). Hypertension may lead to smooth-muscle degeneration in the aortic wall, which may predispose to aortic dissection.

Connective tissue disorders such as Marfan or Ehlers-Danlos syndromes are associated with an increased risk of aortic dissection. Although both these conditions are relatively rare, they are frequently associated with acute dissection. In fact, aortic rupture or dissection is a common cause of death in patients with Marfan syndrome or other connective tissue disorders.20 In addition, aortic dissection is more common in patients with Turner’s syndrome and inflammatory disorders of the aorta such as syphilis or giant cell arteritis. Severe aortic atherosclerosis has been associated with a slight increase in the incidence of aortic dissection, but if dissection occurs, its extent seems to be more limited.

The risk of perioperative and late postoperative dissection21 is also increased in patients with a bicuspid aortic valve or aortic coarctation, presumably due to impaired connective tissue integrity. Aortic dissection is a rare complication of cardiac catheterization and other percutaneous diagnostic and therapeutic interventional techniques involving manipulation of catheters inside the thoracic aorta. Unfortunately, most veteran cardiac surgeons have experienced cases of intraoperative aortic dissection due to a clamp injury of the ascending aorta or a dissection initiating at the arterial cannulation site, especially when femoral arterial cannulation is performed.

One of the cardiovascular complications of cocaine use is acute aortic dissection, and this diagnosis should be considered in drug abusers presenting with acute chest pain.22,23 Aortic dissection in this setting occurs as a result of sudden severe hypertension secondary to catecholamine release.

Presentation

Presentation

Severe chest pain of a sudden nature is the most common presenting symptom of aortic dissection. The pain is typically abrupt and severe at onset and is often described as “tearing” and “the worst pain I have ever experienced.” This is especially true for patients who have never experienced childbirth. With type A dissections, the pain tends to be in the anterior chest and similar to that observed with myocardial infarction. Type B dissections classically cause midscapular pain, although this can be quite variable; this variability may lead to an incorrect diagnosis. Migration of pain and constant pain suggest continued expansion or progression. Differentiating the chest pain of acute aortic dissection from that of other causes such as acute myocardial ischemia, esophageal reflux disease, pericarditis, chest trauma, or abdominal pathology is critical in the initial evaluation of these patients to allow prompt, correct management. Unlike the crescendo-type pain frequently associated with acute myocardial infarctions, aortic dissections present with abrupt, sharp, unrelenting severe pain. On rare occasion, acute dissection can be painless, although this presentation is uncommon and is more often the case in patients presenting with chronic dissection. A relative minority of patients with acute aortic dissection present with signs of cardiac and other organ system involvement.17–19,24–26 Other clinical manifestations may include stroke, paraplegia, upper- or lower-extremity ischemia, and anuria or abdominal pain due to renal or mesenteric ischemia. These latter findings portend a grave prognosis.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of aortic dissection requires a strong index of suspicion by the evaluating caregiver. If the acute, sudden onset of chest pain cannot be attributed to myocardial infarction or ischemia, pericarditis, or traumatic chest injury, the diagnosis of acute dissection must be considered. Even in cases of acute myocardial infarction, the diagnosis of aortic dissection should still be entertained, especially if the patient develops migrating chest or back pain, leg ischemia, syncope, or other neurologic symptoms that may be related to vascular compromise. Physical findings often include a disparity in blood pressure measurements between the right and left arms or between the arms and legs, or a diminished pulse in one of the limbs. After the diagnosis is suspected, rapid confirmation or exclusion of aortic dissection is critical for optimal care. Until recently, aortic angiography was considered the gold standard for diagnosing acute dissection, because other methods such as computed tomography (CT) and echocardiography were untested or fraught with artifactual findings. However, improved computed tomography angiography (CTA), transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques are at least as accurate as aortic angiography and are usually far more rapidly obtained. Selection of the diagnostic method depends on which technique is most accurate and can be most quickly obtained in the treating hospital. In general, the procedure of choice is CTA; it is noninvasive and easy to perform and can usually be obtained without delay. Owing to major technologic advances, acquisition of a large number of thin-slice images is possible within minutes using ultrafast CT scanners. Further, modern computer technology allows complex reconstruction of high-quality images. The diagnosis of aortic dissection requires identification of two distinct lumens separated by an intimal flap.27 Contrast-enhanced CT scanning has a sensitivity of 82% to 100% and a specificity between 90% and 100%.17,27–32 Disadvantages include the need for intravenous contrast and the presence of artifacts, although the latter is now less of a problem than in the past.

