Chapter 23 Anxiety Disorders

Preschoolers typically have specific fears related to the dark, animals, and imaginary situations, in addition to normative separation anxiety. Preoccupation with orderliness and routines (just right phenomena) often takes on a quality of anxiety for preschool children. Parents’ reassurance is usually sufficient to help the child through this period. Although most school-aged children abandon the imaginary fears of early childhood, some replace them with fears of bodily harm or other worries (Table 23-1). In adolescence, general worrying about school performance and worrying about social competence are common and remit as the teen matures.

Table 23-1 CRITERIA FOR DIAGNOSIS OF SPECIFIC PHOBIA

SPECIFY TYPE:

From Kliegman RM, Marcdante KJ, Jenson HB, et al, editors: Nelson essentials of pediatrics, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2006, Elsevier/Saunders, p 92.

Genetic or temperamental factors contribute more to the development of some anxiety disorders, whereas environmental factors are closely linked to the cause of others. Specifically, behavioral inhibition appears to be a heritable tendency and is linked with social phobia, generalized anxiety, and selective mutism. OCD and other disorders associated with OCD-like behaviors, such as Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders, tend to have high genetic risk as well (Chapter 590.4). Environmental factors, such as parent-infant attachment and exposure to trauma, contribute more to SAD and PTSD. Parental anxiety disorder is associated with an increased risk of anxiety disorder in offspring. Differences in the size of the amygdala and hippocampus are noted in patients with anxiety symptoms.

When a child reports recurring acute severe anxiety, antidepressant or anxiolytic medication is often necessary. Controlled studies of tricyclic antidepressants (imipramine) and benzodiazepines (clonazepam) show that these agents are not generally effective. Data support the use of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (see Table 19-4). One controlled trial of 488 children, 7-17 yr, which included children with a primary diagnosis of SAD, compared 12 wk of treatment with CBT, the SSRI, sertraline, their combination, and placebo. Nearly 81% of those treated with combination therapy improved, 55% for SSRI alone, 60% for CBT. All treatments were superior to placebo (24% response rate). The SSRI was well tolerated and had few side effects; adverse events, including suicidal and homicidal ideation, did not differ between the SSRI and placebo groups. There was no attempted suicide among the 488 children. CBT was associated with less insomnia, fatigue, sedation, and restlessness than SSRI. Combining SSRI with CBT may be the best approach to achieving a positive response; long-term SSRI treatment can provide additional benefit.

Childhood-onset social phobia (social anxiety disorder) is characterized by excessive anxiety in social settings (including the presence of unfamiliar peers, or unfamiliar adults) or performance situations, leading to social isolation (Table 23-2) and is associated with social scrutiny and fear of doing something embarrassing. Fear of social settings can also occur in other disorders, such as GAD. Avoidance or escape from the situation usually dissipates anxiety in social phobia (SP), unlike GAD, where worry persists. Children and adolescents with SP often maintain the desire for involvement with family and familiar peers. When severe, the anxiety can manifest as a panic attack.

Table 23-2 CRITERIA FOR DIAGNOSIS OF SOCIAL PHOBIA

SPECIFY IF

Generalized: if the fears include most social situations (e.g., initiating or maintaining conversations, participating in small groups, dating, speaking to authority figures, attending parties). Note: Also consider the additional diagnosis of avoidant personality disorder

From Kliegman RM, Marcdante KJ, Jenson HB, et al, editors: Nelson essentials of pediatrics, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2006, Elsevier/Saunders, p 93.

Social effectiveness therapy for children (SET-C), alone or with SSRIs, is considered the treatment of choice for SP (see Table 19-4). SSRI and SET-C are superior to placebo in reducing social distress and behavioral avoidance and increasing general functioning. SET-C may be better than SSRI in reducing these symptoms. SET-C, but not SSRI, may be superior to placebo in improving social skills, decreasing anxiety in specific social interactions, and enhancing social competence. SSRIs have a maximum effect by 8 wk; SET-C provides continued improvement through 12 wk. A combination of SSRI and CBT is superior to either treatment alone in reducing severity of anxiety in children with SP and other anxiety disorders. β-Adrenergic blocking agents are used to treat SP, particularly the subtype with performance anxiety and stage fright. β-Blockers are not FDA approved for SP.

