Anxiety Disorders

Perspective

Acute anxiety and apprehension are common in emergency department (ED) patients. However, many medical conditions mimic anxiety disorders, and up to 42% of patients initially thought to have anxiety disorders are later found to have organic disease. Therefore, emergency physicians should thoroughly assess the anxious patient to identify and distinguish any underlying medical conditions and then appropriately treat that which is determined.1

Anxiety is a specific unpleasurable state of tension that forewarns the presence of danger, real or imagined, known or unrecognized, and is often verbalized as an intense feeling of worry. Vigilance is a positive consequence of anxiety that helps people to be alert to imminent danger. This awareness produces a greater ability to experience and manage extreme agitation.1

Up to a point, anxiety can improve performance with well-described adrenergic responses to stress that contribute to survival. However, when these responses go beyond a manageable point, further increases in anxiety add to the stress of the patient and lead to deterioration of performance and nonadaptive responses, resulting in pathologic anxiety (anxiety disorder). For instance, the threshold for pain may decrease, or the person may become more aware of body discomfort, with respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and neuromuscular complaints becoming prominent.1

Epidemiology

Approximately 40 million Americans older than 18 years, nearly 20% of adults, are affected by anxiety disorders each year.2 Anxiety disorders are among the most prevalent psychiatric disorders and are the most common psychiatric problems seen by primary care physicians, with 20% of these patients experiencing a type of anxiety disorder.3 Many primary care patients have significant mood and anxiety symptoms, such as panic disorders, generalized anxiety disorders, and depression, but nearly half of these symptomatic patients never receive appropriate treatment.4 Many patients would rather present with a physical complaint and try to disguise their anxiety than bear the perceived stigma associated with psychiatric complaints.5 Patients with chronic illness and those who make frequent medical visits have higher rates of anxiety and depression. The prevalence of anxiety disorders surpasses that of any other mental health disorder, including substance abuse. There is a close relationship between alcohol abuse and anxiety disorders; those with anxiety disorders often turn to alcohol and substance abuse as a form of self-medication, and the substance abuser frequently has underlying anxiety in relation to the use of alcohol and drugs.6

Principles of Disease

The precise mechanisms underlying the development of anxiety have not been fully established. Noradrenergic, serotonergic, and other neurotransmitter systems all play a role in the body’s response to stress. The serotonin system and the noradrenergic systems are common pathways implicated in anxiety. It is believed that low serotonin system activity and elevated noradrenergic system activity are involved, and thus selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) have become a focus of treatment. The well-established effectiveness of benzodiazepines in the treatment of anxiety has led to the study of the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) system and its relationship to anxiety. GABA is the principal inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, and benzodiazepines act on the GABAA receptors. Studies have focused on the role that corticosteroids may play in fear and anxiety. Steroids are thought to induce chemical changes in select neurons that strengthen or weaken certain neural pathways to affect behavior under stress.7

Anxiety reactions are also associated with aberrant metabolic changes induced by lactate infusion and hypersensitivity of the brainstem to carbon dioxide receptors. Studies focus on the regulatory centers found in the cerebral hemispheres. The hippocampus and the amygdala regulate emotion and memory and are important areas mediating an individual’s response to fear.8 Family research suggests genetic factors in anxiety, but the precise nature of the inherited vulnerability is unknown. Psychological and environmental factors, as outlined in psychodynamic, behavioral, and cognitive theories, also contribute in the generation of anxiety in biologically predisposed individuals.8

Clinical Features

The physical symptoms of autonomic arousal (e.g., tachypnea, tachycardia, diaphoresis, lightheadedness) may be the only manifestation of anxiety (Box 112-1). Patients may complain only of overall poor health or vague subjective findings when they visit the physician. Classic panic disorder symptoms of chest pain, shortness of breath, and the sense of impending doom will often lead the patient to the ED, especially if it is the very first episode.7 Anxiety associated with organic causes is more likely to be manifested with physical symptoms and less likely to be associated with avoidance behavior.9

Differential Considerations

Medical Illness Presenting as Anxiety

Patients with anxiety disorders may present with apparent physical disease, and many physical diseases may be strongly associated with symptoms of anxiety. Somatic symptoms can be so prominent that they occupy most of the patient’s attention, making it difficult to differentiate between a primary anxiety disorder and reactive anxiety to a situation or disease. Several factors help distinguish an organic anxiety syndrome from a primary anxiety disorder10 (Box 112-2). Anxiety disorder classifications, in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), include anxiety caused by a general medical condition11 (Box 112-3).

