Anorectum

ANATOMY

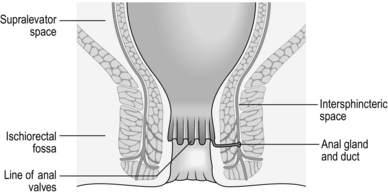

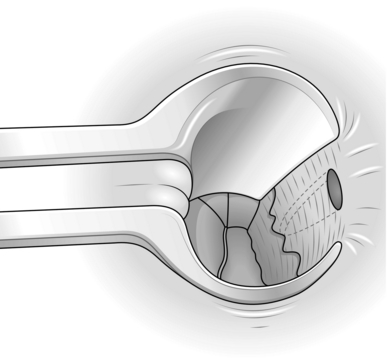

The anal canal extends from the anorectal junction to the anal margin and is approximately 3–4 cm long in men and 2–3 cm long in women. The lining epithelium is characterized by the anal valves midway along the anal canal. This line of the anal valves is often referred to as the ‘dentate line’ (Fig. 14.1): it does not represent the point of fusion between the embryonic hindgut and the proctoderm, which occurs at a higher level, between the anal valves and the anorectal junction. In this zone, sometimes called the transitional zone, there is a mixture of columnar and squamous epithelium.

Spaces

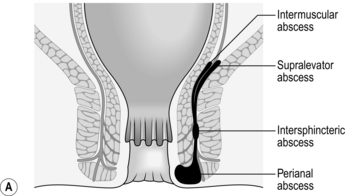

There are three important spaces around the anal canal: the intersphincteric space, the ischiorectal fossa and the supralevator space (Fig. 14.1). These spaces are important in the spread of sepsis and in certain operations:

The intersphincteric space lies between the two sphincters and contains the terminal fibres of the longitudinal muscle of the large intestine. It also contains the anal intermuscular glands, approximately 12 in number, arranged around the anal canal. The ducts of these glands pass through the internal sphincter and open into the anal crypts.

The intersphincteric space lies between the two sphincters and contains the terminal fibres of the longitudinal muscle of the large intestine. It also contains the anal intermuscular glands, approximately 12 in number, arranged around the anal canal. The ducts of these glands pass through the internal sphincter and open into the anal crypts.

The ischiorectal fossa lies lateral to the external sphincter and contains fat. Abscesses may occur in this site as the result of horizontal spread of infection across the external sphincter.

The ischiorectal fossa lies lateral to the external sphincter and contains fat. Abscesses may occur in this site as the result of horizontal spread of infection across the external sphincter.

The supralevator space lies between the levator ani and the rectum. It is also important in the spread of infection.

The supralevator space lies between the levator ani and the rectum. It is also important in the spread of infection.

Prepare

1. Familiarize yourself with the small range of essential instruments for examination of the patient, such as the proctoscope and the rigid sigmoidoscope. In awake patients with anal sphincter spasm, use a small paediatric sigmoidoscope.

2. Operating proctoscopes of the Eisenhammer, Parks and Sims type are essential for operations on and within the anal canal.

3. Use a pair of fine scissors, fine forceps (toothed and non-toothed), a light needle-holder, Emett’s forceps and a small no. 15 scalpel blade for intra-anal work. Alternatively, diathermy dissection creates a virtually bloodless field.

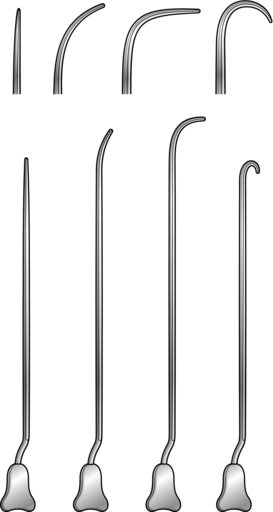

4. For fistula surgery have a set of Lockhart-Mummery fistula probes (Fig. 14.3), together with a set of Anel’s lacrimal probes.

5. Most patients require no preparation, or two glycerine suppositories, to ensure that the rectum is empty before anal surgery. If for any reason the bowels need to be confined postoperatively, carry out a full bowel preparation to empty the whole large intestine.

6. Minor operations can be performed under local infiltration anaesthesia; larger procedures demand regional or general anaesthesia.

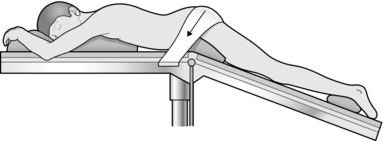

7. For outpatient procedures use the left lateral position, or alternatively the knee-elbow position. For anal operations most British surgeons favour the lithotomy position, although the prone jack-knife position (Fig. 14.4) can also be used.

Fig. 14.4 The jack-knife position.

8. If you prefer to shave the area before starting an anal operation, carry it out in the operating theatre immediately beforehand, where there is good illumination.

HAEMORRHOIDS

Appraise

1. Haemorrhoids usually do not need treatment if the symptoms are minimal and you have excluded a primary cause.

2. Small internal haemorrhoids can be treated by injection sclerotherapy. Prolapsing haemorrhoids may be ligated with rubber-bands. Large prolapsing haemorrhoids, which are usually accompanied by a significant external component, are best treated by haemorrhoidectomy. The advent of day-case diathermy haemorrhoidectomy has rendered surgical treatment simpler and more available than in the past.

3. As a rule avoid treating haemorrhoids if the patient also has Crohn’s disease.

INJECTION SCLEROTHERAPY

Action

1. Pass the full-length proctoscope and withdraw it slowly to identify the anorectal junction – the area where the anal canal begins to close around the instrument.

2. Place a ball of cotton wool into the lower rectum with Emett’s forceps to keep the walls apart. Since you will not usually remove it, warn the patient that it will pass out with the next motion.

3. Identify the position of the right anterior, left lateral and right posterior haemorrhoids.

4. Fill a 10-ml Gabriel pattern syringe with 5% phenol in arachis oil with 0.5% menthol (oily phenol BP).

5. Through the full-length proctoscope, insert the needle into the submucosa at the anorectal junction at the identified positions of the haemorrhoids in turn. Inject 3–5 ml of 5%phenol in arachis oil into the submucosa at each site, to produce a swelling with a pearly appearance of the mucosa in which the vessels are clearly seen. Move the needle slightly during injection to avoid giving an intravascular injection.

6. Delay removing the needle for a few seconds following the injection, to lessen the escape of the solution. If necessary, press on the injection site with cotton wool to minimize leakage.

7. Warn the patient to avoid attempts at defecation for 24 hours.

RUBBER-BAND LIGATION

1. This can also be performed as an outpatient procedure and does not require anaesthesia.

2. There are several different designs of band applicator (Fig. 14.5); the suction bander is relatively expensive, but is convenient and easy to use.

3. There are two conceptually different strategies:

Band, or inject, above the haemorrhoid in order to ‘hitch’ it back into its normal place. Grasp the redundant mucosa proximal to the haemorrhoid and band that.

Band, or inject, above the haemorrhoid in order to ‘hitch’ it back into its normal place. Grasp the redundant mucosa proximal to the haemorrhoid and band that.

4. Enquire about anticoagulants pre-procedure. Banding should not be performed if the patient is on Warfarin or Clopidigrel and some surgeons prefer to stop Aspirin as well.

NOTE: the bands are usually marked as being latex-free.

Action

1. Load one band onto the end of the sucker and one onto the applicator before applying your gloves.

2. Pass the full-length proctoscope and withdraw it slowly to identify the anorectal junction. Position the end of the proctoscope midway between the anorectal junction and the dentate line.

3. The haemorrhoids will fall into view and then the end of the suction device can be applied. Cover the hole on the device to activate the suction and then wait for a few seconds.

4. The band can then be deployed.

5. Any number of haemorrhoids can be banded on each occasion; however, the view is often obscured once two bands have been applied. Repeat banding where necessary but delay it for 6–8 weeks.

