Chapter 7 Antepartum Care

PRECONCEPTION AND PRENATAL CARE, GENETIC EVALUATION AND TERATOLOGY, AND ANTENATAL FETAL ASSESSMENT

Preconception Care

Preconception Care

Several models of preconception care have been developed. Major components of preconception care include risk assessment, health promotion, and medical and psychosocial interventions and follow-up, as summarized in Table 7-1. There is currently no consensus on the timing of preconception care, probably because there are different ideas about what preconception care should be or do. For some, preconception care means a single prepregnancy checkup a few months before couples attempt to conceive. A single visit, however, may be too little too late to address some problems (e.g., promoting smoking cessation or healthy weight) and will miss those pregnancies that are unintended at the time of conception (about half of all pregnancies in the United States). For others, preconception care means all well-woman care, from prepubescence to menopause. In practice, however, asking providers to squeeze more into an already hurried routine visit may not be feasible, and some components (e.g., genetic screening or laboratory testing) may not be indicated for every woman at every visit.

| Major Components of Preconception Care | Risk Assessment |

|---|---|

| Reproductive life plan | Ask your patient if she plans to have any (more) children and how long she plans to wait until she (next) becomes pregnant. Help her develop a plan to achieve those goals. |

| Past reproductive history | Review prior adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as fetal loss, birth defects, low birth weight, and preterm birth, and assess ongoing biobehavioral risks that could lead to recurrence in a subsequent pregnancy. |

| Past medical history | Ask about past medical history such as rheumatic heart disease, thromboembolism, or autoimmune diseases that could affect future pregnancy. Screen for ongoing chronic conditions such as hypertension and diabetes. |

| Medications | Review current medication use. Avoid category X drugs and most category D drugs unless potential maternal benefits outweigh fetal risks (see Box 7-1). Review use of over-the-counter medications, herbs, and supplements. |

| Infections and immunizations | Screen for periodontal, urogenital, and sexually transmitted infections as indicated. Discuss TORCH (toxoplasmosis, other, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes) infections and update immunization for hepatitis B, rubella, varicella, Tdap (combined tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis), human papillomavirus, and influenza vaccines as needed. |

| Genetic screening and family history | Assess risk for chromosomal or genetic disorders based on family history, ethnic background, and age. Offer cystic fibrosis screening. Discuss management of known genetic disorders (e.g., phenylketonuria, thrombophilia) before and during pregnancy. |

| Nutritional assessment | Assess anthropometric (body mass index), biochemical (e.g., anemia), clinical, and dietary risks. |

| Substance abuse | Ask about smoking, alcohol, drug use. Use T-ACE (tolerance, annoyed, cut down, eye opener) or CAGE (cut-down, annoyed, guilty, eye-opener) questions to screen for alcohol and substance abuse. |

| Toxins and teratogens | Review exposures at home, neighborhood, and work. Review Material Safety Data Sheet and consult local Teratogen Information Service as needed. |

| Psychosocial concerns | Screen for depression, anxiety, intimate-partner violence, and major psychosocial stressors. |

| Physical examination | Focus on periodontal, thyroid, heart, breasts, and pelvic examination. |

| Laboratory tests | Check complete blood count, urinalysis, type and screen, rubella, syphilis, hepatitis B, HIV, cervical cytology; screen for gonorrhea, chlamydia, and diabetes in selected populations. Consider thyroid-stimulating hormone. |

| Major Components of Preconception Care | Health promotion |

| Family planning | Promote family planning based on a woman’s reproductive life plan. For women who are not planning on getting pregnant, promote effective contraceptive use and discuss emergency contraception. |

| Healthy weight and nutrition | Promote healthy prepregnancy weight through exercise and nutrition. Discuss macronutrients and micronutrients, including 5-a-day and daily intake of multivitamin containing folic acid. |

| Health behaviors | Promote such health behaviors as nutrition, exercise, safe sex, effective use of contraception, dental flossing, and use of preventive health services. Discourage risk behaviors such as douching, nonuse of seat belt, smoking, and alcohol and substance abuse. |

| Stress resilience | Promote healthy nutrition, exercise, sleep, and relaxation techniques; address ongoing stressors such as intimate partner violence; identify resources to help patient develop problem-solving and conflict resolution skills, positive mental health, and relational resilience. |

| Healthy environments | Discuss household, neighborhood, and occupational exposures to metals, organic solvents, pesticides, endocrine disruptors, and allergens. Give practical tips such as how to reduce exposures during commuting or picking up dry cleaning. |

