CHAPTER 61 Anterior abdominal wall

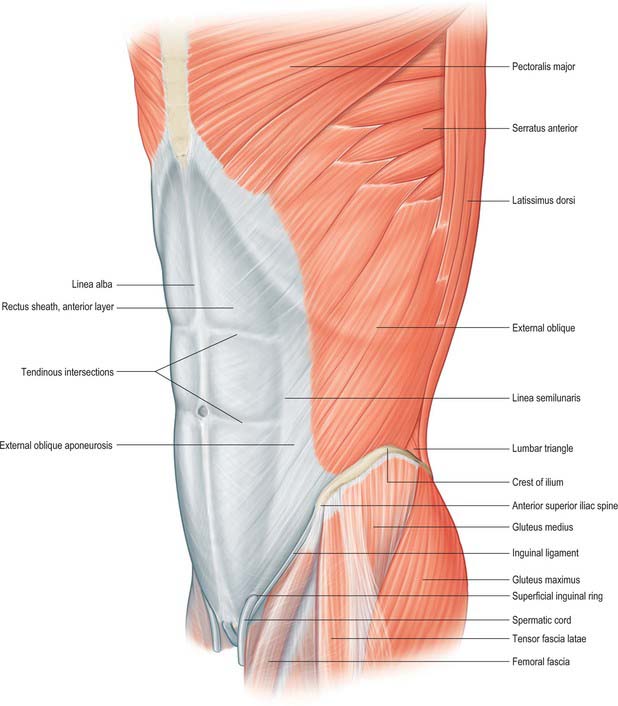

The anterior abdominal wall extends from the costal margins and xiphoid process superiorly to the iliac crests, pubis and pubic symphysis inferiorly. It overlaps and is connected to both the posterior abdominal wall and paravertebral tissues. It forms a continuous but flexible sheet of tissue across the anterior and lateral aspects of the abdomen. The anterior abdominal wall is composed of the integument, muscles and connective tissue lining the peritoneal cavity (Figs 61.1–61.5). It has an important role in maintaining the form of the abdomen and is involved in many physiological activities. Anterior abdominal wall tissues form the inguinal canal that connects the abdominal cavity to the scrotum in men or labia majora in women, and also form the umbilicus; both of these sites are of considerable clinical importance.

