5 Anticipatory Grief and Bereavement

I didn’t know what ‘metachromatic leukodystrophy’ meant. I asked for an explanation and when they told us it was something to do with his brain I just kind of panicked and freaked out… His mental abilities are going to be changing and I think having the mental aspect going in his life is going to be a big situation in our lives… When he’s not going to acknowledge or know who we are is going to be a big issue. [tears]. We know he’s going to die and his life expectancy is a lot shorter, which makes it very hard. I’m not ready for that. I don’t think I’ll ever be ready for that but I’m going to do my best.1

Imagine—I was only eight years old when my brother died! Now I have to live with this for the rest of my life.2

When my son died, visitors offering their condolences, thinking to comfort me, said: ‘Life goes on.’ What nonsense, I thought, of course it doesn’t. It’s death that goes on. My child is dead now and will be dead tomorrow and next year and forever. There’s no end to that. But perhaps there will be an end to the sorrow of it. Sorrow has rushed over the world like the waters of the Deluge, and it will take time to recede.3

Anticipatory grief and bereavement—the before and after of loss—comprise physical, psychological, spiritual, social, and cultural facets. Webster’s Dictionary defines “bereaved” as “a word derived from ‘reaved’ or ‘reft’ meaning: to deprive and make desolate, especially by death”4 (Fig. 5-1). Bereavement is a process that ebbs and flows over a lifetime. At its core is the child, surrounded by concentric circles of family, friends, members of the professional team, and the wider community and culture.

Fig. 5-1 A heart weeping.

(Reprinted from Sourkes, B. et al. Food, toys, and love: pediatric palliative care. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 35(9): 345–392, 2005.)

Over the past decade of research, the perspectives of bereaved parents have proved to be an invaluable resource for the development of pediatric palliative care.5–7 Such research has explored the care provided to the child and family throughout the illness and into bereavement, rather than an exclusive focus on the loss itself.8–9 Approaching bereaved families for research purposes had been questioned in terms of the risk of inflicting psychological harm or distress.10 Yet several studies have shown that parents find participation to be a positive and therapeutic experience—more so than non-bereaved parents.11–13

This chapter focuses on the interplay between the universality of the grief experience and the uniqueness of each individual and family’s response. The phenomenon of anticipatory grief in the family is described, followed by a discussion of bereavement (Box 5-1). Particular emphasis is on the role of assessment in bereaved families and the implications for intervention, including cultural and spiritual dimensions. Clinical vignettes of bereaved families highlight the themes of the chapter. The grief of the palliative care clinicians who care for these children and families is also addressed.

BOX 5-1 Anticipatory Grief and Bereavement: Key Concepts

Anticipatory Grief

Bereavement

The Family Unit

In modern times, the definition of family has expanded to encompass many diverse constellations. From the outset, a family’s own definition of their family unit and the role of each member should be elicited. Without such information, clinicians’ assumptions of inclusion or exclusion may be faulty, and valuable sources of support overlooked. The nuclear family of child, siblings, and parents is at the core, surrounded by the extended family. In particular, grandparents frequently play a major role. Close friends may be indistinguishable from family, especially in palliative care situations. With the changing structure of the family, latitude must be made for alternative and complicated arrangements. These include divorced and reconstituted (blended) families, with their inherently conflicted histories and new alliances; single-parent families; and children of gay parents.14 The composition of the family frames many other factors, including developmental level; psychological history, particularly coping with past losses and trauma; sources of support; and cultural and spiritual beliefs.

The developmental level of the family unit is frequently a salient dimension in the impact of a child’s illness and death.15–18 Young parents are often just learning how to incorporate children into their relationship as they begin to expand their definition of family. The premature death of a young child can send parents reeling into uncertainty about their identity: Are they still parents? Are they still a family? Furthermore, with little prior experience of negotiating loss or death as a couple, they may experience confusion and fear about each other’s reactions. These families often need more structured guidance than an older family that has already negotiated previous losses.

A universal phenomenon in the bereavement process is that individuals in the same family grieve in different ways and on different schedules.15–18 Despite mourning the same child, family members are often out of sync with one another in their experience and expressions of grief. Misunderstanding, guilt, anger, and resentment, and a profound loneliness, often arise when this phenomenon is not understood.

