Chapter 4 Anxiety

With contribution from Dr Katherine Sevar

Introduction

Anxiety disorders are amongst the most common disorders suffered by the Australian population, with approximately 7% of men and 12% of women affected each year.1

Anxiety disorders are classically under-reported to GPs by the community, with on average only one-fifth of people with anxiety as their primary complaint seeking professional help in 2002.2 The reasons cited for this include preferring to individually manage the condition and a desire to pursue self-help strategies.3 Given this finding, it may come as a surprise that anxiety is actually one of the commonest presentations to GPs — when a sub-study of BEACH (Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health) surveyed a random sample of 379 GPs they discovered that the 3 conditions placing the greatest demand on an individual practitioner’s time were anxiety, depression and back pain.4 Recent statistics suggest 1–2% of the adult population suffer panic disorders — common risk factors include female gender, low socioeconomic status and anxious childhood temperament — and this is associated with significant suicide risk, all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease.5

Sub-classifications of anxiety disorders

There are sub-classifications of anxiety disorders according to DSM-IV criteria, which include generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, agoraphobia, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). There is significant co-morbidity with anxiety disorders and depression and substance abuse.1

Panic disorder and agoraphobia

Panic attacks can be spontaneous or can occur in relation to a specific stimulus. They include somatic features and cognitive features. The somatic features may include palpitations, chest pain, a feeling of choking, nausea, sweating, dizziness. The cognitive features may include acute fear of dying, losing control, going mad and a need to escape from the current situation and there can also a be a feeling of depersonalisation or non-realisation. In up to 90% of cases, these attacks lead to an avoidance of situations where escape may not be possible — agoraphobia.6 Common associations occur with depression, substance abuse and interpersonal difficulties. Panic disorder is currently treated with anti-anxiety medication and a mix of CBT and exposure therapy. Breathing techniques for the short-term management of panic attacks are advocated and benzodiazepines should only be used in the short-term.

Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)

Obsessions can be intrusive thoughts, images or impulses which create anxiety in an individual as they feel unable to control how, when or where these obsessive thoughts may occur. Compulsive behaviour develops as an attempt to relieve the anxiety created by the obsession. Compulsions can include extremely ritualistic behaviours and a need to follow a set routine. Although the compulsions initially relieve anxiety they will over time relieve less anxiety, resulting in them becoming more elaborate and taking up more of the individual’s time. OCD becomes a problem when these behaviours interfere with ordinary life. Current treatment strategies include medication with a selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor (SSRI) or clomipramine (a serotonergic tricyclic antidepressant) in combination with CBT.

Trends in integrative medicine for anxiety

Research describing long-term trends in complementary medicine (CM) use in the US reported that complementary therapies were used by 57% of people reporting anxiety attacks and 66% of patients consulting a physician for treatment of anxiety. Those surveyed perceived that the efficacy of complementary medicines for anxiety were comparable to conventional drug treatment.7

Lifestyle medicine

Lifestyle factors such as chronic stress, poor nutrition, caffeine, smoking, obesity, alcohol and substance abuse may initiate or perpetuate the symptoms of an anxiety disorder8 and there is an increasing interest among medical and health practitioners to address these lifestyle factors in combination with pharmacotherapy and psychological therapies for anxiety disorders.9

Mind-body medicine

Psychological therapies

Counselling for anxiety in general practice

Patient-centred care has also become a major focus in mainstream medicine and is being evaluated and promoted within general practice in particular.10 Active listening, compassion and empathy are vital factors in the counselling of those patients with an anxiety disorder. Patients who feel their doctors listen to them, and respond with empathy, feel they have greater overall improvement across many conditions.11 In a study of 309 women seeking psychological support, GPs with good listening skills and those who provided longer consultation times were highly valued.12 Women who received referral, counselling and relaxation advice from their GP reported a higher degree of satisfaction.

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) and group therapy

CBT is a talking-based therapy arising from the link between thoughts, feelings and behaviour.13 CBT is a valuable tool for the management of anxiety and it is the first-line treatment for adults and children. The central beliefs of CBT and interventions for anxiety disorders include cognitive restructuring, relaxation, breathing techniques, graded exposure to anxiety provoking situations, problem solving, assertiveness training and social skills development. In an 8-week program,14 CBT including exposure therapy was better than placebo (supportive, non-directive counselling) or moclobemide for the treatment of panic disorder with agoraphobia. Long-term benefits of CBT occurred when used in combination with moclobemide. Self-help CBT programs available on the internet may also be of help in allaying test anxiety. In a study of 90 university students who were randomised to CBT or a control program, both on the internet,15 anxiety was rated before and after treatment and 53% of the CBT group showed a significant improvement in anxiety related to the test but only 29% of the control group demonstrated benefit. This study supports the use of CBT on the internet for the treatment of test anxiety.

Research supports the role of CBT for social phobia in both group and individual formats.16 In this study, symptom measures completed at the beginning and end of group therapy found improvement in group cohesion and social anxiety symptoms over time, as well as improvement on measures of general anxiety, depression, and functional impairment.

Clinical guidelines and treatment recommendations by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) are summarised in Table 4.1.17

Table 4.1 RANZCP clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of panic disorder and agoraphobia

| Education for the patient and significant others |

∗The presence of severe agoraphobia is a negative prognostic indicator, whereas comorbid depression, if properly treated, has no consistent effect on outcome

(Source: RANZCP Guidelines Team for Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 2003;37:641–56)

Drugs

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) and lack of family cohesion are known risk factors for drug use such as marijuana and alcohol use.18 Combination of SAD with either alcohol or drug use is associated with higher comorbidity in anxious individuals and may further aggravate anxiety.19–22 Patients should be advised to avoid using alcohol and drugs for alleviation of anxiety symptoms.

Mind–body therapies

relevant evidence was available for bibliotherapy, dance and movement therapy, distraction techniques, humour, massage, melatonin, relaxation training, autogenic training, avoiding marijuana, a mineral-vitamin supplement (EMPower +) and music therapy.23

The authors concluded these therapies might be useful but warned more trials are recommended.

Autogenic training (AT) and biofeedback

A systematic review in 2000 evaluated all of the controlled trials investigating AT and identified 8 such trials although the majority of these trials were methodologically flawed.24 Seven trials reported positive effects of AT in reducing stress and 1 study showed no such benefit. The authors noted no firm conclusion could be drawn from these studies.

However, a recent meta-analysis of AT assessing 7 clinical trials found that 3 trials with control groups showed a positive outcome and that 1 further case controlled trial was also positive but the remaining 3 trials showed no difference. There is encouraging evidence from more recent trials that AT can reduce stress and anxiety in adults, as well as children and adolescents. 25–28

There are some preliminary results for the use of biofeedback in adults.29, 30

Bibliotherapy

Bibliotherapy uses reading as a healing therapy by tailoring the reading material to the patient’s current life situation. There have been several meta-analyses completed considering bibliotherapy for the treatment of anxiety and they concluded that bibliotherapy appeared to work best when there was a well-circumscribed problem; that is, a specific phobia,31 but that it had very little effect on OCD or panic disorder.32 It appeared to be more effective in highly motivated individuals.

A recent study focusing on social phobia found that a self-help program consisting of an 8-week self-directed CBT with minimal therapist involvement for social phobia based on a widely available self-help book was superior to wait-list on most outcome measures.33 Benefits were observed with reductions in social anxiety, global severity, general anxiety, and depression following the study and at 3-months follow-up.

Dance therapy

In a review of complementary therapies for anxiety disorders in 2004, dance therapy was considered to have encouraging evidence for people with self-identified anxiety, test anxiety and other anxiety problems in clinical groups. The authors considered it would be worth exploring whether dance therapy may have a greater anxiolytic effect than physical exercise.35

Hypnotherapy

A growing body of research appears to support the role of hypnosis in the treatment of anxiety. In a large prospective, randomised single-centre study published in the Lancet,36 241 patients undergoing percutaneous vascular and renal procedures were randomised to receive intraoperative standard care (n = 79), structured attention (n = 80) or self-hypnotic relaxation (n = 82). All patients had access to intravenous analgesia (fentanyl and midazolam). Hypnosis had a more pronounced effect on pain and anxiety reduction. Pain increased linearly in both the standard and attention groups, but remained flat in the hypnosis group. With time, anxiety decreased in all 3 groups, but at a higher rate in the hypnosis group. Drug use was twice as likely in the standard group than the attention and hypnosis groups. Only 1 patient became haemodynamically unstable in the hypnosis group compared with 10 and 12 in the attention and standard groups respectively.