MRI is accurate in making the diagnosis and is also noninvasive and does not require the use of contrast material. MRI produces high-quality images of the aorta in multiple planes and allows clear delineation of the entire aorta, localization of the intimal tear, delineation of aortic branch artery involvement, and diagnosis of a pericardial effusion suggestive of aortic rupture. As with CTA scanning, the criterion used to diagnose acute aortic dissection with MRI is identification of two lumina separated by an intimal flap. MRI is associated with sensitivity and specificity rates of 95% to 100%.17,27,29–32 In urgent circumstances, MRI may not be immediately available, and this approach should not be performed in patients with pacemakers, defibrillators, or other metallic implants. In addition, the relatively long time necessary for image acquisition in hemodynamically compromised patients is a potential drawback to using MRI in identifying an aortic dissection. The fact that the patient has to lie flat in the magnetic field can be problematic in some cases.

Treatment

Treatment

In general, all patients with acute type A aortic dissections should be considered for emergency surgical repair of the ascending aorta to prevent life-threatening conditions or complications.* Patients with acute type A dissection presenting with irreversible stroke or other severe malperfusion syndromes,8,18,36 those with debilitating systemic diseases such as metastatic cancer with a life expectancy of less than 1 year, or those older than 80 years with multiple major complications or serious medical conditions may be considered for medical management. It should be recognized, however, that patients treated nonoperatively are not likely to survive. The presence of acute hemiplegia alone should not be considered an absolute contraindication to early surgical intervention,36 because many of these patients recover significant neurologic function after surgery. However, patients presenting with hypotension, massive stroke, anuria, and acidosis suggestive of mesenteric ischemia should be considered nonsurgical candidates. Patients presenting with acute type A intramural hematoma are managed identically to those with acute type A aortic dissection.9,11,37 However, some authors believe that medical therapy is indicated for selected patients with uncomplicated acute type A intramural hematoma when the ascending aorta is not excessively dilated.38–40 If a patient with acute type A intramural hematoma is treated medically, close observation is mandatory. Serial imaging studies should be obtained over several days.

As soon as the diagnosis of acute type A aortic dissection is suspected, intensive monitoring must be initiated. An arterial line, central venous catheter, and urinary catheter should be inserted. Antihypertensive treatment is a major part of initial management of patients with acute type A or type B dissection, before and after surgical correction (Table 199-1). Generally, patients with acute severe hypotension or other evidence of rupture or impending rupture should be taken to the operating room emergently, and attempts at pericardial drainage should be avoided.

TABLE 199-1 Initial Medical Management for Patients with Acute Aortic Dissection

| Drug | Dosage |

|---|---|

| Metoprolol | 5-10 mg slow IV bolus until SBP <120 mm Hg and HR <70 bpm; repeat as needed |

| Esmolol | 500 µg/kg/min IV for 1 min, followed by 30-50 µg/kg/min for 5 min; titrate to maintain SBP <120 mm Hg systolic and HR <70 bpm |

| Labetalol | 0.25 mg/kg IV over 2 min; 40-80 mg q 10 min up to 300 mg; continuous IV infusion to maintain SBP <120 mm Hg and HR <70 bpm |

| Sodium nitroprusside | 1-8 µg/kg/min IV to maintain SBP <120 mm Hg; should be used in conjunction with a beta-blocker (metoprolol, esmolol, labetalol) |

bpm, beats per minute; HR, heart rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