It is crucial to recognize the impact of background, culture, and language on the family’s experience of the child’s illness and treatment, how they make decisions along the way, and on the grief process.19 Cultural perceptions may challenge the use of language. For instance, in English, compassion connotes a deep caring. In some Spanish traditions, however, the word is primarily connoted with care for the dying. Thus, compassion may communicate an unintended message to the family. Deepening the awareness of such nuances and differences enables bereavement care to begin where the family is cuturally.

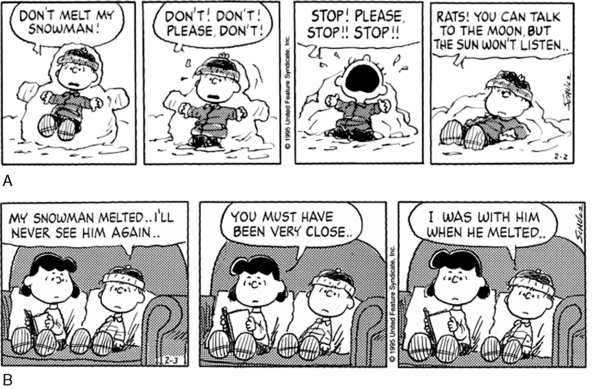

As for children, their modes of expressing grief may differ substantially from adults’ and thus their grief’s meaning and depth are often underestimated or even missed completely (Fig. 5-2). All too often, siblings become disenfranchised grievers,20 their loss is minimized compared to that of their parents’. They are often admonished to be strong for their parents with little acknowledgment of their own mourning process.2

Current Research

Parents

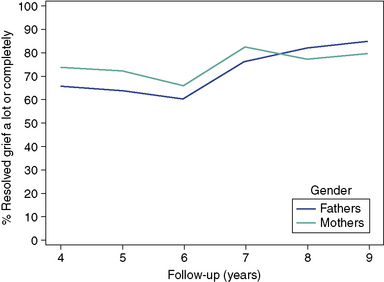

The loss of a child is described as one of the most stressful life events possible.21 The grief is more intense and longer lasting than that following any other type of loss.22 Some studies suggest it may take at least four to six years to “work through” the death of a child23 (Fig. 5-3). The loss itself is compounded when parents have witnessed their child’s protracted physical and emotional suffering throughout the illness.24–26 Despite the traumatic nature of the experience, and the fact that bereaved parents are at increased risk of physical and psychological morbidity,27–29 most individuals are able to come to terms with the loss over time. Two types of factors have been studied for their impact on bereavement outcome in parents: those that can be managed (modified or avoided) in the current health care setting, and those that cannot.

Factors that lie beyond the scope of the healthcare setting include a family’s history of previous losses, pre-morbid conditions, and financial problems. Even the age and gender of the child has been found to affect parental bereavement outcome.27,30,31 For fathers, the risk of anxiety and depression is greater after the death of a child older than 8, nearly twice as high as those fathers whose younger child died.27 No such relationship to the child’s age is seen in mothers. Gender of the child also affects mothers and fathers differently. The risk of morbidity in mothers is higher when a daughter dies.31 Although such factors are not changeable, it is extremely important for clinicians to be aware of them in their daily work with families.

Factors that can be modified within the healthcare setting are all related to the quality of palliative care. For example, the absence of clinicians at the moment of a child’s death increases the likelihood of parents reporting unrelieved pain, as well as an intensely difficult death.8 Location of the child’s death is another factor in bereaved parents’ morbidity: fathers are less likely to suffer from depression if the child dies at home.32 It must still be determined whether the significant factor is the actual location of the child’s death—or the planning of it.33

Open and honest communication has been emphasized as crucial in pediatric palliative care.34–36 It has been found that providing psychological support to parents from the healthcare team, even in the last month of their child’s life, facilitates their grieving process. Informing families about the evolving nature of a child’s illness and prognosis is always challenging. Communication about the child’s prognosis has proved valuable for the bereavement outcome.23 Although most parents want to be fully informed of their child’s status, many clinicians continue to avoid this type of communication. Parents who have been informed that their child’s death is imminent are, not surprisingly, more likely to be aware of the pending death.37 Their awareness impacts the opportunity for them to tailor the child’s care according to their wishes. Bringing the child home, as well as planning for a death at home, is more likely to be considered if parents are cognizant of the imminence of death.38 Furthermore, these parents are more likely to talk about death with their child, even more so when they perceive the child also to be aware, which is an approach that has been shown to reduce the risk of psychological morbidity in bereavement.39 However, many children in pediatric palliative care are unable to engage in any type of communication because of age, developmental delay or the nature of the illness. Mothers of children who had severe malignancy and were unable to communicate in their last week of life were more likely to think that death would be best for the child; this finding was not consistent for the fathers.40