SKIN AND SOFT TISSUE

VASCULAR SUPPLY AND LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE

Superior epigastric artery and veins

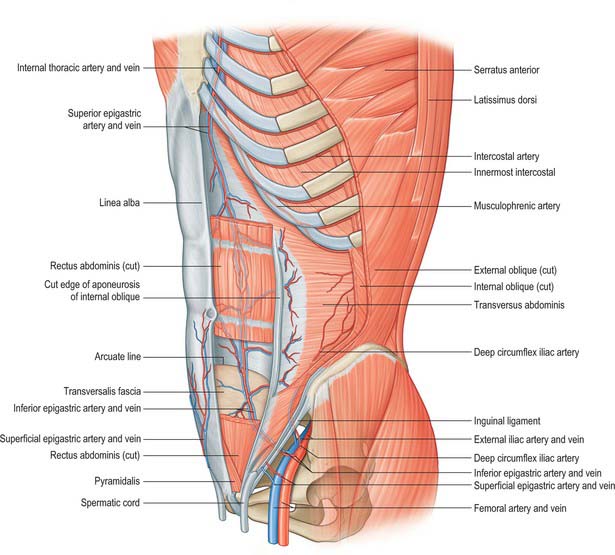

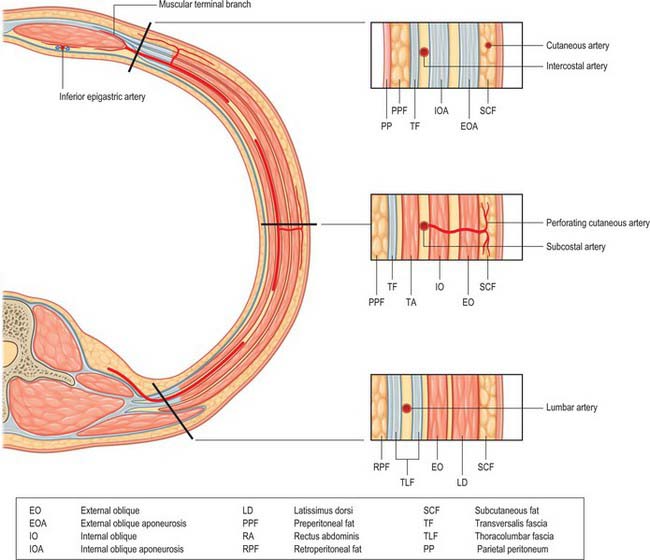

The superior epigastric artery is a terminal branch of the internal thoracic artery. It descends between the costal and xiphoid slips of the diaphragm, accompanied by two or more veins (Fig. 61.4). The vessels pass anterior to the lower fibres of transversus thoracis and the upper fibres of transversus abdominis. The artery enters the rectus sheath behind rectus abdominis and runs down to anastomose with the inferior epigastric artery usually above the level of the umbilicus. Branches supply rectus abdominis and perforate the sheath to supply the abdominal skin. A branch given off in the upper rectus sheath passes anterior to the xiphoid process of the sternum and anastomoses with the same contralateral branch. This vessel may give rise to troublesome bleeding during surgical incisions that extend up to and alongside the xiphoid process. The superior epigastric artery supplies small branches to the anterior part of the diaphragm. On the right, small branches reach the falciform ligament, where they anastomose with branches arising from the hepatic artery.

Inferior epigastric artery and veins

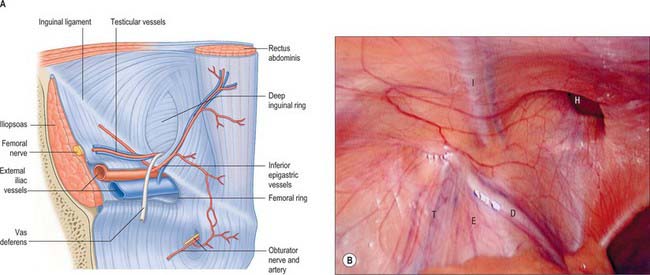

The inferior epigastric artery originates from the external iliac artery posterior to the inguinal ligament (Fig. 61.6). Its accompanying veins, usually two, drain into the external iliac vein. It curves forwards in the anterior extraperitoneal tissue and ascends obliquely along the medial margin of the deep inguinal ring. It lies posterior to the spermatic cord, but is separated from it by the transversalis fascia. It pierces the transversalis fascia which forms the flimsy posterior support of rectus abdominis, and ascends between the muscle and the fascia and overlying pre-peritoneal connective tissue. In this part of its course, it raises the parietal peritoneum of the anterior abdominal wall as the lateral umbilical fold but has little supporting tissue posteriorly. Disruption of the artery, by surgical incisions e.g. for laparoscopic ports or drains, is not uncommon and the resulting haematoma may expand to considerable size because of the lack of tissue against which the bleeding is effectively compressed. The artery divides into numerous branches. Those which anastomose with branches of the superior epigastric artery do so posterior to rectus abdominis at a variable height above the umbilicus. The inferior epigastric vessels are usually significantly larger than the superior vessels and provide the ‘dominant’ supply to rectus abdominis. Preparatory ligation of the inferior epigastric artery is often performed for myo(cutaneous) flaps using the mid or lower rectus abdominis based on the superior epigastric artery to allow expansion of the superior arterial flow to improve viability of the flap. Branches anastomose with terminal branches of the lower six posterior intercostal arteries posterior to rectus abdominis at the lateral border close to the sheath. The artery is an important inferomedial relation of the deep inguinal ring, and may be damaged during extensive medial dissection of the deep ring during hernia repair, particularly when this is performed in the preperitoneal plane. The vas deferens in the male, or round ligament in the female, wind laterally round it. It has the following branches: the cremasteric artery, a pubic branch, and muscular and cutaneous branches.

The cremasteric artery accompanies the spermatic cord in males and supplies the cremaster and other coverings of the cord. It anastomoses with the testicular artery. In females it is small and accompanies the round ligament. A pubic branch, near the femoral ring, descends posterior to the pubis and anastomoses with the pubic branch of the obturator artery. Occasionally, the pubic branch of the inferior epigastric artery is larger than the main obturator artery origin, and it supplies the majority of flow into the obturator artery in the thigh. It is then referred to as the aberrant obturator artery. It lies close to the medial border of the femoral ring and may be damaged in medial dissection of the ring during femoral hernia repair. Muscular branches supply the abdominal muscles and peritoneum, and anastomose with the circumflex iliac and lumbar arteries. Cutaneous branches perforate the aponeurosis of external oblique, supply the skin and anastomose with branches of the superficial epigastric artery.