Aftercare

1. Advise the patient to take a mild analgesic and sit in a hot bath if the procedure causes discomfort.

2. Pain developing slowly in 1–2 days may be from ischaemia. Analgesics relieve the pain. Give metronidazole tablets 200–400 mg three times daily, which may help reduce inflammation.

3. Advise the patient that the haemorrhoid and the band should drop off after 5–10 days and may be accompanied by a small amount of bleeding.

4. Warn the patient that secondary haemorrhage occurs in approximately 2% any time up to 3 weeks after the application. Tell the patient to report to hospital if this is severe, since it may require transfusion and operative control of the bleeding.

HAEMORRHOIDECTOMY

Prepare

1. Start lactulose, a non-absorbed disaccharide which produces an osmotic bowel action, 30 ml twice daily 2 days preoperatively. This reduces postoperative pain.

2. Give oral metronidazole 400 mg t.d.s. for 5 days, which also significantly reduces postoperative pain.

3. Place the anaesthetized patient in the lithotomy position with some head-down tilt. Avoid caudal anaesthetic as it may provoke retention of urine.

Assess

1. Plan the operation by inserting the Eisenhammer retractor and establish which haemorrhoids need to be removed; also estimate the state and size of the skin bridges (Fig. 14.6).

A three-quadrant haemorrhoidectomy will be sufficient

A three-quadrant haemorrhoidectomy will be sufficient

There is one additional haemorrhoid that needs removal, or the situation is more complex than this.

There is one additional haemorrhoid that needs removal, or the situation is more complex than this.

3. If there is one additional haemorrhoid you may:

Leave it and be prepared to return on another occasion if it proves troublesome

Leave it and be prepared to return on another occasion if it proves troublesome

Fillet it out by undermining the skin bridge

Fillet it out by undermining the skin bridge

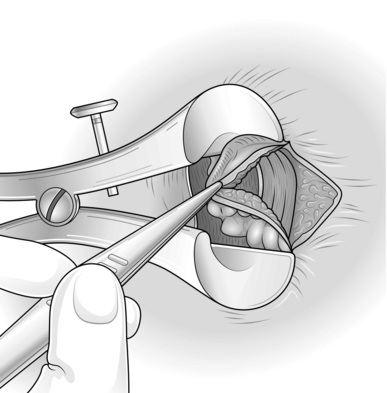

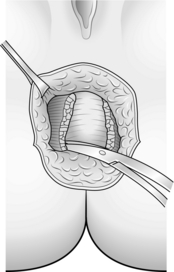

Another technique is to divide the skin bridge above the dentate line, reflect it out of the anus, and trim the haemorrhoid with the back of a pair of scissors. Now excise any redundant mucosa and stitch the trimmed flap back into position with 2/0 synthetic absorbable sutures of Vicryl (Fig. 14.7).

Another technique is to divide the skin bridge above the dentate line, reflect it out of the anus, and trim the haemorrhoid with the back of a pair of scissors. Now excise any redundant mucosa and stitch the trimmed flap back into position with 2/0 synthetic absorbable sutures of Vicryl (Fig. 14.7).

4. The haemorrhoids may be even more extensive and may be circumferential. In this case:

Perform a standard three-quadrant haemorrhoidectomy and return on another occasion to deal with any residual haemorrhoids

Perform a standard three-quadrant haemorrhoidectomy and return on another occasion to deal with any residual haemorrhoids

If you are experienced in the technique, consider performing the circumferential Whitehead haemorrhoidectomy described in 1882 by the English surgeon Walter Whitehead (1840–1914). He described the excision of a tubular segment of the anal canal, with mucosal-cutaneous re-anastomosis. Use polyglactin 910 (Vicryl). Difficulties include the Whitehead deformity – mucosal ectropion (Greek: ek = out + trepein = to turn) – and late stenosis.

If you are experienced in the technique, consider performing the circumferential Whitehead haemorrhoidectomy described in 1882 by the English surgeon Walter Whitehead (1840–1914). He described the excision of a tubular segment of the anal canal, with mucosal-cutaneous re-anastomosis. Use polyglactin 910 (Vicryl). Difficulties include the Whitehead deformity – mucosal ectropion (Greek: ek = out + trepein = to turn) – and late stenosis.

Action

1. Inject bupivacaine (Marcaine) 0.25% with adrenaline (epinephrine) 1:200 000 into each skin bridge and into the external component of each haemorrhoid to be excised.

2. Wait, and gently massage away excess fluid from the injection with a moistened gauze.

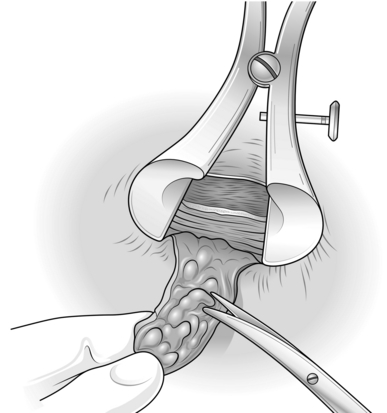

3. Commence with the left lateral haemorrhoid. Place the Eisenhammer retractor in the anal canal and open it sufficiently to put the internal sphincter under tension. This demonstrates the plane of the dissection (Fig. 14.8).

4. Grasp the external component and excise it with electrocautery, using cutting diathermy on skin and coagulating diathermy for all other dissection (Fig. 14.9).

5. Now extend the haemorrhoidal dissection up the anal canal, separating the haemorrhoid from the underlying internal sphincter.

6. Narrow the pedicle as you dissect up towards the apex, otherwise you risk encroaching on the skin bridge.

7. When you have encompassed the internal component of the haemorrhoid, simply transect the pedicle with diathermy.

8. Repeat the procedure on the right anterior haemorrhoid and then the right posterior haemorrhoid.

9. Ensure complete haemostasis and check each wound and apex.

Aftercare

1. Allow the patient home after recovery from the anaesthetic.

2. Warn that there is likely to be an early increase in pain 3–5 days postoperatively.

3. Pain can usually be satisfactorily controlled with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

4. Manage the bowels with lactulose 30 ml orally twice daily until defecation is comfortable.

5. Some surgeons advocate a reversible chemical sphincterotomy with locally applied 0.2% glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) applied three times daily.

6. Review the patient in the outpatient clinic within 10–12 days.

FISSURE

Appraise

1. Most ulcers at the anal margin are simple fissures in ano, possibly associated with a sentinel skin tag and/or hypertrophied anal papilla or anal polyp.

2. Exclude excoriation in association with pruritus ani, Crohn’s disease, primary chancre of syphilis, herpes simplex, leukaemia and tumours.

3. Treat superficial fissures with 2% diltiazem ointment (Anoheal™) or 0.4% glyceryl trinitrate cream (Rectogesic™) twice a day. GTN can cause headaches; diltiazem occasionally causes local irritation.

4. Botulinum toxin injection is an alternative therapy, especially useful in patients who are non-compliant in regularly applying creams. Doses of botulinum toxin type A (Botox) may range from 2.5 to 50 units and reports have included injections into the internal and external anal sphincter either directly into the fissure or at sites removed from it. Dysport is an alternative preparation which requires roughly three times the number of units used with Botox. However, studies suggest that the two formulations are not bioequivalent, whatever the dose relationship.

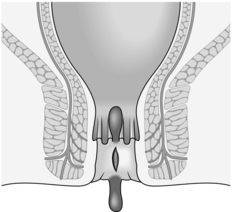

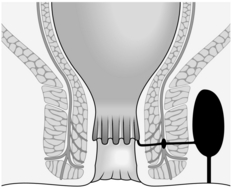

5. Reserve operation for failures, which are more common when there is a sentinel tag, an anal polyp, exposure of the internal sphincter or undermining of the edges (Fig. 14.11).

Fig. 14.11 A fissure with a sentinel skin tag, an anal polyp and undermining of the edges of the ulcer.

