CHAPTER 27 Anti-Reflux Procedures

Step 1: Surgical Anatomy

Step 2: Preoperative Considerations

♦ Gastroesophageal reflux in the child is largely a clinical diagnosis based on one or more conditions (e.g., emesis, chronic cough, wheezing, aspiration pneumonia) and their sequelae (e.g., esophagitis, nutritional failure or growth retardation, apnea, sudden infant death syndrome, or acute life-threatening events).

♦ The clinical diagnosis is supported by pH probe studies. A cookie-swallow study can be helpful to assess penetration. On esophagram, most infants appear to have reflux, limiting the utility of this test. We routinely perform an upper gastrointestinal (GI) series to rule out malrotation before operation, but this can also be ascertained laparoscopically by determining the location of the ligament of Treitz, cecum, and small bowel when the upper GI is equivocal. Some advocate a gastric emptying study. An esophagogastroscopy with biopsy is not imperative but can be helpful for identification of reflux stigmata. The liberal use of Nissen fundoplication in neurologically impaired children appears to be advantageous. Antibiotic prophylaxis is achieved by administering a first-generation cephalosporin (e.g., cefazolin) 30 minutes before surgical incision and continued for 24 hours postoperatively.

♦ There are no absolute contraindications to an attempt at laparoscopy. However, extensive adhesions from prior surgery (including open Nissen or gastrostomy), ventilator or hemodynamic instability (poor tolerance of CO2 insufflation or pressure), marked visceral dilation (often from excessive preintubation bagging or preceding ileus), hepatosplenomegaly, existing ventriculoperitoneal shunt or baclofen pump, and scoliosis can make a laparoscopic approach more challenging.

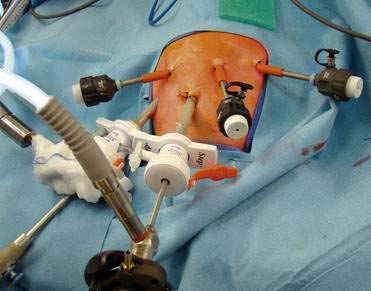

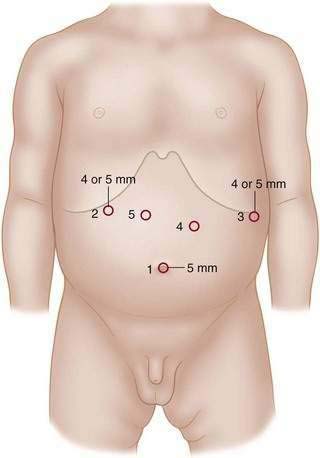

♦ There are important differential considerations for infants who weigh less than 5 kg compared with a larger child or adolescent. Small infants are best served by using 3-mm instruments and liver retractor, whereas 5-mm instruments are more suitable for a larger child. Of additional consideration is the larger child with scoliosis, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, or additional hardware (e.g., baclofen pump), which can make a routine case more technically demanding with respect to port placement and overall operative strategy (Fig. 27-2).

♦ An inventory of equipment follows (some shown in Fig. 27-3): trocars (5 mm for right upper quadrant liver port and umbilical camera), “radially” expanding sheaths and trocars, scopes (4 mm, 30 degrees;, 5 mm, 30 degrees; and 10 mm, 30 degrees), graspers (Maryland or Duckbill), needle drivers, hook cautery (alternative Harmonic scalpel), fundus grasper, liver retractor and holder), suture, suction irrigator, video monitors, and laparoscopic tower.

Step 3: Operative Steps

Anesthetic Induction

Positioning

♦ Patients are placed supine at the end of the bed with proper pressure-point support. Larger patients (i.e., weighing more than 10 kg) may be placed in stirrups or leg-sleds, whereas for infants who weigh less than 10 kg, feet are simply placed in frog-leg position, wrapped in ABD pads (Fig. 27-4).

