Anticoagulation and thrombolytic therapy

Anticoagulation

Unfractionated heparin

Standard unfractionated heparin may be used therapeutically to treat established thrombosis (usually intravenously at higher dosage) or prophylactically to prevent thrombosis (usually subcutaneously at lower dosage). Most common indications for therapeutic use are deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) (Fig 40.1). A typical regimen is an intravenous loading dose of 5000 units followed by an infusion of 1000–2000 units/hour. The anticoagulant response varies as the drug binds non-specifically to plasma and cellular proteins. Laboratory monitoring using the APTT (see p. 20) is required; the therapeutic range is usually 1.5–2.5, these values being the ratio of the patient’s APTT to a control sample. As the half-life is short, high APTTs are managed by stopping the heparin but in the event of bleeding (in up to 7% of cases) the antidote protamine can be given. When the APTT is too low the heparin dose should be promptly increased. Heparin is normally continued until oral anticoagulation is therapeutic.

Warfarin

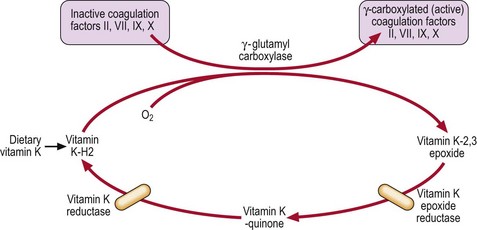

Oral anticoagulant drugs are derived from 4-hydroxycoumarin and the standard agent is warfarin. Warfarin works by antagonising vitamin K, which is needed for the gamma carboxylation of certain glutamic acid residues that facilitate calcium binding of coagulation factors II, VII, IX and X (Fig 40.2).

Fig 40.2 The vitamin K cycle and the action of warfarin.

The major site of warfarin action is not a direct effect on the carboxylation step needed for coagulation factor activation but on steps needed for resynthesis of active vitamin K from its epoxide form.

Some indications for warfarin are shown in Table 40.1. Where rapid anticoagulation is required a reasonable starting regimen is a single 10 mg dose and then protocol-guided adjustment according to the international normalised ratio (INR). A coagulation screen should always be checked before warfarin is prescribed. The maintenance dose is usually between 3 and 9 mg. Laboratory monitoring depends on the prothrombin time (see p. 20). As thromboplastin reagents used in this test vary, their sensitivity is labelled with an international sensitivity index (ISI) which permits reporting as an INR such that INR = (prothrombin time)ISI.

Table 40.1

Warfarin: common indications and recommended INRs

| Indication | Target INR1 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 2.5 |

| Pulmonary embolus | 2.5 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2.5 |

| Mural thrombosis | 2.5 |

| Cardioversion | 2.5 |

| Mechanical prosthetic heart valves | 2.5–3.52 |

| Recurrent venous thromboembolism on warfarin therapy | 3.5 |

| Thrombosis in antiphospholipid antibody syndrome | 2.5 |

1An INR within 0.5 units of the target is usually satisfactory.

As it takes several days for warfarin to become therapeutic, the conventional treatment of established thrombosis is to start heparin and warfarin simultaneously and only to stop heparin when the desired INR has been achieved. Warfarin should be used with caution in patients with a bleeding tendency. The most common side-effect is haemorrhage, the risk of serious bleeding correlating with the height of the INR. Poor control of anticoagulation and bleeding may arise from poor prescribing or compliance, intercurrent illness and interaction with a potentiating drug (Table 40.2). A prolonged INR in a non-haemorrhagic patient may only require withdrawal of the drug for a few days. Where there is haemorrhage, warfarin can be reversed within hours by oral/intravenous vitamin K (0.5–5 mg) and instantly by infusion of a concentrate of prothrombin complex. Guidelines are complex and significant warfarin overdosage should be discussed with a haematologist. The duration of warfarin treatment depends on the indication. Anticoagulation may be needed for only 3 months in a patient with a limited DVT and reversible risk factors (e.g. post-surgery). Longer periods are indicated in idiopathic venous thrombosis, and lifelong warfarin treatment may be justified following recurrent episodes of venous thrombosis or where there is a known ongoing thrombotic risk such as a prosthetic heart valve, atrial fibrillation or a thrombophilic state.

Table 40.2

Drugs interacting with warfarin1

| Potentiating | Antagonising |

| Alcohol | Oral contraceptives |

| Cimetidine | Spironolactone |

| Allopurinol | Antihistamines |

| Quinine | Barbiturates |

| Amiodarone | Rifampicin |

| Co-trimoxazole | Sucralfate |

| Metronidazole | Anti-epileptics |

| Tricyclics | |

| Aspirin and salicylates | |

| Anabolic steroids | |

| Thyroxine | |

| Sulfinpyrazone |

1These are some commonly implicated agents – this is not a comprehensive list.

Thrombolytic therapy

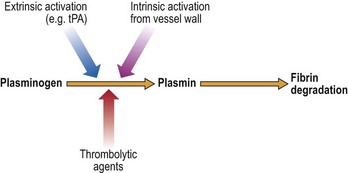

Thrombolytic agents dissolve fresh clots and therefore restore vascular patency more quickly than anticoagulants. The commonly used agents – streptokinase, urokinase and tissue plasminogen activator (alteplase) – work by activating the fibrinolytic system (see p. 13 and Fig 40.3). They convert plasminogen, the inactive proenzyme of the system, to the proteolytic enzyme plasmin. Thrombolytic drugs are indicated in any patient with acute myocardial infarction in which the benefit is likely to outweigh the risk of treatment. Early administration gives the best results. Other possible uses for this class of drugs include treatment of complicated venous thrombosis, acute ischaemic stroke and the unblocking of occluded venous catheters. The major side-effect is excessive bleeding.