Prenatal Care

Prenatal Care

THE FIRST PRENATAL VISIT

Standardized forms have been developed to facilitate overall prenatal risk assessment. One such system is the Problem Oriented Prenatal Risk Assessment System, or POPRAS (www.POPRAS.com).

Prenatal laboratory testing should be undertaken as outlined in Table 7-1, if not done during preconception care. Screening for and treating asymptomatic bacteriuria significantly reduces the risk for pyelonephritis and preterm delivery.

Confirming Pregnancy and Determining Viability

Confirming Pregnancy and Determining Viability

TYPES OF SPONTANEOUS ABORTION

ETIOLOGY

General Maternal Factors

Three medical disorders are commonly linked to spontaneous abortion: (1) diabetes mellitus, (2) hypothyroidism, and (3) systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The evidence linking diabetes mellitus with spontaneous abortion is not conclusive, and severe hypothyroidism is more often associated with disordered ovulation than spontaneous abortion. Up to 40% of clinical pregnancies are lost in women with SLE, and such patients have an increased risk for pregnancy loss before developing the clinical stigmata of the disease (see Chapter 16).

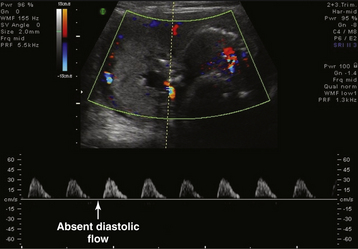

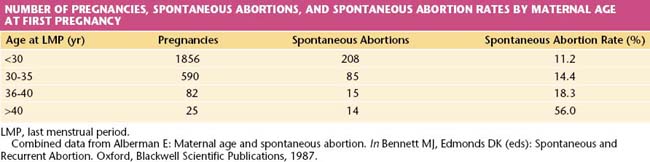

The risk for abortion increases with maternal age (Table 7-2). If a live fetus is demonstrated by ultrasonography at 8 weeks’ gestational age, however, fewer than 2% will abort spontaneously when the mother is younger than 30 years of age. If she is older than 40 years, the risk exceeds 10%, and it may be as high as 50% at age 45 years. The probable explanation is the increased incidence of chromosomally abnormal conceptus in older women.

Immunologic Factors

A successful pregnancy depends on a number of immunologic factors that allow the host (mother) to retain an antigenically foreign product (fetus) without rejection taking place (see Chapter 6). The precise mechanism of this immunologic anomaly is not fully understood, but the immunologic functioning of some women, particularly those who abort recurrently, is different from that of women who carry pregnancies to term. The immunologic relationship between male and female in such a couple may be regarded as abnormal, and in some instances, treatment of this condition may result in a successful pregnancy.

MANAGEMENT

Recurrent Abortion

More than half of couples with recurrent losses will have normal findings during an evaluation. When a specific etiologic factor is found, appropriate management often leads to reproductive success. Many of the congenital abnormalities of the uterus can now be diagnosed using pelvic ultrasonography and may no longer require laparotomy for repair. Cervical incompetence is managed by the placement of a cervical suture (cerclage) at the level of the internal os, and this suture is best placed in the first trimester, after a live fetus has been demonstrated on ultrasonography. The effectiveness of prophylactic cervical cerclage (see Chapters 17 and 19) in preventing recurrent loss from cervical incompetence has not been conclusively established.

Patients Who Require Genetic Counseling

Patients Who Require Genetic Counseling

Ideally, couples should receive preconception counseling before they decide to have children, so that genetic disease in the couple or their families may be identified before pregnancy. The major reason couples are referred for prenatal diagnosis is advanced maternal age. Women older than 34 years have an increased risk for having children with chromosomal abnormalities. Other indications for genetic counseling and prenatal diagnosis are listed in Box 7-2.