Selective mutism is conceptualized as a disorder that overlaps with SP. Children with selective mutism talk almost exclusively at home, although they are reticent in other settings, such as school, daycare, or even relatives’ homes. Often, one or more stressors, such as a new classroom or conflicts with parents or siblings, drive an already shy child to become reluctant to speak. It may be helpful to obtain history of normal language use in at least one situation to rule out any communication disorder, neurologic disorder, or pervasive developmental disorder as a cause of mutism. Fluoxetine in combination with behavioral therapy is effective for children whose school performance is severely limited by their symptoms (Chapter 32).

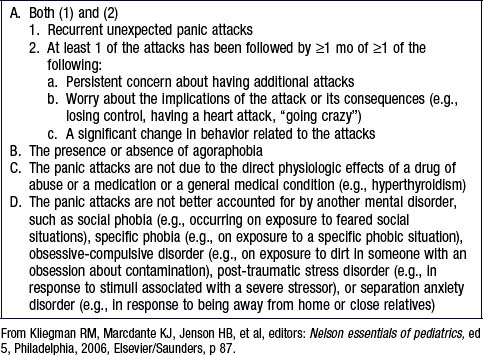

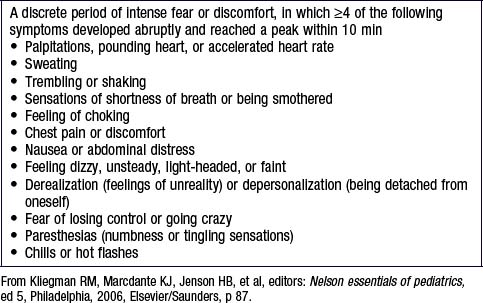

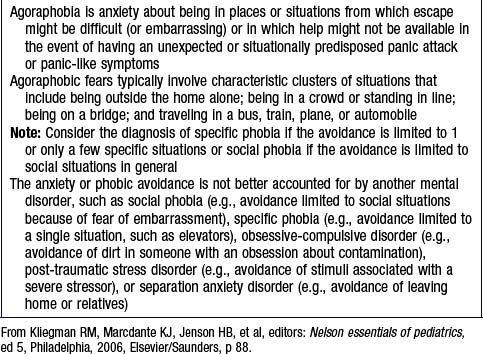

Panic disorder is a syndrome of recurrent, discrete episodes of marked fear or discomfort in which patients experience abrupt onset of physical and psychologic symptoms called panic attacks (Tables 23-3 and 23-4). Physical symptoms can include palpitations, sweating, shaking, shortness of breath, dizziness, chest pain, and nausea. Children can present with acute respiratory distress but without fever, wheezing, or stridor, ruling out organic causes of the distress. The associated psychologic symptoms include fear of death, impending doom, loss of control, persistent concerns about having future attacks, and avoidance of settings where attacks have occurred (agoraphobia: Table 23-5).

Table 23-3 CRITERIA FOR DIAGNOSIS OF PANIC DISORDER

Table 23-4 CRITERIA FOR DIAGNOSIS OF A PANIC ATTACK

Table 23-5 CRITERIA FOR DIAGNOSIS OF AGORAPHOBIA

SSRIs have shown effectiveness in the treatment of adolescents (see Table 19-4). CBT may also be helpful. The recovery rate is approximately 70%.

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) occurs in children who often experience unrealistic worries about different events or activities for at least 6 mo (Table 23-6) with at least one somatic complaint. The diffuse nature of the anxiety symptoms differentiates it from other anxiety disorders. Worries in children with GAD commonly center around concerns about competence and performance in school and athletics. GAD often manifests with somatic symptoms including restlessness, fatigue, problems concentrating, irritability, muscle tension, and sleep disturbance. Given the somatic symptoms characteristic of GAD, the differential diagnosis must consider other medical causes. Excessive use of caffeine or other stimulants in adolescence is common and should be determined with a careful history. When the history or physical exam is suggestive, the pediatrician should rule out hyperthyroidism, hypoglycemia, lupus, and pheochromocytoma.