Posterior intercostal, subcostal and lumbar arteries

The 10th and 11th posterior intercostal arteries and the subcostal artery emerge from under the subcostal groove of their respective ribs and pass into the tissues of the anterior abdominal wall. They run through the aponeurosis of transversus abdominis and lie deep to the fibres of internal oblique. The lumbar arteries also cross the aponeurosis of transversus abdominis and lie deep to internal oblique. The arteries on either side run forward, giving off muscular branches to the overlying internal and external oblique, before anastomosing with the lateral branches of the superior and inferior epigastric arteries at the lateral border of the rectus sheath (Fig. 61.7). Perforating cutaneous vessels run vertically through the muscles to supply the overlying skin and subcutaneous tissue. A small contribution to the supply of the lower abdominal muscles comes from branches of the deep circumflex iliac arteries.

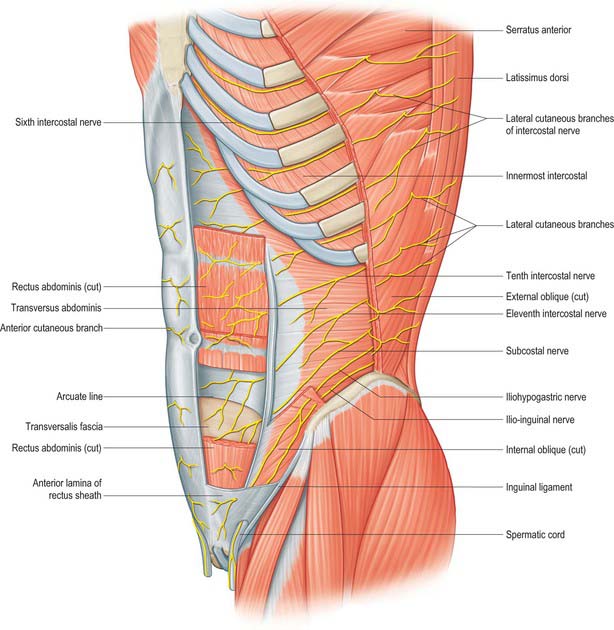

SEGMENTAL NERVES

The seventh to the 12th lower thoracic ventral rami continue anteriorly from the intercostal spaces into the abdominal wall (Fig. 61.3). Approaching the anterior ends of their respective spaces, the seventh and eighth nerves curve superomedially across the deep surface of the costal cartilages between the digitations of transverse abdominis. They reach the deep aspect of the posterior layer of the aponeurosis of internal oblique. Both the seventh and eighth nerves then run through this aponeurosis, pass posterior to rectus abdominis and supply branches to the upper portion of the muscle. They pass through the muscle near its lateral edge and pierce the anterior rectus sheath to supply the skin of the epigastrium.

The ninth to 11th intercostal nerves pass from their intercostal spaces between digitations of the diaphragm and transversus abdominis. They enter the layer between transversus abdominis and internal oblique. Here, the ninth nerve runs forwards almost horizontally, whereas the tenth and 11th pass inferomedially. At the lateral edge of rectus abdominis, the nerves pierce the posterior layer of the aponeurosis of internal oblique and pass behind the muscle to end, like the seventh and eighth intercostal nerves, with cutaneous branches. The ninth nerve supplies skin above the umbilicus, the tenth supplies skin, which includes the umbilicus, and the 11th supplies skin below the umbilicus (see Fig. 15.12 and Chapters 42, 45 and 79). The 12th thoracic nerve (subcostal nerve) connects with the first lumbar ventral ramus (dorsolumbar nerve). It accompanies the subcostal vessels along the inferior border of the 12th rib, passing behind the lateral arcuate ligament and kidney and anterior to the upper part of the quadratus lumborum. It perforates the transversus abdominis fascia, running deep to the internal oblique, to be distributed like the lower intercostal nerves. It supplies the anterior gluteal skin reaching down to the greater trochanter.

MUSCLES

ANTEROLATERAL MUSCLES OF THE ABDOMEN

Rectus abdominis, pyramidalis, external oblique, internal oblique and transversus abdominis constitute the anterolateral muscles of the abdomen. They act together to perform a range of functions, some of which involve the generation of a positive pressure within one or more body cavities. Although many of these activities may occur with no ‘forced assistance’, activities such as expiration, defecation and micturition may be aided by the generation of a positive intra-abdominal pressure. Parturition, coughing and vomiting always require such a positive pressure. Under resting conditions, the tone developed within the muscles provides support for the abdominal viscera and retains the normal contour of the abdomen. The consequences of lack of muscular support can be seen in conditions such as ‘prune belly syndrome’, where there is congenital absence of these muscles.