In a small RCT37 of paediatric cancer patients, 45 children aged 6–16 years were randomised into 1 of 3 groups: local aesthetic, local aesthetic plus hypnosis, and local anaesthetic plus attention for the relief of lumbar puncture-induced pain and anxiety. Patients in the local anaesthetic plus hypnosis group reported less anticipatory anxiety and procedure-related pain and anxiety, and they were rated as demonstrating less behavioural distress during the procedure. The magnitude of treatment benefit depended on their level of hypnotisability and this benefit was maintained when patients used hypnosis independently. Another small hospital study,38 assessing pre-operative anxiety, randomised adult patients into 3 groups: a hypnosis group (n = 26) who received suggestions of wellbeing; an attention-control group (n = 26) who received attentive listening and support without any specific hypnotic suggestions, and a ‘standard of care’ control group (n = 24). Anxiety was assessed before and after their operation. Patients in the hypnosis group were significantly less anxious following surgery, compared with patients in the attention-control group and the control group. Moreover, the hypnosis group reported a significant decrease of 56% in their anxiety level pre-operatively, whereas, the attention-control group reported an increase of 10% and the control group an increase of 47% in their anxiety. In conclusion, the researchers found that ‘hypnosis significantly alleviates preoperative anxiety’. Hypnosis plays a useful role in allaying anxiety for a number of other operative procedures, such as colonoscopy.39

A larger well conducted prospective trial published in Pain 2006, randomised 236 women for large core needle breast biopsy to receive standard care (n = 76), structured empathic attention (n = 82), or self-hypnotic relaxation (n = 78) during their procedures. Patients were rated for pain and anxiety every 10 minutes during their care.40

A systematic review of studies shows that hypnotherapy is highly effective for patients with refractory irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and alleviating anxiety, but definite efficacy of hypnosis in the treatment of IBS remains unclear due to limited number of controlled trials.41

A recent review of the literature identified 60 publications that found hypnotherapy may be useful for a wide range of disorders and problems in children, and is particularly valuable in the treatment of anxiety disorders and trauma-related conditions, especially in conjunction with family therapy and CBT.42

School refusal is considered a form of anxiety. A small study increased school attendance by using a form of self-hypnosis on children suffering school refusal.43

A review of the research acknowledges the important role of hypnosis in health care, especially for difficult to treat patients and for reducing anxiety.44 Hypnosis can successfully be used to help alleviate peri-operative anxiety and stress in a hospital setting.45

Meditation

A Cochrane review could not conclude from 2 small studies if meditation alone is effective for anxiety.46 The researchers identified 2 randomised controlled studies of moderate quality that used active control comparisons, meditation, relaxation, or biofeedback. Anti-anxiety drugs were used as standard treatment. The duration of trials ranged from 12 to 18 weeks. In 1 study, transcendental meditation showed a reduction in anxiety symptoms compared with biofeedback and relaxation therapy.46 Another study compared Kundalini Yoga with relaxation/mindfulness meditation, which showed no statistically significant difference between groups.46 However, the overall dropout rate in both studies was high (33–44%). Neither study reported on adverse effect of meditation. More studies are warranted.

Relaxation therapies

Patients with an anxiety disorder should be encouraged to learn various relaxation methods as there is strong research demonstrating their benefit. A systematic review of mind–body therapies in 2007 concluded that there was now robust evidence for the use of relaxation therapy in anxiety and insomnia.47

A recent meta-analysis of the literature, inclusive of 27 studies, found relaxation training had a significant beneficial effect in the treatment of anxiety.48 Efficacy was higher for meditation and for longer treatments. Implications and limitations are discussed.

A separate review found that when the different classifications of anxiety disorder were considered separately then relaxation was most effective for GAD, panic disorder, test anxiety and dental phobia, but that it was less effective for PTSD, OCD and specific phobias.35

Music therapy

Listening to music may also help alleviate pre-operative anxiety. A randomised controlled trial study of 180 patients having day surgery was conducted to assess anxiety before and after listening to patient-preferred music.49

Patients were randomised to either an intervention (n = 60), placebo (n = 60) or control group (n = 60). Statistically, music significantly reduced the state of anxiety level in the music (intervention) group compared with the placebo and control groups, with no differences found between socio-demographic or clinical variables such as gender or type of surgery. Another study on patients undergoing cardiac surgery also demonstrated significant reduction in anxiety and pain levels in those receiving music therapy.50 Eighty-six patients (69.8% males) were randomised to 1 of 2 groups; 50 patients received 20 minutes of music (intervention), whereas 36 patients had 20 minutes of rest in bed (control). Anxiety, pain, physiologic parameters, and the use of analgesia (opioid) consumption were measured before and after the 20-minute period. The music therapy group demonstrated a significant reduction in anxiety and pain compared with the control group. There was no difference in systolic or diastolic blood pressures, or heart rate. Also, there was no reduction in the use of analgesia (opioid) usage in the 2 groups.

Music therapy may also play a role in palliative care51 where research demonstrated statistical improvements in mood and anxiety, and in pain control and reducing anxiety in patients during wound dressings.52

Religion

Religiosity and spirituality have long been seen as a worthwhile buffer against dealing with life’s problems and stresses and a large population study over 9 years showed that all-cause mortality was significantly reduced and life expectancy increased (75 years compared with 82 years) for regular churchgoers. This was not explainable by lifestyle and social variables.53 However, there has been only 1 randomised trial to date which added a religious component to standard pharmacotherapy for GAD and this showed improvement at 3 months but this did not appear to be sustained at 6 months.54

Creativity

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is often associated with distressing, intrusive, anxious preoccupations with control of eating, weight and shape. One study of 38 women with AN admitted to a specialised eating disorder unit were offered knitting lessons and free access to supplies.55 Of interest, patients reported a significant subjective reduction in anxious preoccupation when knitting, with 74% reporting reduction in the intensity of their fears and thoughts and their minds cleared of eating disorder preoccupations. In addition, 74% reported it had a calming and therapeutic effect and 53% reported it provided satisfaction, pride and a sense of accomplishment. This study demonstrates that creative activities may be of help with anxiety symptoms experienced with AN and more research is required, particularly to see if other creative areas, such as painting and pottery, may also be of help.

Behavioural interventions — summary

The evidence currently suggests using behavioural interventions before considering pharmacotherapy in insomnia. A meta-analysis examining the evidence for behavioural modification CBT, relaxation and behavioural treatment alone, found 23 randomised controlled trials and concluded there were moderate to large effect sizes showing an improvement in sleep for all 3 modalities and the results were the same in both middle-aged adults and older adults (55+).56 A review of the increasing evidence for mind-body therapies in 2007 concluded that there was now robust evidence for the use of relaxation therapy in anxiety and insomnia.57

Sleep

Anxiety and insomnia are highly co-morbid conditions and physiologically anxiety and low mood increase corticotrophin releasing hormone (CRH) and other stress hormones secreted from the adrenal glands which, in turn, have negative impact upon sleep patterns.58 A large health survey conducted in Germany (n = 4186) found that individuals with anxiety disorder and insomnia experienced significantly worse mental-health related quality of life and increased disability.59 Most anxiety disorders were moderately associated with reduced sleep quality with GAD (AOR 3.94, 95% CI 1.66-9.34) and SAD (AOR 3.95, 95% CI 1.73-9.04) having the strongest relationship to reduced quality of life scores. For more information see Chapter 22.

Melatonin

In a systematic review of melatonin, 6 RCTs were included which concluded that there was sufficient evidence to show that low dose melatonin improves sleep quality.60

Multiple studies have demonstrated that oral melatonin can be an effective premedication for surgery, improves peri-operative analgesia, can act as an anti-anxiolytic, enhances analgesia and promotes better operating conditions under topical anaesthesia, such as in cataract surgery, even reducing the risk of intraocular pressure in eye surgery.61, 62 In 1 RCT, the anxiolytic effect of 5mg oral melatonin (and clonidine) resulted in reduced postoperative pain, and the need for morphine consumption reduced by more than 30% in patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy under general anaesthetic; far greater than placebo.63 The beneficial effects of both melatonin and clonidine were equivalent.