Anxious patients are frequently convinced that their problem is purely physical. The emergency physician should realize that the patient with anxiety is not in control of the symptoms and frequently cannot immediately identify the correct precipitant. Even though the patient may be uncomfortable, uncooperative, impatient, and unreasonable, triage medical personnel should recognize that the patient believes an illness truly exists and is not being consciously manipulative. Because anxiety may be the most obvious symptom of an underlying disease or condition, the patient should be evaluated for exacerbation of known preexisting disease as well as for onset of new illness since anxiety increases the risk of acute medical exacerbation of chronic illness.12

The classic scenarios of pulmonary embolism and hyperthyroidism causing anxiety are well documented. Cardiac disease studies indicate poorer outcomes in post–myocardial infarction patients with anxiety than in those without documented anxiety. Patients with respiratory diseases, such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, often have anxiety with their long-standing illnesses. In addition, many of the medications used to treat these illnesses may induce anxiety.5 The most common organic cause of anxiety is alcohol and drug use from either intoxication or, more typically, withdrawal states.

Cardiac Diseases

Various psychiatric conditions may be manifested with complaints of chest pain. Approximately 25% of patients with chest pain who present to the ED have panic disorder. Their disorder often goes undiagnosed, resulting in multiple visits and expensive cardiac evaluations.13 Some of the symptoms of myocardial infarction and angina pectoris may include crushing chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea, palpitations, heavy perspiration, and a feeling of impending death. These are also the primary symptoms of acute anxiety, but the pain is usually described as atypical, and patients are generally female and younger.14 Because of the morbidity and mortality of cardiovascular disease, a patient warrants a full cardiac evaluation when the differentiation between myocardial infarction and acute anxiety is unclear.

Cardiac dysrhythmias can cause palpitations, discomfort, dizziness, respiratory distress, and fainting. An anxious patient with a panic disorder will frequently have similar symptoms. Fortunately, most dysrhythmias can be documented and characterized on cardiac monitors or by electrocardiography. Mitral valve prolapse syndrome can be associated with palpitations and panic attacks indistinguishable from a panic disorder. Benzodiazepines can be used to provide symptomatic relief to patients who experience chest pain. Studies have shown that benzodiazepines reduce anxiety, pain, and cardiovascular activation. It is hypothesized that secondary to the reduction in circulating catecholamines, benzodiazepines may cause coronary vasodilation, prevent dysrhythmias, and block platelet aggregation.15

Endocrine Diseases

The DSM-IV defines the most common endocrinologic conditions associated with anxiety states as hypoparathyroidism, hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, hypoglycemia, pheochromocytoma, and hyperadrenocorticism.11 Anxiety is the predominant symptom in 20% of patients with hypoparathyroidism. Other symptoms include paresthesias, muscle cramps, muscle spasm, and tetany. Most cases are idiopathic or the result of surgical removal of the parathyroid glands during thyroidectomy. Studies indicate a higher incidence of anxiety in the subset of patients with surgically removed glands.16 The diagnosis of hypoparathyroidism is suggested by a low serum calcium level and a high phosphate level and confirmed by a parathyroid hormone assay.

Anxiety symptoms are seen in up to 40% of diabetics, and 14% of diabetic patients suffer from anxiety disorders. There is evidence that diabetics who are treated with antianxiety medication not only reduce their anxiety but also decrease their glycosylated hemoglobin levels and high-density lipoprotein concentration.17 Many patients with anxiety, somatoform, or characterologic disorders are convinced that they have reactive hypoglycemia. A normal result of a fingerstick blood glucose analysis done during an attack can exclude this diagnosis.

