Chapter 6 Antenatal care

AIMS OF ANTENATAL CARE

The aims of antenatal care are to ensure that:

DIET IN PREGNANCY

Many pregnant women are confused about what they should eat during pregnancy to make sure that they and their baby are properly nourished. What should a pregnant woman eat? To a large extent this will depend on her cultural background, her usual eating behaviour and her income level. As a general principle, women should be advised to eat a well-balanced diet that includes a sufficient amount of each of the five core food groups. It should be low in fat and high in fibre, with sufficient fresh fruit and vegetables, as is suitable for the general population and for her family. Although many women will eat slightly more during pregnancy there is no good evidence that they should drastically alter or increase their food intake. Table 6.1 shows the mean daily intake or RDI (recommended daily intake) that women should try to achieve. Table 6.2 shows what a pregnant woman should try to eat each day, translated into the foods a household buys.

| RDA | See Note | |

|---|---|---|

| Protein | 51 g | * |

| Thiamin | 1.0 mg | * |

| Riboflavin | 1.5 mg | * |

| Niacin | 14–16 mg niacin equivalents | * |

| Vitamin B6 | 1.0–1.5 mg | * |

| Total folate | 400 μg | † |

| Vitamin B12 | 3.0 μg | * |

| Vitamin C | 60 mg | * |

| Zinc | 16 mg | * |

| Iron | 32–36 mg | ‡ |

| Iodine | 150 μg | * |

| Magnesium | 300 μg | * |

| Calcium | 1100 μg | * |

| Phosphorus | 1200 μg | * |

| Selenium | 80 μg | * |

| Vitamin A | 750 μg retinal equivalents | |

| Vitamin E | 7.0 mg α-tocopheral equivalents | |

| Sodium | 920–2300 mg | |

| Potassium | 1950–5460 mg |

* Indicates an increased requirement compared to non-pregnant female 19–54 years

† Daily requirement is doubled to 400 μg daily. RDI = 200 μg in a non-pregnant female 19–54 years

‡ RDI is expressed as a range to account for differences in bioavailability in foods. RDI is for second and third trimesters

| Carbohydrate foods | = | 4–6 servings |

| 1 serving | = | 2 slices bread |

| = | 1 cup cooked rice, pasta, noodles | |

| = | 1 cup porridge or 1⅓ cup cereal flakes | |

| Protein foods | = | 1½ servings |

| 1 serving | = | 100 g cooked meat or chicken |

| = | ½ cup cooked dried beans or peas | |

| = | 2 small eggs | |

| = | 120 g fish fillet or ½ cup tinned fish | |

| = | ⅓ cup nuts | |

| Milk and dairy foods | = | 3 servings |

| 1 serving | = | 250 mL or 1 cup of milk |

| = | 40 g or 2 slices cheese | |

| = | 1 carton/200 g yoghurt | |

| Fruit | = | 4 servings |

| 1 serving | = | 1 piece of fruit |

| = | ½ cup juice | |

| = | 1 cup canned fruit | |

| Vegetables | = | 5–6 servings |

| 1 serving | = | ½ cup cooked vegetables |

| = | 1 cup salad vegetables | |

| = | 1 potato | |

| = | ½ cup cooked dried beans/lentils | |

| Extras | = | 0–2½ servings |

| 1 serving | = | ½ chocolate bar |

| = | 1 slice cake | |

| = | 1 packet chips (crisps) |

Healthy women living in the industrialized countries whose haemoglobin is within the normal range and who eat a sensible diet usually do not require iron supplements. However, many women routinely supplement their diet with iron, as they may find it difficult to eat enough iron-rich foods and are at risk of iron deficiency. A protective factor in pregnancy is that dietary iron absorption is also increased. Iron-rich foods, such as red meat, legumes/pulses, wholegrain breads and cereals and fortified breakfast cereals, should be encouraged as well as including vitamin C-rich foods with those foods containing iron to aid in the absorption of iron. High-risk women in developed countries, such as: women on a limited budget; women with fad food behaviours or eating disorders; vegan/vegetarian women; and most women living in the developing countries require iron supplementation. This is discussed in Chapter 15.