In a recent prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial in a community-living population of 22 elderly with a history of sleep disorder complaints of whom 14 were receiving hypnotic drug therapy, participants were randomised to either 2 months of melatonin (5mg/day) and 2 months of placebo. Sleep disorders, mood, behaviour and level of depression and anxiety were evaluated.64 Melatonin treatment for 2 months significantly improved sleep quality scores and mood levels, especially for depression and anxiety, and facilitated discontinuation of hypnotic drugs compared with placebo.

Acupuncture

A Cochrane review in 2007 reviewed acupuncture as a treatment for insomnia and found that from the small number of RCTs, together with the poor methodological quality and significant clinical heterogeneity, the current evidence is not sufficiently extensive or rigorous to support the use of acupuncture in the treatment of insomnia.65

Sunshine

There is increasing evidence pointing to the important role of vitamin D in a multitude of disease processes, from multiple sclerosis to diabetes mellitus. Vitamin D deficiency may be associated with anxiety and depression in those suffering from fibromyalgia and in research from Northern Ireland, patients with vitamin D deficiency (<25 nmol/l) had higher Hamilton Anxiety and Depression Score (HADS), compared with patients with insufficient levels (25–50 nmol/l) or with normal levels (> 50 nmol/l).66 The exact nature and direction of the causal relationship remains unclear but further research is warranted.

Vitamin D deficiency is prevalent among older adults, and research suggests there may be an association between Vitamin D deficiency and basic and executive cognitive functions, depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia.67 Vitamin D activates receptors on neurons in regions implicated in the regulation of behaviour, stimulates neurotrophin release, and protects the brain by buffering antioxidant and anti-inflammatory defences against vascular injury and improving metabolic and cardiovascular function.

Environment

Smoking

Smoking is well recognised as being a behavioural response to stress and stress management plays an important role in cessation of smoking. Nicotine affects a wide range of neurotransmitters involved in the development of anxiety, including glutamate, GABA, nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and serotonin. It is now widely believed that smoking may increase anxiety levels and that smokers are locked into a cycle where they suffer the short-term anxiety associated with nicotine withdrawal only to relieve that by smoking, therefore perpetuating the problem. There has been some research into the general population suggesting that overall anxiety levels fall after smoking cessation68 but no RCTs have been conducted in people with anxiety disorders.

Physical activities

Exercise

The beneficial effect of exercise on anxiety disorders has been largely accepted. The most recent meta-analysis conducted in 2008, included only RCTs (n = 49) and came to the overwhelming conclusion that exercise is effective69 in reducing anxiety compared with no-treatment control groups. Exercise groups also showed greater reductions in anxiety when compared to groups receiving other anxiety reducing treatment.

However, when a large population-based sample of identical twins (n = 5952) was followed between their ages of 18–50, from 1991–2002, in genetically identical twin pairs, the twin who exercised more did not display fewer anxious and depressive symptoms than the co-twin who exercised less.70 Longitudinal analyses showed that increases in exercise participation did not predict decreases in anxious and depressive symptoms. These researchers concluded that although regular exercise is associated with reduced anxious and depressive symptoms in the population at large, the association does not appear to be because of the causal effects of exercise.

There has been more encouraging evidence in the treatment of anxiety and panic attacks, showing aerobic exercise to be as effective as clomipramine in the treatment of panic disorder.71

Yoga

Yoga is gaining in popularity internationally, both for exercise and as a method of relieving stress. There have been several positive RCTs conducted in yoga. An RCT in women with breast cancer undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy and 6 weeks of chemotherapy following surgery (n = 38) were randomised to receive either a weekly 60 minute yoga class or supportive therapy and the women in the yoga group reported an overall decrease in both self-reported state anxiety (p<0.001) and trait anxiety (p = 0.005).72 There was also a positive correlation between anxiety states and traits with symptom severity and distress during conventional treatment intervals. Another controlled trial found yoga to be superior to diazepam for generalised anxiety but patients were allowed to choose their allocation of treatment (i.e. yoga or diazepam).73

Nutritional influences

Alcohol

Alcohol is a well-known, well-accepted commonly used method to reduce anxiety and there have been several placebo-controlled trials conducted which confirm the short-term anti-anxiolytic effects of alcohol in those with panic disorder,74 social phobia75 and GAD.76 However, in the long-term, anxiety and alcohol abuse can become comorbid conditions as tolerance to alcohol develops and greater amounts are required to produce the same effect. Initially, alcohol affects GABA receptors in the same way as benzodiazepines, but with chronic alcohol use, GABA receptor tone may decrease, which can precipitate anxiety.77 For individuals with chronic alcohol use, reduced anxiety has been reported from uncontrolled studies following the cessation of alcohol.78

Caffeine

Maximal lifetime caffeine intake and caffeine-associated toxicity and dependence are moderately associated with risk for a wide range of psychiatric and substance use disorders.79 A study of 376 young British adults showed that estimated daily caffeine consumption increased with age, and was associated with smoking and greater alcohol consumption.80 These researchers found the level of caffeine consumption was not associated with impulsivity, sociability, extraversion or trait anxiety.

Caffeine challenge studies have been conducted as randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trials which uniformly confirm that caffeine exacerbates anxiety in those suffering from GAD,81 panic disorder82 and social phobia.83

In the community, there is a high rate of discontinuation of caffeine in people with anxiety disorders because of the self-reported increase in symptoms following ingestion of caffeine and this is supported in retrospective analyses84, 85 and a case series of individuals,86 who experienced a reduction in anxiety following the cessation of caffeine. Based on the findings of the studies overall, anxiety sufferers should avoid high doses of caffeine. Other symptoms associated with anxiety and high caffeine intake include palpitations and muscle tension. However, there have been no RCTs conducted examining the effect of reduction or abstention from caffeine.

Nutritional supplements

Fish oils (omega-3)

Essential fatty acids help improve neuronal membrane structure and are present in the nervous system and are involved in endocrine and immune functions, hence their potential benefit for various brain-related disorders. Several clinical studies show beneficial effects of omega-3 fatty acids including improved mood profile, increased vigour, reduced anger, and anxiety and depression states.87

A recent study demonstrated that a polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) mixture of omega-3 and omega-6 (ratio of 1:4) may improve test anxiety symptoms.88 Psychologists identified 126 male college students as test anxiety sufferers. Thirty-eight received placebo (mineral oil) and 88 received the PUFA mixture over 3 weeks. Seventy other students who did not suffer test anxiety served as the control group. Behavioural variables associated with test anxiety, such as appetite, mood, mental concentration, fatigue, academic organisation and poor sleep, all significantly improved with the PUFA mixture, as well as lowering elevated cortisol level, with a corresponding reduction of anxiety compared with placebo and control. Another study of 27 untreated, non-depressed patients with social anxiecty disorder (SAD) and 22 controls found lower erythrocyte n-3 PUFA concentrations in the patients.89 Significant inverse correlations were obtained between levels of n-3 PUFAs and symptom severity in patients with SAD, thereby opening new therapeutic options.

A 3-month double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial in substance abusers (n = 24) found after supplementation with 3g of n3-PUFA for 3 months their anxiety was significantly improved (p = 0.01) and this was sustained for 6 months after the end of the intervention (p = 0.042).90 However, a recent systematic review found that inconsistencies still remain in the evidence for fish oil supplementation in anxiety disorders, both in study methodology and findings, so further research is clearly warranted.91

Inositol

Inositol is an isomer of glucose and it may theoretically have a psychoactive effect because of its involvement in a second messenger system for some serotonin and noradrenaline receptors. There have been 2 RCTs with small sample sizes (average 20) using inositol 12–18grams/day in panic disorder. Both of these trials showed it to be superior to the placebo,92 and in 1 trial it was as effective as fluvoxamine.93 The treatment duration in both trials was 4–6 weeks only. An RCT in PTSD found that it was not effective94 and in 1 further RCT in OCD it was superior to placebo95 but not better than an SSRI.96 It appears that further long-term trials could be warranted.