Rectus abdominis

Rectus abdominis is a long, strap-like muscle that extends along the entire length of the anterior abdominal wall. It is widest in the upper abdomen and lies just to the side of the midline. The paired recti are separated in the midline by the linea alba (Fig. 61.4).

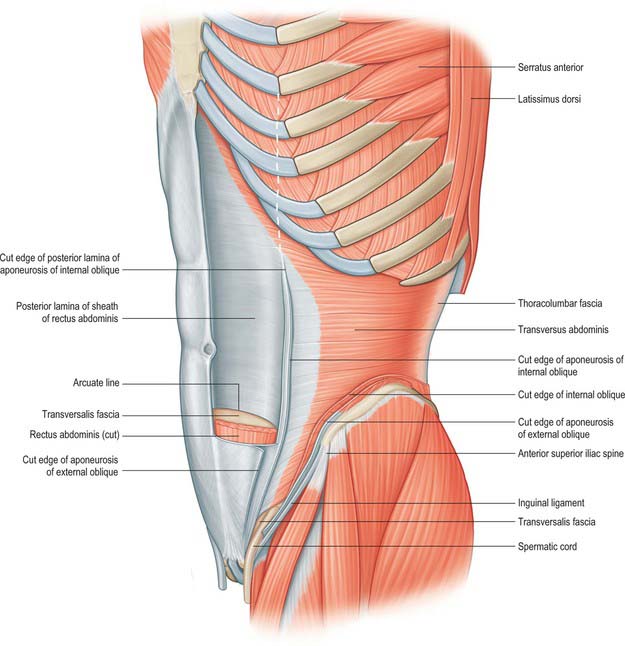

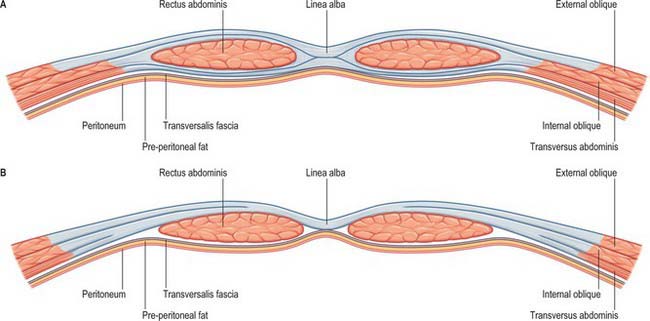

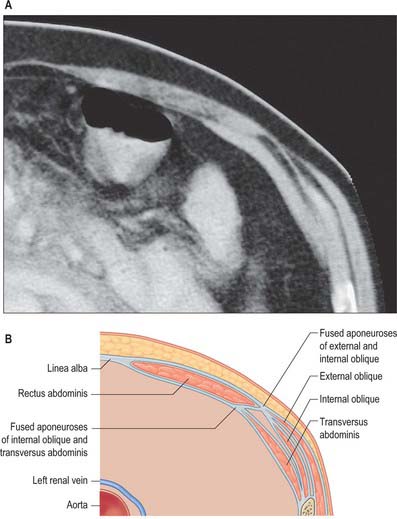

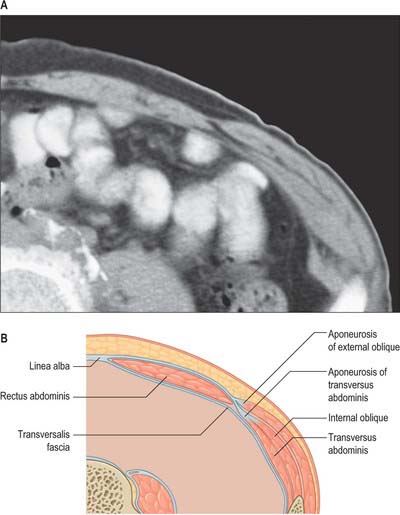

Rectus sheath

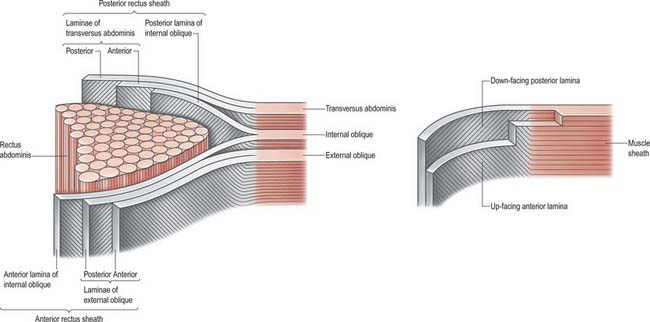

Rectus abdominis on each side is enclosed by a fibrous sheath. The anterior portion of this sheath extends the entire length of the muscle and fuses with the periosteum of the muscle attachments. Posteriorly, the sheath is complete in the upper two-thirds of the muscle. In the lower one-third, the posterior layer of the sheath stops approximately midway between the umbilicus and the pubis. In most individuals this is a clearly defined line, although the transition may not always be clear-cut in others. The lower border of the posterior sheath is called the arcuate line. Below this level, rectus abdominis is enclosed posteriorly by the transversalis fascia and extraperitoneal connective tissue (Figs 61.8 and 61.9). The rectus sheath is formed from decussating fibres from all three lateral abdominal muscles. External oblique, internal oblique and transversus abdominis each forms a bilaminar aponeurosis at their medial borders. The fibres from all three anterior leaves run obliquely upwards, whereas the posterior leaves run obliquely downwards at right angles to the anterior leaves.

The anterior rectus sheath is composed of both leaves of the aponeurosis of external oblique and the anterior leaf of the aponeurosis of internal oblique fused together. The posterior rectus sheath is composed of the posterior leaf of the aponeurosis of internal oblique and both leaves of the aponeurosis transversus abdominis (Fig. 61.10). Because of this arrangement, both the anterior and posterior layers of the rectus sheath consist of three layers of fibres with the middle layer running obliquely at right angles to the other two. At the midline, the anterior and posterior layers are closely approximated. Fibres of each layer decussate to the opposite side of the sheath, forming a continuous aponeurosis with the contralateral muscles (Fig. 61.11). Fibres also decussate anteroposteriorly, crossing from anterior sheath to posterior sheath. The dense fibrous line caused by this decussation is called the linea alba. The external oblique, internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles can thus be regarded as paired, digastric muscles with a central tendon in the form of the linea alba. These decussating fibres maybe used to identify the midline during surgical incisions, since they can be seen as oblique fibres crossing at right angles. Below the level of the arcuate line, the fibres forming the posterior rectus sheath rapidly cease running behind the rectus and all leaves pass into the anterior rectus sheath.