6. Anal dilatation is no longer an acceptable treatment as it causes unpredictable stretching of the internal and external sphincters and lower rectum, producing an unacceptable risk of incontinence.

7. The standard procedure is a lateral (partial internal) sphincterotomy.

LATERAL SPHINCTEROTOMY

Appraise

1. This is very successful, curing more than 95% of patients. It was introduced by Eisenhammer in 1951.

2. To avoid exacerbating the pain, avoid preoperative preparation.

3. The operation can be carried out as a ‘day-case’ procedure.

4. Warn the patient of a 1 in 20 chance of permanent flatus incontinence and a 1 in 200 chance of faecal leakage.

Action

1. Place the patient in the lithotomy position, with general or regional anaesthesia.

2. Pass an Eisenhammer bivalve operating proctoscope. Examine the fissure to exclude induration suggestive of an underlying intersphincteric abscess.

3. Remove hypertrophied anal papillae or a fibrous anal polyp, sending them for histopathological examination. Remove a sentinel skin tag.

4. Rotate the operating proctoscope to demonstrate the left lateral aspect of the anal canal. Palpate the lower border of the internal sphincter muscle. If desired, you may replace the Eisenhammer retractor with a Parks’ retractor which permits outward traction, making the internal sphincter more obvious.

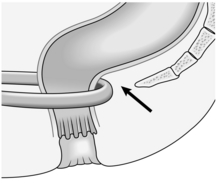

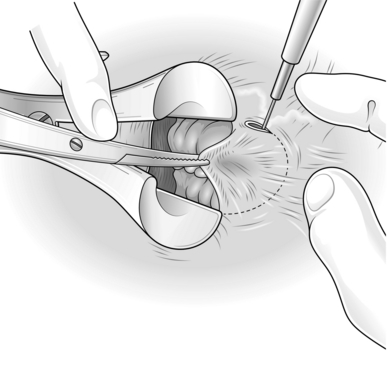

5. Make a small incision 1 cm long in line with the lower border of the internal sphincter. Insert scissors into the submucosa, gently separating the epithelial lining of the anal canal from the internal sphincter, and also into the intersphincteric space to separate the internal and external sphincters.

6. If you make a hole in the mucosa open it completely to avoid the risk of sepsis.

7. Clamp the isolated area of the internal sphincter with artery forceps for 30 seconds. This markedly reduces haemorrhage.

8. With one blade of the scissors on each side of it, divide the internal sphincter muscle up to the level of the top of the fissure (Fig. 14.12).

Fig. 14.12 Lateral partial internal sphincterotomy.

ANAL ABSCESS AND FISTULA

Appraise

1. Most abscesses and fistulas in the anal region arise from a primary infection in the anal intersphincteric glands. Furthermore, they represent different phases of the same disease process. An acute-phase abscess develops when free drainage of pus is prevented by closure of either the internal or external opening of the fistula (or both).

2. Other causes of sepsis in the perianal region include pilonidal infection, hidradenitis suppurativa, Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis and intrapelvic sepsis draining downwards across the levator ani.

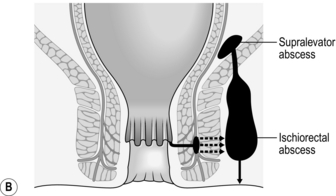

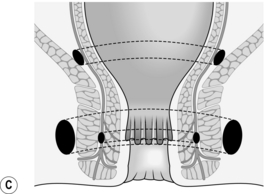

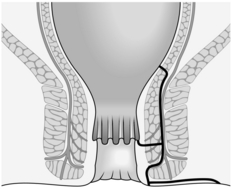

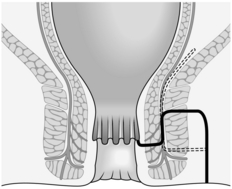

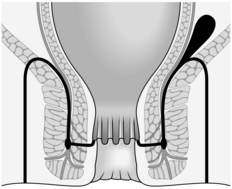

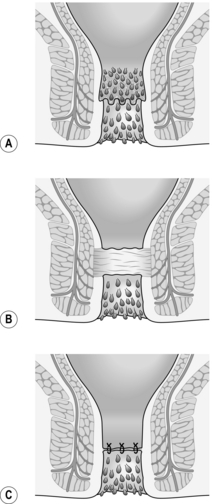

3. Once established, an intersphincteric abscess may spread vertically downwards to form a perianal abscess or upwards to form either an intermuscular abscess or supralevator abscess, depending upon which side of the longitudinal muscle spread occurs (Fig. 14.13A). Horizontal spread medially across the internal sphincter may result in drainage into the anal canal, but spread laterally across the external sphincter may produce an ischiorectal abscess (Fig. 14.13B). Finally, circumferential spread of infection may occur from one intersphincteric space to the other, from one ischiorectal fossa to the other and from one supralevator space to the other (Fig. 14.13C).

4. Once an abscess has formed surgical drainage must be instituted; antibiotics have no part to play in the primary management. As the tissues are inflamed and oedematous, do the minimum to promote resolution of the infection. More tissue can be divided later to resolve the condition. Send a specimen of pus to the laboratory for culture. The presence of intestinal organisms suggests the presence of a fistula.

5. Avoid preoperative preparation of the bowel as it causes unnecessary pain.

6. Place the anaesthetized patient in the lithotomy position and shave the operation area.

PERIANAL ABSCESS

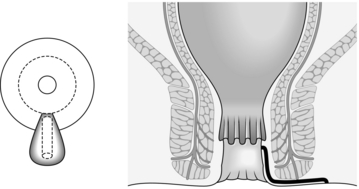

1. Recognize the abscess as a swelling at the anal margin.

2. Make a radial incision and excise overhanging edges. Allow pus to drain and send a sample to the laboratory.

3. Gently examine the wound to see if there is a fistula.

4. Insert a gauze dressing soaked in normal saline solution and surrounded by Surgicel. Do not pack the wound tightly.

INTERMUSCULAR ABSCESS

1. Recognize the abscess as an indurated swelling, sometimes mobile within the lower rectal wall.

2. As this is an upward extension of an intersphincteric abscess, manage it similarly, but the upper limit of division of the internal sphincter and/or circular muscle of the rectum is higher.

3. Control bleeding from the divided edges of the rectal wall.

4. Insert a gauze dressing soaked in normal saline to the upper limit of the wound. Do not pack the wound tightly.

SUPRALEVATOR ABSCESS

1. This is recognizable as a fixed indurated swelling palpable above the anorectal junction.

2. Drainage of a supralevator abscess extends upwards to a similar level as an intermuscular abscess, except that the whole rectal wall needs to be divided.

3. Insert a gauze dressing soaked in normal saline, surrounded by Surgicel, into the anal canal to the upper limit of the wound. Do not pack the wound tightly.

ISCHIORECTAL ABSCESS

1. Recognize this as a brawny inflamed swelling in the ischiorectal fossa.

2. An ischiorectal abscess often spreads circumferentially from one side to the other, so carefully examine the patient under anaesthesia to determine if this has occurred. Recognize the abscess by feeling the induration inferior to the levator ani muscle.

3. For the same reason, employ a circumanal incision to establish drainage. Excise the skin edges to create an adequate opening and send a specimen of pus to the laboratory.

4. Gently insert a gauze dressing soaked in normal saline surrounded by Surgicel to the upper limit of the wound. Do not pack the wound tightly.

Postoperative

1. Remove the dressing on the second postoperative day while the patient lies in the bath, having been given an intramuscular injection of pethidine 100 mg or papaveretum 7–15 mg.

2. Initiate a routine of twice-daily baths, irrigation of the wound and the insertion of a tuck-in gauze dressing soaked in physiological saline or 1:40 sodium hypochlorite solution.

3. If the patient has evidence of persistent local or systemic sepsis, administer systemic antibiotics guided by the culture report. Metronidazole is effective against anaerobic organisms.