Magnesium

The rationale for supplementation with magnesium in anxiety is based on the hypothesis that magnesium will be depleted in high stress leading to deficiency which may exacerbate the symptoms of anxiety.97 There have currently been no RCTs for magnesium alone in the treatment of anxiety but 1 RCT comparing magnesium as an adjunct to anxiolytics in women with a mixed anxiety/depression (n = 20) over a 10-day period found that those in the magnesium group improved more than those in the placebo group.98 A recent Cochrane report identified a double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study of 44 women with premenstrual syndrome (average age 32 years) randomised to take consecutively all 4 of the following treatments daily for 1 menstrual cycle: (1) 200mg Mg oxide, (2) 50mg vitamin B6, (3) 200mg Magnesium + 50mg vitamin B6 and (4) placebo.99 The report showed no overall difference between individual treatments, but compared with baseline, a synergistic effect was demonstrated with combined 200mg/day magnesium + 50mg/day vitamin B6 on reducing anxiety-related premenstrual symptoms (nervous tension, mood swings, irritability, or anxiety) during 1 menstrual cycle.100

Multivitamins

Whilst a balanced diet containing as many vitamins, minerals and trace elements from food sources as possible would be advocated for anyone with an anxiety disorder, the evidence for specific multivitamin supplementation remains unconvincing. The only RCT to date was conducted using Berrocatm, a multivitamin (vitamin B complex, vitamin C, calcium and magnesium) manufactured by Roche, in a group of healthy individuals and whilst those in the intervention group reported increased psychological wellbeing, these results have not been replicated in individuals with an anxiety disorder.101

Herbal medicine

A recent systematic review of the literature identified 7 RCTs testing herbal mono-preparations and 1 systematic review of 8 different herbs in alleviating anxiety. It concluded there are a ‘lack of rigorous studies in this area and that only kava has been shown beyond reasonable doubt to have anxiolytic effects in humans’.102

Kava Piper methysticum

Kava, also known as kava kava or Piper methysticum, is a member of the pepper family and traditionally used by Pacific Islanders for social and ceremonial drink. Some Aboriginal communities are also known to use kava. A recent Cochrane review identified 12 double-blind RCTs (n = 700).103 Only 7 of these studies (n = 380) were included in the meta-analysis using the total score on the Hamilton Anxiety (HAM-A) scale as a common outcome measure. The reviewer’s concluded from these results ‘a significant effect towards a reduction of the HAM-A total score in patients receiving kava extract compared with patients receiving placebo (weighted mean difference: 3.9)’. They found adverse events were mild, transient and infrequent for short-term treatment (1 to 24 weeks). They also conclude the ‘effect lacks robustness and is based on a relatively small sample’ and rigorous larger, long term trials are required.103

Despite the findings of the reviews, there have been mounting international concerns over reports of hepatotoxicity and deaths from liver failure associated with high doses and ethanolic extracts of kava-containing medicines, including 1 case of a fatality in Australia following acute liver failure, associated with a kava-containing medicine. Following a Therapeutic Goods Administration safety review of kava-containing medicines,104 there is now a limit on the maximum amount of kava lactones (a group of constituents found in Piper methysticum) of 125mgs permitted per dosage form (tablet or a capsule), with a maximum daily dose of no more than 250mg of kava lactones. Also, labels on Australian-made kava products contain warnings that it may harm the liver and to stop using the product if adverse liver symptoms develop.

Sage Salvia officinalis

A recent double-blind, placebo, cross-over study of 30 healthy participants aimed to assess the effect of sage (Salvia Salicia officinalis) to enhance mnemonic performance and mood.105 Previous studies with sage indicated it possesses in vitro cholinesterase inhibiting properties. The participants were randomised to placebo, 300–600mg dried sage leaf and assessed every 7 days on 3 occasions. Both doses of sage led to improved ratings of mood, with the lower dose improving anxiety and the higher dose increasing alertness, calmness and contentedness compared with placebo.

St John’s wort Hypericum perforatum

There is high-level evidence that St John’s wort is effective in depression and as anxiety is often co-morbid with depression it may have an indirect effect on anxiety. Case reports to date also indicate it may be of help in alleviating anxiety symptoms.106

St John’s wort is helpful in mild, moderate and severe depression and as anxiety can be a symptom of depression this may explain its observed benefit.107, 108

Valerian Valerian officinalis

Valerian herb is usually indicated for the treatment of insomnia. Valerian has been investigated as a hypnotic with previously mixed results, but the most recent systematic review found that, overall, although valerian is a safe herb associated with only rare adverse events the evidence does not support the clinical efficacy of valerian as a sleep aid for insomnia.109 A recent Cochrane review identified 1 small RCT involving 36 patients with GAD.110 This was a 4-week pilot study of valerian, diazepam and placebo. Whilst there were no significant differences between the valerian and placebo groups in Hamilton Anxiety (HAM-A) total scores, there were also no significant differences in HAM-A scores between the valerian and diazepam groups. However, based on STAI-Trait scores, significantly greater symptom improvement was identified in the diazepam group. Side-effect profile and drop-out rates were similar in all 3 groups. The author’s concluded there ‘is insufficient evidence to draw any conclusions about the efficacy or safety of valerian compared with placebo or diazepam for anxiety disorders’ and ‘larger samples and comparing valerian with placebo or other interventions used to treat anxiety disorders, such as antidepressants, are needed’.110

Potential but rare side-effects, such as paradoxical hyperactivity and insomnia, have been associated with valerian use and delirium on withdrawal of valerian.111

Other herbs

Other herbs with potential anti-anxiolytic effects include passiflora — shown to be equivalent to oxazepam in a small pilot double-blind RCT112 — Panax ginseng,113 German chamomile,114 lemon balm115 and valerian,116, 117 although research for these are minimal and more research is required.

Herbal combinations

Crataegus oxyacantha, Eschscholtzia californica and magnesium

Two plant extracts Crataegus oxyacantha and Eschscholtzia californica combined with magnesium were assessed for clinical efficacy in mild-to-moderate anxiety disorders under usual general practice prescription conditions.118 This large scale study of 264 patients (81% female; mean age: 44.6 years) with generalised mild–moderate anxiety were randomised into 2 groups: 130 received the combined herbs and magnesium (Sympathyl) and 134 a placebo for 3 months. The results demonstrated clinical improvement in anxiety scores in the treatment group compared with placebo group. The mean difference between final and pre-treatment scores were, for the treatment group and placebo groups respectively: -10.6 and -8.9 on the total anxiety score; -6.5 and -5.7 on the somatic score; and -38.5 and -29.2 for subjectively assessed anxiety. Adverse events were mostly mild or moderate — digestive or psychopathological disorders in 11.5% of participants in the study group and 9.7% in the placebo group.

Homeopathy

A systematic review conducted in 2006 found the evidence for homeopathy in the treatment of anxiety disorders to be inconclusive.119 They examined 8 RCTs and found them to be contradictory but several uncontrolled and observational studies found positive effects and high levels of patient satisfaction. The authors believed more rigorous trials were warranted given the high level of perceived patient satisfaction and current contradictory results.

Physical therapies

Acupuncture

According to traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), acupuncture is effective by removing blockages to the energy (chi) which travels around the body. A blockage in this energy can lead to an imbalance and, therefore disease; acupuncture works by correcting this imbalance. Research is now beginning to emerge which postulates that the physiological explanations behind the clinical benefits of acupuncture may be due to increases of endomorphin-1, beta endorphin, encephalin, serotonin, and dopamine causing analgesia, and sedation.120

In the largest RCT to date, 240 patients diagnosed with anxiety were divided into 3 equal groups and treated accordingly with acupuncture alone, behavioural desensitisation alone, and combined acupuncture and behavioural desensitisation (CABD).121 The cure rates in the acupuncture, behavioural desensitisation and CABD were 20.0%, 26.3% and 52.5%, respectively. The difference in effectiveness of CABD was statistically significant (P<0.01). At 1 year, 60 patients out of the 240 were able to be followed-up and they showed cure rates of 18%, 22% and 48% respectively. That this benefit was largely maintained at 1 year provides a significant rationale for further research into acupuncture for anxiety.