Linea alba

The linea alba is a tendinous raphe extending from the xiphoid process to the symphysis pubis and pubic crest. It lies between the two recti and is formed by the interlacing and decussating aponeurotic fibres of external oblique, internal oblique and transversus abdominis. It is visible only in the lean and muscular, as a slight groove in the anterior abdominal wall. A fibrous cicatrix, the umbilicus, lies a little below the midpoint of the linea alba, and is covered by an adherent area of skin. Below the umbilicus, the linea alba narrows progressively as the rectus muscles lie closer together. Above the umbilicus, the rectus muscles diverge from one other and the linea alba is correspondingly broader. The linea alba has two attachments at its lower end: its superficial fibres are attached to the symphysis pubis, and its deeper fibres form a triangular lamella that is attached behind rectus abdominis to the posterior surface of the pubic crest on each side. This posterior attachment of linea alba is named the ‘adminiculum lineae albae’. The linea alba is crossed from side to side by a few minute vessels.

External oblique

External oblique is the largest and the most superficial of the three lateral abdominal muscles (Fig. 61.1). It curves around the lateral and anterior parts of the abdomen and is attached to the external surfaces and inferior borders of the lower eight ribs. The attachments rapidly become muscular and interdigitate with the lower attachment of serratus anterior and latissimus dorsi along an oblique line that extends downwards and backwards. The upper attachments are close to the cartilages of the corresponding ribs, the middle ones arise from the ribs at some distance from their cartilages and the lowest are close to the apex of the cartilage of the 12th rib. The fibres of external oblique diverge as they pass to their lower attachments. Those from the lower two ribs pass nearly vertically downwards and are attached to the anterior half or more of the outer lip of the anterior segment of the iliac crest. The middle and upper fibres pass downwards and forwards and end in the anterior aponeurosis, along a line drawn vertically from the ninth costal cartilage to a little below the level of the umbilicus. The muscle fibres rarely descend beyond a line from the anterior superior iliac spine to the umbilicus. The posterior border of the muscle is free.

