CHAPTER 8 Anxiety and post-traumatic disorders

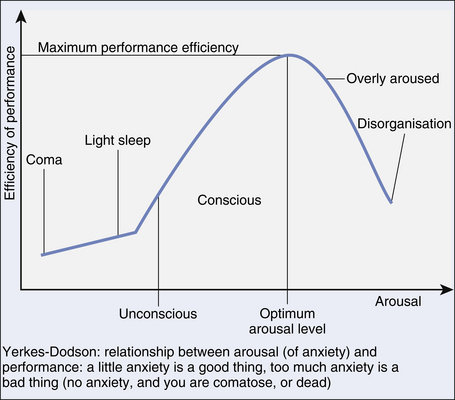

Anxiety is, of course, a perfectly normal phenomenon. Indeed, without any anxiety we would be comatose or dead! To perform optimally in any given situation, we do need a certain amount of anxiety/arousal. Sometimes, it is appropriate for us to have a massive surge of anxiety, such as when we are confronted by a life-threatening situation: the so-called ‘fight or flight’ response. However, if one experiences too much anxiety most of the time and/or in excess to the level of ‘threat’, it can become incapacitating and un-useful. The Yerkes-Dodson curve (Fig 8.1) demonstrates this.

The precise point at which anxiety becomes so severe as to constitute a ‘disorder’ is open to conjecture, and needs to be assessed on an individual basis. The general rubric that the anxiety response is excessive/prolonged, causes the individual distress and impairs their psychosocial functioning is a useful enough starting point. Note, though, that some anxious people are so good at avoiding their feared situation that they might effectively avoid ever becoming anxious, yet be objectively impaired in terms of the restriction this places on their life. The current DSM–IVTR and ICD–10 classifications of the anxiety disorders are summarised in Table 8.1.

TABLE 8.1 Classification of anxiety disorders according to DSM–IVTR and ICD–10

| DSM–IVTR (synopsis) | ICD–10 (synopsis) |

|---|---|

| Panic disorder | Panic disorder |

| Agoraphobia without panic | Agoraphobia |

| Social anxiety disorder | Social phobia |

| Specific phobia | Specific phobia |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | Generalised anxiety disorder |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | Obsessive-compulsive disorder |

| Acute stress disorder | Acute stress reaction |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | Post-traumatic stress disorder |

Anxiety symptoms can be seen as a manifestation of a number of physical and psychiatric disorders, and these need to be assessed and treated in their own right (see Box 8.1).

A panic attack is essentially a severe burst of anxiety, be it in response to a particular stimulus, or ‘out of the blue’. There are somatic and psychic/cognitive features, as shown in Box 8.2. By definition, the attack should reach a peak within 10 minutes, but in many cases it is very abrupt. Panic attacks resolve with time, and can be attenuated with slow-breathing techniques.

Panic disorder

Of themselves, panic attacks carry no diagnostic specificity, and many people have them during their lives. Sometimes, they are an indicator of an underlying physical problem, and these need to be investigated where appropriate (see Box 8.1).

Phobic disorders

Once anxiety becomes linked to a certain situation or thing and results in avoidance thereof to the extent that this impedes everyday life, the individual should be considered to have a phobic disorder. The important thing here is that therapeutically, if avoidance is demonstrated, then the psychological technique of exposure/response prevention (EX/RP) can be employed. Essentially, this involves mapping the behaviours, fears and avoidances, and helping the patient tackle their fears in a structured hierarchical way (i.e. starting with something relatively easy, conquering that, then moving to the next step). An analogy is engaging in a step-wise exercise program, with the clinician as the coach.

Agoraphobia (literally ‘fear of the market place’) is characterised by fear of situations where the individual feels trapped. These include busy supermarkets, heavy traffic and public transport; open spaces are also often feared and avoided, and home is seen as ‘safe’, resulting in the ‘housebound housewife’. DSM–IVTR links agoraphobia specifically among the phobic disorders, with panic disorder, though panic can actually occur with any of the phobic disorders. More often than not, agoraphobia begins with a panic attack in an agoraphobic situation, resulting in withdrawal from the situation and subsequent avoidance. Technically, agoraphobia can occur without panics, but this is usually seen in those patients who habitually avoid the situations in which they might panic. Treatment is psychoeducation, EX/RP, and, if required, SSRIs or serotonergic and noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). In general, medications should be used in the anxiety disorders if the features in Box 8.3 pertain.