In general, acupuncture is a safe and effective method that can play an important role in managing anxiety associated with difficult to treat conditions such as post-stroke anxiety neurosis where medication side-effect such as sedation can impact on rehabilitation.122

A recent systematic review of the literature identified 12 controlled trials, of which 10 were randomised controlled trials. Four of these randomised controlled trials focused on acupuncture in generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) or anxiety neurosis, while the remaining 6 randomised controlled trials focused on anxiety in the perioperative period.123 Whilst most trials lacked basic methodological details, all trials reported positive findings for acupuncture in the treatment of generalised anxiety disorder or anxiety neurosis, although there is insufficient data for firm conclusions to be drawn. There is limited evidence in favour of auricular acupuncture for peri-operative anxiety.

Aromatherapy

Aromatherapy as a treatment for anxiety has been assessed with most trials using the application of aromatherapy oils through massage. A review of 6 RCTs found that aromatherapy massage had a mild, transient anxiolytic effect, but based on critical assessment of the studies they were unable to recommend aromatherapy as a treatment for anxiety due to inconsistencies in the trials.124 The length of treatments and number of treatments differed between the studies and also the type of aromatherapy oils used, with 2 studies using lavender oil, 2 studies using chamomile oil, 1 study using orange blossom oil, and a further study using an unspecified aroma.

Massage

A recent Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to draw conclusions about the benefits of massage and aromatherapy massage for cancer patients.126 The reviewers included 10 studies, of which 8 were RCTs (357 patients). Most of the studies assessed the effect of massage or aromatherapy massage on anxiety. Four trials (207 patients) measuring anxiety detected a reduction following intervention, with benefits of 19–32% reported. It was not clear if there were any added benefits on anxiety conferred with the addition of aromatherapy. The reviewers concluded massage and aromatherapy massage ‘confer short-term benefits on psychological wellbeing, with the effect on anxiety supported by limited evidence’.125

Reiki/therapeutic touch

A systematic review examining the effectiveness of reiki for any condition conducted in 2008 found 9 randomised clinical trials which met the inclusion criteria.126 They found 2 trials suggested beneficial effects of reiki compared with sham control on depression and 1 trial which examined pain and anxiety reported inter-group differences in favour of reiki having a positive effect when compared with sham control. One further randomised clinical trial which concentrated on examining stress and hopelessness reported positive effects of reiki and distant reiki compared with distant sham control. They also found 2 randomised clinical trials in women undergoing procedures – amniocentesis, or breast biopsy, where reiki did not reduce anxiety associated with the procedure when compared with conventional care.

Anxiety disorders in children

Anxiety disorders in children can be grouped into the same classifications as adults i.e. generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, social anxiety disorder, specific phobias, and specifically separation anxiety. There has been recent research linking the development of anxiety disorders in children with maternal anxiety during pregnancy and post-natal depression. Children with mothers who have suffered post-natal depression appear more likely to develop internalising symptoms of depression and anxiety.127

Cognitive behaviour therapy

A Cochrane review in 2006 found CBT to be an effective treatment for anxiety in children and adolescents.128 Specifically, CBT can be delivered in various formats: individual, group and family/parent and appears effective in just over 50% of cases. They identified 13 studies with 498 subjects and 311 controls involving community or outpatient subjects only, with anxiety of mild to moderate severity. Analyses of the data showed a response rate for remission of any anxiety diagnosis of 56% for CBT versus 28.2% for controls. As an example, in an Australian study surveying the parents of 425 children aged 8 to 11 years, from low income neighbourhoods of Sydney, there were 91 children who demonstrated moderate to severe anxiety symptoms on screening tests.129 These children were then randomised to a school-based 8-session intervention group, called the ‘Cool Kids Program’, or a waitlist control group. The intervention group received CBT, education about anxiety, graduated exposure to fear-related stimuli and social skills training in assertiveness and dealing with teasing. Parents were also offered 2 information sessions. The intervention group reported significant reduction in anxiety symptoms compared with children on the waitlist, even at 4 months follow-up. The effects of the intervention were also confirmed by teacher reports.

Exercise

Exercise for anxiety in children and adolescents was also recently considered in a Cochrane review of 16 studies with a total of 1191 participants (aged 11 and 19 years). They concluded that ‘there appears to be a small effect in favour of exercise in reducing depression and anxiety scores in the general population of children and adolescents’ from a range of clinically diverse studies.130

Humour

A randomised prospective study involving humour for pre-operative anxiety for children and their parents found that an intervention lead by ‘Clown Doctors’ significantly reduced both child and parental anxiety but that the disruption caused by the intervention was such that staff would not have supported the permanent implementation of the intervention.131

Massage, relaxation, bibliotherapy, melatonin

There has been relatively little research into complementary therapies in the treatment of childhood anxiety or situational specific anxiety disorders in children; for example, test anxiety, fear of the dark, anxiety related to medical procedures. A systematic review of the literature conducted in 2008132 concluded that there were few studies of adequate quality that had examined CM in children and adolescents but on the research available there was preliminary evidence that situational-specific anxiety in children could be reduced by massage,133 relaxation training134, 135, melatonin supplements,136 or bibliotherapy137 instructing parents how to deal with anxious children.

Conclusion

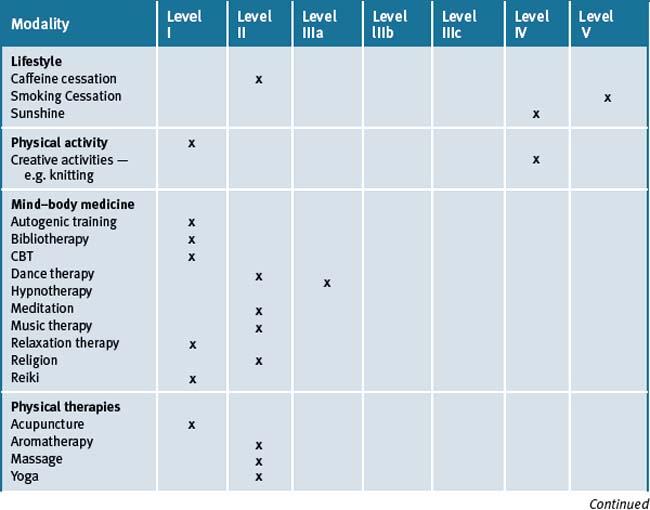

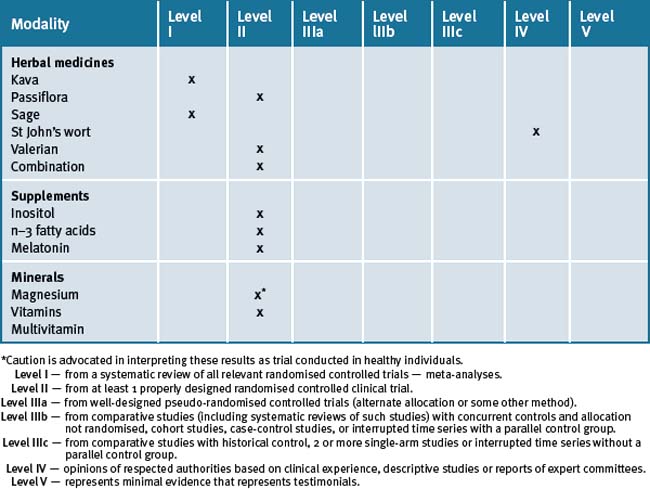

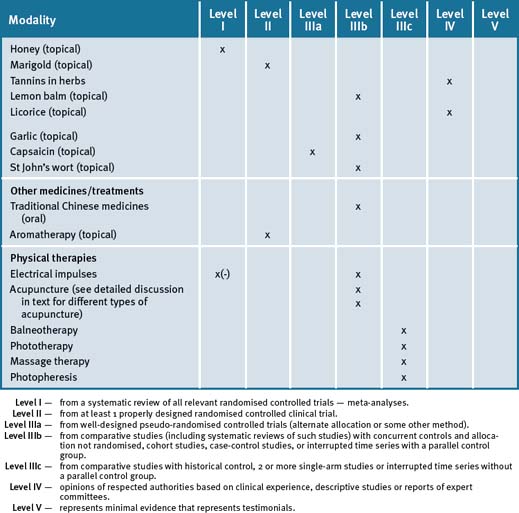

Non-pharmacological therapies can play an important role in the treatment of patients suffering anxiety. They can be used alone in mild-moderate anxiety cases or in combination with pharmaceuticals in severe anxiety. Table 4.2 summarises the current evidence for CM treatments.