BOX 7-2 Indications for Genetic Counseling and Prenatal Diagnosis Other than Age

CONGENITAL AND HEREDITARY DISORDERS

Chromosomal Disorders

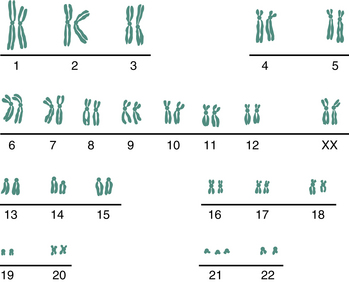

Chromosomal abnormalities occur in 0.5% of live births, but the incidence associated with spontaneous abortions is much higher and is estimated to be about 50%. The most common chromosomal abnormalities among liveborn infants are sex chromosomal aneuploidy (e.g., Turner syndrome [45 XO], Klinefelter syndrome [47 XXY]), balanced Robertsonian translocations (translocations within group D or between groups D and G), and autosomal trisomies (e.g., Down syndrome; Figure 7-1).

Women older than 34 years are at increased risk for giving birth to children with autosomal trisomies (e.g., trisomy 21, 13, or 18) or sex chromosomal abnormalities (e.g., triple X syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome). The overall risk for Down syndrome (trisomy 21) is 1 per 800 live births. It increases to about 1 per 300 live births for women who are 35 to 39 years of age and to about 1 in 80 for those 40 to 45 years of age (Table 7-3). The incidence of Down syndrome diagnosed at the time of chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis is considerably higher. In women 35 to 39 years of age, the rate is about 1 in 125; in those 40 to 45, it is about 1 in 20. The discrepancy between the rate of occurrence at delivery and that at prenatal diagnosis is believed to be due in part to fetal loss in the second and third trimester.

TABLE 7-3 RISK TABLE FOR CHROMOSOMAL ABNORMALITIES BY MATERNAL AGE AT TERM

| Age at Term (yr) | Risk for Trisomy 21∗ | Risk for Any Chromosomal Abnormality†,‡ |

|---|---|---|

| 15 | 1:1578 | 1:454 |

| 16 | 1:1572 | 1:475 |

| 17 | 1:1565 | 1:499 |

| 18 | 1:1556 | 1:525 |

| 19 | 1:1544 | 1:555 |

| 20 | 1:1528 | 1:525 |

| 21 | 1:1507 | 1:525 |

| 22 | 1:1481 | 1:499 |

| 23 | 1:1447 | 1:499 |

| 24 | 1:1404 | 1:475 |

| 25 | 1:1351 | 1:475 |

| 26 | 1:1286 | 1:475 |

| 27 | 1:1208 | 1:454 |

| 28 | 1:1119 | 1:434 |

| 29 | 1:1018 | 1:416 |

| 30 | 1:909 | 1:384 |

| 31 | 1:796 | 1:384 |

| 32 | 1:683 | 1:322 |

| 33 | 1:574 | 1:285 |

| 34 | 1:474 | 1:243 |

| 35 | 1:384 | 1:178 |

| 36 | 1:307 | 1:148 |

| 37 | 1:242 | 1:122 |

| 38 | 1:189 | 1:104 |

| 39 | 1:146 | 1:80 |

| 40 | 1:112 | 1:62 |

| 41 | 1:85 | 1:48 |

| 42 | 1:65 | 1:38 |

| 43 | 1:49 | 1:30 |

| 44 | 1:37 | 1:23 |

| 45 | 1:28 | 1:18 |

| 46 | 1:21 | 1:14 |

| 47 | 1:15 | 1:10 |

| 48 | 1:11 | 1:8 |

| 49 | 1:8 | 1:6 |

| 50 | 1:6 | Data not available |

∗ Data from Chuckle HA, Wald NJ, Thompson SC: Estimating a woman’s risk of having a pregnancy associated with Down’s syndrome using her age and serum alpha-fetoprotein level. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 94:387, 1987.

† Adapted from Hook EB: Rates of chromosomal abnormalities at different maternal ages. Obstet Gynecol 58:282-285, 1981.