4. Assess the patient for the possible presence of a fistula detected at the time of abscess drainage, or a history of recurrent abscesses, or palpable induration of the perianal area, anal canal and lower rectum, or the presence of gut organism in the pus. If so, plan to re-examine the patient under anaesthesia and carry out the appropriate treatment.

FISTULA

Appraise

1. A fistula is an abnormal communication between two epithelial-lined surfaces. Therefore, in the context of fistula in ano, there should be an external opening on the perianal skin, an internal opening into the anal canal and a track between the two.

2. There may be no external opening, or it may be healed over. Likewise, there may be no internal opening as the sepsis arises in the area of the intersphincteric gland, which is the primary site of infection. It may not drain across the internal sphincter into the anal canal. Finally, the track may follow a very complicated path.

3. The presence of infection is characterized by the physical sign of induration, detected by palpation with a lubricated, covered finger.

SUPERFICIAL FISTULA

Assess

1. Place the anaesthetized patient in the lithotomy position. Always perform sigmoidoscopy, looking especially for inflammatory bowel disease.

2. Palpate the perianal skin, anal canal and lower rectum to detect induration. This is confined to the distal anal canal and localized to one area, as superficial fistulas are really fissures covered with skin and lower anal canal epithelium (Fig. 14.14).

Action

1. Insert a bivalve operating proctoscope and pass a fine probe along the track.

2. Lay open the fistula using a no. 15 bladed knife or electrocautery.

3. Curette the granulation tissue and send a specimen for histopathology.

4. If there is no induration deep to the internal sphincter, fashion the external skin wound so that it becomes pear-shaped and perform a lateral sphincterotomy (see above).

5. Insert a gauze dressing soaked in normal saline solution and surrounded by Surgicel to the upper limit of the wound.

INTERSPHINCTERIC FISTULA

1. An intersphincteric fistula results when the sepsis is inside the striated muscle of the pelvic floor and the anal canal (Fig. 14.15).

Assess

1. Have the anaesthetized patient in the lithotomy position. Perform sigmoidoscopy in all cases, especially looking for inflammatory bowel disease.

2. Palpate carefully for induration. There is often a long subcutaneous perianal track leading to the external opening. You can feel induration in the wall of the anal canal between a finger in the anal canal and the thumb externally. If there is an upward extension, you feel induration in the rectal wall. Although the internal opening into the rectum may be above the anorectal ring, laying it open is not difficult, as the striated muscle will not be divided. Remember that there may not be an internal opening.

Action

1. Insert a bivalve operating proctoscope and pass a fistula probe, such as Lockhart-Mummery’s, or Anel’s lacrimal probe, along the track. This runs parallel to the long axis of the anal canal.

2. If there is a long subcutaneous track, the probe is directed from the external opening towards the anus. Lay it open and remove the granulation tissue with a curette. The upward extension between the sphincters becomes apparent as granulation tissue exudes from the opening.

3. Divide the internal sphincter as high as the tip of the probe. Again remove granulation tissue by curettage. If no granulation tissue protrudes from a residual part of the track, and palpation reveals no more induration, do nothing more.

4. If necessary, totally divide the internal sphincter and the muscle of the lower rectum completely, to lay open the fistula.

5. Create an adequate external wound to allow drainage.

6. Insert a gauze dressing soaked in normal saline solution surrounded by Surgicel. Do not pack the wound tightly.

TRANS-SPHINCTERIC FISTULA

1. In a trans-sphincteric fistula, the primary track passes across the external sphincter from the intersphincteric space to the ischiorectal fossa. The infection may also have drained across the internal sphincter into the anal canal, where you find the internal opening of the fistula, which is usually at the level of the anal valves (Fig. 14.16).

Fig. 14.16 Trans-sphincteric fistula.

Assess

1. Have the anaesthetized patient in the lithotomy position with the buttocks well down over the end of the table. Invariably perform sigmoidoscopy, especially looking for inflammatory bowel disease.

2. Palpate carefully for induration. The external opening(s) are usually laterally placed and indurated, but there is not usually any induration extending towards the anus subcutaneously in a trans-sphincteric fistula. You may palpate induration within the wall of the anal canal, the site of the primary anal gland infection. Induration is also detected under the levator ani muscles and is often circumferential. Palpate between a finger in the lower rectum, and thumb on the perianal skin, for a large area of induration. This is especially obvious if circumferential spread has not occurred and the contralateral side is normal.

Action

1. Pass a bivalve operating proctoscope in order to try and identify the internal opening.

2. Pass a Lockhart-Mummery probe into the external opening. It may extend several centimetres and can be felt very close to a finger in the rectum. Do not force the probe, and do not pass it into the rectum, as this is never the site of the internal opening.

3. If there is spread of infection towards the midline posteriorly, direct the probe previously inserted into the external opening, posteriorly towards the coccyx. With a scalpel (no. 10 blade) in the groove of the probe divide the tissue between the skin and the probe; divide skin and fat only, you should not divide any muscle. Apply tissue-holding forceps to the skin edges and secure any major bleeding points. Alternatively, perform the laying open with electrocautery.

4. Curette away granulation tissue, sending some for histopathological examination, and look for a forward extension from the site of the external opening. Lay it open.

5. Seek any extension of the sepsis to the opposite side by palpation, probing and looking for granulation tissue pouting from an opening in the previously curetted track. Use a no. 10 bladed knife or electrocautery to divide skin and fat to lay open any further tracks.

6. Insert the bivalve proctoscope again and re-identify the internal opening. It may or may not be possible to pass a probe either through the internal opening into the previously opened tracks or from the previously opened tracks into the anal canal.

7. Divide the anal canal epithelium and the internal sphincter to the level of the internal opening, if present, with a no. 15 bladed knife or electrocautery, thus opening up the intersphincteric space. If there is no internal opening, open the intersphincteric space in a similar way, to the level of the anal valves. Curette any granulation tissue.

8. Now identify the primary track across the external sphincter. If it is at or below the line of the anal valves, divide the muscle. If it is higher, as it often is, it may be possible to divide the muscle, but determining this requires considerable experience. It is often safer to drain the track by inserting a seton: use a length of fine silicone tubing (1 mm diameter) or no. 1 braided suture material. Monofilaments such as nylon are often uncomfortable for the patient because of the sharp ends beyond the knot.

SUPRASPHINCTERIC FISTULA

In a suprasphincteric fistula, the primary track crosses the striated muscle above all the muscles of continence (Fig. 14.18). As this is a variant of a ‘high’ trans-sphincteric fistula, manage it on similar principles.

In a suprasphincteric fistula, the primary track crosses the striated muscle above all the muscles of continence (Fig. 14.18). As this is a variant of a ‘high’ trans-sphincteric fistula, manage it on similar principles.

This is a very rare form of fistula. When possible refer the patient to a surgeon specializing in this field.

This is a very rare form of fistula. When possible refer the patient to a surgeon specializing in this field.

EXTRASPHINCTERIC FISTULA

1. An extrasphincteric fistula arising from an upward extension of infection from the ischiorectal fossa is also unusual and may result from the injudicious use of a probe during operation.

2. Create a defunctioning loop colostomy as a preliminary to closing the opening in the rectum and treat the fistula along the lines indicated above.

3. Manage a fistula arising from pelvic sepsis (for example from acute appendicitis, Crohn’s disease or diverticular disease and not, therefore, of anal gland origin) by treating the primary disease (see Chapters 11, 13).

Postoperative

1. Remove the dressing on the second or third postoperative day after giving an intramuscular injection of pethidine 100 mg or papaveretum 7–15 mg. Carry out the first dressing in the operating theatre under general anaesthesia if the wound is very extensive.

2. Initiate a routine of twice-daily baths, irrigation of the wound and insertion of gauze soaked in physiological saline.

3. Inspect the wound at regular intervals until healing is complete.

4. Encourage the bowel movements to coincide with these dressing times by giving laxatives. If they do not coincide, arrange bath-irrigation-dressing routines as necessary.