Pheochromocytomas are rare tumors that produce elevated levels of catecholamine in the body. Common symptoms include paroxysmal hypertension, headache, anxiety, sweating, flushing, abdominal and back pain, vomiting, and diarrhea. Pheochromocytoma attacks can be manifested just like panic attacks and can be precipitated by emotional stress. Whereas the sweating associated with pheochromocytoma attacks involves the whole body, the sweating in panic attacks is more likely to be confined to the hands, feet, and forehead. Elevated urinary catecholamine or plasma metanephrine levels can confirm a pheochromocytoma.18

Hyperthyroidism is one of the most frequently encountered endocrine diseases associated with anxiety. As with panic disorders, hyperthyroidism is associated with acute episodic anxiety. Thyrotoxicosis causes anxiety, palpitations, perspiration, hot skin, rapid pulse, active reflexes, diarrhea, weight loss, heat intolerance, proptosis, and lid lag.19 Psychiatric presentations can be the first sign of hypothyroidism, occurring as the initial symptom in 2 to 12% of reported cases along with organic mental deficits. Anxiety and progressive mental slowing associated with diminished recent memory and speech deficits with diminished learning ability are the characteristic initial progression of symptoms. The severity of anxiety disorders in hypothyroid states relates to the rapidity of thyroid hormone level changes more than to the absolute levels. In general, checking of the serum thyroid-stimulating hormone and free thyroxine levels will suffice in the ED to establish the diagnosis of thyroid disease.20

Respiratory Diseases

Most conditions causing airway compromise or impairing gas exchange would never be mistaken for a psychiatric disorder. However, in some conditions that cause hypoxemia or hypercarbia, patients may present with significant anxiety, and up to a third of the patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease meet the criteria for anxiety disorder.21

Asthma is characterized by episodic attacks of dyspnea and often anxiety. Anxiety can also precipitate and prolong asthma attacks. Patients who have severe asthma are twice as likely to have an anxiety disorder and almost five times as likely to have a phobia compared with nonasthmatics. Severe asthmatics are almost five times as likely to have a panic disorder and about four times as likely to have a panic attack. Acute dyspnea from pure panic attack with good air movement and normal lung sounds is easily differentiated from an asthma attack, but studies consistently show that anxiety disorders increase asthma morbidity and mortality.22

Shortness of breath is a common complaint in the ED. When it is accompanied by anxiety, panic attacks or anxiety disorders may be high on the differential diagnosis, but so is pulmonary embolism. Acute shortness of breath in any patient should never be dismissed lightly, especially because pulmonary embolus can be manifested with only shortness of breath as the major symptom. The emergency physician can distinguish these patients by paying close attention to history and examination, assessing risk factors for thromboembolic disease, and using basic investigations (e.g., pulse oximetry, electrocardiography, chest radiography, and D-dimer assay) and further tests as indicated.23

Neurologic Disorders

Many neurologic conditions are associated with anxiety symptoms.24–26 Temporal lobe seizures, complex partial seizures, tumors, arteriovenous malformation, and ischemia or infarction have been reported with panic attacks. Anxiety often accompanies a transient ischemic attack and may be the major symptom on presentation if the episode has resolved by the time the patient reaches the ED. The coexistence of anxiety disorders plays an important role in the prognosis and impairment of patients who have had cerebral vascular accidents with neurologic sequelae. Anxiety and depression are associated with left-hemispheric strokes, and anxiety alone is associated with right-hemispheric strokes. Finally, anxiety disorders occur in the aftermath of traumatic brain injury.27 In Huntington’s disease, anxiety is the most common prodromal symptom. Anxiety occurs in up to 40% of patients with Parkinson’s disease and up to 37% of patients with multiple sclerosis. Similarly, anxiety symptoms are common in moderate Alzheimer’s disease.