Clinical tips handout for patients — anxiety

1 Lifestyle advice

Sleep

2 Physical activity/exercise

3 Mind–body medicine

Rest and stress management

5 Dietary changes

7 Supplements

Fish oils

Inositol

Magnesium and calcium

Vitamin D (cholecalciferol 1000IU)

Doctors should check blood levels and suggest supplementation if levels are low.

Herbal medicine

Kava

St John’s wort

Melatonin

1 Andrews G., Hall W. The mental health of Australians. Canberra: Mental Health branch, Australian government department of health and aged care; 1999.

2 Issakadis C., Andrews G. Service utilization for anxiety in an Australian community sample. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37:153-163.

3 Jorm A.F., Medway J., Christensen H., et al. Public beliefs about the helpfulness of interventions for depression: effects on actions taken when experiencing anxiety and depression symptoms. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34:619-622.

4 The contribution of demographic and morbidity factors to self-reported visit frequency of patients. a cross-sectional study of general practice patients in Australia. BMC Family Practice. 2004;5:17. 7 pages

5 Yates W.R. Phenomenology and epidemiology of panic disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2009 Apr-Jun;21(2):95-102.

6 Bloch S., Singh B. Foundations of Clinical Psychiatry, 3rd edn. Melbourne University Publishing; 2007.

7 Kessler R.C., Davis R.B., Foster D.F., et al. Long-term trends in the use of complementary and alternative medical therapies in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:262-268.

8 Blashki G., Judd F., Piterman L. General practice psychiatry. Sydney: McGraw-Hill; 2007.

9 Egger G., Binns A., Rossner S. Lifestyle Medicine. Sydney: McGraw-Hill; 2008.

10 Kinnersley P., Stott N., Harvey I. The patient-centredness of consultation and outcome in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49:711-716.

11 Holism in Primary Care the views of Scotlands general practitioners. Primary Healthcare Research and Development 2005;6:320–328.

12 Outram S., Murphy B., Cockburn J. The role of GPs in treating psychological distress: a study of midlife Australian women. Family Practice. 2004;21:276-281.

13 Madden S. Managing anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Medicine Today. Update: Anxiety and depression today. 2006. supplement August. Pages 6–10

14 Loerch B., Graf-Morgenstern M., Hautzinger M., et al. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of moclobemide, cognitive-behavioural therapy and their combination in panic disorder with agoraphobia. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;174:205-212. 213–18

15 Orbach G., Linsey S., Grey S. A randomised placebo-controlled trial of a self-help Internet-based intervention for test anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 2006 Jun 29.

16 Taube-Schiff M., Suvak M.K., Antony M.M., et al. Group cohesion in cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social phobia. Behav Res Ther. 2006 Aug 21.

17 Australian and New Zealand clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of panic disorder and agoraphobia. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists Clinical Practice; Guidelines Team for Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;37:641-656. Online. Available: http://www.ranzcp.org/images/stories/ranzcp-attachments/Resources/Publications/CPG/Clinician/CPG_Clinician%20Full_Panic_Disorder_Agoraphobia.pdf (accessed 28-09-09)

18 Buckner J.D., Turner R.J. Social anxiety disorder as a risk factor for alcohol use disorders: a prospective examination of parental and peer influences. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009 Feb 1;100(1-2):128-137. Epub 2008 Nov 20

19 Morris E.P., Stewart S.H., Ham L.S. The relationship between social anxiety disorder and alcohol use disorders: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005 Sep;25(6):734-760.

20 Buckner J.D., Timpano K.R., Zvolensky M.J., et al. Implications of comorbid alcohol dependence among individuals with social anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(12):1028-1037.

21 Buckner J.D., Schmidt N.B. Social anxiety disorder and marijuana use problems: the mediating role of marijuana effect expectancies. Depress Anxiety. 2009 Apr 16. [Epub ahead of print]

22 Buckner J.D., Leen-Feldner E.W., Zvolensky M.J., et al. The interactive effect of anxiety sensitivity and frequency of marijuana use in terms of anxious responding to bodily sensations among youth. Psychiatry Res.. 2009 Apr 30;166(2–3):238-246. Epub 2009 Mar 10

23 Parslow R., Morgan A.J., Allen N.B., et al. Effectiveness of complementary and self-help treatments for anxiety in children and adolescents. Med J Aust. 2008 Mar 17;188(6):355-359.

24 Ernst E., Kanji N. Autogenic training for stress and anxiety: a systematic review. Complement Ther Med. 2000 Jun;8(2):106-110.

25 Stetter F., Kupper S. Autogenic training: a meta-analysis of clinical outcome studies. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2002;27:45-98.

26 Kanji N., White A.R., Ernst E. Autogenic training reduces anxiety after coronary angioplasty:a randomised clinical trial. Am Heart Journal. 2004;147:E10.

27 Goldbeck L., Schmid K. Effectiveness of autogenic relaxation training on children and adolescents with behavioural and emotional problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:1046-1054.

28 Kanji N., White A., Ernst E. Autogenic training to reduce anxiety in nursing students: randomised controlled trial. J Adv Nurs. 2006 Mar;53(6):729-735.

29 Reiner R. Integrating a portable biofeedback device into clinical practice for patients with anxiety disorders: results of a pilot study. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2008 Mar;33(1):55-61. Epub 2008 Feb 20

30 Rice K.M., Blanchard E.B., Purcell M. Biofeedback treatments of generalized anxiety disorder: preliminary results. Biofeedback Self Reg. 1993;18:93-105.

31 Marrs R.W. A meta-analysis of bibliotherapy studies. Am J Community Psychol. 1995;23:843-870.

32 Gould R.A., Clum G.A., Shapiro D. The use of bibliotherapy in the treatment of panic: a preliminary investigation. Behav Ther. 1993;24:241-252.

33 Abramowitz J.S., Moore E.L., Braddock A.E., et al. Self-help cognitive-behavioral therapy with minimal therapist contact for social phobia: a controlled trial. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2009 Mar;40(1):98-105. Epub 2008 Apr 26

34 Shechtman Z., Nir-Shfrir R. The effect of affective bibliotherapy on clients’ functioning in group therapy. Int J Group Psychother. 2008 Jan;58(1):103-117.

35 Jorm A., Christensen H., Griffiths K., et al. Effectiveness of complementary and self-help treatments for anxiety disorders. MJA. 2004 October;181(7):4.

36 Lang E.V., Bentosch E.G., Fick L.J., et al. Adjunctive non-pharmacological analgesia for invasive procedures: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;355:1486-1490.

37 Liossi C., White P., Hatira P. Randomised clinical trial of local anesthetic versus a combination of local anesthetic with self-hypnosis in the management of pediatric procedure-related pain. Health Psychol. 2006 May;25(3):307-315.

38 Saadat H., Drummond-Lewis J., Maranets I., et al. Hypnosis reduces preoperative anxiety in adult patients. Anesth Analg. 2006 May;102(5):1394-1396.

39 Elkins G., White J., Patel P., et al. Hypnosis to manage anxiety and pain associated with colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening: case studies and possible benefits. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2006 Oct;54(4):416-431.

40 Lang E.V., Berbaum K.S., Faintuch S., et al. Adjunctive self-hypnotic relaxation for outpatient medical procedures: A prospective randomised trial with women undergoing large core breast biopsy. Pain. 2006 Sep 5. [Epub ahead of print]

41 Gholamrezaei A., Ardestani S.K., Emami M.H. Where does hypnotherapy stand in the management of irritable bowel syndrome? A systematic review. J Altern Complement Med. 2006 Jul-Aug;12(6):517-527.

42 Huynh M.E., Vandvik I.H., Diseth T.H. Hypnotherapy in child psychiatry: the state of the art. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008 Jul;13(3):377-393.