5. If there is voluminous discharge of pus, review the wound in the operating theatre under general anaesthesia after 10–14 days. In patients with large wounds, this may need to be repeated. Lay open any residual tracks and curette away the granulation tissue.

6. Administer antimicrobial agents such as ciprofloxacin or metronidazole for up to 28 days, to assist in the elimination of the sepsis. A pus swab may further guide the choice of antibiotic.

7. A seton does not complicate the postoperative routine. Allow the wound to heal around it; this may take 3 months. Then, under general anaesthesia, remove the seton and curette its track free of granulation tissue. Spontaneous healing occurs in approximately 40% of patients. If healing does not occur, lay open the residual track. The advantage of this staged division of the external sphincter is that healing occurs around the ‘scaffolding’ of the external sphincter. When it is subsequently divided – and this is not always necessary – its ends separate only slightly. This produces a better functional result than if it were divided at the outset.

Complications

1. Failure to heal may result from inadequate drainage of the intersphincteric abscess, of secondary tracks, or of the primary track. Give the nurses clear instructions and advice about the dressings. Inadequate postoperative dressings allow bridging of the wound edges and pocketing of pus. If there is excessive growth of granulation tissue, cauterize it with silver nitrate or curette it away under general anaesthetic.

2. Secondary haemorrhage may occur from any potentially septic, open wound healing by second intention.

3. Anal incontinence of varying degrees may follow division of the sphincter muscles. If the entire sphincter complex has inadvertently been divided, consider repairing it once the sepsis has been eradicated and healing has occurred.

4. Successful fistula surgery depends upon accurate definition of the pathological anatomy, drainage of the intersphincteric abscess of origin, the primary and secondary tracks, and excellent postoperative wound care.

OTHER PROCEDURES

A loose seton can be very acceptable to the patient even in the long term, provided that the seton is discrete and comfortable. The use of rubber sloops tied with several silk knots and left dangling between the buttocks will cause irritation and soreness. A neat 1 Ethibond thread, with only two knots, secured with 3/0 Ethibond to anchor the ‘whiskers’ can be completely comfortable, especially with the knots turned into the track.

A loose seton can be very acceptable to the patient even in the long term, provided that the seton is discrete and comfortable. The use of rubber sloops tied with several silk knots and left dangling between the buttocks will cause irritation and soreness. A neat 1 Ethibond thread, with only two knots, secured with 3/0 Ethibond to anchor the ‘whiskers’ can be completely comfortable, especially with the knots turned into the track.

A tight seton is designed to cut through the fistula track slowly, in the hope of reducing the separation of muscle ends. Apply it firmly but not tightly. Replace it at monthly intervals.

A tight seton is designed to cut through the fistula track slowly, in the hope of reducing the separation of muscle ends. Apply it firmly but not tightly. Replace it at monthly intervals.

Specialist colorectal surgeons may create advancement flaps to avoid sphincter division and employ an intersphincteric approach and core-out fistulectomy. The technique is employed particularly in high trans-sphincteric fistulae, especially when situated anteriorly in women, who have a short anal canal, and is successful in around 50% of cases.

Specialist colorectal surgeons may create advancement flaps to avoid sphincter division and employ an intersphincteric approach and core-out fistulectomy. The technique is employed particularly in high trans-sphincteric fistulae, especially when situated anteriorly in women, who have a short anal canal, and is successful in around 50% of cases.

The use of fibrin glues injected into the track and bioprosthetic plugs sutured to the track is appealing in that there is no sphincter destruction and continence is maintained. However, initial enthusiasm over the short-term external opening healing rates has been tempered by a lack of evidence of healing of the track on MRI scanning and high recurrence rates.

The use of fibrin glues injected into the track and bioprosthetic plugs sutured to the track is appealing in that there is no sphincter destruction and continence is maintained. However, initial enthusiasm over the short-term external opening healing rates has been tempered by a lack of evidence of healing of the track on MRI scanning and high recurrence rates.

PILONIDAL DISEASE

Action

1. Determine the extent of sepsis by palpation for induration and by using probes.

2. Completely excise the skin of the septic area.

3. Curette away the granulation tissue and embedded hairs.

4. Check with a probe in the base of the wound to detect any side tracks, and look for any residual granulation tissue that may be pouting from a side track.

5. Fashion the wound so that there are no overhanging edges.

7. Dress the wound with gauze soaked in physiological saline solution and apply pressure to it.

OTHER PROCEDURES

1. Lay open a simple pilonidal sinus and marsupialize (Latin: marsupium = pouch; create a pouch with an open mouth) the wound. This keeps the wound open until the interior has filled up.

2. In Bascom’s operation each pit is excised with a no. 11 bladed knife. Drain the cavity through a laterally placed incision.

3. Various rotation flaps can be used, all having the objective of avoiding a midline suture line.

HIDRADENITIS SUPPURATIVA

Appraise

1. Hidradenitis (Greek: hidros = sweat + aden = gland + itis = inflammation) suppurativa (Latin: = pus-forming) is a septic process that involves the apocrine (Greek: apo = off + krinein = to separate; the secretion is a breakdown product of the cell) sweat glands. It occurs in the perineum as well as the axillae.

2. Recurrent abscess formation often results from inadequate drainage. There is no communication with the anal canal and the infection is superficial. Occasionally, hidradenitis occurs in association with Crohn’s disease and lithium therapy.

3. Combine surgical treatment of acute abscesses with continuing dermatological input as topical or systemic antimicrobial agents, retinoids, hormonal therapy and immunosuppressive medications may also help to control the disease.

Action

1. Drain the pus from each abscess. They are often multiple and may intercommunicate.

2. Curette away all the granulation tissue.

3. Remove all overhanging skin.

4. Allow the defect to heal by second intention.

5. In very severe cases it may be necessary to excise and graft an area most affected in order to prevent multiple recurrences.

ANAL MANIFESTATIONS OF CROHN’S DISEASE

Appraise

1. These occur in approximately 50% of patients affected with Crohn’s disease.

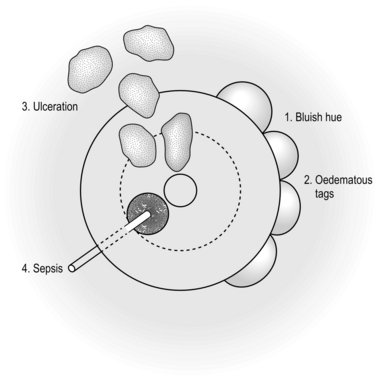

2. The perianal area has a bluish discoloration and there may be oedematous skin tags. Ulceration, which can be extensive, may involve the perianal skin, anal margin and anal canal. Sepsis may occur in the form of either an abscess or a fistula (Fig. 14.19).

Action

1. Remove a small biopsy specimen of a skin tag, or granulation tissue together with a rectal mucosal biopsy for histopathological examination.

2. Drain any abscess in the usual way, taking care not to divide any muscle.

3. For long-term seton drainage of fistulas, again prefer a soft suture material such as No. 1 Ethibond. By using 3/0 Ethibond a secure knot can be tied without the need for too many ‘throws’ that would create a bulky knot. Again turn the knot so that it lies within the track, leaving only a smooth loop of suture on the outside.

CONDYLOMATA ACUMINATA

Appraise

1. Condylomata acuminata (genital warts) result from human papillomavirus (HPV) infection of the squamous epithelium. Papilliferous lesions may develop on the perianal skin, within the anal canal and on the genitalia. Exclude other forms of sexually transmitted disease and attempt to trace contacts.

2. Treat scattered lesions by applying 25% podophyllin in compound benzoin tincture. Treat more extensive lesions by operation using the technique of scissor excision.