Assisting bereaved families is an integral part of pediatric palliative care, beginning with the issues around anticipatory grief at the child’s diagnosis. However, research on bereavement intervention is still in its early stages, and the efficacy of counseling has not yet been well validated.41 Several studies have shown that both professional and social support is beneficial for parents’ grief outcomes, although not all parents find it helpful. Some parents choose to cope on their own, with or without support from family or friends. Over the long term, the social network has proved to be particularly valuable for many bereaved parents. Fathers talk mainly with their spouse, while mothers confide in family, friends, and other bereaved parents. Both types of sharing have a beneficial impact on the grief outcome.23 The identification of parents at risk for pathological grief reactions, and designing optimal intervention for them, remains a critical topic for future research. Emerging from the research are the following recommendations in caring for bereaved parents:

Although long-term consequences often refer to sequelae one or two years following a loss, a time frame for parental bereavement has not been established in the literature.42 Hospitalization for psychological morbidity and an elevated incidence of death have been reported as long-term consequences following the death of a child.28,43 In a Danish study, it was found that both natural and unnatural deaths are more likely among bereaved parents than in a matched sample who were not bereaved. Bereaved mothers had an increased risk throughout the study period of 3 to 18 years, while for fathers the risk was limited to the first 3 years. Unresolved grief emerges as a specific risk factor for the psychological and physical health of both mothers and fathers in the long term. Bereaved fathers with unresolved grief are seven times more likely to report sleep disturbances,44 with the ensuing impact on their capacity for work and overall well-being. A common, and damaging misconception, is that the incidence of separation or divorce is elevated in couples whose child has died. Yet a recent study on long term marital status shows the opposite: bereaved parents actually are less likely to divorce or separate than non-bereaved.45

Siblings

Research on bereaved siblings is extremely limited; their long-term adjustment has yet to be explored in a systematic fashion. However, certain issues have emerged in both clinical observations and empirical studies.46–51 Siblings are often referred to as being invisible because of the parents’ intense involvement in the care of their ill child.52,53 During the illness, the siblings desire open and honest communication within the family, adequate information from clinicians, involvement in the care of the sick child, and support to continue their own interests and activities.52–54 Parents often try to protect the siblings from involvement in the child’s illness, particularly end-of-life care, thinking that it will shelter them from trauma. Yet this well-intentioned approach instead leads the siblings to feel abandoned and excluded from the family tragedy,55 with these feelings persisting long into bereavement. Findings suggest that after the death, siblings perceive their life to change, not only within the family but also in relationships with others outside the family. Clinicians can play an important role in communicating directly with siblings whenever possible and educating the parents about the importance of addressing their needs.

Anticipatory Grief

Anticipatory grief is the process that links everyone who is facing the loss of the child. It is catapulted into being at the time of diagnosis, and wends its way through the illness trajectory until the moment of death. Anticipatory grief initially resembles the grief that immediately follows a death: emotions are alternately raw and numb, and very much in evidence.56 The classic definition of anticipatory grief is “grief expressed in advance when the loss is perceived as inevitable.”57 A broader definition includes loss that is threatened, with the implication of a much longer time frame. Experientially the process reflects the emotional response to the pain of separation before the actuality of loss. The child grieves multiple losses: of his or her healthy self, of function and role, of separation from loved ones. (For discussion of anticipatory grief in the child, see Chapter 3.) The family members face anticipatory grief, and then bereavement after the child dies. They move from the realization that “Our child is going to die” to an even more anguished dawning that “We are going to lose our child.”56 It is at this juncture that the recognition of an inevitable separation has begun. The ebb and flow of anticipatory grief charts an individual course for each family, dependent on the nature and length of the illness trajectory, as well as psychological and cultural factors.