Incision and Port Placement

Procedure

♦ Liver retractor placement to hold up left lobe of liver, exposing the esophageal hiatus (Fig. 27-7)

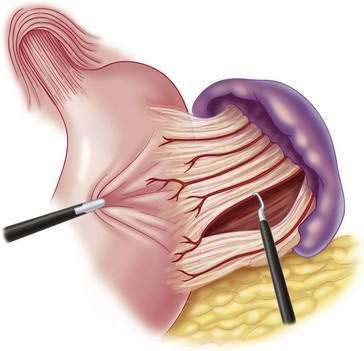

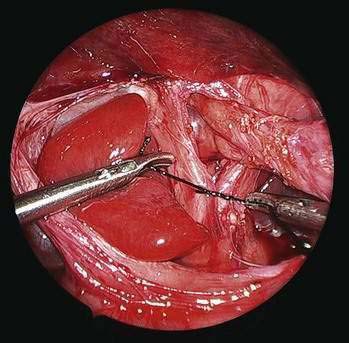

♦ Using hook cautery or Harmonic scalpel, take down the gastrosplenic ligament and short gastric vessels up to the left diaphragmatic crus (Fig. 27-8). Continue to take down the gastrohepatic ligament up to right diaphragmatic crus (Fig. 27-9).

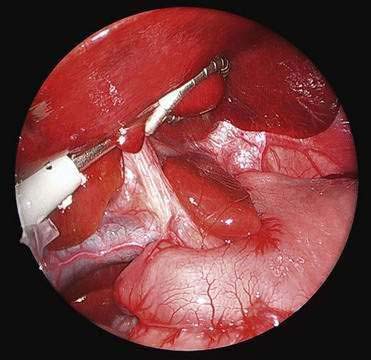

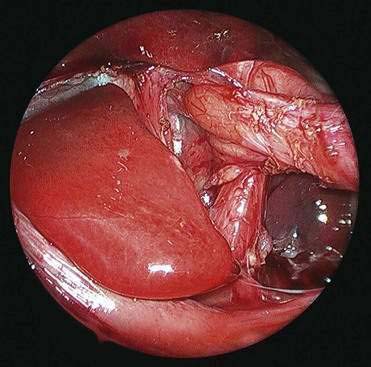

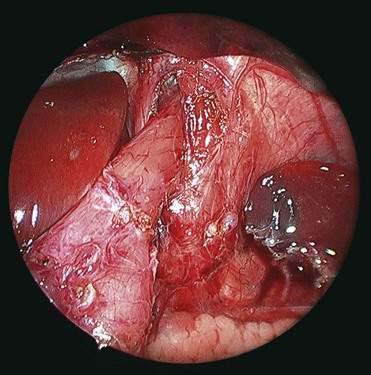

♦ Open the retroesophageal space inferior to the crura and superior to left gastric veins. Fig. 27-10 reveals hiatal hernia as viewed from right side. Fig. 27-11 reveals the view from the left side of an adequately mobilized esophagus and gastroesophageal junction well within abdominal cavity.

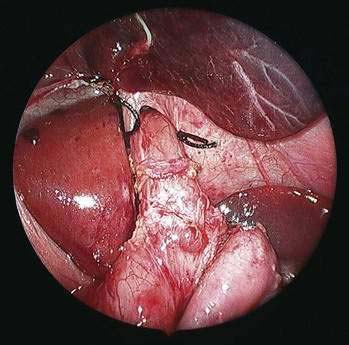

♦ Perform cruroplasty (close defect made) with one to three stitches (2-0 or 3-0 silk on ski needle) (Fig. 27-12).

♦ Place “collar” stitches between the esophagus and crura at 3 and 9 o’clock positions to help keep the esophagus in an intra-abdominal location (this is especially helpful when a large hiatal hernia is present) (Fig. 27-13).