Drug Intoxication and Withdrawal States

Amphetamines, cocaine, and sympathomimetic drugs are abused for their stimulant and mind-altering properties. Patients often present to the ED agitated, anxious, or aggressive when these drugs are taken in large doses and with prolonged use. Caffeine is a common stimulant. Energy drinks and gourmet coffee represent a rapidly growing market in the United States. These drinks are packed with caffeine and the herbal equivalent guarana as well as Ginkgo biloba. Studies suggest that 240 to 300 mg of caffeine per day should be the upper limit of healthy consumption. Many energy drinks contain that amount in a single serving.25 Although lower doses of caffeine can be pleasantly stimulating, higher doses may cause hyperalertness, hypervigilance, motor tension, tremors, gastrointestinal distress, and anxiety. The acute symptoms of caffeine intoxication and generalized anxiety disorder are almost identical. Stimulants such as ephedra and ephedrine-based compounds are found in many dietary supplements and listed by the herbal name of ma huang. Despite the Food and Drug Administration ban on ephedra-containing compounds in 2004, access to these drugs still exists over the Internet.

Many illicit drug users who use marijuana believe that the drug reduces their anxiety, but some experience a depersonalization that provokes severe anxiety, fearfulness, and agoraphobic symptoms. Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), phencyclidine (PCP), and ecstasy are hallucinogens that can produce anxiety and paranoia from chronic use or “bad trips.” Flashbacks affect some users of LSD; the person may experience the symptoms of anxiety and paranoia weeks or months after use.26

Benzodiazepine withdrawal is rarely fatal but can be very unpleasant. In anxious patients, severe rebound anxiety can occur after a few weeks’ use of recommended therapeutic doses. Lorazepam and alprazolam are short-acting agents, and their abrupt discontinuation frequently causes panic attacks within 1 to 2 days. With longer-acting agents, withdrawal symptoms typically peak in about 1 week. Some people may experience this rebound as stimulating. Although antidepressants are rarely abused, their abrupt withdrawal can also cause an abstinence syndrome of insomnia, vivid nightmares, and extreme anxiety.27

Alcohol withdrawal, in alcohol-dependent individuals or heavy binge drinkers, can appear 6 to 12 hours after the last drink or significant reduction in consumption of alcohol. Patients often have detectable alcohol still in their systems at this time. Anxiety is one of the first and most prominent symptoms and is seen within 24 to 48 hours of the withdrawal state.28

Anxiety in Primary Psychiatric Disorders

Even in patients with known psychiatric illness, a panic disorder is a diagnosis of exclusion because several mental illnesses cause panic attacks as a secondary manifestation. The presence of panic often influences the treatment and outcome of the primary illness. Panic attacks can occur as part of a bipolar (manic-depressive) disorder, in either the manic or the depressed phase. In manic and hypomanic disorders, the patient’s predominant affect is usually cheerful and euphoric but may also be dysphoric with irritability and extreme anxiety of panic proportions.29

Early in the course of schizophrenia, a patient will often experience panic attacks. Fearfulness, tension, agitation, immobility, disorganized thinking, dilated pupils, extreme insecurity, suspiciousness, and delusions of reference and persecution may characterize schizophrenic panic attacks. The hallucinations often have derogatory accusative content. Social anxiety is a common and disabling condition with schizophrenia that is unrelated to clinical psychotic symptoms.30

Patients with somatoform disorders report a variety of somatic symptoms, including panic attacks, and 68% report a history of anxiety. Patients claim to have most of the physical symptoms they are asked about, even when evidence excluding illness is presented to the patient. Fear and anxiety initiate, facilitate, and maintain many of the symptoms encountered in the somatoform patient. Patients with “pure” anxiety disorders tend to be hypochondriacal, whereas those with somatization are more likely to improve transiently with active medication or placebo but rarely respond so well that they stop seeking unnecessary medical attention. Patients with panic disorders, however, seek at least as much psychiatric attention as do those with somatoform disorders.31