‡ Risk for any chromosomal abnormality includes the risk for trisomy 21 and 18 in addition to trisomy 13, 47 XXY, 47 XYY, Turner syndrome genotype, and other clinically significant abnormalities. 47 XXX is not included.

Autosomal Recessive Disorders

Autosomal Recessive Disorders

GENETIC SCREENING FOR AUTOSOMAL RECESSIVE DISORDERS

Carrier screening programs for autosomal recessive disorders have traditionally focused on high-risk populations, in which the frequency of heterozygotes is greater than in the general population. Screening for Tay-Sachs disease among Eastern European Jewish and French Canadian populations has proved to be particularly successful in the recognition of couples at 25% risk for having offspring affected with this fatal disease. Table 7-4 lists selected autosomal recessive disorders for which genetic screening has been initiated.

TABLE 7-4 SELECTED AUTOSOMAL RECESSIVE DISEASES IN DEFINED ETHNIC GROUPS

| Disease | Ethnic Group | Carrier Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Sickle cell disease | Blacks | 1/10 |

| Cystic fibrosis | Whites | 1/25 |

| Tay-Sachs disease | Jews, French Canadians | 1/30 |

| Thalassemia | Mediterraneans, Southeast Asians | 1/25 |

Maternal Ultrasonic and Serum Marker Screening

Maternal Ultrasonic and Serum Marker Screening

FIRST-TRIMESTER SCREENING

A combination of maternal age, fetal nuchal translucency (NT) thickness, and maternal serum-free β-human chorionic gonadotrophin (β-hCG) and pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A (PAPP-A) are included in the first-trimester screen. Maternal age alone has only a 30% detection rate. In the early 1990s, an association was reported between fetal chromosomal abnormalities and the finding of an abnormally increased nuchal translucency (an echo-free area at the back of the fetal neck) between 10 and 14 weeks’ gestational age (Figure 7-2). Increased nuchal translucency has been associated with both chromosomal abnormalities and other congenital anomalies. Elevated levels of free β-hCG and low levels of plasma protein-A are associated with an increased risk for Down syndrome. A multicenter study in the United States reported that combining first-trimester maternal serum screening markers with nuchal translucency and maternal age showed a detection rate for Down syndrome of 79% with a positive screening rate of 5%. Anatomic and radiographic studies have shown absence or hypoplasia of the nasal bones in fetuses with Down syndrome. Visualization of the nasal bone on first-trimester ultrasound has been shown to reduce the risk for Down syndrome (see Figure 7-1), whereas nonvisualization (absence) has been associated with increased risk. The addition of nasal bone assessment to nuchal lucency measurement and serum biochemistry can increase the Down syndrome detection rate to 93% with a screen positive rate of 5%.

Diagnostic Procedures

Diagnostic Procedures

Recombinant DNA technology, coupled with first-trimester fetal tissue sampling, has enhanced the growth and development of prenatal diagnosis. Obstetric procedures, such as ultrasonography, amniocentesis, chorionic villus sampling, and cordocentesis (percutaneous umbilical blood sampling [PUBS]) are currently used during prenatal diagnosis. These procedures are described and discussed in Chapter 17.

Teratology

Teratology

TERATOGENIC AGENTS

Teratogens may be assigned to three broad categories: (1) drugs and chemical agents, (2) infectious agents, and (3) radiation. The list that follows is far from exhaustive. Pharmaceutical agents have their fetal risk classification (as of 2008; see Box 7-1) in parentheses following the drug name.