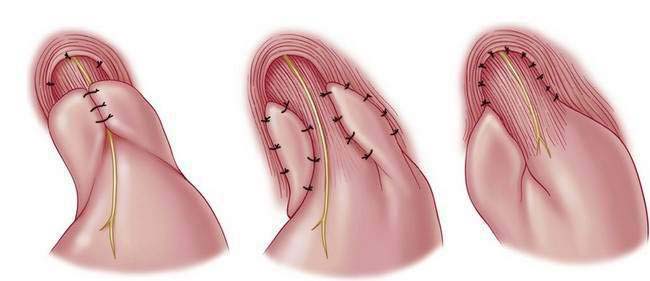

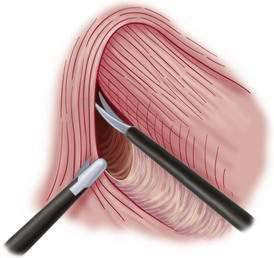

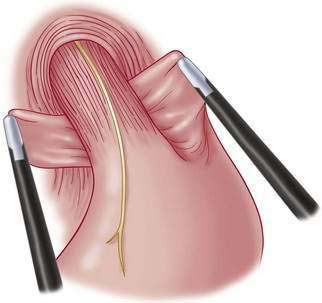

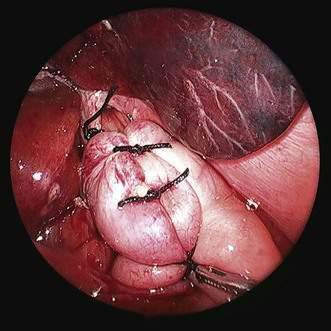

♦ Wrap fundus 360 degrees beginning with “shoe-shine” maneuver (Fig. 27-14) and culminating in three stitches (incorporating fundus-esophagus-fundus) for wrap (distance approximately 2 to 3 cm) (Figs. 27-15 and 27-16).

Step 4: Postoperative Management

♦ Patient is kept NPO (nothing by mouth) overnight. On postoperative day 1 clear liquids are started after a trial of venting G-tube (if present). Retention sutures around the G-tube are removed on postoperative day 2. Advancement to and maintenance of a “no-chunk” diet for 3 weeks minimum typically follows, although a broad variety of feeding regimens and strategies might be used.

Step 5: Pearls and Pitfalls

♦ Infants too large for a 3-mm liver retractor and too small for 5-mm liver retractor may require repositioning of the retractor when the gastrohepatic ligament is being divided. Ideally, one should set the liver retractor only once during the course of the operation.

♦ The camera may need to be moved during the course of the operation to assist with visualization between the umbilicus and the left midabdomen (no. 4) port site (especially if working around a preexisting G-tube).

♦ Judicious and patient dissection (including adhesiolysis where appropriate) is one of the keys of successful laparoscopy. Use of additional ports is encouraged and may help with exposure or dissection when difficulties are encountered or initial positioning is not optimal. Once progress is no longer being made, an alternative plan (e.g., conversion to open) may be entertained.

♦ Ongoing, cooperative discussion between the surgeon and the anesthesiologist is critical. Minimal preintubation bagging avoids preventable and unpleasant visceral distention. Additionally, the infant must be kept appropriately anesthetized to avoid the sense of “fighting the patient.” In smaller infants with large hiatal hernias, entrainment of CO2 into the mediastinum during the dissection may cause respiratory compromise and require temporary discontinuation of insufflation to allow recovery from respiratory embarrassment.

Frykman PK, Georgeson KE. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. In: Bax KNMA, Georgeson KE, Rothenberg SS, Valla J-S, Yeung CK, editors. Endoscopic surgery in infants and children. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2008:253-259.

Georgeson KE. Laparoscopic fundoplication and gastrostomy. Pediatr Ann. 1993;22(11):675-677.

Rothenberg SS. Laparoscopic Nissen procedure in children. Semin Laparosc Surg. 2002;9(3):146-152.