ANTENATAL SCREENING

A great deal of prenatal care is spent in detecting potentially dangerous conditions early; screening is one strategy used. In its simplest form blood pressure measurement is a screening strategy, and is discussed later. Currently, much interest is being shown in screening for congenital defects, such as Down syndrome, neural tube defects and single gene defects, using DNA probes (Box 6.1).

Box 6.1 Possible indications for genetic diagnostic tests in first half of pregnancy

Screening for genetic defects

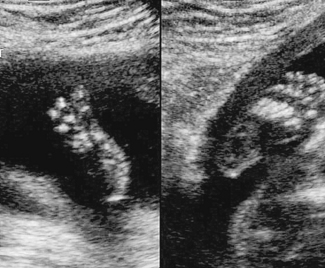

Screening for Down syndrome and certain other genetic defects (for example cystic fibrosis, thalassaemia, haemophilia, Huntington’s disease, some muscular dystrophies) can be carried out by chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis. Before using these methods, an ultrasound examination of the fetus is made to exclude gross abnormalities (Figs 6.1–6.3).

Fig. 6.2 The scan shows an empty amniotic sac at 11 weeks’ gestation. The patient aborted 1 week later.

Down syndrome and trisomy 18

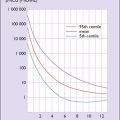

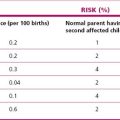

Although the risk of Down syndrome and other trisomies, such as trisomy 18, is age related (Table 6.3), because the majority of babies are born to mothers under 35 most centres now offer screening to all women. Three screening regimens are commonly employed. The first calculates the risk using pregnancy-associated plasma protein A and free β-hCG levels at 9–13 weeks’ gestation, with the aim to take the serum sample at 10 weeks’. The second measures the nuchal thickness of the fetus between 11 weeks 0 days and 13 weeks 6 days: in about 80% of fetuses with Down syndrome there is increased fluid accumulation behind the neck (see Figs 6.4 and 6.5). The risk is then calculated using the nuchal thickness measurement combined with maternal age. The third method combines the levels of β-hCG, α-fetoprotein (AFP) and free unconjugated oestriol measured between 15 and 20 weeks. Oestriol and AFP levels are lower in fetuses with Down syndrome and β-hCG levels are raised. In some centres inhibin A levels are also used, as this increases the detection rate from 65% to 75–80%.

Table 6.3 The incidence of Down syndrome (T21) and trisomy 18 (T18) according to maternal age and gestational age. Note the fall between early pregnancy and birth, which is due to spontaneous pregnancy loss and to selective termination of pregnancy.

Medical imaging in pregnancy

The role of ultrasound examination in obstetrics is shown in Box 6.2. Examples of ultrasound imaging are shown in Figures 6.4–6.11.

Box 6.2 Some indications for ultrasound imaging in pregnancy

| Weeks | |

|---|---|

| 0–10 |

Do not use ultrasound to diagnose pregnancy, but scan if there is any doubt about gestational age, particularly if chorionic villus sampling is considered

|

Fig. 6.9 Scan at 18 weeks’ gestation showing the failure of fusion of the spine in a fetus with spina bifida.

Fig. 6.11 Scan showing a fetus with three toes on the left foot; the right foot is developing normally.

CARE OF THE PREGNANT WOMAN

With this background information it is now possible to discuss the care of a pregnant woman. As mentioned in Chapter 1, most women have a good idea that they are pregnant when they visit a medical practitioner to confirm the diagnosis. At this visit the doctor will inquire about the present pregnancy, the history of previous pregnancies, family history, previous illnesses or infections (including genital herpes, varicella and HIV/AIDS) and other matters and will examine the woman as already described.

Blood pressure

A significant rise in blood pressure from the baseline in early pregnancy provides an early warning that the patient may develop gestational hypertension or the more severe pre-eclampsia (see Ch. 14). For this reason the woman’s blood pressure should be measured at each antenatal visit.

Laboratory tests

Several laboratory tests are made at the first antenatal visit, either by the health professional consulted or, if the woman is referred to a hospital antenatal clinic or to an obstetrician as a private patient, at the referral visit (Box 6.3).