The primary goal of surgical treatment for patients with acute type A dissection is to replace the ascending aorta to prevent aortic rupture or proximal extension of the process, with resultant tamponade or severe heart failure. Ideally, the primary intimal tear should be completely resected, and the dissected aortic layers reconstituted proximally and distally to obliterate the false lumen and reestablish normal perfusion to distal organs. When aortic valve regurgitation is present, aortic valve competence is restored either by reconstructing the sinuses of Valsalva and the aortic root or by resuspending the valve commissures. These approaches are possible in the majority of cases.41 Complete aortic root replacement with reimplantation of the coronary ostia using either a composite valve graft or a valve-sparing technique should be considered if the aortic root is severely damaged by the dissection process, the patient has Marfan syndrome or another connective tissue disorder, severe annuloaortic ectasia is present, or the valve needs to be replaced for other reasons such as aortic stenosis.42–44 In selected cases, aortic valve replacement and supracoronary aortic graft replacement may be used to treat acute type A aortic dissections if the aortic root is not destroyed by the dissection. Excellent surgical technique has to be used to prevent excessive bleeding, continued dissection, and residual coronary ischemia or aortic valve insufficiency. Tranexamic acid or ε-aminocaproic acid (Amicar) can be administered to decrease bleeding. Aprotinin, while often used in the past, is no longer available. When necessary, reinforcement of the dissected aortic layers is facilitated by reapproximation of the dissection flap to the aortic wall using strips of Teflon felt or bovine pericardium. Biological glue composed of purified bovine serum albumin and 10% glutaraldehyde was recently approved in the United States (BioGlue [CryoLife Inc., Kennesaw, Georgia]). Biological glue is easy to use and decreases blood loss,45 but cases have been reported in which use of a large amount of glue has resulted in development of false aneurysms, graft dehiscence, and full-thickness aortic necrosis. Most modern woven vascular grafts are not plagued by excessive bleeding and are easy to use.

In the past 15 years, the use of hypothermic circulatory arrest has been advocated to allow careful inspection of the aortic arch and performance of an “open” distal aortic anastomosis in cases of acute type A dissection.46,47 The construction of a completely hemostatic distal anastomosis is easier in the absence of an aortic cross-clamp. However, profound circulatory arrest increases the risk of neurologic injury, especially if the distal anastomosis cannot be performed in a rapid manner.

In up to a third of patients, the primary intimal tear is located in the aortic arch or descending aorta, a condition associated with a poorer prognosis.47–50 These tears should be resected if possible, but such resection is often not feasible without combining arch or distal aortic resection with ascending aortic repair. Elderly patients often do not tolerate such extensive surgery and sustain major complications. In addition, reentry tears may occur in the distal aorta, precluding establishment of a totally intact, normally perfused aorta at the end of the operation. Although failure to include the arch in the repair may increase the need for subsequent aortic reoperation and reduce long-term survival, most cardiovascular surgeons simply treat the most critical portion of the aorta (i.e., the ascending segment) in these cases and leave the remainder of the aorta alone in an effort to facilitate patient salvage. This strategy is especially reasonable for very elderly patients or those with major comorbid conditions. Although infrequently encountered, patients with chronic type A or type B dissection may need surgical repair or stent grafting if an aortic false aneurysm or progressive aortic enlargement has developed. In some cases, it is difficult to distinguish between acute and chronic type A aortic dissection. When this occurs, urgent repair should be undertaken. Aortic dilatation due to significant aortic valve insufficiency is an indication for operation. In asymptomatic patients, surgical intervention is generally recommended when the diameter of the ascending aorta is greater than 55 to 60 mm, depending on the size of the normal native aorta (50 mm in patients with Marfan syndrome), or if the documented rate of expansion is greater than 5 to 10 mm over 1 year.51

With optimal medical and surgical methods, patients with aortic dissection have a mortality of 5% to 30% in the best centers.* These relatively low early mortality rates reflect advances in early diagnosis, surgical techniques, and myocardial protection. In the Stanford experience, the overall survival rates for patients with acute type A dissections at 1, 5, and 10 years were 67%, 55%, and 37%, respectively.18 For patients with chronic type A dissections, the survival was 76%, 65%, and 45%, respectively. For patients with acute type A dissections, late survival for discharged patients was 91%, 75%, and 51% at 1, 5, and 10 years, respectively, compared with 93%, 79%, and 54% for those with chronic type A dissections. One-third of the late deaths were cardiac related, and many (10%-20%) were due to complications related to extension of the dissection or dilatation of the dissected aortic segment.