Katy, a 7-year-old girl, had a recurrent dream: “I want to be with my mother, and I can never quite get to her.” The girl recounted the dream in a joint psychotherapy session with her mother. Whereas the mother found the dream “excruciating,” her daughter articulated that “even though the dream is very sad, it’s not a nightmare.” The dream eventually provided the focal image for mother and child to work through the anticipatory grief process.56,p. 70

These phenomena are neither inevitable, nor, when they occur, irreversible. However, they do signify a family’s difficulty in negotiating a phase of the anticipatory grief process. It is crucial that the family not feel chastised for their distancing maneuvers. Rather, this is often a time for a referral to a mental health clinician for individual, marital, or family therapy.56

Three healthy siblings complained to the psychologist: “Every holiday our parents say: ‘Let’s make this holiday perfect for your brother, since it may be his last.’ Meanwhile, he has lived for four years. How long are we supposed to keep this up?”56,p. 73

Enormous grief and anticipatory grief are engendered by the death of another patient. The reverberations are particularly intense when the children have the same disease. On one level, the child and family grieve the loss of their acquaintance or friend. On a deeper level, they are struck with the awareness: “This could have been me/our child … and will I/our child be next?”56 This close sense of identification provides an opening for the child and family to address their own sadness and fear. It is a time for the clinician to be actively present and reassuring until the acute anxiety and grief abate.

With the approach of the child’s death, the family confronts the full intensity of anticipatory grief. The child faces the ultimate leave-taking from everyone and everything; the family stands at the brink of their new life ahead, facing the specter of life without the child. This sequence of anticipatory grief and then bereavement is represented metaphorically (in Fig. 5-4): desperate, powerless and ultimately unsuccessful pleas to prevent the death of a loved one followed by ensuing sadness and attempts at solace.

Bereavement

Death ends a life, but it does not end a relationship…

Parenting is a permanent change in the individual. A person never gets over being a parent. Parental bereavement is also a permanent condition. The bereaved parent, after a time, will cease showing the… symptoms of grief, but the parent does not “get over” the death of a child.59, p. 178

Bereavement follow-up by the professional team is an intrinsic component of comprehensive pediatric palliative care. Without such continuity, many families express anguish over the experience as a double loss. Primary is the death of their child, of an individual, and of a member of the family and the greater community. Compounding this grief, they mourn the loss of their professional family – the treatment team whom they have known and trusted, often over months and years.5–7,9,60Contact from a team member after the child’s death not only assuages the family’s sense of abandonment, but it can also serve a crucial preventive role by identifying families at risk for serious physical, psychological, and social sequelae.

Assessment

A bereavement assessment61 is often done over several sessions, beginning in some instances in the immediate aftermath of the child’s death, and then followed up over weeks or months. The clinician must carefully monitor the pace of the assessment, both within meetings and in scheduling subsequent times, always based on the family’s cues. “Plowing through” an interview for the sake of completing the assessment frequently results in distress and the loss of important information (Box 5-2).

BOX 5-2 Fundamentals of Bereavement Assessment*

In the immediate aftermath of the child’s death, it is important to assess each family member’s response and determine what is needed to carry the family through the crisis, including referrals for medical or mental health issues. Initial discussions often include their wishes for a funeral and/or memorial service and burial and, in some instances, the clarification of logistical issues around transporting the body. If the family has not made advance arrangements, they often need assistance in sorting through their options. This initial assessment also may include sensitive inquiry into the family’s financial resources and identification of people who can help them in the days and weeks ahead. Questions about the course of the child’s illness and death, or unresolved issues with the medical team, can usually wait until after the service has taken place. Other major areas of bereavement assessment include developmental level of the individual and the family; family composition, relationships, and background; significant medical issues; psychological history, particularly coping with past losses or trauma; ethnicity, culture, and spiritual beliefs; available support within the family and community; and access to professional services. A “loss history” encompasses loss in its broadest sense;56 for example, through illness and death, trauma, change in relationships (e.g., divorce); loss of employment and/or financial security; geographical moves. A critical dimension of the loss history includes the experience of immigrant or refugee families: in addition to the loss of their home country, many have suffered unspeakable trauma in their journey to their new home. Given the extreme sensitivity of these issues, which may include fear of legal repercussions if disclosed, utmost care must be exercised in any inquiry.

Through sensitive and thorough inquiry, important information can be gleaned to frame the family’s psychological responses within the context of their own cultural background. The clinician’s effort to understand these factors promotes respect and candor within the therapeutic relationship (Box 5-3).

