Anterior Blepharitis

Treatment Strategies

Introduction

Blepharitis is one of the most common ocular disorders seen by eye care specialists and is found in almost 47% of ophthalmic patients. Approximately 30 million Americans may be affected.1 Blepharitis is common in middle-aged patients, and its incidence increases with age. Blepharitis may be under-reported as the primary reason for an office visit, since the patient may present for a dry eye assessment, surgical evaluation or routine examination.2 Although common, blepharitis is often overlooked, misdiagnosed or inadequately treated. The lack of diagnosis may be due to poor understanding of the condition and the absence of a widely accepted definition and classification scheme, as well as the lack of a clinically straightforward algorithm to aid in the diagnosis and treatment of blepharitis. Recently, diagnostic and treatment algorithms for practitioners have been developed. A simplified clinically relevant terminology based on anatomic location is key to improve diagnosis and management.3

Anterior blepharitis refers to acute or chronic inflammation and its associated signs and symptoms involving the anterior portion of the eyelid (eyelashes and follicles) (Fig. 9.1).1 In one study, anterior blepharitis was found to account for 12% of all eyecare patients seeking treatment for generalized ocular discomfort or irritation.4 Unlike posterior blepharitis, which primarily involves the meibomian glands, anterior blepharitis appears to be more common in younger (mean age of 42) and female (80%) patients. A variety of conditions (including age, allergy, immune system problems, hormonal changes, bacteria, rosacea and dermatitis) may contribute to its development.1,5

Anterior blepharitis typically involves an excessive colonization of normal lid bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Corynebacterium, or others) and inflammation.1,3,6–7 Infection occurs at the origins of the eyelashes and involves the follicles and surrounding tissues.5 Bacteria elaborate virulence factors including toxins, enzymes, and waste products that enter the tear film and contribute to ocular surface inflammation and irritation.5,8 Lipolytic exoenzymes produced by the lid bacteria hydrolyze wax and sterol esters release irritating free fatty acids.3 These breakdown products can contribute to the disruption of tear film integrity.5,8

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Diagnosis of anterior blepharitis is typically based on signs, symptoms, history, and external/lid examination. Typically bilateral, anterior blepharitis is both chronic and intermittent and can significantly impact quality of life.1 In its acute phase, patients often present with bright red, puffy, irritated eyes that itch or burn.3 Additional signs include lid and lash debris, watery eyes, and intermittent effects on vision.

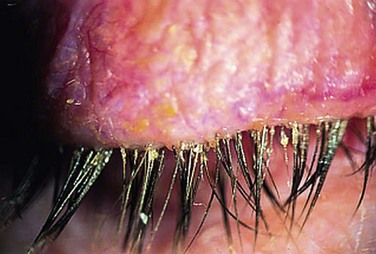

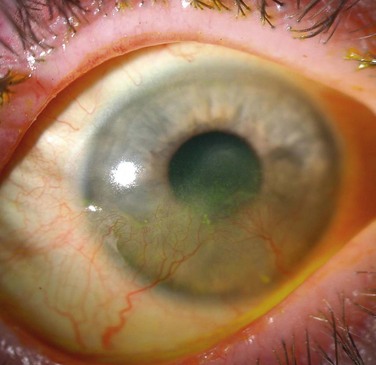

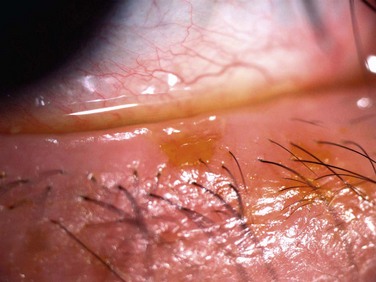

Staphylococcal-related anterior blepharitis affects predominantly young to middle-aged women, and keratoconjunctivitis sicca (dry eye) can present in up to 50% of these patients6,8 Eyelash loss or breakage and misdirection, collarettes or scurf on the eyelids and lashes, and fine eyelid ulcerations along the lash margin can also be seen (Fig. 9.2).8 In severe cases, staphylococcal hypersensitivity syndrome may cause ocular surface inflammation, corneal neovascularization and scarring, and decreased vision (Fig. 9.3).

Seborrhea-related disease generally affects older patients and is indiscriminate of gender.6,9 Aqueous tear deficiency can be seen in 25% to 40% of these patients.8 Seborrheic dermatitis is a skin condition associated with flaking and scaling, involving the eyebrows and eyelids (Fig. 9.4). The cause of this skin condition is not well understood. Seborrhea sometimes appears in patients with weakened immune systems. Fungi or certain types of yeast that feed on lipids in the skin may also contribute to seborrheic dermatitis with accompanying blepharitis.

Figure 9.4 Seborrheic dermatitis.