The treatment of Stanford type B dissections is generally medical, with aggressive antihypertensive and beta-blocker therapy and close long-term observation for progressive dilatation (see Table 199-1). Generally, beta blockade is initiated, and a vasodilator drug such as sodium nitroprusside is added later for blood pressure control. Pure vasodilator drugs should be avoided as an initial treatment, because reflex tachycardia and increased cardiac contractility may actually increase the rate of change in aortic pressure and, at least theoretically, exacerbate the dissection process. Alternatively, one of the newer antihypertensive agents such as nicardipine, Cleviprex (clevidipine butyrate), or fenoldopam may be considered. Initial medical monitoring and management should take place in an ICU in most cases, because a rapid and significant reduction in blood pressure and heart rate is the hallmark of optimal care. Blood pressure monitoring with an automatic blood pressure cuff apparatus may be sufficient if severe hypertension is not evident, the patient remains hemodynamically stable, and only a low dose of medication is required to control changes in aortic pressure. If the blood pressure and heart rate cannot be rapidly controlled, or if the patient does not rapidly become pain free, becomes hemodynamically unstable, or develops symptoms of associated malperfusion, an arterial monitoring line is mandatory, and early reimaging of the aorta should be considered. If the patient remains stable and pain free, he or she may be monitored outside the ICU after 24 to 48 hours. An imaging study (usually CTA scan or MRI) should be obtained before discharge as a baseline study.

Because surgical management of type B dissections is associated with very high mortality and morbidity, and because the results of with medical management are superior than to urgent surgical intervention, a nonoperative approach is taken in the vast majority of cases. Surgery through a lateral left thoracotomy is indicated for complications related to malperfusion or for chronic, severe pain indicative of dilatation, impending rupture, or progressive dissection. However, most of the complications related to malperfusion can be treated with catheter-based fenestration procedures or stent grafting,59 and these patients do not require surgical therapy. Stenting of the thoracic aorta is currently well established for treatment of complications of type B dissections, but its routine use is generally not recommended.60 Continued pain, new neurologic findings, and malperfusion syndromes not correctable with catheter-based fenestration or stent grafting may require surgical intervention. Cardiopulmonary bypass is generally used in surgical cases, cannulating the femoral artery and left atrium or both the femoral artery and vein. Cardiopulmonary bypass is usually instituted using total bypass, with or without profound hypothermic circulatory arrest. Alternatively, partial cardiopulmonary bypass (or isolated left heart bypass) can be used, depending on the surgeon’s preference. Although in theory, the use of cardiopulmonary bypass should lessen the incidence of postoperative paraplegia, the results of descending aortic surgery using total or partial cardiopulmonary bypass (or isolated left heart bypass) or a non-cardiopulmonary bypass approach are similar in most series.

Key Points

Daily PO, Trueblood HW, Stinson EB, et al. Management of acute aortic dissections. Ann Thorac Surg. 1970;10:237-247.

David TE, Feindel CM. An aortic valve-sparing operation for patients with aortic incompetence and aneurysm of the ascending aorta. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1992;103:617-621.

Gillinov AM, Lytle BW, Kaplon RJ, et al. Dissection of the ascending aorta after previous cardiac surgery: differences in presentation and management. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;117:252-260.

Miller DC. Surgical management of aortic dissections: indications, perioperative management, and long-term results. In: Doroghazi RM, Slater EE, editors. Aortic dissection. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1983:193-243.

Yacoub MH, Gehle P, Chandrasekaran V, et al. Late results of a valve-preserving operation in patients with aneurysms of the ascending aorta and root. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;115:1080-1090.

Coady MA, Ikonomidis JS, Cheung AT, et al. Surgical management of descending thoracic aortic disease: open and endovascular approaches. Circulation. 2010;121:2780-2804.

1 Leonard JC. Thomas Bevill Peacock and the early history of dissecting aneurysm. BMJ. 1979;2:260-262.

2 Maunoir JP. Memoires physiologiques et pratiques sur l’aneurysme et la ligature des arteres. Geneva: JJ Paschoud; 1802.

3 Paullin JE, James DF. Dissecting aneurysm of aorta. Postgrad Med. 1948;4:291.

4 Abbott OA. Clinical experiences with application of polythene cellophane upon aneurysms of thoracic vessels. J Thorac Surg. 1949;18:435.

5 DeBakey ME, Cooley D, Creech OJr. Surgical considerations of dissecting aneurysm of the aorta. Ann Surg. 1955;142:586-612.

6 DeBakey ME, Henry WS, Cooley DA, et al. Surgical management of dissecting aneurysms of the aorta. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1965;49:130-149.

7 Daily PO, Trueblood HW, Stinson EB, et al. Management of acute aortic dissections. Ann Thorac Surg. 1970;10:237-247.

8 Karthikesalingam A, Holt PJ, Hinchliffe RJ, et al. The diagnosis and management of aortic dissection. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;44(3):165-169.