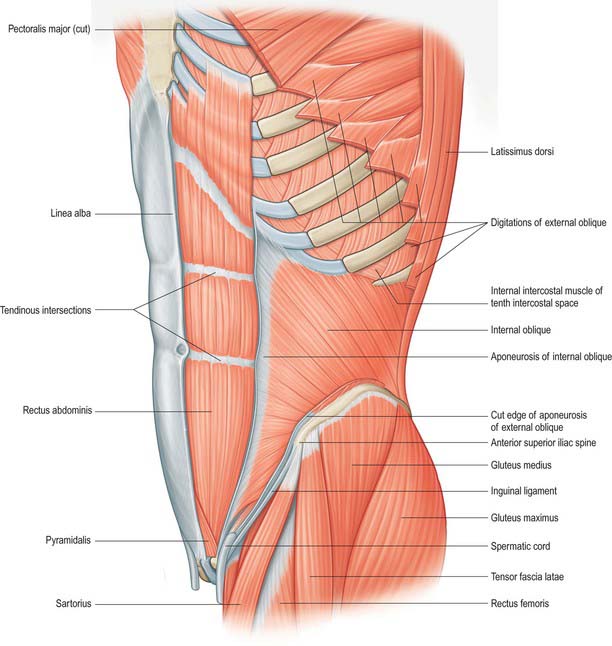

Internal oblique

Internal oblique lies deep to external oblique for the majority of its course (Fig. 61.2). It is thinner and less bulky than external oblique. Its fibres arise from the lateral two-thirds of the grooved upper surface of the inguinal ligament, where they form a common attachment with the iliac fascia to the inguinal ligament. Laterally, internal oblique is also attached to the anterior two-thirds of the intermediate line of the anterior segment of the iliac crest, and posteriorly some fibres are attached to the thoracolumbar fascia. The fibres originating from the posterior end of the iliac attachment pass upwards and laterally and are attached to the inferior borders and tips of the lower three or four ribs and their cartilages. Here, the attachments merge with those of the internal intercostals. The uppermost of these fibres form a short, free superior border. The fibres attached to the anterior iliac crest diverge and end in the anterior aponeurosis, which gradually broadens from below upwards. The uppermost part of the aponeurosis is attached to the cartilages of the seventh, eighth and ninth ribs. The fibres that originate from the inguinal ligament arch downwards and medially across the spermatic cord in the male and the round ligament of the uterus in the female. They become tendinous, fuse with the corresponding part of the aponeurosis of transversus abdominis, and attach to the crest and medial part of the pectineal line, forming the conjoint tendon.

Cremaster

Transversus abdominis

Transversus abdominis is the deepest of the lateral abdominal muscles (Fig. 61.5). It is attached to the lateral one-third of the inguinal ligament and the associated iliac fascia, the anterior two-thirds of the inner lip of the anterior segment of the iliac crest, the thoracolumbar fascia between the iliac crest and the 12th rib, and the internal aspects of the lower six costal cartilages. The costal attachments interdigitate with the attachment of the diaphragm. The muscle ends in an anterior aponeurosis. The lower fibres curve downwards and medially, together with those of the aponeurosis of internal oblique, and insert into the pubic crest and pectineal line to form the conjoint tendon. A band of fibres, sometimes muscular, may run from the lower border of the muscle to the inguinal ligament and is called the inter-foveolar ligament. The remainder of the aponeurosis passes medially and the fibres decussate at, and blend with, the linea alba. The upper costal and anterior iliac fibres of transversus abdominis are short. The lower costal and posterior iliac fibres are longer, and the thoracolumbar fibres are longest. Near the xiphoid process, the aponeurosis is formed only 2–3 cm from the linea alba, so the muscular part of transversus abdominis extends behind rectus into the posterior layer of the rectus sheath. The medial edge of the muscle, at the start of the aponeurosis, curves first downwards and laterally, and is furthest from the lateral edge of the rectus sheath at the level of the umbilicus. It then curves downwards and medially towards the middle of the superior crus of the superficial inguinal ring.

