CHAPTER 25 Anterior sciatic block

Surface anatomy

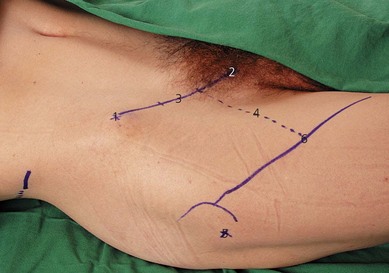

Important bony structures for the anterior landmark-based sciatic block include the anterior superior iliac spine, the pubic tubercle, and the greater trochanter of the femur (Fig. 25.1). A line is drawn between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle (along the inguinal ligament). This line is divided into equal thirds. At the junction between the medial one-third and the lateral two-thirds, a perpendicular line is drawn extending into the thigh. A further line is drawn from the greater trochanter, parallel to the inguinal ligament. Where the perpendicular line crosses this line is the needle insertion point. Rotation of the hip due to leg position or pathology can change anatomic relations; this must be remembered when the needle insertion point is chosen. Important anatomic details include the close proximity of the femoral nerve at the site of needle insertion.

Sonoanatomy

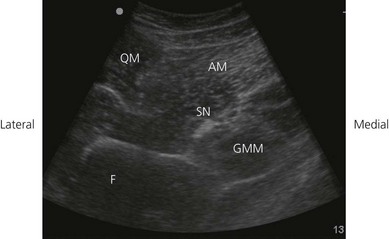

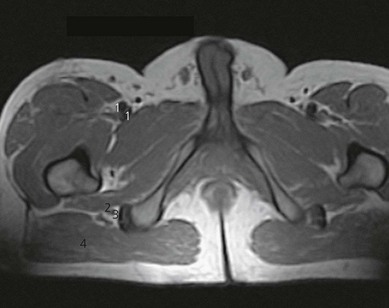

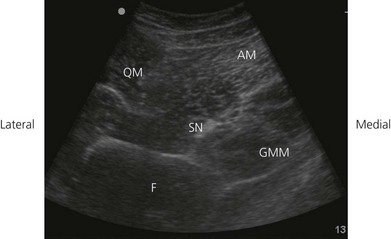

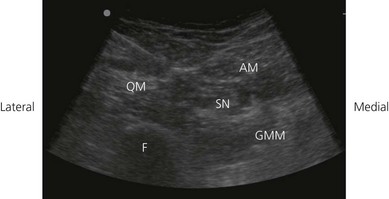

The sciatic nerve may be difficult to visualize in this region because of the required depth of beam penetration and the use of a lower frequency transducer. A transverse transducer orientation is used (Fig. 25.2). Visualization of the sciatic nerve may be obstructed by the lesser trochanter of the femur. Perform a systematic anatomical survey from proximal to distal and from lateral to medial. First identify the femur, a curved hyperechoic line with an underlying bone shadow. Move the transducer proximally and distally to identify the lesser trochanter. Identify the anterior muscular layers: quadriceps muscles laterally and the adductor muscles medially (approximately 8 cm from inguinal crease in adults; Fig. 25.2). Identify the gluteus maximus muscle posteriorly. The gluteus maximus muscle bulk gets smaller as the transducer is moved more distally away from the inguinal crease. Locate the hyperechoic sciatic nerve deep to the adductor muscles and posterior to the femur (Fig. 25.3). The ultrasound image of the sciatic nerve in cross section is typically seen as an oval-to-circular hyperechoic structure. It is often vaguely delineated or appears isoechoic to the surrounding muscles, the latter particularly if using a tangential ultrasound beam plane.

Figure 25.2 Transverse transducer orientation for the ultrasound-guided anterior sciatic nerve block.

If the lesser trochanter obstructs visualization of the sciatic nerve, move the transducer further on the medial aspect of the anterior thigh and orient the transducer in a slightly anterior–posterior direction. This orientation will allow the transducer to capture the best possible transverse view of the sciatic nerve behind (posterior to) the lesser trochanter. Angle the transducer slightly cephalad or caudad to optimize the angle of incidence (90°) to capture the best possible nerve image. Scan the nerve proximally (cephalad) and distally (caudad) to follow the course of the nerve and to confirm nerve identity. A longitudinal scanning approach can also be used to identify the sciatic nerve at the lesser trochanter (Fig. 25.4).