9 Evangelista A, Eagle KA. Is the optimal management of acute type A aortic intramural hematoma evolving? Circulation. 2009;120(21):2029-2032.

10 Sundt TM. Intramural hematoma and penetrating aortic ulcer. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2007;22(6):504-509.

11 Sundt TM. Intramural hematoma and penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer of the aorta. Ann Thorac Surg. 83(2), 2007. S835-S831

12 Coady MA, Rizzo JA, Hammond GL, et al. Penetrating ulcer of the thoracic aorta: What is it? How do we recognize it? How do we manage it? J Vasc Surg. 1998;27:1006-1016.

13 Ganaha F, Miller DC, Sugimoto K, et al. Prognosis of aortic intramural hematoma with and without penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer: A clinical and radiologic analysis. Circulation. 2002;106:342-348.

14 Hirst AE, Johns VJ, Krime SJ. Dissecting aneurysm of the aorta: A review of 505 cases. Medicine. 1958;37:217-279.

15 Pate JW, Richardson RL, Eastridge CE. Acute aortic dissections. Am Surg. 1976;42:395-404.

16 DeSanctis RW, Doroghazi RM, Austen WG, et al. Aortic dissection. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1060-1067.

17 Fann JI, Miller DC. Aortic dissection. Ann Vasc Surg. 1995;9:311-323.

18 Fann JI, Smith JA, Miller DC, et al. Surgical management of aortic dissection during a 30-year period. Circulation. 1995;92(Suppl II):II113-II121.

19 Tsai TT, Trimarchi S, Nienaber CA. Acute aortic dissection: perspectives from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;37(2):149-159.

20 Cooper DG, Walsh SR, Sadat U, et al. Treating the thoracic aorta in Marfan syndrome: surgery or TEVAR? J Endovasc Ther. 2009;16(1):60-70.

21 Gillinov AM, Lytle BW, Kaplon RJ, et al. Dissection of the ascending aorta after previous cardiac surgery: Differences in presentation and management. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;117:252-260.

22 Eagle KA, Isselbacher EM, DeSanctis RW. Cocaine-related aortic dissection in perspective. Circulation. 2002;105:1529-1530.

23 Daniel JC, Huynh TT, Zhou W, et al. Acute aortic dissection associated with use of cocaine. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46(3):427-433.

24 Cambria RP, Brewster DC, Gertler J, et al. Vascular complications associated with spontaneous aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg. 1988;7:199-202.

25 Giugliano G, Spadera L, DeLaurentis M, et al. Chronic aortic dissection: still a challenge. Acta Cardiol. 2009;64(5):653-663.

26 Fann JI, Sarris GE, Mitchell RS, et al. Treatment of patients with aortic dissection presenting with peripheral vascular complications. Ann Surg. 1990;212:705-713.

27 Cigarroa JE, Isselbacher EM, DeSanctis RW, et al. Diagnostic imaging in the evaluation of suspected aortic dissection. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:35-43.

28 Meredith EL, Masani ND. Echocardiography in the emergency assessment of acute aortic syndromes. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009;10(1):i31-i39.

29 Moore AG, Eagle KA, Bruckman D, et al. Choice of computed tomography, transesophageal echocardiography, magnetic resonance imaging, and aortography in acute aortic dissection: International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD). Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:1235-1238.

30 Nienaber CA, von Kodolitsch Y, Petersen B, et al. The diagnosis of thoracic aortic dissection by noninvasive imaging procedures. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1-9.

31 Sommer T, Fehske W, Holzknecht N, et al. Aortic dissection: A comparative study of diagnosis with spiral CT, multiplanar transesophageal echocardiography and MR imaging. Radiology. 1996;199:347-352.

32 Urban BA, Bleumke DA, Johnson KM, et al. Imaging of thoracic aortic disease. Cardiol Clin. 1999;17:659-682.

33 DeBakey ME, McCollum CH, Crawford ES, et al. Dissection and dissecting aneurysms of the aorta: Twenty-year follow-up of five hundred and twenty-seven patients treated surgically. Surgery. 1982;92:1118-1134.

34 Haverich A, Miller DC, Scott WC, et al. Acute and chronic aortic dissections—determinants of long-term outcome for operative survivors. Circulation. 1985;72(Suppl II):II22-II34.