BOX 7-1 FDA∗ Fetal Drug Risk Classification (approximate percent of drugs in each category)

| Category A (<5%) | Controlled studies in women fail to demonstrate a risk to the fetus in the first trimester. |

| Category B (50%) | Animal-reproduction studies have not demonstrated a fetal risk, but there are no controlled studies in pregnant women. |

| Category C (40%) | Studies in animals have revealed adverse effects on the fetus (teratogenic or embryocidal or other), and there are no controlled studies in women. |

| Category D (<5%) | There is positive evidence of human fetal risk, but the benefits from use in pregnant women may be acceptable despite the risk. |

| Category X (<5%) | Studies in animals or human beings have demonstrated fetal abnormalities, and the risk of the use of the drug in pregnant women clearly outweighs any possible benefit. The drug is contraindicated in women who are or may become pregnant. |

In 2008 the U.S. FDA proposed an overhaul of how pregnancy and breastfeeding information should be included on provider labeling for prescription drugs. The proposed new labeling would eliminate the current lettering system (above), which is not required to be updated as new information becomes available and, according to experts, can be misleading. The proposed new system would provide brief bulleted information instead of a letter designation on the potential benefits and risks for the mother and the fetus and how these risks may change the course of pregnancy. The proposed new system would require drug labels to be updated as new data emerge. The U.S. FDA website (www.fda.gov) should be consulted for the latest information on the new system and on drug risk during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Alcohol

The adverse effects of ethanol (D) on fetal development were not fully realized until the 1970s. The frequency of the fetal alcohol syndrome runs as high as 0.2%, whereas an additional 0.4% of newborns show less severe features of the disorder (Box 7-3).

Anticonvulsants

About 1 in 200 pregnant women is epileptic. Box 7-4 lists the etiologic factors that may play a role in the congenital abnormalities associated with in utero exposure to anticonvulsants. The complexity in providing genetic counseling for pregnant epileptic women is underscored when considering the interactive effects of these factors, the effect of combined anticonvulsant treatment, and the genetic aspects of the disease itself. The goals of counseling include providing the patient with the teratogenic risks of her medication, the risk for seizures during pregnancy, the effect of pregnancy on seizures, and the risk for development of epilepsy in her offspring. From a medication standpoint, the benefits of seizure prevention need to be weighed against the teratogenicity of the drug.

Hormones

DIETHYLSTILBESTROL

Diethylstilbestrol (DES [X]), which in the past was widely used in the treatment of “threatened abortion,” has clearly been established as a fetal teratogen and carcinogen when used in human pregnancy. DES exposure poses an increased risk for cervical abnormalities and uterine malformations (see Figure 19-2) as well as for vaginal clear cell adenocarcinomas in female offspring. Exposed males may be at increased risk for testicular abnormalities, infertility, and testicular malignancy.

Advice during Pregnancy

Advice during Pregnancy

One of the most important functions of prenatal care is to provide information and support to the woman for self-care. The Cochrane pregnancy and childbirth database (www.cochrane.org) has compiled systematic reviews on the effectiveness of advice and interventions during pregnancy and can be a useful source of information for prenatal care providers. The following sections examine advice given on alleviating unpleasant symptoms, nutrition, lifestyle, and breastfeeding.

NUTRITIONAL COUNSELING

Although the nutritional care plan should be individualized, every woman can benefit from nutritional education that includes counseling on weight gain, dietary guidelines, physical activity, avoidance of harmful substances and unsafe foods, and breastfeeding. The appropriate weight gain during pregnancy is listed in Table 7-5. Recommended rates of weight gain per week during the second and third trimesters are 1.1 pound, 0.9 pound, and 0.66 pound for pregnant women who are underweight, normal weight, and overweight, respectively. Inadequate weight gain has been associated with low birth weight, whereas excessive weight gain has been associated with fetal macrosomia and maternal obesity, because of the difficulty of the mother returning to her prepregnancy body weight. Women should avoid fasting (>13 hours without food) or skipping meals. This behavior is associated with accelerated ketosis and a greater risk for preterm delivery. They should have five feedings per day (breakfast, lunch, afternoon snack, dinner, and bedtime snack). Pregnant women should never skip breakfast.

| BMI | Recommended Weight Gain (pounds) | |

|---|---|---|

| Underweight | <19 | 28–40 |

| Normal | 19–25 | 25–35 |

| Overweight | >25 | 15–25 |

LIFESTYLE ADVICE

Travel is acceptable under most circumstances. Prolonged sitting increases the risk for thrombus formation and thromboembolism. Pregnant women should be encouraged to ambulate periodically when taking a long flight or car ride. Support stockings may help reduce lower limb edema and varicose veins. International travel that places the patient at a high risk for infectious disease (such as travel to areas with a high rate of transmission of malaria or typhoid fever) should be avoided, whenever possible. When such travel cannot be avoided, appropriate vaccinations should be administered. For specific recommendations go to www.cdc.gov and select “Traveler’s Health.” Live attenuated virus vaccinations are generally contraindicated in pregnancy, but inactivated virus vaccines may be acceptable.