BOX 5-3 Bereavement Assessment: Topics to Address

Background

The Child’s Illness and Death

Intervention

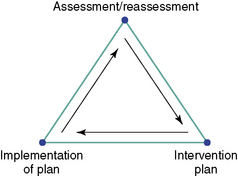

Universally accepted standards for bereavement follow-up do not yet exist in pediatric palliative care. In their absence, the role of individual and family assessment is paramount in providing optimal clinical care, as well as in developing effective protocols that can be empirically tested. The ongoing assessment and/or reassessment process guides the clinician as to what type of intervention would be most valuable at a given time (Fig. 5-5). To achieve the best “fit,” a referral must be based on astute clinical judgment in combination with the unique needs and wishes of the individual or family. It is not uncommon for these needs to fluctuate over time, and thus a variety of support and treatment modalities may be accessed concurrently or sequentially in the bereavement process. Many families turn to their community for support. For example, a deeply religious family may find solace through their spiritual organization. Others turn to self-help bereavement groups at local agencies that rely on volunteers and trained peer counselors. Some people choose more intensive intervention in the form of individual, marital, or family psychotherapy to examine the enduring impact of the child’s illness and death on their lives.

Working with families through death and bereavement can be treacherous ground for inexperienced or unsupported clinicians from any discipline. Throughout the process, it is critical that clinicians keep constant check on their own reactions and expressed beliefs and withhold judgment about the way a family grieves. Consultation with a colleague from a mental health discipline can be valuable in maintaining perspective when working with families in crisis. Furthermore, while many families feel honored and moved at witnessing professionals’ grief for their child, this compassion must be demonstrated without taking over and superseding the family’s own intensity. Clinicians can judge the appropriateness of their involvement in response to the question: “Whose needs are being served?” The answer is unequivocally, “The family’s.”56 This balanced perspective is an absolute of effective bereavement intervention.

Spiritual dimensions

The experience of a child’s illness and death challenges one’s understanding of God’s presence and power. It is difficult to one’s understand the meaning of a young person’s suffering. As part of the “meaning-making” process, it forces many to reconsider what they believe or to believe in something greater than themselves. As the Rev. Carl Howie wrote, “Faith, though subjective, engenders hope and provides meaning for life.”63 To foster such belief requires active listening as individuals describe and define their faith or values, and explore the ways in which their faith can support possibilities and hopes. The process of spiritual assessment and reassessment is ongoing for many children and their families throughout the illness, and afterward.

As spiritual care is provided, the task is to offer emotional and spiritual support to persons of many faiths, cultures, and practices without absolutes but within perimeters.64 For example, some people find more comfort within their own tradition, while others may seek or accept prayer, or supportive listening from persons outside of their own tradition. An important aspect of spiritual assessment is exploring with children and the family which spiritual needs can be met by a newcomer, and which are better met by a known spiritual caregiver. A mitigating factor is often geographical distance, in that the primary spiritual and religious supports may be unavailable for many families. Having to make new spiritual connections is another of the adjustments and losses that accompany the new normal of having an ill child.

The grief of the children who are ill has its own immediacy.65–67 Being in the hospital for an extended period separates them from the family and friends they love—at home, school and in other activities, the neighborhood and their faith community. The children often address their longing for these interrupted, if not suspended, relationships. Awareness of the siblings’ needs is also paramount.

Siblings’ Experiences

Bereaved children face inordinate psychological challenges that test their resilience to the utmost.68 At home, there are two central issues during the acute bereavement period. First is the question of the siblings’ attendance at the funeral. If the parents discuss the issue with the siblings, they can usually make a decision based upon the child’s direct and indirect cues. Ideally, an adult who is close to the child (other than a parent) can keep a close eye on the child during the service, and take the child out or leave early if necessary. No child should ever be forced to attend. Secondly, while it is important to talk about the deceased child, the here-and-now life focus of the well siblings must not be forgotten in the intensity of immediate grief. This is a critical period to ensure the prevention of insidious comparisons with the idealized deceased child, or the beginning of a replacement child process.46

With the death of the patient, the siblings suffer multiple losses: their brother or sister, and then all the roles that were inherent in the relationship.46–51 Siblings must negotiate this permanent loss while feeling the temporary, although often prolonged, psychological loss or distance of their parents who are immersed in their own grief. Siblings struggle with issues, including overwhelming sadness, that are strikingly similar to those faced by bereaved adults.68 Children often report previous losses; thus a “loss history” is crucial in understanding their strengths and vulnerabilities. Young children’s past experience with death, if any, is typically the loss of a grandparent or a pet. They may also talk about objects that they have lost, especially if they are associated with their brother or sister. Children report traumatic memories and fears for the future. Frightening images tend to focus on the illness itself, such as how the person looked, visible symptoms, medical technology, or on the funeral or burial. Worries include: the threat of other losses; loss of a specific aspect of the sibling relationship; religious concerns; harm befalling the child himself or herself; contagion and familial risk of illness; sleep and somatic disorders; and school difficulties. Adolescents often mention sadness about the future (e.g., my brother or sister will never know my children). Anger at the injustice of the loss, as well as at the pain that they must now suffer, takes on many shapes: verbal outbursts; physical aggression and other forms of acting out; and somewhat paradoxically, in withdrawal from others, especially the family.