35 Gallo A, Davies RR, Coe MP. Indications, timing, and prognosis of operative repair of aortic dissections. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;17(3):224-235.

36 Fann JI, Sarris GE, Miller DC, et al. Surgical management of acute aortic dissection complicated by a stroke. Circulation. 1989;80(Suppl I):I257-I263.

37 Mohr-Lahaly S, Erbel R, Kearney P, et al. Aortic intramural hemorrhage visualized by transesophageal echocardiography: Findings and prognostic implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:658-664.

38 Kaji S, Akasaka T, Horibata Y, et al. Long-term prognosis of patients with type A aortic intramural hematoma. Circulation. 2002;106(Suppl I):I248-I252.

39 Moizumi Y, Komatsu T, Motoyoshi N, et al. Management of patients with intramural hematoma involving the ascending aorta. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;124:918-924.

40 Song JK, Kim HS, Somg JM, et al. Outcomes of medically treated patients with aortic intramural hematoma. Am J Med. 2002;113:181-187.

41 Fann JI, Glower DD, Miller DC, et al. Preservation of the aortic valve in patients with type A aortic dissection complicated by aortic valvular regurgitation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;102:62-75.

42 David TE, Feindel CM. An aortic valve-sparing operation for patients with aortic incompetence and aneurysm of the ascending aorta. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1992;103:617-621.

43 Kerendi F, Guyton RA, Vega JD, Kilgo PD, Chen EP. Early results of valve-sparing aortic root replacement in high-risk clinical scenarios. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89(2):471-476.

44 Yacoub MH, Gehle P, Chandrasekaran V, et al. Late results of a valve-preserving operation in patients with aneurysms of the ascending aorta and root. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;115:1080-1090.

45 Elefteriades JA. How I do it: Utilization of high-pressure sealants in aortic reconstruction. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;26(4):27.

46 Coady MA, Gleason TG. Type A aortic dissection. In: Sellke F, Ruel M, editors. Atlas of cardiac surgical techniques. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2009.

47 Yun KL, Glower DD, Miller DC, et al. Aortic dissection resulting from tear of transverse arch: Is concomitant arch repair warranted? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;102:355-368.

48 Crawford ES, Kirklin JW, Naftel DC, et al. Surgery for acute dissection of ascending aorta: Should the arch be included? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1992;104:46-59.

49 Lansman SL, Raissi S, Ergin MA, et al. Urgent operation for acute transverse aortic arch dissection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1989;97:334-341.

50 Van Arsdell GS, David TE, Butany J. Autopsies in acute type A aortic dissection: Surgical implications. Circulation. 1998;98(Suppl II):II299-II302.

51 Coady MA, Rizzo JA, Hammond GL, et al. What is the appropriate size criterion for resection of thoracic aorta aneurysms? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;113(3):476-491.

52 Shrestha M, Khaladj N, Hagl C, et al. Valve-sparing aortic root stabilization in acute type A aortic dissection. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2009;17(1):22-24.

53 Scholl FG, Coady MA, Davies RR, et al. Interval or permanent non-operative management of acute type A aortic dissection. Arch Surg. 134(4), 1999. 402-206

54 Kazui T, Washiyama N, Bashar AHM, et al. Surgical outcome of acute type A aortic dissection: Analysis of risk factors. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:75-82.

55 Kouchoukos NT, Wareing TH, Murphy SF, et al. Sixteen-year experience with aortic root replacement: Results of 172 operations. Ann Surg. 1991;214:308-318.

56 Mehta RH, Suzuki T, Hagan PG, et al. Predicting death in patients with acute type A aortic dissection. Circulation. 2002;105:200-206.

57 Sabik JF, Lytle BW, Blackstone EH, et al. Long-term effectiveness of operations for ascending aortic dissections. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;119:946-962.

58 Moon MR. Approach to the treatment of aortic dissection. Surg Clin North Am. 2009;89(4):869-893.

59 Dake MD, Kato N, Mitchell RS, et al. Endovascular stentgraft placement for the treatment of acute aortic dissection. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1546-1552.

60 Coady MA, Ikonomidis JS, Cheung AT, et al. Surgical management of descending thoracic aortic disease: open and endovascular approaches. Circulation. 2010;121:2780-2804.