Action

1. Have the anaesthetized patient placed in the lithotomy or prone jack-knife positions.

2. Infiltrate a solution of 1:300 000 adrenaline (epinephrine) in normal saline under the epithelium bearing the perianal lesions to reduce bleeding during excision of the warts and to separate the individual lesions, thus preserving the maximum amount of normal skin.

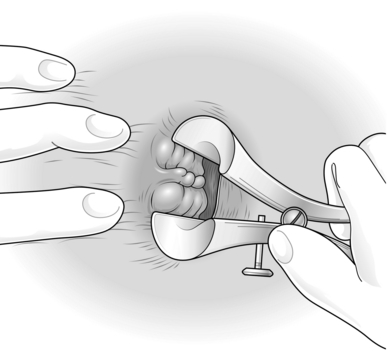

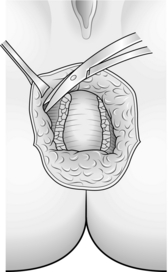

3. Hold the warts with fine-toothed forceps and remove them with pointed scissors.

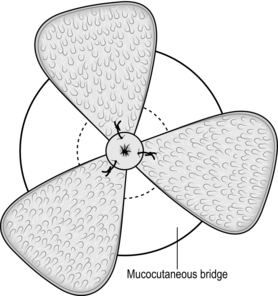

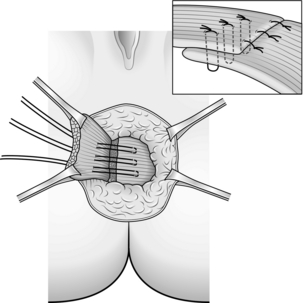

4. Remove intra-anal canal warts in the same way after inserting a bivalve operating proctoscope. There is often a confluent ring of lesions in the upper anal canal. Totally remove these and then join the mucosa of the lower rectum to that of the anal canal at the dentate line with sutures (Fig. 14.20). In addition to achieving mucosal apposition, this mucosal anastomosis is haemostatic.

5. Send the excised lesions, particularly the intra-anal ones, for histopathological examination.

ANAL TUMOURS

ANAL MARGIN TUMOURS

Appraise

1. These may be benign or malignant. Condylomata acuminata, keratoacanthoma, apocrine gland tumours, premalignant Bowen’s disease and Paget’s disease are benign.

2. Excise condylomata acuminata (warts) with scissors as above.

3. Totally excise other tumours. If the defect is not too large allow the wound to heal by second intention. Close large defects with split skin grafts.

4. Histopathological information is essential in deciding whether or not any further treatment is required.

5. Malignant tumours of the anal margin are mainly squamous cell carcinomas, although basal cell carcinoma can occur. Induration suggests malignancy. Small microinvasive carcinomas can be adequately treated by wide local excision, but more advanced cancers require a combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy (see below).

ANAL CANAL TUMOURS

Appraise

1. These are almost always malignant and include squamous cell carcinoma, basaloid carcinoma, adenocarcinoma and malignant melanoma.

2. Examine the tumour under anaesthesia and remove a biopsy specimen.

3. There is virtually no indication for local excision in infiltrative squamous carcinoma of the anal canal, which may be treated conservatively in the majority of cases by primary radiotherapy with chemotherapy. Reserve surgery for residual tumour, complications of therapy or subsequent tumour recurrence.

4. If surgery is indicated after failed combined modality therapy, then this usually requires abdominoperineal excision of the rectum and anal canal (see Chapter 13), widely excising the perianal skin, ischiorectal fossa fat and the levator ani muscles near the lateral pelvic wall. Ensure that you have positive histology after radiochemotherapy of a squamous carcinoma prior to performing an abdominoperineal resection.

RECTAL ADENOMAS

Appraise

1. Adenomas of the rectum may be classified on a histopathological basis into tubular, tubulovillous and villous. From the clinical viewpoint these three types of adenoma are similar in their behaviour as there is no invasion of neoplastic cells across the muscularis mucosae. A more useful classification is according to their clinical appearance; for example, are they pedunculated or sessile?

2. Are there any other neoplastic lesions – benign or malignant – in the large intestine? In patients with lesions more than 2 cm in diameter, there is an incidence of further tumours of 25% (benign 18%, malignant 7%). Order a colonoscopy.

3. Is the lesion totally benign or does it have malignant areas? There is a 50% chance of malignant areas in patients with lesions larger than 2 cm in diameter.

4. Be sure to remove the whole lesion by performing a total excision biopsy, which is diagnostic as well as therapeutic if the lesion proves to be totally benign. Do not perform an incision biopsy as it is not representative of the whole lesion and makes subsequent submucosal excision difficult.

Action

1. Totally remove lesions less than 5 mm across by twisting with a pair of Patterson biopsy forceps.

2. Employ diathermy snare excision for those that are pedunculated.

3. Submucosally excise those that are sessile, non-circumferential and confined to the lower two-thirds of the rectum (see below).

4. Those in the lower third of the rectum that are circumferential may be suitably excised by a modified Soave operation (see below).

5. Employ anterior resection for sessile non-circumferential tumours with the lower border in the upper third of the rectum, and circumferential tumours with the lower border in the upper two-thirds of the rectum.

SUBMUCOSAL EXCISION OF SESSILE ADENOMA

Action

1. Insert a bivalve operating proctoscope and ensure that illumination is adequate. You may find it advisable to wear a headlamp.

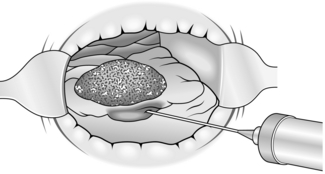

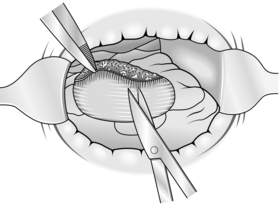

2. Inject 1:300 000 adrenaline (epinephrine) in physiological saline into the submucosa under the tumour.

3. With sharp scissors or electrocautery incise the mucosa approximately 1 cm from the edge of the tumour and then dissect it free of the circular muscle of the rectum, which appears as white fibres in the distended submucosal layer (Fig. 14.22).

4. Seal bleeding points with diathermy.

5. Allow the wound to heal spontaneously without suturing it. Close any defect you inadvertently created in the muscle with sutures.

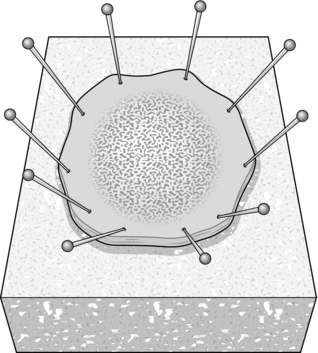

6. Pin the specimen to a cork board before fixing it, so that the pathologist can determine whether or not there is any malignant invasion, by taking serial sections (Fig. 14.23).

Postoperative

1. No special measures need be adopted other than to ensure that constipation does not occur.

2. Haemorrhage is a rare complication.

3. Study the histopathological report. If there are malignant foci, decide whether or not to proceed to a more radical procedure.

4. Follow-up the patient to detect any recurrence and metachronous (sequential but separated by appreciable intervals) lesions.

5. Stenosis of the rectum may develop if excision was performed for too large a lesion.

MODIFIED SOAVE OPERATION

1. Reserve this operation for large circumferential lesions with their lower border in the lower third of the rectum and extending into the upper third.

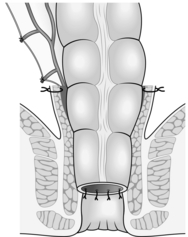

2. In principle the entire tumour is excised submucosally by a combined abdominal and peranal approach. The rectal muscular tube is relined with descending colon, anastomosed through the anus to the level of the dentate line (Fig. 14.24) as described in Chapter 13.

3. Circumferential lesions extending over only a few centimetres can be treated by submucosal excision, with plication of the muscle tube to allow mucosal anastomosis.