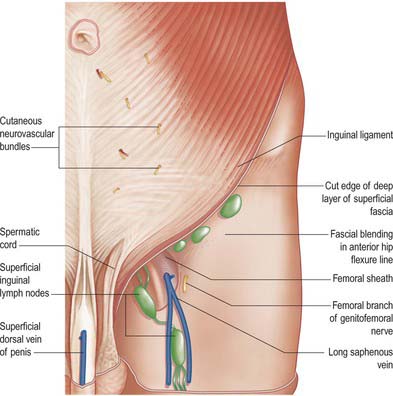

Inguinal canal

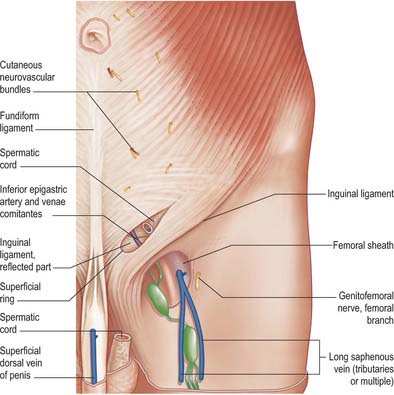

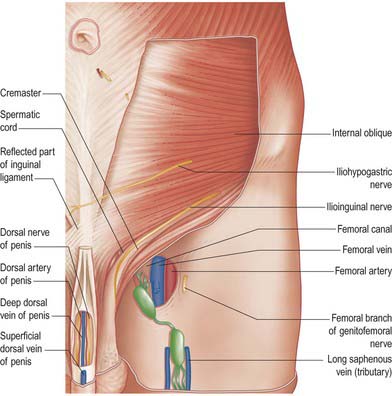

The inguinal canal is a natural hiatus in the tissues of the anterior abdominal wall, and is formed from the various layers of the wall in the region of the groin (Figs 61.12, 61.13, 61.14, 61.15, and see Fig. 76.2). Its size and form vary with age, and although it is present in both sexes it is most well developed in the male. The canal is an oblique tunnel, with deep and superficial openings or rings. It contains the spermatic cord in males, the round ligament of the uterus in females, and the ilioinguinal nerve in both sexes.

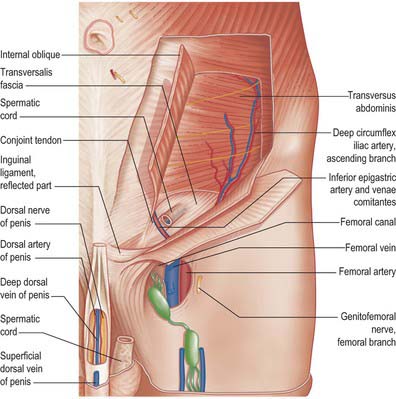

Fig. 61.15 Dissection of the regions shown in Fig. 61.13, with parts of external and internal oblique muscles removed.

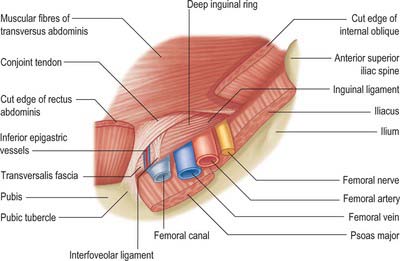

Deep inguinal ring

The deep inguinal ring is situated in the transversalis fascia, midway between the anterior superior iliac spine and the symphysis pubis approximately 1.25 cm above the inguinal ligament. It is oval, with an almost vertical long axis. Its size varies between individuals, and it is always much larger in the male. It is related above to the arched lower margin of transversus abdominis, and medially to the inferior epigastric vessels and the interfoveolar ligament, when that is present. Traction on the fascial ring exerted by internal oblique may constitute a valve-like safety mechanism when intra-abdominal pressure is increased.

Relations

The inferior epigastric vessels are important posterior relations of the medial end of the canal (Fig. 61.16). They lie on the transversalis fascia as they ascend obliquely behind the conjoint tendon into the posterior portion of the rectus sheath.

HERNIAS OF THE ANTERIOR ABDOMINAL WALL

INGUINAL HERNIA

Cormack GC, George B, Lamberty H. The Arterial Anatomy of Skin Flaps, 2nd edn., London, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1994:168-172.

Lytle WJ. Inguinal anatomy. J Anat. 1979;128:581-594.

Rizk NN. A new description of the anterior abdominal wall in man and mammals. J Anat. 1980;131:373-385.

Shafik A. The cremasteric muscle. In: Johnson AD, Gomes WR. The Testis. New York: Academic Press, 1977.