Assessment of Fetal Well-Being

Assessment of Fetal Well-Being

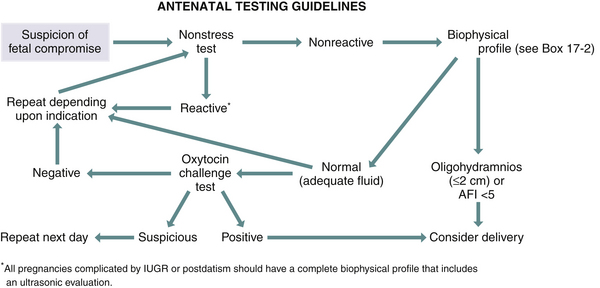

During the past 20 years, electronic advances have provided new technology that has made the fetus more accessible and has allowed visualization of the fetus and recording of intrauterine fetal events. A combination of the nonstress test, contraction stress test, and real-time ultrasonic assessment is used to assess fetal well-being. Figure 7-3 presents an algorithm that may be used to follow a high-risk pregnancy.

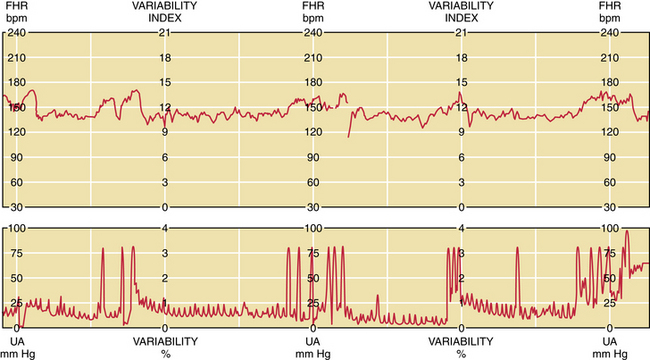

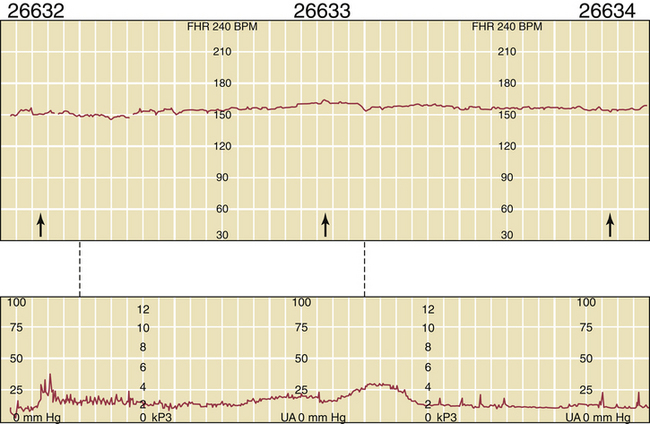

NONSTRESS TEST ASSESSMENT

The first step in the assessment of fetal well-being is the nonstress test. With the mother resting in the left lateral supine position, a continuous fetal heart rate tracing is obtained using external Doppler equipment. The mother reports each fetal movement, and the effects of the fetal movements on heart rate are determined. A normal fetus responds to fetal movement with an acceleration in fetal heart rate of 15 beats/minute or more above the baseline for at least 15 seconds (Figure 7-4). If at least two such accelerations occur in a 20-minute interval, the fetus is regarded as being healthy, and the test is said to be reactive. A nonreactive nonstress test is shown in Figure 7-5.