4. This is an unusual operation best reserved for performance in a specialist centre.

RECTAL PROLAPSE

Appraise

1. The symptom of prolapse (i.e. tissue slipping through the anus) may result from causes other than complete rectal prolapse. Distinguish haemorrhoids, anal polyps, mucosal prolapse and rectal adenomas. An internally intussuscepted rectum lies in the lower third of the rectum (the first phase of prolapse), whereas a complete prolapse passes through the anal sphincter and keeps it open: sphincter function is inhibited in both cases.

2. Treatment consists of control of the prolapse, re-education of the bowel habit and improvement, if necessary, of sphincter function.

3. First control the prolapse. Many operations have been described to achieve control: in the UK complete rectal prolapse is usually treated either by abdominal rectopexy or by perineal mucosal sleeve resection (Delorme’s procedure, see below).

4. An open abdominal rectopexy is currently rarely performed, but follows the same steps as the laparoscopic operation described below.

5. Abdominal rectopexy is associated with unpredictable postoperative constipation, which in some patients can be severe. There are claims that concomitant sigmoid resection (resection rectopexy, also known as the Frykman-Goldberg operation) reduces this risk.

6. After rectopexy only a few patients have sphincter dysfunction severe enough to produce significant incontinence. Pelvic floor physiotherapy, faradism and electrical stimulators give little long-term benefit. The problem results from pelvic floor neurogenic myopathy producing a shortened anal canal with widening of the anorectal angle. Postanal pelvic floor repair reduces the anorectal angle and lengthens the anal canal, restoring satisfactory continence in some patients.

7. All abdominal pelvic dissection in male patients has the potential to cause either erectile or ejaculatory dysfunction. Because of this it is essential that this complication be mentioned and recorded when obtaining informed consent.

8. The laparoscopic ventral rectopexy is a newer technique which is particularly beneficial in the presence of a rectocele and enterocele as it bolsters the rectovaginal septum. Proponents of the operation suggest it should be the treatment of choice for all patients with rectal prolapse.

LAPAROSCOPIC ABDOMINAL RECTOPEXY

Prepare

1. No bowel preparation is usually required but can be used at the discretion of the clinician.

2. Order metronidazole 500 mg intravenously and Augmentin 1.2 g intravenously at induction of anaesthesia.

3. The patient should be catheterized.

4. Place the anaesthetized patient in the Lloyd-Davies (lithotomy Trendelenburg) position.

Action

1. Make a subumbilical 12-mm incision and enter the peritoneal cavity using the Hasson technique. Place a Hasson trocar in the peritoneal cavity. The camera and stack should be on the patient’s left side. The bed should be tilted to the head down and left lateral position to allow the small bowel to migrate to the upper abdomen. Measures should be taken to avoid the patient slipping off the table.

2. Achieve CO2 pneumoperitoneum to 12–15 mm Hg.

3. Place a 12-mm trocar under direct vision in the right iliac fossa. Insert another 5-mm trocar a hand’s breadth above this trocar. Insert a 3rd 5-mm trocar in the left lateral region.

4. If the small bowel cannot be adequately moved out of the pelvis the ileal attachments to the lateral abdominal wall should be divided to allow the bowel to move cephalad. Starting at the level of the sacral promontory, incise the peritoneum on the medial side beside (but not damaging) the superior haemorrhoidal artery using an energy device such as the harmonic scalpel. Prior to making this incision, use a non-traumatic bowel grasping forceps to retract the rectum superiorly (assistant through the left sided port) and cephalad (surgeons left handed grasper pulling the rectosigmoid cephalad). The incision will result in gas entering the plane of dissection, enabling good visualization of the plane. The ureters lie laterally on both sides, but always check their position. The presacral nerves lie just behind the superior haemorrhoidal artery; take care to preserve them. Extend the dissection in the lateral direction till the left ureter is identified. As the dissection progresses ensure the bow created by the superior haemorrhoidal artery is placed on tension with the left handed grasper. Now extend the peritoneal incision to the bottom of the prerectal pouch, then across the midline between the rectum and vagina or bladder, so that the rectum may be separated from them.

5. Enter the postrectal space and open it up by dissection, holding the rectum forward with your left handed grasper. Exert adequate tension on the rectum to display the areolar tissue. Seal any vessels with the energy device.

6. Now that the anterior and posterior dissection of the rectum is complete its only attachments are the two lateral ligaments. It is arguable whether or not these should be divided.

7. Achieve perfect haemostasis.

8. Using a 3/0 ethibond suture and two needle holders inserted through the right sided port, place a stitch between the upper parts of the lateral ligaments on the right side and the vertebral disc just distal to the sacral promontory; avoiding the median sacral artery. These will suspend the rectum while scarring fixes it in place. Two to three such sutures will ensure the rectum stays attached to the promontory. If the surgeon is not skilled in intracorporeal knot tying, a knot pusher can be used after suture placement.

9. Observe whether the sigmoid loop is redundant. If it is, and particularly if there is a background history of constipation, perform sigmoid resection with end-to-end anastomosis. Otherwise it is not worth resecting the sigmoid colon (Fig. 14.25). To remove the specimen and create the purse-string suture for anvil placement a 3–4-cm left iliac fossa incision can be made.

10. A drain is not usually necessary, but if there is a persistent collection of blood and fluid in the pelvis insert a tube drain for 24 hours.

Postoperative

1. The patient can be commenced on an enhanced recovery programme. If no resection is performed start a normal diet as soon as the patient is able to tolerate it. If a resection is performed, start with free fluids till the patient passes flatus.

2. Remove the catheter on the first postoperative day.

3. Avoid constipation. Give a mild osmotic laxative to initiate bowel movement. Subsequently use suppositories such as glycerine and bisacodyl.

MUCOSAL SLEEVE RESECTION (DELORME PROCEDURE)

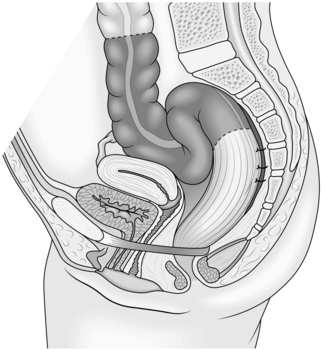

The functional results of this procedure (Fig. 14.26) are good and it is particularly useful if the prolapse is small or incomplete and in high-risk patients who are unsuitable for abdominal surgery.

Action

1. Reproduce the prolapse and infiltrate the submucosal plane with saline containing 1:300 000 adrenaline (epinephrine) to facilitate the dissection and to limit bleeding.

2. Make a circumferential incision through the mucosa 1 cm proximal to the dentate line. Identify the white annular fibres of the rectal wall lying deep to the submucosa.

3. Develop the submucosal plane circumferentially using either scissor dissection or electrocautery until you reach the apex of the prolapse.

4. Continue the dissection back up inside the prolapsed rectum until close to the level of the anus. Unless you do this, only half of the prolapse will have been treated.

5. Re-approximate the mucosal edges using interrupted 2/0 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) sutures, which are also used to plicate the denuded rectal wall. Ensure that each suture takes several bites of the rectal wall in order to obliterate any potential dead space beneath the mucosa.

6. The plicated rectal wall returns to the pelvis and lies above the sphincter, preventing further prolapse.

FAECAL INCONTINENCE

Appraise

1. Determine the cause of faecal incontinence. If the anal sphincter is normal consider causes such as faecal impaction or irritable bowel syndrome. If the anal sphincter is abnormal consider the possibility of a congenital abnormality, complete rectal prolapse (see above), a lower motor neurone lesion, disruption of the sphincter ring due to trauma (including surgical and obstetric trauma) or muscle atrophy.

2. Operative treatment may be employed for the correction of some congenital abnormalities, complete rectal prolapse and simple disruption of the external sphincter (sphincter repair). Severe incontinence may need to be treated with the implantation of an artificial bowel sphincter. Sacral nerve stimulation is an alternative approach which is gaining in popularity.