Staff: cycles of attachment and loss

Clinicians who work with these children and families experience repeated cycles of attachment and loss. They must cope with the cumulative impact of loss over time and find a way to balance their suffering and grief with their ongoing commitment to the work.70–74 (See Chapter 18.) A pediatric hospice nurse described her experience as artwork (Fig. 5-6).

Clinical Vignettes

Michael’S family

Andrea’S family

Frank, 4, sibling of katy, 846

Bobby, 10, and joanne, 17, siblings of cindy, 1446

After the death of Cindy at age 14 of osteosarcoma, her two siblings were followed in psychotherapy for several months. During Cindy’s illness, Bobby had expressed much fear of his leg being amputated (see Figs. 3-7 and 3-8). His identification with her physical illness and suffering continued into bereavement. When asked how he was feeling, Bobby responded, “I feel like a bug is just eating me up.” He then drew a picture of a bald boy with bugs “in the leg and chest only”—the sites of his sister’s cancer (Fig. 5-7). Even more significant was the fact that his asthma, previously mild, became quite severe during this period.

Fig. 5-7 How Bobby feels after Cindy’s death.

(Reprinted with permission from Kellerman, J. Psychological Aspects of Childhood Cancer. (1980). Courtesy of Charles C. Thomas, Publisher, Ltd. Springfield, Illinois.)

In Joanne’s sessions with the psychologist, she reviewed the process of Cindy’s illness and death(see Chapter 3, p. 22) and reminisced about their relationship. She initially expressed a great deal of guilt about not being able to protect her younger sister, as well as regret for some of her past actions and thoughts. “I feel so selfish. I always used to tell Cindy that I wanted my own room. And now I have it—two twin beds—and I am so lonely.” Over the next few months, Joanne did a school project on the cancer center, with the following prologue: “This project is dedicated to my beloved little sister Cindy. At the age of fourteen, my little sister and closest friend departed… Because of my very personal involvement, I chose the cancer institute as my assignment for Urban Studies.”

Summary

These clinical vignettes attest to parents’ and siblings’ wide range of responses, in both content and intensity, to a child’s death. Bereavement is a process of converting presence into absence, actuality into memory. Families must construct a framework for memories of the child that can endure over a lifetime.68 Most individuals, adults and children alike, demonstrate remarkable resilience in their emergence from the child’s death. They derive strength from the deep commitment of the clinicians who care for them.

1 Kuttner L. Making every moment count: pediatric palliative care. National Film Board of Canada, 2003. documentary film

2 Sourkes B., Frankel L., Brown M., Contro N., et al. Food, toys and love: pediatric palliative care. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2005;35(9):345-392.

3 Shaffer MA., Barrows A., editors. The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society. New York: Random House, 2008.

4 Webster’s College Dictionary. Random House. New York, 2000.

5 Contro N., Larson J., Scofield S., et al. Family perspectives on the quality of pediatric palliative care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:14-19.

6 Field MJ., Behrman R.E., editors. When children die: improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2003.

7 Contro N., Larson J., Scofield S., et al. Hospital staff and family perspectives regarding the quality of pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1248-1252.

8 Kreicbergs U., Valdimarsdottir U., Onelov E., et al. Care-related distress: a nationwide study of parents who lost their child to cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9162-9171.

9 D’Agostino N.M., Berlin-Romalis D., Jovcevska V., et al. Bereaved perspectives on their needs. Palliat Support Care. 2008;6:33-41.

10 Hynson J.L., Aroni R., Bauld C., et al. Research with bereaved parents: a question of how not why. Palliat Med. 2006;20:805-811.

11 Scott D.A., Valery P.C., Boyle F.M., et al. Does research into sensitive areas do harm? Experiences of research participation after a child’s diagnosis with Ewing’s sarcoma. Med J Aust. 2002;177:507-510.

12 Kreicbergs U., Valdimarsdottir U., Steineck G., et al. A population-based nationwide study of parents’ perceptions of a questionnaire on their child’s death due to cancer. Lancet. 2004;364:787-789.

13 Dyregrov K. Bereaved parents’ experience of research participation. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:391-400.