43 Aviv A. Tele-hypnosis in the treatment of adolescent school refusal. Am J Clin Hypn. 2006 Jul;49(1):31-40.

44 Weisberg M.B. 50 years of hypnosis in medicine and clinical health psychology: a synthesis of cultural crosscurrents. Am J Clin Hypn. 2008 Jul;51(1):13-27.

45 Fern P.A. Hypnosis to alleviate perioperative anxiety and stress: a journey to challenge ideas. J Perioper Pract. 2008 Jan;18(1):14-16.

46 Krisanaprakornkit T., et al. Meditation therapy for anxiety disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 3):2006.

47 Ernst E., Pittler M.H., Wider B., et al. Mind body therapies: are the trial data getting stronger? Altern Ther Health Med. 2007 Sep-Oct;13(5):62-64.

48 Manzoni G.M., Pagnini F., Castelnuovo G., et al. Relaxation training for anxiety: a ten-years systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2008 Jun 2;8:41.

49 Cooke M., Chaboyer W., Sculter P., et al. The effect of music on preoperative anxiety in day surgery. Journal Advanced Nursing. 2005 Oct;52(1):47-55.

50 Sendelbach S.E., Halm M.A., Doran K.A., et al. Effects of music therapy on physiological and psychological outcomes for patients undergoing cardiac surgery. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006 May-Jun;21(3):194-200.

51 Gallagher L.M., Lagman R., Walsh D., et al. The clinical effects of music therapy in palliative medicine. Support Care Cancer. 2006 Aug;14(8):859-866.

52 Whitehead-Pleaux AM, Baryza MJ, Sheridan RL. The effects of music therapy on pediatric patients’ pain and anxiety during donor site dressing change. J Music Ther 2006 Summer;43(2):136–53.

53 Hummer R., Rogers R., Nam C., et al. Religious involvement and U.S. adult mortality. Demography. 1999;36(2):273-285.

54 Razali S.M., Hasanah C.I., Aminah K., et al. Religious sociocultural psychotherapy in patients with anxiety and depression. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1998;32:867-872.

55 Clave-Brule M., Mazloum A., Park R.J., et al. Managing anxiety in eating disorders with knitting. Eat Weight Disord. 2009 Mar;14(1):e1-e5.

56 Irwin M.R., Cole J.C., Nicassio P.M. Comparative meta-analysis of behaviorual interventions for insomnia and their efficacy in middle-aged adults and older adults 55+ years. Health Psychol. 2006 Jan;25(1):3-14.

57 Ernst E., Pittler M.H., Wider B., et al. Mind body therapies: are the trial data getting stronger? Altern Ther Health Med. 2007 Sep-Oct;13(5):62-64.

58 Steiger A. Sleep and endocrinology. J Intern Med. 2003;254(1):13-22.

59 Ramsawh H.J., Stein M.B., Belik S.L., et al. Relationship of anxiety disorders, sleep quality and functional impairment. J Psychiatr Res. 2009 Mar:6.

60 Olde Rikert M.G., Rigaud A.S. Melatonin in elderly patients with insomnia. A systematic review. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2001;34:491-497.

61 Ismail S.A., Mowafi H.A. Melatonin provides anxiolysis, enhances analgesia, decreases intraocular pressure, and promotes better operating conditions during cataract surgery under topical anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2009 Apr;108(4):1146-1151.

62 Mowafi H.A., Ismail S.A. Melatonin improves tourniquet tolerance and enhances postoperative analgesia in patients receiving intravenous regional anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2008 Oct;107(4):1422-1426.

63 Caumo W., Levandovski R., Hidalgo M.P. Preoperative anxiolytic effect of melatonin and clonidine on postoperative pain and morphine consumption in patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study. J Pain. 2009 Jan;10(1):100-108. Epub 2008 Nov 17

64 Garzón C., Guerrero J.M., Aramburu O., et al. Effect of melatonin administration on sleep, behavioral disorders and hypnotic drug discontinuation in the elderly: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2009 Feb;21(1):38-42.

65 Cheuk DK, Yeung WF, Chung KF, et al. Acupuncture for insomnia Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007 Jul 18;(3):CD005472.

66 Armstrong D.J., Meenagh G.K., Bickle I., et al. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with anxiety and depression in fibromyalgia. Clin Rheumatol. 2007 Apr;26(4):551-554. Epub 2006 Jul 19

67 Cherniack E.P., Troen B.R., Florez H.J., et al. Some new food for thought: the role of vitamin D in the mental health of older adults. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009 Feb;11(1):12-19.

68 West R., Hajek P. What happens to anxiety levels on giving up smoking? Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1589-1592.

69 Wipfli B.M., Rethorst C.D., Landers D.M. The anxiolytic effects of exercise: a meta-analysis of randomised trials and dose-response analysis. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2008 Aug;30(4):392-410.

70 DeMoor M.H., Boomsma D.I., Stubbe J.H., et. al. Testing causality in the association between regular exercise and symptoms of anxiety and depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. August 2008;65(8):897-905.

71 Broocks A., Bandelow B., Pekrun G., et al. Comparison of aerobic, clomipramine and placebo in the treatment of placebo of panic disorder. Am J Psychiatr. 1998;155:603-609.

72 Rao R., Raghuram R., Nagendra H.R., et al. Anxiolytic effects of a yoga program in early breast cancer patients undergoing conventional treatment: a randomised controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2009 Jan;17(1):1-8. Epub 2008 Oct 14

73 Sahasi G., Mohan D., Kakcer C. Effectiveness of yogic techniques in the management of anxiety. J Personality Clin Stud. 1989;5:51-55.

74 Kushner M.G., Mackenzie T.B., Fiszdon J., et al. The effects of alcohol consumption on laboratory-induced panic and state anxiety. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:264-270.

75 Abrams K., Kushner M.G., Medina K.L., et al. The pharmacologic and expectancy effects of alcohol on social anxiety in individuals with social phobia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;64:219-231.

76 MacDonald A.B., Stewart S.H., Hutson R., et al. The roles of alcohol and alcohol expectancy in the dampening of responses to hyperventilation among high anxiety sensitive young adults. Addict Behav. 2001;26:841-867.

77 Kushner M.G., Abrams K., Borchardt C. The relationship between anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders: a review of major perspectives and findings. Clin Psychol Rev. 2000;20:149-171.

78 Driessen M., Meier S., Hill A., et al. The course of anxiety, depression and drinking behaviours after completed detoxification in alcoholics with and without comorbid anxiety and depressive disorders. Alcohol. 2001;36:249-255.

79 Kendler K.S., Myers J. O Gardner C. Caffeine intake, toxicity and dependence and lifetime risk for psychiatric and substance use disorders: an epidemiologic and co-twin control analysis. Psychol Med. 2006 Aug 8:1-9.

80 Hewlett P., Smith A. Correlates of daily caffeine consumption. Appetite. 2006 Jan;46(1):97-99.

81 Bruce M.S., Lader M. Caffeine abstention in the management of anxiety disorders. Psychol Med. 1989;19:211-214.

82 Totten G.L., France C.R. Physiological and subjective anxiety responses to caffeine and stress in nonclinical panic. J Anxiety Disord. 1995;9:473-488.

83 Tancer M.E., Stein M.B., Uhde T.W. Lactic acid response to caffeine in panic disorders: comparison of social phobics and normal controls. Anxiety. 1994–95;1:138-140.

84 Uhde T.W., Boulenger J.P., Jimerson D.C., et al. Caffeine: relationship to human anxiety, plasma MHPG and cortisol. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1984;20:426-430.

85 Boulenger J.P., Uhde T.W., Wolff E.A., et al. Increased sensitivity to caffeine in patients with panic disorders: preliminary evidence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41:1067-1071.

86 Smith G.A. Caffeine reduction as an adjunct to anxiety management. Br J Clin Psychol. 1988;27:265-266.

87 Fontani G., et al. Cognitive and physiological effects of Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation in healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Invest. 2005 Nov;35(11):691-699.

88 Yehuda S., Rabinovitz S., Mostofsky D.I. Mixture of essential fatty acids lowers test anxiety. Nutr Neurosci. 2005 Aug;8(4):265-267.

89 Green P., Hermesh H., Monselise A., et al. Red cell membrane omega-3 fatty acids are decreased in nondepressed patients with social anxiety disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006 Feb;16(2):107-113.