Approximately 50% of patients with a primary panic disorder major depression and many others are bothered by some degree of depression in mood. Twenty percent of patients with depression have panic attacks, and the remainder have considerable anxiety. Depression with panic attacks responds less well to treatment. Agitated depression with anxiety and psychosis, sometimes called involutional melancholia, responds well to electroconvulsive therapy. Depression with anxiety and hostility responds well to antidepressants, but benzodiazepines can exacerbate symptoms.32

Post-traumatic stress disorder is characterized by the re-experiencing of an extremely traumatic event. The symptoms are closely related to and worsened by reminders of the trauma. The flashbacks, in which patients reexperience the original trauma, can have the same symptoms as panic attacks. These patients often avoid crowds or social situations.33

A phobia is an irrational fear that results in avoidance. It is considered normal in children because the objects of fear tend to be things that seem dangerous to a child (e.g., spiders, snakes, enclosed places, the dark). Phobia becomes a disorder when it interferes with day-to-day function in an individual’s life. A social phobia is characterized by clinically significant anxiety provoked by exposure to a specific feared object or situation, often leading to avoidance behavior. Social phobias prevent a patient from doing such activities as public speaking, performing, visiting, using public showers or restrooms, or eating in public places. Agoraphobia is a fear of being alone in public places. Nearly 75% of agoraphobic patients have panic attacks.34 Those with panic attacks are more likely to seek treatment, whereas those with uncomplicated agoraphobia tend to stay at home. Agoraphobia without panic attacks may not differ fundamentally from other simple phobias. Most panic disorder patients have multiple phobias, including agoraphobia, which is believed to result from the panic patient’s increasing attempts to avoid places or situations in which the panic attacks would be particularly inconvenient or difficult to control. Agoraphobic patients particularly avoid places from which escape would be difficult (e.g., bridges, crowded theaters). When they do attend theaters, they favor seats on the aisle and near the door. Panic attacks in agoraphobic patients are more likely to include fear of losing control, whereas those not associated with agoraphobia are more likely to include dyspnea and dizziness.35

An obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is characterized by recurrent, obtrusive, unwanted thoughts (obsessions), such as fears of contamination, and compulsive behaviors or rituals (compulsions), such as handwashing or checking. OCD is classified as an anxiety disorder because (1) anxiety or tension is often associated with obsessions and resistance to compulsions, (2) anxiety or tension is often immediately relieved by yielding to compulsions, and (3) OCD often occurs in association with other anxiety disorders. In summary, the obsessions and intrusive thoughts increase anxiety and the compulsions and repetitive behaviors decrease anxiety but with significant disruption of one’s life.9

Management

The patient should first be placed in a quiet area for evaluation. Some patients calm down when they are removed from the chaotic ED environment. If the emergency physician encounters difficulty in calming the patient, supportive family members may help. A known and trusted face often helps anxious patients make order out of their inner turmoil. Prior discussion and clarification with the family are essential to elicit their support.1

Once the patient is calmed, a more formal evaluation can begin. The emergency physician should ask open-ended questions and observe the patient’s responses carefully. Questions about drug or alcohol use should be delayed until rapport has been established. Reassurance should not be premature; this important interventional technique is more effective when it is delayed until after the patient’s specific concerns are clarified.1

If a somatic concern is the major component of the acute anxiety attack, a physical examination with particular attention to the area of complaint is important, even when there is overwhelming evidence of a functional etiology to the patient’s complaints. Anxiety attacks are stressful experiences in themselves and can cause deterioration in marginally compensated organ systems. Careful evaluation reassures the patient and avoids the problem of a premature “medical clearance.” Abnormal vital signs should suggest an organic cause of the anxiety symptoms.9