14 Sourkes B. Armfuls of Time: The psychological experience of the child with a life-threatening illness. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1995.

15 Raphael B. The anatomy of bereavement. New York: Basic Books, 1983.

16 Rando T. Parental loss of a child. Champaign Ill: Research Press Company, 1986.

17 Rosen E., editor. Families facing death. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1990.

18 Rosof B.D., editor. The worst loss. New York: Henry Holt, 1994.

19 Crawley L.M. Racial, cultural, and ethnic factors influencing end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(1):S58-S67.

20 Doka K., Tucci A., editors. Living with grief: children and adolescents. Washington, DC: Hospice Foundation of America, 2008.

21 Wheeler I. Parental bereavement: the crisis of meaning. Death Stud. 2001;25:51-66.

22 Whittam E.H. Terminal care of the dying child: psychosocial implications of care. Cancer. 1993;71:3450-3462.

23 Kreicbergs U.C., Lannen P., Onelov E., et al. Parental grief after losing a child to cancer: impact of professional and social support on long-term outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3307-3312.

24 Jalmsell L., Kreicbergs U., Onelov E., et al. Symptoms affecting children with malignancies during the last month of life: a nationwide follow-up. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1314-1320.

25 Wolfe J., Grier H.E., Klar N., et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:326-333.

26 Hendricks-Ferguson V. Physical symptoms of children receiving pediatric hospice care at home during the last week of life. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35:E108-E115.

27 Kreicbergs U., Valdimarsdottir U., Onelov E., et al. Anxiety and depression in parents 4–9 years after the loss of a child owing to a malignancy: a population-based follow-up. Psychol Med. 2004;34:1431-1441.

28 Li J., Precht D.H., Mortensen P.B., et al. Mortality in parents after death of a child in Denmark: a nationwide follow-up study. Lancet. 2003;361:363-367.

29 Li J., Laursen T.M., Precht D.H., et al. Hospitalization for mental illness among parents after the death of a child. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1190-1196.

30 Sirki K., Saarinen-Pihkala U.M., Hovi L. Coping of parents and siblings with the death of a child with cancer: death after terminal care compared with death during active anticancer therapy. Acta Paediatr. 2000;89:717-721.

31 Shanfield S.B., Benjamin A.H., Swain B.J. Parents’ reactions to the death of an adult child from cancer. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141:1092-1094.

32 Goodenough B., Drew D., Higgins S., et al. Bereavement outcomes for parents who lose a child to cancer: are place of death and sex of parent associated with differences in psychological functioning? Psychooncology. 2004;13:779-791.

33 Dussel V., Kreicbergs U., Hilden J.M., et al. Looking beyond where children die: determinants and effects of planning a child’s location of death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:33-43.

34 Masera G., Spinetta J.J., Jankovic M., et al. Guidelines for assistance to terminally ill children with cancer: a report of the SIOP Working Committee on psychosocial issues in pediatric oncology. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1999;32:44-48.

35 Mack J.W., Hilden J.M., Watterson J., et al. Parent and physician perspectives on quality of care at the end of life in children with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9155-9161.

36 Mack J.W., Wolfe J., Grier H.E., et al. Communication about prognosis between parents and physicians of children with cancer: parent preferences and the impact of prognostic information. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5265-5270.

37 Valdimarsdottir U., Kreicbergs U., Hauksdottir A., et al. Parents’ intellectual and emotional awareness of their child’s impending death to cancer: a population-based long-term follow-up study. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:706-714.

38 Surkan P.J., Dickman P.W., Steineck G., et al. Home care of a child dying of a malignancy and parental awareness of a child’s impending death. Palliat Med. 2006;20:161-169.

39 Kreicbergs U., Valdimarsdottir U., Onelov E., et al. Talking about death with children who have severe malignant disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1175-1186.

40 Hunt H., Valdimarsdottir U., Mucci L., et al. When death appears best for the child with severe malignancy: a nationwide parental follow-up. Palliat Med. 2006;20:567-577.

41 Stroebe W., Schut H., Stroebe M.S. Grief work, disclosure and counseling: do they help the bereaved? Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:395-414.

42 Davies R. New understandings of parental grief: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2004;46:506-513.

43 Li J., Laursen T.M., Precht D.H., et al. Hospitalization for mental illness among parents after the death of a child. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1190-1196.

44 Lannen P.K., Wolfe J., Prigerson H.G., et al. Unresolved grief in a national sample of bereaved parents: impaired mental and physical health 4 to 9 years later. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5870-5876.