Box 6.3 Routine laboratory tests at the first or early antenatal consultation

At first antenatal visit

| Blood: |

FREQUENCY OF ANTENATAL VISITS

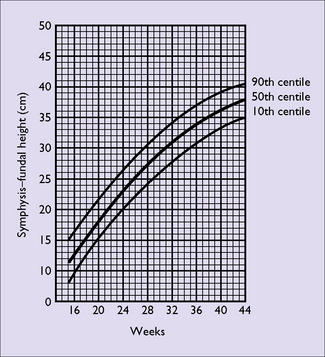

Whatever schedule is adopted, a pregnant woman should be asked at each antenatal visit if she has any problems she wishes to discuss and if she is feeling fetal movements. She should have her blood pressure measured, her urine tested for protein where indicated, and the height of her fundus estimated (see Fig. 1.7, p. 7) or measured with a tape measure (Fig. 6.12) to evaluate the growth of the fetus. Once the fundus of the uterus can be palpated abdominally the fetal heart can be detected with a hand-held Doppler and women find it reassuring to hear the fetal heart at each visit. If an abnormal heart rhythm or rate is heard a formal ultrasound assessment of the fetal heart should be performed.

PREPARATION FOR BREASTFEEDING

GROWTH OF THE FETUS DURING PREGNANCY

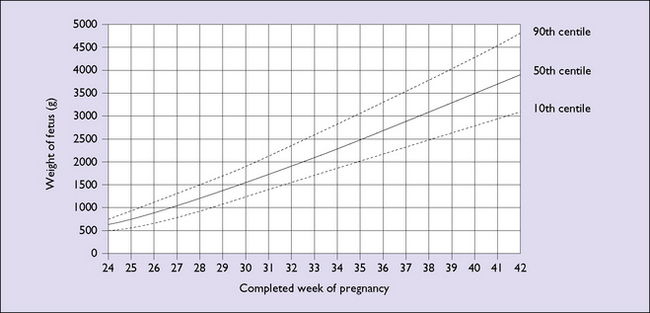

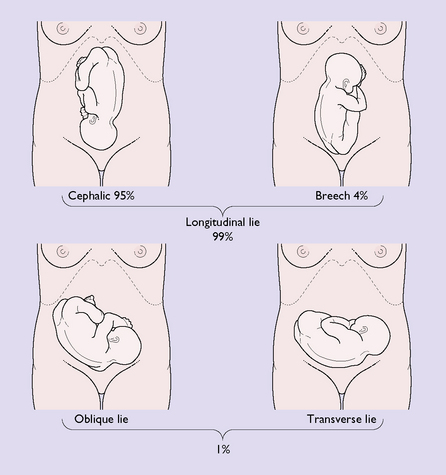

As mentioned above, fetal growth can be determined roughly by the height of the fundus or the distance between the symphysis pubis to the top of the uterus. A more accurate assessment of the fetal growth and weight can be obtained by ultrasound imaging (Fig. 6.13), but this is only required in some pregnancies, for example if the doctor suspects that the fetus is either growth restricted or macrosomic or when medical complications associated with abnormal growth are present. Until about the 28th week of pregnancy the position of the fetal head (or buttocks) relative to the mother’s pelvis is of little clinical importance. After that time it becomes increasingly important, and should be monitored by the doctor or midwife. For the purposes of communication descriptive terms are used:

Technique of abdominal examination

The patient assumes a reclining position, having emptied her bladder. The abdominal examination to the fetus is made by four ‘manoeuvres’, which are shown in Figures 6.15–6.18. The information is recorded in the patient’s antenatal records.

ANTENATAL INFORMATION

Certain matters affecting the mother during pregnancy should be discussed at the early visits.

Smoking

Smoking is a major contributor to perinatal morbidity and mortality (see Table 6.4). One-third of sudden infant deaths (SID) are attributable to cigarette smoking.

| RELATIVE RISK (RR) | |

|---|---|

| Preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) | 2.0–5.0 |

| Premature delivery | 1.2–2.0 |

| Placental abruption | 1.4–2.4 |

| Placenta praevia | 1.5–3.0 |

| Intrauterine growth restriction | 1.5–10.0 |

| Perinatal mortality | 1.3 |

Encouraging and supporting smokers to quit smoking is the single most effective way to reduce premature birth. The ‘5 As’ approach is recommended as the minimum approach to aid the woman to quit and stay quit – see Box 6.4.

Recreational drugs

Alcohol

Cocaine

Heavy use of cocaine (coke, crack) is associated with:

As with alcohol these complications are compounded by the abuse of other drugs and poor lifestyle.