A thorough history and comprehensive eye examination is critical to confirming a diagnosis. Patient history can help, as the presence of underlying skin conditions such as seborrheic dermatitis or atopic eczema may point to the diagnosis of seborrheic disease.8 Clinicians should look for signs of both infection and inflammation.

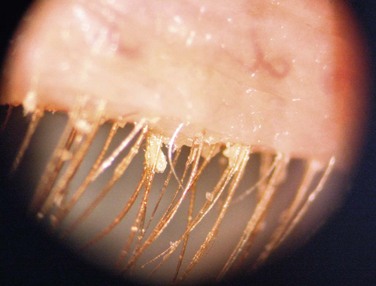

The differential diagnosis can be confounded by similar conditions with other etiologies, and includes infectious, inflammatory, and seborrheic etiologies.10 Infectious etiologies include staphylococcal and other bacteria, herpes simplex virus (Fig. 9.5), Demodex (Figs 9.6 and 9.7) and Phthrisis pubis (Fig. 9.8). Rosacea-related anterior blepharitis is primarily inflammatory but is often associated with bacterial overgrowth as well. Rosacea-related disease, if untreated or inadequately treated, may lead to severe corneal neovascularization and scarring with resultant poor vision (Fig. 9.9). Anterior blepharitis is also found in patients with seborrhea.

Figure 9.5 Herpes simplex-related anterior blepharitis.

Figure 9.6 Demodex blepharitis.

Figure 9.8 Phthirus pubis anterior blepharitis.

Figure 9.9 Rosacea-related anterior blepharitis with severe corneal scarring and neovascularization.

With Demodex blepharitis, microscopic mites (Demodex folliculorum) and their waste materials cause clogging of eyelash follicles and associated inflammation (Figs 9.6 and 9.7). Demodex brevis can also affect the oil glands of the skin and eyelids causing secondary blepharitis. While presence of these tiny mites is common, the development of Demodex blepharitis may be due to unusual allergic or immune system responses.

In addition, patients may experience signs or symptoms involving both the anterior and posterior eyelids, since anterior blepharitis is often found concomitantly with meibomian gland disease.3 Chalazion formation and bacterial conjunctivitis may be seen in these patients, due to posterior lid involvement and bacterial overgrowth. In addition, the proximity of the eyelids to ocular structures can lead to other disorders (such as dry eye) due to inflammatory mediator release and/or tear film instability.11

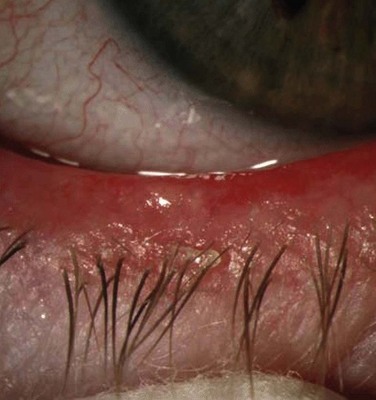

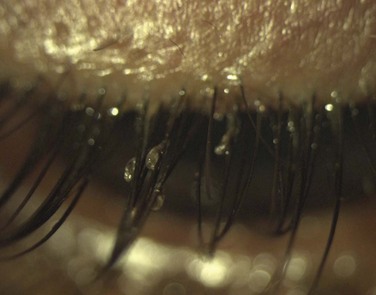

Presentation should be categorized by the presence or absence of key signs and symptoms. Symptoms include stickiness, crusting, burning of the eyelids upon awakening and eyelid irritation, both acute and chronic. Principle signs include erythema, edema and eyelid and lash debris (collarettes and scurf) (Figs 9.10 and 9.11).

Figure 9.10 Anterior blepharitis with scurf.

Figure 9.11 Anterior blepharitis with collarettes.

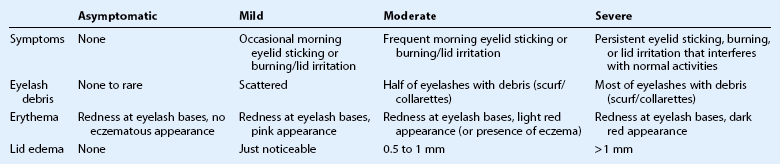

Classification of patients based upon disease severity is a critical element which guides treatment decisions. Anterior blepharitis can be divided into asymptomatic and symptomatic disease. Patients presenting with symptomatic blepharitis may be further subdivided into mild, moderate or severe categories based upon signs and symptoms present and degree of severity (Table 9.1).

Treatment

In patients with anterior blepharitis undergoing ocular surgery (such as cataract or laser in situ keratomileusis), a ‘quiet eye’ without evidence of infection or inflammation is desired, in order to optimize results and prevent the development of postoperative infection.2 Therapy should induce remission by impacting these etiologies in the event of an acute exacerbation, followed by some type of maintenance strategy to prevent recurrence. The use of topical antibiotic therapy preoperatively and betadine skin prep on the day of surgery is crucial to decrease the risk of postoperative infection.