ULTRASONIC ASSESSMENT

The next step in prenatal assessment is to determine the adequacy of amniotic fluid volume by real-time ultrasonography. Reduced fluid (oligohydramnios) suggests fetal compromise. Oligohydramnios can be defined as an amniotic fluid index (AFI) of less than 5 cm. The AFI represents the sum of the linear measurements (in centimeters) of the largest amniotic fluid pockets noted on ultrasonic inspection of each of the four quadrants of the gestational sac. When amniotic fluid is reduced, the fetus is more likely to become compromised as a result of umbilical cord compression. Excessive amniotic fluid (polyhydramnios; AFI > 23 cm) can be a sign of poor control in a diabetic pregnancy or an indication that the fetus may have an anomaly. Fetal breathing (chest wall movements) and fetal movements (stretching and rotational movements) are also used to assess the fetus. A fetus who has at least 30 breathing movements in 10 minutes or 3 body movements in 10 minutes is considered healthy. A combination of a reactive nonstress test, adequate amniotic fluid, adequate fetal breathing, adequate fetal movements, and adequate tone is frequently referred to as a normal biophysical profile. Each parameter is given a score of 2. A normal profile equals 10. Table 7-6 lists the recommended frequency for biophysical profile testing based on the high-risk condition.

TABLE 7-6 RECOMMENDED FREQUENCY FOR BIOPHYSICAL PROFILE TESTING

| High-Risk Condition | Frequency |

|---|---|

| IUGR | |

| Mild | Weekly |

| Moderate∗ | Twice weekly |

| DIABETES MELLITUS | |

| Class A | Weekly, 37 to 40 wk |

| Twice weekly, beyond 40 wk | |

| Class B and worse | Twice weekly, beginning at 34 wk |

| POST-TERM PREGNANCY | Twice weekly, beginning at 42 wk |

| Decreased fetal movements | Weekly |

| Other high-risk conditions | Weekly |

| Maternal or physician concern | Weekly |

IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction.

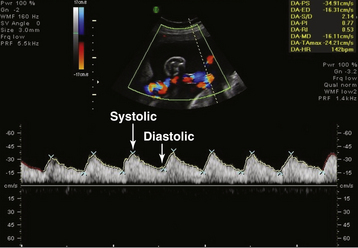

UMBILICAL ARTERY DOPPLER ASSESSMENT

During the ultrasonic assessment, it is easy to assess fetal umbilical artery vascular resistance as an index of fetal health performing pulse wave Doppler assessment. A normal systolic-to-diastolic (S/D) ratio (Figure 7-6) suggests normal flow when the S/D ratio is low, indicating low fetal-placental vascular resistance. When flow becomes abnormal, there is complete loss of flow in the umbilical artery during diastole from the fetus to the placenta (Figure 7-7). When the fetus is very ill, there can be reversed flow during diastole, whereby the deflection during diastole is negative (downward, –cm/second) and blood in the umbilical artery flows backward from the placenta to the fetus in the umbilical artery. Under the latter condition, the fetus should be delivered expeditiously.

FIGURE 7-7 Fetal umbilical artery Doppler assessment at 26 weeks and 5 days in a case with reduced amniotic fluid (small lucent pocket left of midline with Doppler assessment of cord artery). The systolic-to-diastolic ratio cannot be calculated as in Figure 7-6 because of absent diastolic flow. Only systolic flow can be measured (+30 cm/sec).

American Academy of Pediatrics, the American College of Obstetricians, Gynecologists. Guidelines for Perinatal Care, 4th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 1997.

Invasive prenatal testing for fetal aneuploidy. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 88. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:1449-1457.

Liston R., Sawchuck D., Young D. Fetal health surveillance: Antepartum and intrapartum consensus guideline. Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada. British Columbia Prenatal Health Program. [Erratum in J Obstet Gynaecol Can 29:909, 2007.]. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2007;29:S3-S56.

Mennuti M.T. Genetic screening in reproductive health care. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;51:3-33.

Rayburn W.F. What you need to know about medication safety in pregnancy. OBG Management. 2007;19(11):66-82.

Estimating Gestational Age and Date of Confinement

Estimating Gestational Age and Date of Confinement

Sex-Linked Disorders

Sex-Linked Disorders Multifactorial Disorders

Multifactorial Disorders