BOX 8.3 General guidance about when to prescribe antidepressants in people with anxiety disorders

Treatment includes cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), especially dealing with the core negative cognition of making a fool of oneself in front of others, and an hierarchical approach to the behavioural avoidance: group treatment can be particularly useful. SSRIs and SNRIs are useful adjuncts, with the general guidance shown in Box 8.3.

Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD)

Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) has become something of a residual diagnosis, being effectively ‘trumped’ by panic disorder. There is considerable comorbidity with depression, and some researchers consider it should be subsumed under the affective disorders. However, a clinical syndrome with predominant ‘free floating’ anxiety is certainly seen in practice. Female predominant, GAD usually begins insidiously, even seeming to grow out of an anxious personality structure. Symptoms include anxiety about just about everything, including what might or might not happen. Many patients with GAD also focus on their physical health, with a strong tendency to somatise and present to doctors with physical symptoms (see Ch 11). Muscle tension, headaches and abdominal discomfort are common. Sleep is often restless and unrefreshing.

Treatment includes psychoeducation and in particular teaching relaxation techniques. Problem solving is useful: the patient is taught about prioritising important tasks and tackling them in a paced manner, rather than being so overwhelmed by everything that nothing is achieved. More formal CBT can be usefully employed, with a focus on challenging catastrophic thinking and modifying associated un-useful behaviours, such as doctor-shopping or benzodiazepine abuse. SSRIs and SNRIs are a useful adjunct, particularly in the face of mood disturbance.

CASE EXAMPLES: anxiety disorders

Generalised anxiety disorder

A 38-year-old woman was referred by a physician colleague who had investigated her extensively to find a cause of her headaches, but who could find no obvious physical pathology. The woman said she had always been a worrier and in particular had had ongoing concerns regarding various aspects of her physical health. She described being constantly tense, that she worried about ‘everything and nothing’ and had restless and unrefreshing sleep. Her mood was low, she lacked energy and concentration, and was concerned her husband was going to leave her because she considered herself ‘such a pain to live with’. Treatment included a full exploration of symptoms, and an assessment of mood, including of suicide risk. She was offered extensive psychoeducation (with her husband) about the anxiety-depressive spiral. Simple psychological measures such as problem solving, and the introduction of an SNRI (started at low dose and built up slowly), helped both her mood and her anxiety.

Post-traumatic syndromes

avoidance of places or things associated with the event, and triggering of symptoms in response to reminders of the event; and emotional numbing, or detachment from others and the world around one, and

avoidance of places or things associated with the event, and triggering of symptoms in response to reminders of the event; and emotional numbing, or detachment from others and the world around one, andArguably, it is this last set of symptoms that sets PTSD apart from other psychiatric disorders.

Treatment of PTSD is complex, and needs to encompass all facets of the disorder, and also address, where indicated, comorbid substance use, depression and pain syndromes. Specific approaches include a variety of psychological treatments, including CBT and EX/RP. Group therapy can be particularly useful in terms of mutual support from group members, and the other benefits of the group process, as outlined in Chapter 14. SSRIs and SNRIs are commonly prescribed for anxiety and depressive symptomatology. Hypnotics or low dose atypical antipsychotics (see Ch 13) can assist sleep. Benzodiazepines are best avoided apart from initial short-term use.

References and further reading

Andreasen N.C. Posttraumatic stress disorder: psychology, biology, and the Manichaean warfare between false dichotomies. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:963-965.

Castle D., Hood S., Kyrios M., editors. Anxiety disorders: current controversies, future directions. Melbourne: Australian Postgraduate Medicine, 2007.

Gelder M. Panic disorder: fact or fiction? Psychological Medicine. 1989;19:277-283.

Marshall R.D., Spitzer R., Liebowitz M.R. Review and critique of the new DSM–IV diagnosis of acute stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:1677-1685.

Orr K.G.D., Castle D.J. Social phobia: shyness as a disorder. Medical Journal of Australia. 1998;168:55-56.

Tyrer P. Classification of anxiety. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1984;144:78-83.