Because of the physical nature of the symptoms, patients with anxiety and panic attacks often seek treatment in the ED rather than in a psychiatric setting. A calm manner and willingness to listen usually relieve some of the patient’s initial anxiety. An anxiety or panic reaction may be precipitated by the loss of a significant relationship, a job, a living situation, or self-esteem as well as by physical illness or injury. Once the patient describes a trigger event, the emergency physician should restate it, as if experiencing a similar situation. This gives the patient authoritative approval to express embarrassing feelings. A patient who has frequent anxiety reactions is usually suggestible and will respond to reassurance. Conversely, an anxious or unsympathetic physician will only compound the problem.1

Anxiety is common in the geriatric population; prevalence rates are conservatively estimated at 10%, with higher rates in patients with chronic illness. Anxiety disorders may be the most common psychiatric ailments experienced by elders, but this age group is the least studied of all patients.36 Older patients with anxiety often have somatic complaints. They require a careful investigation for underlying medical illness, other psychiatric conditions, and use of over-the-counter and prescription drugs.

Pharmacologic Treatment

In the past few years, emergency physicians and the public have become increasingly concerned about the growing use of benzodiazepines in the United States. More than 1 million Americans are physically dependent on sedatives. When sedatives are given in place of understanding, support, and intrapersonal therapies, patients are taught to rely on the external support of a pill rather than on inner resources.8

Benzodiazepines can be prescribed for motivated patients with acute exogenous anxiety for time-limited stress. Patients who are cooperative, employed, educated, married, and aware that their symptoms have a psychological basis are more likely to respond. Benzodiazepines are an attractive alternative to the delayed response of an SSRI when an immediate reduction of symptoms is desired or a short-term treatment is needed. Benzodiazepines can be given in one or two daily doses to make use of their short half-lives; alternatively, a bedtime dose may minimize daytime sedation and still manifest a daytime anxiolytic effect. Benzodiazepines should not be prescribed for more than a week. Patients who do not improve within a week are unlikely to benefit from the drug. Patients with a history of alcoholism or drug abuse, who are excessively and emotionally dependent, or who become anxious in response to normal stress are at greater risk of drug dependency and are not good candidates for this treatment from an emergency physician. Dependence and abstinence syndromes have been reported to occur with low doses of sedating drugs, especially if they are taken for more than 8 months. Short-acting benzodiazepines (e.g., lorazepam, oxazepam) should be prescribed at low dosages for patients with liver disease or organic brain syndrome and for those taking medications that either depress central nervous system function or inhibit benzodiazepine metabolism and clearance. Withdrawal rebound symptoms are more common with discontinuation of benzodiazepines than with other antianxiety treatments. Short-acting benzodiazepines produce a more severe abstinence syndrome when they are stopped abruptly, and thus many physicians prefer the longer-acting benzodiazepines.7 For some patients, switching from a short-acting agent (e.g., alprazolam) to a long-acting agent (e.g., clonazepam) can be helpful before initiation of a taper.

Buspirone is a nonbenzodiazepine used in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Buspirone does not appear to cause dependency; it is less sedating than benzodiazepines, and tolerance does not occur at therapeutic doses. It is the therapeutic lag in efficacy of 2 to 3 weeks that has limited the use of buspirone. It has had variable and sometimes disappointing results in clinical practice, particularly when it is used in patients with prior exposure to benzodiazepines.36

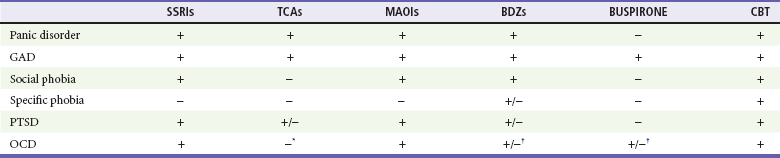

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are effective for panic disorders and generalized anxiety disorders but are ineffective for social phobias and, with the exception of clomipramine, are largely ineffective for OCD as well. TCAs have been used effectively for depressive and anxiety symptoms associated with post-traumatic stress disorder. TCAs include imipramine, nortriptyline, desipramine, amitriptyline, and doxepin. The TCAs have been supplanted by the SSRIs and SNRIs as first-line interventions for the treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders.37