Table 23-6 CRITERIA FOR DIAGNOSIS OF GENERALIZED ANXIETY DISORDER

From Kliegman RM, Marcdante KJ, Jenson HB, et al, editors: Nelson essentials of pediatrics, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2006, Elsevier/Saunders, p 89.

Children with GAD are good candidates for CBT, an SSRI, or their combination (see Table 19-4). Buspirone may be used as an adjunct to SSRI therapy. Combination of CBT and SSRI often results in a superior response in pediatric patients with anxiety disorders, including GAD. The recovery rate is approximately 80%.

It is important to distinguish children with GAD from those who present with specific repetitive thoughts that invade consciousness (obsessions) or repetitive rituals or movements that are driven by anxiety (compulsions). The most common obsessions are concerned with bodily wastes and secretions, the fear that something calamitous will happen, or the need for sameness. The most common compulsions are hand washing, continual checking of locks, and touching. At times of stress (bedtime, preparing for school), some children touch certain objects, say certain words, or wash their hands repeatedly. OCD is diagnosed when the thoughts or rituals cause distress, consume time, or interfere with occupational or social functioning (Table 23-7).

Table 23-7 CRITERIA FOR DIAGNOSIS OF OBSESSIVE-COMPULSIVE DISORDER

SPECIFY IF

With poor insight: if, for most of the time during the current episode, the person does not recognize that the obsessions and compulsions are excessive or unreasonable

From Kliegman RM, Marcdante KJ, Jenson HB, et al, editors: Nelson essentials of pediatrics, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2006, Elsevier/Saunders, p 98.

There are four FDA-approved medications for pediatric OCD: fluoxetine, sertraline, fluvoxamine, and clomipramine. Clomipramine, a heterocylic antidepressant and nonselective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, is only indicated when a patient has failed 2 or more SSRI trials. There may be a critical role for glutamate in the pathogenesis and treatment response of OCD. The glutamate inhibitor riluzole (Rilutek) is FDA-approved for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Chapter 604.3) and has a good safety record. The most common adverse event with riluzole is transient increase in liver transaminases. Riluzole in children with treatment-resistant OCD may be beneficial and is well tolerated. Referral of patients with OCD to a mental health professional is always indicated.

In 10% of children with OCD, symptoms are triggered or exacerbated by group A β-hemolytic streptococcal infection (GABHS) (Chapter 176). GABHS bacteria trigger antineuronal antibodies that cross react with basal ganglia neural tissue in genetically susceptible hosts, leading to swelling of this region and resultant obsessions and compulsions. This subtype of OCD, called pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infection (PANDAS), is characterized by sudden and dramatic onset or exacerbation of OCD or tic symptoms, associated neurologic findings, and a recent streptococcal infection. Increased antibody titers of antistreptolysin O and antideoxyribonuclease B correlates with increased basal ganglia volumes. Plasmapheresis is effective in reducing OCD symptoms in some patients with PANDAS and also decreasing enlarged basal ganglia volume. The pediatrician should be aware of the infectious cause of some cases of tic disorders, attention-deficit disorder, and OCD and follow management guidelines (Chapter 22).

