182 Antipsychotics

Pharmacology of Antipsychotics

Pharmacology of Antipsychotics

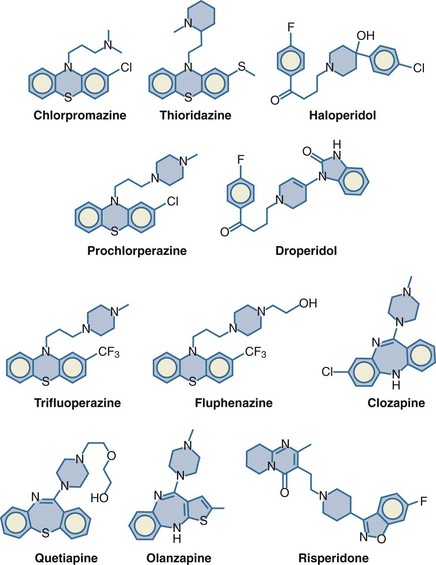

The antipsychotics can be divided into three categories based on their chemical structure and receptor-binding activities: phenothiazines, butyrophenones, and atypical antipsychotics. The prototypical antipsychotic agent in the phenothiazine class is chlorpromazine (Thorazine). Its pharmacology is discussed in detail in this chapter and then compared with that of the newer antipsychotic agents.1 The structures of some commonly used antipsychotics are shown in Figure 182-1.

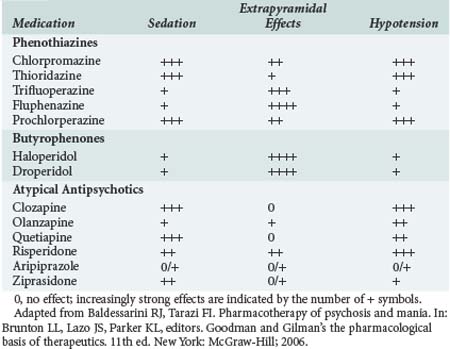

In terms of the number of neurotransmitter systems with which it interacts, chlorpromazine is one of the “dirtiest” drugs in pharmacology. It is a competitive antagonist at the dopamine (D2), muscarinic, cholinergic, histamine (H1), α-adrenoceptor, and serotonin (5-HT2) receptors. It is believed that its primary antipsychotic effect results from dopaminergic blockade, whereas many (but certainly not all) of its adverse effects result from blockade of cholinergic (sedation, dry mouth) and α-adrenoceptor (orthostatic hypotension) receptors. The relative propensities of some of the antipsychotics to cause sedation, extrapyramidal effects, and hypotension are listed in Table 182-1.

Haloperidol (Haldol) is in the butyrophenone class. It causes little sedation or hypotension and has high incidence of extrapyramidal effects. Because of its decreased propensity to cause hypotension, especially in hypovolemic patients, haloperidol is the most commonly used antipsychotic in the ICU for the management of delirium or agitation (see Chapter 2). Droperidol (Inapsine) is pharmacologically very similar to haloperidol and is commonly used by anesthesiologists as an antiemetic.

Use of Antipsychotics in the Intensive Care Unit

Use of Antipsychotics in the Intensive Care Unit

The most common indication for use of antipsychotic medications in the ICU is for treatment of agitation or delirium. Haloperidol is the usual drug of choice for this indication because of intensivists’ familiarity with it and because of its substantial safety record.2

If the need to begin treatment is not urgent, and if gastrointestinal absorption is expected to be reliable, oral haloperidol may be used at a beginning dose of 0.5 to 1 mg and repeated as needed. As the duration of therapy increases, the interval between doses also increases because the terminal half-life of haloperidol is about 1 day in normal persons and may be prolonged in critically ill persons. In the urgent management of severe agitation, the IV (or less desirably, the IM) route may be used. A reasonable starting dose is 2.5 to 5 mg; if an inadequate response is obtained, additional escalating doses (e.g., twice the previously administered dose) may be given every 5 to 10 minutes. Once reasonable efficacy has been achieved, the last administered dose may then be repeated every 4 to 6 hours. Some critically ill patients require hundreds of milligrams daily for the management of agitation or delirium. One alternative to frequent administration of bolus injections of haloperidol is administration of haloperidol by continuous infusion. This method may provide better control of delirium and agitation in some patients and decrease the nursing effort required to prevent self-inflicted injuries.3 After steady-state blood concentrations of haloperidol are approached, days are required for the effects to wane after stopping administration.

Olanzapine recently has been studied in comparison with haloperidol for treatment of delirium in the ICU.2 Overall efficacy was comparable with either medication, and there were fewer extrapyramidal effects with olanzapine.