Patients with endogenous anxiety (panic attacks with or without agoraphobia) should be referred to a psychiatrist to establish a good therapeutic relationship before using anxiolytic medication. Benzodiazepines, tricyclics, SSRIs, SNRIs, and MAOIs are safe and effective in endogenously anxious patients who are under psychiatric care (Table 112-1). Recurrence rates of panic attacks are high when drug therapy is discontinued.8

Nonpharmacologic Therapy

Psychotherapies may be helpful for individuals whose psychological makeup, coping style, interpersonal dynamics, and situational stressors contribute to their pathologic anxiety. The use of supportive, insight-oriented family therapy is helpful when these factors appear prominently in the patient’s presentation.8

Cognitive-behavioral therapy is predicated on the theory that the distress and impairment associated with anxiety and panic are mediated by maladaptive cognitive responses that promote anxiety and avoidance. The core components of cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder include correction of cognitive misperceptions and overreactions to anxiety symptoms, breathing retraining, and muscle relaxation as well as exposure and desensitization to phobic situations. Cognitive-behavioral therapy is very effective but requires commitment from the patient.8,9

Meditation (e.g., Zen, yoga, transcendental) has been proposed by many authorities, but few clinical data support its efficacy in anxiety disorders. Biofeedback appears promising for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Hypnotic suggestion may be effective because anxious patients tend to be cognitively scattered, unable to focus their attention, and highly suggestible. A hypnotic state can often be induced by specific stimuli.38

These nonpharmacologic techniques take anxious patients out of the future, about which they are frightened, and place them into the present. These techniques should be reinforced by the development of a physically and psychologically healthy lifestyle. A significant social support system not only protects against vulnerability to illness but also is highly anxiolytic. Regular exercise (e.g., dancing, swimming, bicycling, walking, jogging) also promotes tranquility. Encouragement of activity that focuses on hand-eye-ear coordination (e.g., painting, playing keyboard, needlework) helps anxious patients regain and maintain control by bringing them into the present.1

Disposition

1. Rule out organic illnesses as a cause of anxiety.

2. Evaluate for substance abuse and medications associated with anxiety.

3. Determine whether anxiety is endogenous (without outside trigger) or exogenous (after an outside trigger).

4. Clarify what is currently frightening the patient.

5. Evaluate the patient’s capacity for self-awareness.

6. Assess techniques that have worked in the past.

8. Give the patient as much control over the care plan as feasible.

9. Select patients to start with a short course of benzodiazepines, and educate patients about treatment.

10. Apply adjunctive techniques as appropriate for the patient’s personality and the physician’s preference (e.g., hypnotic suggestion, breathing exercises).

Patients with a panic disorder associated with suicidal or homicidal ideation or with severe depression require urgent psychiatric attention and admission to the hospital. Other patients with suspected endogenous or severe exogenous anxiety disorders should be referred for psychiatric evaluation. The Anxiety and Depression Association of America can be contacted (240-485-1001) for a national registry of clinicians and treatment programs specializing in anxiety disorders or can be found online at www.adaa.org.

References

1. Kercher, EE. Anxiety. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1991;9:161.

2. Kessler, RC, et al. Prevalence, severity and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617.

3. Kroenke, K, Spitzer, RL, Williams, JB, Monahan, PO, Löwe, B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:317.

4. Weisberg, R, et al. Psychiatric treatment in primary care patients with anxiety disorders: A comparison of care received from primary care providers and psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:276.

5. Rogers, MP, Wolfe, DJ. Anxiety in the medical patient. Psychiatric Times. 2007;24:29.

6. Grant, BF, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:807.

7. Hermida, T, Malone, D. Anxiety Disorders. www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/psychiatry/anxiety-disorder, 2004.

8. Hollander, E, Simeon, D, Gorman, JM. Anxiety disorders. In Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, Talbott JA, eds.: The American Psychiatric Press Textbook of Psychiatry, 3rd ed, Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1999.

9. Pollack, MH, Smoller, JW, Lee, DK. Approach to the anxious patient. In: Stern TA, Herman JB, Slavin PL, eds. Guide to Psychiatry in Primary Care. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998.