90 Buydens-Branchy L., Branchy M., Hibbeln J.R. Associations between increases in plasma n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids following supplementation and decreases in anger and anxiety in substance abusers. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008 Feb 15;32(2):568-575. Epub 2007 No7

91 Appleton K.M., Rogers P.J., Ness A.R. Is there a role for n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in the regulation of mood and behaviour? A review of the evidence to date from epidemiological studies, clinical studies and intervention trials. Nutr Res Rev. 2008 Jun;21(1):13-41.

92 Benjamin J., Levine J., Fux M., et al. Double-blind, controlled crossover trial of inositol treatment for panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1084-1086.

93 Palatnik A., Frolov K., Fux M., et al. Double-blind, controlled cross-over trial of inositol versus fluvoxamine for the treatment of panic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21:335-339.

94 Kaplan Z., Amir M., Swartz M., et al. Inositol treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Anxiety. 1996;2:51-52.

95 Fux Levine J, Aviv A., et al. Inositol treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1219-1221.

96 Fux M., Benjamin J., Belmaker R.H. Inositol versus placebo augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitor in the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: a double blind cross-over study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999;2:193-195.

97 Kriv G.K., Tsachev K.N. Magnesium, schizophrenia and manic-depressive disease. Neuropsychobiology. 1990;23:79-81.

98 Bockova E., Hronek J., Kolomaznik M., et al. Potentiation of the effects of anxiolytics with magnesium salts. Cesk Psychiatr. 1992;88:141-144.

99 De Souza MC, Walker AF, Robinson PA, et al. Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2006 Issue 3 Copyright © 2006. The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. De Souza MC, Walker AF, Robinson PA, Bolland K.

100 De Souza M.C., Walker A.F., Robinson P.A., et al. A synergistic effect of a daily supplement for 1 month of 200mg magnesium plus 50mg vitamin B6 for the relief of anxiety-related premenstrual symptoms: a randomised, double-blind, crossover study. Journal of Women’s Health & Gender-based Medicine. 2000 Mar;9(2):131-139.

101 Carroll D., Ring C., Suter M., et al. The effects of an oral multivitamin combination with calcium, magnesium and zinc on psychological well-being in healthy young male volunteers: a double blind placebo-controlled trial. Psychopahrmacologica. 2000;150:220-225.

102 Ernst E. Herbal remedies for anxiety – a systematic review of controlled clinical trials. Phytomedicine. 2006 Feb;13(3):205-208.

103 Pittler M.H., Ernst E. Kava extract versus placebo for treating anxiety. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 3):2006.

104 Therapeutic Goods Administration, Australia. Online. Available website http://www.tga.gov.au/cm/kavafs0504.htm (accessed 28-09-09)

105 Kennedy D.O., Pace S., Haskell, et al. Effects of Cholinesterase Inhibiting Sage (Salvia officinalis) on Mood, Anxiety and Performance on a Psychological Stressor Battery. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:845-852.

106 Davidson Jonathan R.T., Connor Kathryn M. Letters To The Editors: St. John’s Wort in Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Three Case Reports. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001 December;21(6):635-636.

107 Linde K, Berner MM, Kriston L. St John’s wort for major depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD000448. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000448.pub3

108 Ernst E. Herbal remedies for depression and anxiety. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2007;13:312-316.

109 Taibi D.M., Landis C.A., Petry H., et al. A systematic review of valerian as a sleep aid: safe but not effective. Sleep Med Rev. 2007 Jun;11(3):209-230.

110 Miyasaka L.S., Atallah A.N., Soares B.G.O. Valerian for anxiety disorders. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 4):2006.

111 Garges H.P., Varia I., Doraiswarmy P.M. Cardiac Complications and Delirium Associated with Valerian Root Withdrawal. JAMA. 1998;280:1566-1567.

112 Akhondzadeh S., Naghavi H.R., Vazirian M., et al. Passionflower in the treatment of generalized anxiety: a pilot double-blind randomised controlled trial with oxazepam. J.Clin Pharm Ther. 2001;26:363-367.

113 Takagi K., Saito H., Tsychiya M. Pharmacological Studies of Panax Ginseng Root: Pharmacological properties of a Crude Saponin Fraction. Japanese Journal of Pharmacology. 1972;2:3339-3346.

114 Wong A.H.C., Smith M., Boon H.S. Herbal remedies in psychiatric practice. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1998;55:1033-1044.

115 Kennedy D.O., et al. Attenuation of laborotary-induced stress in humans after acute administration of Melissa officinalis (Lemon Balm). Psychosom Med. 2004;66:607-613.

116 Adreatini R., Sartori V.A., Seabra M.L., et al. Effect of valepotriates (valerian extract) in generalized anxiety disorder: a randomised placebo-controlled pilot study. Phytother Res. 2002;16:650-654.

117 Houghton P.J. The Scientific Basis for Reputed Activity of Valerian. Journal of Pharmacology. 1999;5:505-512.

118 Hanus M., Lafon J., Mathieu M. Double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a fixed combination containing two plant extracts (Crataegus oxyacantha and Eschscholtzia californica) and magnesium in mild-to-moderate anxiety disorders. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004 Jan;20(1):63-71.

119 Pilkington K., Kirkwood G., Rampes H., et al. Homeopathy for anxiety and anxiety disorders: a systematic review of the research. Homeopathy. 2006 Jul;95(3):151-162.

120 Cabyoglu M.T., Ergene N., Tan U. The mechanism of acupuncture and clinical applications. Int J Neurosci. 2006 Feb;116(2):115-125.

121 Guizhen L., Yunjun Z., Linxiang G., et al. Comparative study on acupuncture combined with behavioural desensitisation for treatment of anxiety neuroses. Am J Acupunct. 1998;26:117-120.

122 Wu P., Liu S. Clinical observation on post-stroke anxiety neurosis treated by acupuncture J Tradit Chin Med. 2008 Sep;28(3):186-188.

123 Pilkington K., Kirkwood G., Rampes H., et al. Acupuncture for anxiety and anxiety disorders–a systematic literature review. Acupunct Med. 2007 Jun;25(1–2):1-10.

124 Ernst E., Cooke B. Aromatherapy: a systematic review. British Journal of General Practice. 493, 2000 June.

125 Fellowes D., Barnes K., Wilkinson S. Aromatherapy and massage for symptom relief in patients with cancer. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 3):2006.

126 Lee M.S., Pittler M.H., Ernst E. Effects of reiki in clinical practice: a systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Int J Clin Pract. 2008 Jun;62(6):947-954. Epub 2008 Apr 10

127 Essex M.J., Klein M.H., Miech R., et al. Timing of exposure to maternal major depression and children’s mental health symptoms in kindergarten. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:151-156.

128 James A., Soler A., Weatherall R. Cognitive behaviour therapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 3):2006.

129 Mifsud C., Rapee R.M. Early intervention for childhood anxiety in a school setting: outcomes for an economically disadvantaged population. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:996-1004.

130 Larun L., Nordheim L.V., Ekeland E., et al. Exercise in prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression among children and young people. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 3):2006.

131 Vagnoli L., et al. Clown Doctors as a Treatment for Preoperative Anxiety in Children: A Randomised, Prospective Study. Pediatrics. 2005 October;116(4):e563-e567.

132 Parslow R., Morgan A., Allen N., et al. Effectiveness of complementary and self-help treatments for anxiety in children and adolescents. MJA. 2008;188(6):355-359.

133 Field T., Seligman S., Scafadi F., et al. Alleviating post-traumatic in children following Hurricane Andrew. J Appl Dev Psychol. 1996;17:37-50.

134 Smead R. A comparison of counsellor administered and tape-recorded relaxation training on decreasing target and non-target anxiety in elementary school children. Diss Abstr Int B. 1981;42:1015-1016.

135 Roque G.M. A comparative evaluation of two relaxation strategies with school-aged children. Diss Abstr Int B. 1992;53:3165.

136 Samarkandi A., Naguib M., Riad W., et al. Melatonin vs midazolam premedication in children: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2005;22:189-196.

137 Rapee R.M., Abbott M.J., Lyneham H.J. Bibliography for children with anxiety disorders using written materials for parents: a randomised controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:436-444.