Chapter 13 Antepartum haemorrhage

Antepartum haemorrhage is defined as significant bleeding from the birth canal occurring after the 20th week of pregnancy. The causes and proportions of cases of antepartum haemorrhage are shown in Table 13.1. In fewer than 0.05% of cases the bleeding is due to a cervical lesion, such as a cervical polyp, or rarely, a cervical carcinoma.

Table 13.1 The incidence of the causes of antepartum haemorrhage

| INCIDENCE (%) | |

|---|---|

| Placenta praevia | 0.5 |

| Placental abruption | |

| Mild or indeterminate | 3.0 |

| Moderate grade | 0.8 |

| Severe grade | 0.2 |

| Cervical bleeding | 0.05 |

PLACENTA PRAEVIA

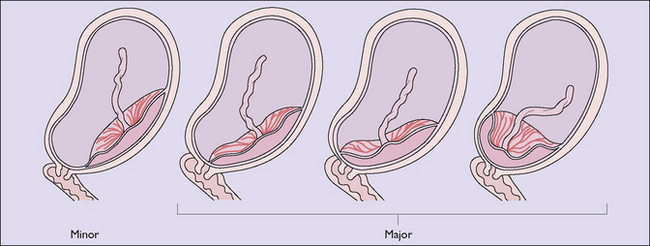

In this condition the placenta is implanted, either partially or wholly, in the lower uterine segment and lies below (praevia) the fetal presenting part. The extent of implantation may be minor, in which case vaginal birth is possible, or major, when it is not (Fig. 13.1).

Symptoms, signs and diagnosis

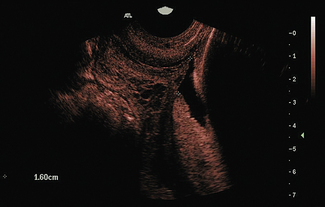

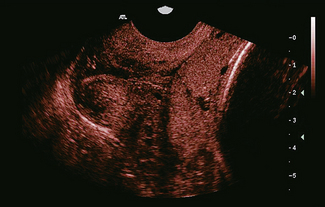

The bleeding is painless, causeless and recurrent. The presenting part is usually high and often not central to the pelvic brim. The diagnosis is made should an ultrasound image show that the placenta is praevia (Figs 13.2, 13.3).

PLACENTAL ABRUPTION (ACCIDENTAL HAEMORRHAGE)

Signs, symptoms and treatment of antepartum haemorrhage

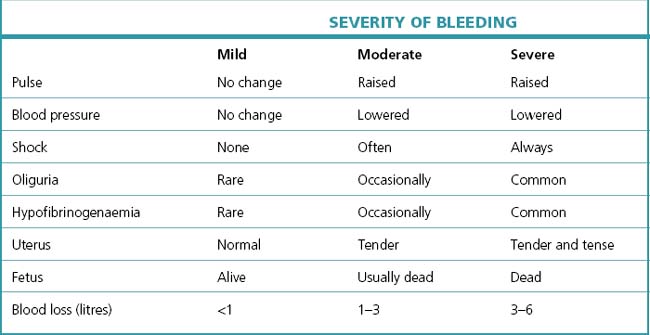

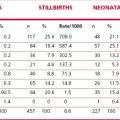

The symptomatology is related to the degree of bleeding and the extent of placental detachment (Table 13.2).