10. Rosenbaum, JF, et al. Anxiety. In Cassem NH, Stern TA, Rosenbaum JF, Jellinek MS, eds.: Massachusetts General Hospital Handbook of General Hospital Psychiatry, 4th ed, St Louis: Mosby, 1998.

11. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

12. Davies, SJ, et al. Association of panic disorder and panic attacks with hypertension. Am J Med. 1999;107:310.

13. Huffman, JC, Pollack, MH, Stern, TA. Panic disorder and chest pain: Mechanisms, morbidity, and management. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;4:54–62.

14. Huffman, JC, Pollack, MH. Predicting panic disorders among patients with chest pain: An analysis of the literature. Psychosomatics. 2003;44:222.

15. Huffman, JC, Stern, TA. The use of benzodiazepines in the treatment of chest pain: A review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2003;25:427.

16. Yudofsky, SC, Hales, RE. Neuropsychiatric aspects of endocrine disorders. In: Yudofsky SC, Hales RE, eds. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2002:868.

17. Grigsby, AB, et al. Prevalence of anxiety in adults with diabetes: A systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:1053.

18. Levenson, JL. Psychiatric issues in endocrinology. Prim Psychiatry. 2006;13:27.

19. Dement, MM, et al. Depression and anxiety in hyperthyroidism. Arch Med Res. 2002;33:552.

20. Ringel, MD. Management of hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Clin. 2001;17:59.

21. Brenes, G. Anxiety and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Prevalence, impact, and treatment. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:963.

22. Goodwin, RD, Jacobi, F, Thefeld, W. Mental disorders and asthma in the community. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1125.

23. Mehta, TA, Sutherland, JG, Hodgkinson, DW. Hyperventilation: Cause or effect? J Accid Emerg Med. 2000;17:376.

24. Stein, DJ, Hugo, FJ. Neuropsychiatric aspects of anxiety disorders. In Yudofsky SC, Hales RE, eds.: The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 4th ed, Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2002.

25. Berigan, T. An anxiety disorder secondary to energy drinks. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2005;2:10.

26. Salomone, JA, III., Hallucinogen toxicity. Emedicine, updated Apr 28: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/814848-overview, 2011.

27. Sola, CL, Sedative, hypnotic, anxiolytic use disorders. Emedicine, updated Jun 27. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/290585-overview, 2011.

28. McKeown, NJ, Withdrawal syndromes. Emedicine, updated June 4. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/819502-overview, 2012.

29. Sasson, Y, et al. Bipolar comorbidity: From diagnostic dilemmas to therapeutic challenge. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;6:139.

30. Tibbo, P, Swainson, J, Chue, P, LeMelledo, JM. Prevalence and relationship to delusion and hallucinations of anxiety disorders in schizophrenia. Depress Anxiety. 2003;17:65.

31. Oyama, O, Paltoo, C, Greengold, J. Somatoform disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:1333.

32. Zimmerman, M, Chelminski, I. Generalized anxiety disorder in patients with major depression: Is DSM-IV’s hierarchy correct? Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:504.

33. Howard, S, Hopwood, M. Post-traumatic stress disorder. A brief overview. Aust Fam Physician. 2003;32:683.

34. Preda, A, Phobic disorders. Emedicine, updated Mar 29. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/288016-overview, 2011.

35. Craske, MG, DeCola, JP, Sachs, AD, Pontillo, DC. Panic control treatment for agoraphobia. J Anxiety Disord. 2003;17:321.

36. Roerig, JL. Diagnosis and management of generalized anxiety disorder. J Am Pharmaceut Assoc. 1999;39:811.

37. Schatzberg, AF, Nemeroff, CB. Textbook of Psychopharmacology, 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004.

38. Spiegel, MD, Maldonado, JR. Hypnosis. In Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, Talbott JA, eds.: The American Psychiatric Press Textbook of Psychiatry, 3rd ed, Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1999.