45 Ellegard A., Kreicbergs U. Risk of parental dissolution of partnership following the loss of a child to cancer: a population-based long-term follow-up. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(1):100-101.

46 Sourkes B. Siblings of the pediatric cancer patient. In: Kellerman J., editor. Psychological aspects of childhood cancer. Springfield, Ill: Charles C. Thomas; 1980:47-69.

47 Sourkes B. Siblings of the child with a life-threatening illness. J Child Contemp Soc. 1987;19:159-184.

48 Rosen H. Unspoken grief: coping with sibling loss. Lanham, Md: Lexington Books, 1990.

49 Davies B. Shadows in the sun: the experience of sibling bereavement in childhood. Philadelphia: Brunner-Mazel, 1999.

50 Bluebond-Langner M. In the shadow of illness: parents and siblings of the chronically ill child. Princeton, NJ: University Press, 2000.

51 DeVita-Raeburn E. The empty room: surviving the loss of a brother or sister at any age. New York: Scribner Press, 2004.

52 Nolbris M., Hellstrom A.L. Siblings’ needs and issues when a brother or sister dies of cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2005;22:227-233.

53 Wilkins K.L., Woodgate R.L. A review of qualitative research on the childhood cancer experience from the perspective of siblings: a need to give them a voice. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2005;22:305-319.

54 Alderfer M.A., Labay L.E., Kazak A.E. Brief report: does posttraumatic stress apply to siblings of childhood cancer survivors? J Pediatr Psychol. 2003;28:281-286.

55 Ballard K.L. Meeting the needs of siblings of children with cancer. Pediatr Nurs. 2004;30:394-401.

56 Sourkes B. The deepening shade: psychological aspects of life-threatening illness. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1982.

57 Aldrich C.K. Some dynamics of anticipatory grief. In: Schoenberg B., Carr A., Kutscher A., et al, editors. Anticipatory grief. New York: Columbia University Press, 1974.

58 Anderson R. Notes of a survivor. In: Troup S.B., Greene W.A., editors. The patient, death and the family. New York: Scribner, 1974.

59 Klass D. Parental grief: solace and resolution. New York: Springer, 1988.

60 deCinque N., Monterosso L., Dadd G., et al. Bereavement support for families following the death of a child from cancer: practice characteristics of Australian and New Zealand pediatric oncology units. Journal of Pediatrics and Child Health. 2004;40(2):1-5.

61 Contro N., Scofield S. The power of their voices: child and family assessment in pediatric palliative care. In: Goldman A., Haines R., Liben S., editors. Oxford textbook of pediatric palliative care. London: Oxford University Press; 2006:143-153.

62 Sourkes B. Psychotherapy with the dying child. In: Chochinov H., Breitbart W., editors. Psychiatric dimensions of palliative care. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000:265-272.

63 Science, art and theology: a call for dialogue by Dr. Carl G. Howie, Richmond, Va, Union Theological Seminary.

64 Mitchell K., Anderson H. All our losses, all our griefs: resources for pastoral care. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1983.

65 Huntley T. Helping children grieve when someone they love dies. Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1991.

66 Komp D. Children are… images of grace: a pediatrician’s trilogy of faith, hope and love. Grand Rapids Mich: Zonderman Publishing, 1996.

67 Grossoehme D. The pastoral care of children. Oxford: Haworthe Press, 1999.

68 Hanus M., Sourkes B. Les enfants en deuil: portraits du chagrin [Bereaved children: portraits of grief]. Paris: Frison-Roche, 1997.

69 Saint-Exupery A. de. The little prince. Harcourt, Brace and World, 1971.

70 Rashotte J., Fothergill-Boourbonnais F., Chamberlain M. Pediatric intensive care nurses and their grief experiences: a phenomenological study. Heart Lung. 1997;26(5):372-386.

71 Rushton C. The other side of caring: caregiver suffering. In: Carter B., Levetown M., editors. Palliative care for infants, children and adolescents: a practical handbook. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press; 2004:220-243.

72 Serwint J., Rutherford L., Hutton N. Personal and professional experiences of pediatric residents concerning death. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(1):70-79.

73 Swinney R., Yin L., Lee A., et al. The role of support staff in pediatric palliative care: their perceptions, training and available resources. J Palliat Care. 2007;23(1):44-50.

74 Papadatou D., editor. In the face of death: professionals who care for the dying and the bereaved. New York: Springer, 2009.