6. Ankylosing Spondylosis

Definition

Ankylosing spondylosis (AS) is rheumatoid arthritis of the spine found predominately in persons 20 to 40 years of age. It produces pain and stiffness as a result of inflammation of the sacroiliac, intervertebral, and costovertebral joints. The AS disease process may progress to complete spinal and thoracic rigidity.

Incidence

In the United States, the incidence of AS is approximately 0.1% to 0.2% of the population. Internationally, it accounts for 0.1% to 1.0% of the population. In persons with the HLA-B27 antigen, the incidence is 1% to 2%.

Etiology

The cause of AS is not fully understood. There seems to be a strong genetic predisposition, specifically involving human leukocyte antigen (HLA). HLA-B27 is believed to resemble and/or act as a receptor for a causative antigen (e.g., a type of bacteria). Currently, spurious evidence points to a bacterial causative agent, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae.

Signs and Symptoms

• Age younger than 40 years (usually)

• Chest tightness

• Decreased range of motion of costovertebral and costotransverse joints

• Difficulty breathing

• Elevated alkaline phosphatase

• Elevated C-reactive protein

• Elevated creatinine kinase

• Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate

• Fever

• Insidious onset of low back pain, with exacerbations and remissions

• Morning stiffness

• Pain and/or swelling of insertions of ligaments and tendons

• Peripheral enthesitis

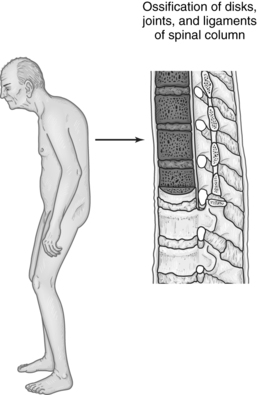

• Stooped forward, flexed head/neck position due to cervical and upper spine fusion

• Temporomandibular joint pain and decreased range of motion

• Weight loss

Medical Management

Preventive or prophylactic measures for AS are not available. AS is not surgically preventable, although surgical intervention may repair complications that occur as a result of the disease. The pain and inflammation of the joints are generally treated pharmacologically with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Sulfasalazine is used as an adjunct medication with reported effectiveness for patients with peripheral joint involvement and/or concomitant inflammatory bowel disease. Sulfasalazine is generally reserved for the patient who is unresponsive to NSAIDs or for whom NSAIDs are contraindicated. Methotrexate is typically the tertiary pharmacologic therapy for the patient with pain and symptoms inadequately controlled by NSAIDs and/or sulfasalazine.

|

| Ankylosing Spondylosis. Characteristic posture and primary pathologic sites of inflammation and resulting damage. |

Complications

• Atlantoaxial subluxation

• Death

• Gastrointestinal bleeding

• Inflammatory bowel disease

• Limited functional ability

• Pain

• Spinal cord compression

• Stiffness

• Ulceration of gastrointestinal mucosa

• Vertebral fractures

Anesthesia Implications

The most frequently affected vertebrae are those in the cervical spine. Atlantoaxial subluxation is a very real and serious potential problem for the anesthetist to encounter. The patient typically presents with significantly to severely limited range of motion (ROM) of the cervical vertebrae (neck). In addition, the temporomandibular joint may have a very limited ROM, resulting in a restricted ability to open the mouth. These factors may make direct laryngoscopy difficult or completely impossible. A laryngeal mask airway (LMA) may be an appropriate tool for securing the patient’s airway, depending on the proposed surgical procedure. In some cases, an LMA may be required to achieve tracheal intubation. The anesthetist must also be prepared to perform an awake fiberoptic intubation.

As a result of the fusion of the costovertebral joint, the chest wall may be permanently fixed in what appears to be an inspiratory position. Chest wall compliance is dramatically reduced and the functional residual capacity (FRC) is increased. These changes place considerably more importance on the diaphragm for the breathing cycle. The loss of chest wall compliance minimizes the contributions of the accessory muscles, particularly the intercostal muscles, for inspiration and expiration. Therefore any intrusion on diaphragmatic excursion seriously compromises the respiratory cycle of the patient with AS. For example, thoracic or extensive abdominal surgical procedures increase the stress placed on the diaphragm and, as a result, it may be necessary to provide prolonged ventilatory support. The expiratory phase of the ventilatory cycle should be longer than normal to reduce the possibility of lung hyperinflation.

Placement of spinal or epidural needles may be difficult or even impossible because of the ossification of the interspinous ligaments along with the development of bony ridges between the vertebrae (syndesmophytes).

Extreme care must be taken during patient positioning, even in the supine position. Spinal rigidity and osteoporosis significantly limit the degree of flexibility the patient has and the degree of movement that can be tolerated before significant spinal injury will be incurred. Even in the supine position, extra cervical support in the form of pillows or blankets may be required for the patient’s comfort. Placing the patient in either the lateral decubitus or the prone position makes it imperative that the anesthetist be more cautious, gentle, and deliberate in maintaining the head and neck in as nearly neutral a position as possible to avoid even minor trauma and the possibility of a devastating spinal injury.