Management Of Adverse Effects

For treatment of extrapyramidal effects caused by an antipsychotic drug, a centrally acting anticholinergic is given, usually IV. The usual doses are 1 to 2 mg of benztropine (Cogentin) or 25 to 50 mg of diphenhydramine (Benadryl). Diphenhydramine causes more sedation than benztropine, which may or may not be advantageous in a particular patient. Because the extrapyramidal effects are dose related, decreasing the subsequent dose may lessen the likelihood of recurrence. Alternatively, changing to a different medication with fewer inherent extrapyramidal effects is also an option (see Table 182-1). However, such a change in therapy is likely to result in greater hypotensive effects from the antipsychotic medication, a factor that must be considered in critically ill patients.

Treatment requires supportive measures such as cessation of the antipsychotic medication, active cooling, and maintenance of blood pressure and urine output. The efficacy of additional pharmacologic therapy is controversial.4 The dopaminergic agonists, amantadine (Symmetrel) and bromocriptine (Parlodel), and dantrolene (Dantrium), a muscle relaxant with an intracellular mechanism of action that is also used to treat malignant hyperthermia, are commonly administered. However, it is unclear whether these agents convey benefits beyond supportive therapy.

Most phenothiazine and butyrophenone antipsychotics are thought to increase the incidence of torsades de pointes, a form of ventricular tachycardia that can deteriorate into ventricular fibrillation.5 Cases of torsades de pointes have also been ascribed to therapy with atypical antipsychotics, although the incidence is much lower. Torsades de pointes is usually, but not always, preceded by an increase in the corrected QT interval (QTc) on the electrocardiogram (ECG). QTc prolongation is a known dose-related effect and is common during therapy with thioridazine, chlorpromazine, haloperidol, and droperidol. Torsades de pointes is more likely when the QTc is lengthened beyond 500 msec or when it is prolonged 60 msec or more beyond its usual baseline value. Discontinuation of the antipsychotic agent decreases QTc and the associated risk of torsades de pointes.

The seizure threshold may be lowered by antipsychotic medications, especially chlorpromazine and clozapine.6 However, because the effect is dose dependent, large doses of other antipsychotics also have been associated with seizures, both in persons with a known preexisting seizure disorder and in persons with no prior history. The approach to treatment of an antipsychotic-related seizure is similar to that used with other drug-induced or idiopathic seizures: initial measures to maintain airway patency, along with administration of supplemental oxygen, an anticonvulsant medication (e.g., diazepam [Valium]) if the seizure does not terminate spontaneously, and withdrawal or decrease in the dose of the offending medication (if known).

Management of Antipsychotic Overdose

Management of Antipsychotic Overdose

Patients may accidentally or deliberately administer an overdose of an antipsychotic, either alone or in combination with other medications or alcohol. Such patients may require admission to an ICU. In contrast to other classes of medications that are active in the CNS (e.g., tricyclic antidepressants, barbiturates, opioids), all of the antipsychotics have a high therapeutic index (in terms of lethality), and deaths due to overdose are quite rare.7 When deaths have occurred after overdoses in persons who were found alive and transported to a hospital, the most common cause has been aspiration pneumonitis.

Key Points

Baldessarini RJ, Tarazi FI. Pharmacotherapy of psychosis and mania. In Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL, editors: Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics, 11th ed, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2006.

Burns MJ. The pharmacology and toxicology of atypical antipsychotic agents. Clin Toxicol. 2001;39:1-14.

Morandi A, Jackson JC, Ely EW. Delirium in the intensive care unit. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21:43-58.

Smith FA, Wittmann CW, Stern TA. Medical complications of psychiatric treatment. Crit Care Clin. 2008;24:635-656.

1 Baldessarini RJ, Tarazi FI. Pharmacotherapy of psychosis and mania. In Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL, editors: Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics, 11th ed, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2006.

2 Morandi A, Jackson JC, Ely EW. Delirium in the intensive care unit. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21:43-58.

3 Riker RR, Fraser GL, Cox PM. Continuous infusion of haloperidol controls agitation in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 1994;22:433-440.

4 Smith FA, Wittmann CW, Stern TA. Medical complications of psychiatric treatment. Crit Care Clin. 2008;24:635-656.

5 Haddad PM, Anderson IM. Antipsychotic-related QTc prolongation, torsades de pointes and sudden death. Drugs. 2002;62:1649-1671.

6 Pisani F, Oteri G, Costa C, et al. Effects of psychotropic drugs on seizure threshold. Drug Saf. 2002;25:91-110.

7 Burns MJ. The pharmacology and toxicology of atypical antipsychotic agents. Clin Toxicol. 2001;39:1-14.