Children with phobias avoid specific objects or situations that reliably trigger physiologic arousal (e.g., dogs or spiders) (see Table 23-1). The fear is excessive and unreasonable and can be cued by the presence or anticipation of the feared trigger, with anxiety symptoms occurring immediately. Neither obsessions nor compulsions are associated with the fear response; phobias only rarely interfere with social, educational, or interpersonal functioning. Assault by a relative and verbal aggression between parents can influence the onset of specific phobias. The parents of phobic children should remain calm in the face of the child’s anxiety or panic. Parents who become anxious themselves may reinforce their children’s anxiety, and the pediatrician can usefully interrupt this cycle by calmly noting that phobias are not unusual and rarely cause impairment. The prevalence of specific phobias in childhood is 0.5-2.0%.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; see Chapter 36) is typically precipitated by an extreme stressor. PTSD is an anxiety disorder resulting from the long- and short-term effects of trauma that cause behavioral and physiologic sequelae in toddlers, children, and adolescents (Table 23-8). Another diagnostic category, acute stress disorder, reflects the fact that traumatic events often cause acute symptoms that may or may not resolve. Previous trauma exposure, a history of other psychopathology, and symptoms of PTSD in parents predict childhood-onset PTSD. Many adolescent and adult psychopathologic conditions, such as conduct disorder, depression, and some personality disorders, might relate to previous trauma. PTSD is also linked to mood disorders and disruptive behavior. Separation anxiety is common in children with PTSD. The lifetime prevalence of PTSD by age 18 yr is approximately 6%. Up to 40% show symptoms, but do not fulfill the diagnostic criteria.

Table 23-8 CRITERIA FOR DIAGNOSIS OF POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

SPECIFY IF

SPECIFY IF

With delayed onset: if onset of symptoms is >6 mo after the stressor

From Kliegman RM, Marcdante KJ, Jenson HB, et al, editors: Nelson essentials of pediatrics, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2006, Elsevier/Saunders, p 90.

Initial interventions after a trauma should focus on reunification with a parent and attending to the child’s physical needs in a safe place. Aggressive treatment of pain might decrease the likelihood of PTSD, and facilitating a return to comforting routines, including regular sleep, is indicated. Long-term treatment may include individual, group, school-based, or family therapy, as well as pharmacotherapy, in selected cases. Individual treatment involves transforming the child’s concept of himself or herself as victim to that of survivor and can occur through play therapy, psychodynamic therapy, or CBT. Group work is also helpful for identifying which children might need more intensive assistance. Goals of family work include helping the child establish a sense of security, validating his or her emotions, and anticipating situations when the child will need more support from the family. Clonidine or guanfacine may be helpful for sleep disturbance, persistent arousal, and exaggerated startle response. Comorbid depression and affective numbing might respond to an SSRI (see Table 19-4). As for many other anxiety disorders, CBT is the psychotherapeutic intervention with the most empiric support.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

Beidel DC, Turner SM, Sallee FR, et al. SET-C versus fluoxetine in the treatment of childhood social phobia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:1622-1632.

Brezo J, Barker ED, Paris J, et al. Childhood trajectories of anxiousness and disruptiveness as predictors of suicide attempts. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:1015-1021.

Castellanos D, Hunter T. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. South Med J. 1999;92:946-954.

Grant P, Lougee L, Hirschtritt M, et al. An open-label trial of riluzole, a glutamate antagonist, in children with treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17:761-767.

Kurlam R, Johnson D, Kaplan EL. Streptococcal infection and exacerbations of childhood tics and obsessive-compulsive symptoms: a prospective blinded cohort study. Pediatrics. 2008;121:1188-1197.

MacMaster FP, O’Neill, Rosenberg DR. Brain imaging in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:1262-1272.

Mallet L, Polosan M, Jaafari N, et al. Subthalamic nucleus stimulation in severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2121-2134.

March JS, Franklin ME, Leonard H, et al. Tics moderate treatment outcome with sertraline but not cognitive-behavior therapy in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:344-347.

Pavone P, Parano E, Rizzo R, et al. Autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infection: sydenham chorea, PANDAS, and PANDAS variants. J Child Neurol. 2006;21:727-736.

Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) Team. Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: the Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:1969-1976.

Ramsawh HJ, Chavira DA, Stein MB. Burden of anxiety disorders in pediatric medical settings. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:965-972.

Rockhill C, Kodish I, DiBattisto C, et al. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Curr Prob Ped Adolesc Med. 2010;40(4):65-100.

Roy-Byrne PP, Craske MG, Stein MB. Panic disorder. Lancet. 2006;368:1023-1032.

Tyrer P, Baldwin D. Generalized anxiety disorder. Lancet. 2006;368:2156-2166.

Walkup JT, Albano AM, Piacentini J, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2753-2766.