3. Disruption of the sphincter ring may be suggested by a history of trauma – accidental, obstetric or surgical – and diagnosed by detecting a defect in the sphincter ring using endoanal ultrasound.

INJECTION OF BULKING AGENTS

1. The use of polytetrafluoroethylene (Teflon or polytef) was first reported in the context of a weakened or defective internal anal sphincter muscle by Shafik in 1993.

2. Injection of PTQ (silicone based) implants is now licensed in the UK. Reports on the use of other substances in faecal incontinence have been limited. Most substances have limited, if any, durability whether injected submucosally, intramuscularly or into the intersphincteris space.

3. The use of radiofrequency ablation has been employed as an alternative in the USA, but is not currently in use in the UK. It uses circumferential treatments to produce scarring of the anal canal.

Prepare

1. The patient should be put onto laxatives 2 days pre-injection, to continue for a week after injection.

2. An enema can be given preprocedure.

3. If the procedure is to be performed under local anaesthesia, a local anaesthetic cream can be used prior to injection of the anaesthetic agent.

4. Antibiotics are given intravenously at the time of the first injection and continued orally for a week after.

Action

1. There is little agreement on the optimal injection methodology.

2. The patient may be in the prone jack-knife, lithotomy or left lateral position.

3. Injections are sometimes given circumferentially in all patients and sometimes only into a specific site in those with a single internal anal sphincter defect.

4. Trans-sphincteric injection may reduce infection when compared to direct anal canal injection.

5. The site of the injection may be guided by the index finger to avoid any dispersal of product; however, some centres prefer to use a retractor or ultrasound guidance.

OVERLAPPING SPHINCTER REPAIR

Prepare

1. Order a full bowel preparation.

2. The patient is given a general anaesthetic and placed in the supine position if construction of a loop sigmoid colostomy is required (see Chapter 13). Then place the patient in the lithotomy position for the sphincter repair.

Action

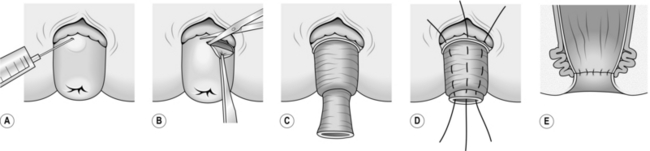

1. Make an incision following the slight pigment change seen around the anus. Centre it on the point of injury and extend it through 180° (Fig. 14.27).

2. Dissect out into ischiorectal fat. This means that the anal sphincter now lies between the depths of the wound and the anal canal (Fig. 14.28).

3. For an anterior, usually obstetric, injury mobilize the anus from the vagina. It helps to place two fingers in the vagina and two Allis forceps on the anal margin of the wound. The plane lies fractionally posterior to any large veins (because these will be paravaginal veins) (Fig. 14.29).

4. Split the muscle scar down its length and develop the plain between the anal mucosa and the muscle on either side.

5. After sufficient mobilization you can achieve a muscle overlap of about 2 cm, extending the length of the anal canal. Suture with 2/0 polydioxanone (PDS) (Fig. 14.30).

6. When possible, close the wound. Otherwise leave it open to heal by second intention (Fig. 14.31).

SACRAL NERVE STIMULATION

1. This is performed in two stages: a temporary testing phase and a permanent implant for those patients who are found to gain benefit during the testing phase.

2. There is no need for any bowel preparation.

3. The patient is given a general anaesthetic without muscle relaxants and lies in the prone jack-knife position. The anus and the big toes should be visible.

TEMPORARY TEST WIRE INSERTION

Action

1. Mark out the bony landmarks for the position of the S3 foramina. They are typically 1 cm cephalad to the crest of the sacrum and 1 cm lateral to the midline.

2. Insert the 20 G, 3.5-inch (9-cm) spinal insulated needles (Medtronic 041828–004) into S3 on either side, and find the best response to stimulation using an external, hand-held neuro-stimulator (Medtronic Model 3625 Screener). The current used for stimulation usually ranges from 0.5 to 2 mA at a rate of 20 Hz and a pulse width of 200 seconds.

3. Response to the stimulus is assessed clinically, looking for deepening and flattening of the buttock groove from lifting and dropping of the pelvic floor (known as a ‘bellows’ action) and a flexion of the big toe.

4. If the response if suboptimal it may be necessary to insert the needles into S2 or S4. Stimulation at the level of S2 usually causes a clamp-like contraction of the anal sphincter with rotation of the leg, ankle flexion and calf contraction. S4 is associated with a ‘bellows’ action and a pulling sensation on the perineum but not with any toe movement.

5. Using the foramen of maximal response, thread a temporary percutaneous stimulator test lead (Medtronic 3057) down through the needle and re-test the adequacy of the stimulation with the external stimulator and the wire. If a good response is still obtained slide the needle out over the wire, being very careful not to dislodge the wire. Secure the wire.

Postoperative

1. When the patient is awake and co-operative, attach the wire to the external stimulator (Medtronic Model 3625 Screener).

2. The stimulus employed for the 3-week temporary test phase is that which is the maximum comfortably tolerated by the patient, and usually ranges between 0.5 and 3 mA at 15 pulses/second with a pulse width of 210 microseconds.

THE PERMANENT IMPLANT

Action

1. The initial steps taken to find the correct foramen during the test are repeated. The permanent electrode (Medtronic 3093) is then inserted instead of the wire and this self-secures with barbs. This is then tunnelled subcutaneously out to the permanent stimulator which is implanted in the buttock.

2. The stimulator is left turned off until the patient is awake and responsive.

ARTIFICIAL BOWEL SPHINCTER (THE ACTICON)

Action

1. Make an incision similar to that for an anterior overlapping repair arcing around the front of the anus.

2. A tunnel is then created around the outside of the anal sphincters to accommodate the hydraulic cuff. Sizers can be used to assess the size of the cuff to be implanted. All parts of the sphincter are carefully primed with radio-opaque fluid, with the exclusion of all air bubbles prior to implantation.

3. A further ‘bikini-line’ incision a few centimetres long is then made on the side chosen for implantation of the pump (this depends on whether the patient is right- or left-handed).

4. The connector tube from the cuff is tunnelled up to the abdominal incision; the pump and the preperitoneal reservoir are implanted through the same incision. The pump sits in the labia majorum in women and in the scrotum in men. All three major components are connected by fully implanted silicone tubing.

5. The pump is squeezed to achieve cuff deflation via a temporary transfer of fluid into the balloon. A push-button device on the pump locks the pump closed until healing has occurred at about 6 weeks.

Beck, D.E., Wexner, S.D. Fundamentals of Anorectal Surgery, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1998.

Fielding, L.P., Goldberg, S.M. Rob and Smith’s Operative Surgery, 5th ed. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1993.

Goldberg, S.M., Gordon, P.H., Nivatvongs, S. Essentials of Anorectal Surgery. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1980.

Goligher, J.C. Surgery of the Anus, Rectum and Colon, 5th ed. London: Baillière Tindall; 1984.

Henry, M.M., Swash, M. Coloproctology and the Pelvic Floor, 2nd ed. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1992.

Keighley, M.R.B., Williams, N.S. Surgery of the Anus, Rectum and Colon, 2nd ed. London: Saunders; 1999.

Martin, M.-C., Givel, J.-C. Surgery of Anorectal Diseases. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1990.

Nicholls, R.J., Dozois, R.R. Surgery of the Colon and Rectum. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1997.

Phillips, R.K.S. Colorectal Surgery: A Companion to Specialist Surgical Practice. London: Saunders; 1998.

Sir Alan Parks Symposium Proceedings, Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1983. [(Supplement)].

Thomson, J.P.S., Nicholls, R.J., Williams, C.B. Colorectal Disease. London: Heinemann Medical Books; 1981.

Todd, I.P., Fielding, L.P., Rob and Smith’s Operative Surgery: Alimentary Tract and Abdominal 3. Colon, rectum and anus. 4th ed. Butterworths, London, 1983.