Topical antibiotic therapy is necessary in the management of moderate to severe disease, especially when bacterial overgrowth is observed. Historically, bacitracin and aminoglycosides (gentamicin and tobramycin) comprised the most commonly used topical antibiotics for the treatment of blepharitis. Administration was generally limited to acute anterior blepharitis flares, to minimize the opportunity for development of resistance and minimize associated ocular surface toxicity. Antibiotic ointments can also be utilized to increase the contact time with the eyelid surface and aid in symptomatic relief from ocular surface irritation.11

Recently, macrolide antibiotics (such as erythromycin and azithromycin) have been advocated since they possess both anti-inflammatory and anti-infective properties. Topical azithromycin has exceptional affinity for tissue and a long half-life, making it an attractive treatment option for eyelid disease.12 Erythromycin is also available as an ophthalmic ointment but does not penetrate tissue well.

Topical corticosteroids target the inflammatory component of blepharitis. They are generally reserved for moderate to severe inflammation and complicated presentations.8 The selection of steroid used should take into account the potency needed for adequate therapeutic response while balancing the risk of side effects.

Simultaneous steroid and antibiotic use as induction therapy can be beneficial in patients with moderate to severe disease. This treatment should be used judiciously since long-term corticosteroid use can increase the risk of elevated intraocular pressure, exacerbate the infectious process leading to superinfection, and stimulate cataract development.13 For safety reasons, the lowest effective steroid dose should be used and patients should be monitored closely for safety and efficacy. In patients with moderate or severe disease, the use of fixed-dose combination products may facilitate patient administration and increase convenience. For patients in need of chronic anti-inflammatory therapy to prevent recurrences, low-dose topical steroid (such as fluorometholone or loteprednol) or topical cyclosporine 0.05% may be considered to prevent disease recurrence, while minimizing the risk of long-term side effects.

Treatment of other less common causes of anterior blepharitis targets the underlying etiology. For herpes simplex virus-related blepharitis, topical and/or oral antiviral therapy along with ocular surface lubrication and cool compresses control symptoms and shorten the duration of the active disease. For fungi and yeast overgrowth associated with seborrhea, treatment of the underlying disease and lid hygiene are generally curative. For Demodex-associated anterior blepharitis, eyelid scrubs combined with tea tree oil have been advocated. Sulfur oil and antiparasitic gels (metronidazole) have also been recommended. Topical steroid use may be beneficial in controlling inflammation seen in association with Demodex-related disease.14 In cases of Phthiriasis pubis-related anterior blepharitis, therapy includes careful removal of the lice and nits (louse eggs) and local application of pediculocide. Patient and sexual contacts need treatment of the infection source to prevent disease recurrence.

References

1. Donnenfeld, ED, Mah, FS, McDonald, MD, et al. New considerations in the treatment of anterior and posterior blepharitis. Refr Eyecare. 2008;12:1–15.

2. Lemp, MA, Nichols, KK. Blepharitis in the United States 2009: a survey-based perspective on prevalence and treatment. Ocul Surf. 2009;7(Suppl. 2):S1–S14.

3. Foulks, GN, Lemp, MA. Blepharitis: a review for clinicians. Refr Eyecare. 2009;13:1–10.

4. Venturino, G, Bricola, G, Bagnis, A, et al. Chronic blepharitis: treatment patterns and prevalence. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 44, 2003. [E-Abstract 774].

5. Dougherty, JM, McCulley, JP. Bacterial lipases and chronic blepharitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1986;27:486–491.

6. McCulley, JP, Dougherty, JM, Deneau, DG. Classification of chronic blepharitis. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:1173–1180.

7. Groden, LR, Murphy, B, Rodnite, J, et al. Lid flora in blepharitis. Cornea. 1991;10:50–53.

8. Jackson, WB. Blepharitis: current strategies for diagnosis and management. Can J Ophthalmol. 2008;43:170–179.

9. McCulley, JP, Dougherty, JM. Blepharitis associated with acne rosacea and seborrheic dermatitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1985;25:159–172.

10. Bernardes, TF, Bonfioli, AA. Blepharitis. Semin Ophthalmol. 2010;25:79–83.

11. Abelson, M, Shapiro, A, Tobey, C. Breaking down blepharitis. Rev Ophthalmol. 2011:74–78.

12. Giamarellos-Bourboulis, EJ. Macrolides beyond the conventional antimicrobials: a class of potent immunomodulators. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;31:12–20.

13. David, DS, Berkowitz, JS. Ocular effects of topical and systemic corticosteroids. Lancet. 1969;294:149–151.

14. Kheirkhah, A, Casas, V, Li, W, et al. Corneal manifestations of ocular Demodex infestation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:743–749.