Technique

Landmark-based approach

The patient is placed in the supine position with the leg in the neutral position. The operator stands on the side to be blocked, at the level of the patient’s thigh. The area of the needle track is anesthetized with local anesthetic. Analgesia or sedation is very desirable for this block. A 150-mm insulated needle is inserted perpendicularly with some lateral angulation in line with the lesser trochanter of the femur (Fig. 25.5). The stimulating current is set at 1.2 mA, 2 Hz, and 0.1 ms.

On contact with the lesser trochanter, the needle is withdrawn, angulated in a less lateral orientation, and advanced; the sciatic nerve is usually stimulated 3–4 cm deeper (Fig. 25.6). Total needle depth to the sciatic nerve is approximately 70% of thigh thickness; usually 8–12 cm. The needle is advanced slowly until the appropriate muscle response is obtained: tibial nerve component produces plantar flexion and inversion of the foot, while common peroneal stimulation produces dorsiflexion and eversion of the foot. The needle position is adjusted while reducing the current to 0.35 mA with maintenance of the muscle response. Hamstring contraction response is not accepted. On its path to the sciatic nerve, femoral nerve stimulation may be initially found. To ensure safe practice, the femoral nerve should not be blocked before sciatic nerve block.

Incremental injection of 20–30 mL of local anesthetic is made with repeated aspiration.

Ultrasound-guided approach

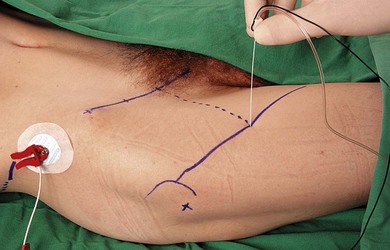

Intravenous access, electrocardiogram (ECG), pulse oximetry and blood pressure monitoring are established. Maximized comfort for the operator and patient is an important step in pre-procedure preparation. For the ultrasound-guided anterior sciatic block, the patient is placed in the supine position with the knee flexed and the ipsilateral hip externally rotated. The operator stands on the side to be blocked with the ultrasound screen on the same side above the hip (Fig. 25.7).

A skin wheal of local anesthetic is raised at a distance from the medial aspect of the ultrasound transducer to facilitate sterility and allow a shallow angle of approach to improve needle visualization. The needle bevel should face the active face of the transducer to improve visibility of the needle tip. A free hand technique rather than the use of a needle guide is preferred. A 22-GA × 120-mm insulated regional block needle (B. Braun, Bethlehem PA) is inserted within the plane of imaging to visualize the entire shaft and bevel along the path of the ultrasonic beam (Fig. 25.8). Advance the needle in a medial to lateral direction as well as an anterior to posterior direction when the thigh is externally rotated.

A hypoechoic (fluid) expansion can be seen during local anesthetic injection (Fig. 25.10). Fluid expansion in the adductor muscles indicates intramuscular injection. Appropriate needle advancement is required. Inject 15–20 mL of local anesthetic for postoperative analgesia.

Adverse effects

Beck GP. Anterior approach to the sciatic nerve. Anesthesiology. 1963;24:222-224.

Chan VW, Nova H, Abbas S, et al. Ultrasound examination and localization of the sciatic nerve: a volunteer study. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(2):309-314.

Chantzi C, Saranteas T, Zogogiannis J, et al. Ultrasound examination of the sciatic nerve at the anterior thigh in obese patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2007;51(1):132.

Elsraete V, Poey C, et al. New landmarks for the anterior approach to the sciatic nerve block: imaging and clinical study. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:214-218.

Ota J, Sakura S, Hara K, Saito Y. Ultrasound-guided anterior approach to sciatic nerve block: a comparison with the posterior approach. Anesth Analg. 2009;108(2):660-665.

Tsui BC, Ozelsel TJ. Ultrasound-guided anterior sciatic nerve block using a longitudinal approach: ‘expanding the view’. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008;33(3):275-276.