128 Ankylosing spondylitis

Salient features

History

• Back stiffness and back pain: worse in the morning, improves on exercise and worsens on rest

• Symptoms in the peripheral joints (in ~40%), particularly shoulders and knees

• Onset of symptoms is typically insidious and in the 3rd–4th decade

• Extra-articular manifestations: red eye (uveitis), diarrhoea (GI involvement), history of aortic regurgitation, pulmonary apical fibrosis (worse in smokers).

Examination

• ‘Question mark’ posture (as a result of loss of lumbar lordosis, fixed kyphoscoliosis of the thoracic spine with compensatory extension of the cervical spine)

• Ask the patient to look to either side: the whole body turns when the patient does this.

• Examine the cervical, thoracic and lumbar spines (remember that cervical spine involvement occurs later in the disease and results in pain and a grating sensation on movement of the neck).

• Measure the occiput-to-wall distance (inability to make contact when heel and back are against the wall indicates upper thoracic and cervical limitation).

• Perform Schober’s test. This involves marking points 10 cm above and 5 cm below a line joining the ‘dimple of Venus’ on the sacral promontory. An increase in the separation of <5 cm during full forward flexion indicates limited spinal mobility.

• Examine for distal arthritis (occurs in up to 30% of patients and may precede the onset of the back symptoms). Small joints of the hand and feet are rarely affected.

• Measure chest expansion with a tape (<5 cm suggests costovertebral involvement).

• Tell the examiner that you would like to examine the following:

Questions

What are the diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis?

What investigations would you like to do in this patient?

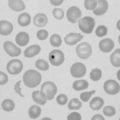

Anteroposterior view of sacroiliac joints and lateral radiographs of lumbar spine (Fig. 128.1A): the earliest changes are erosions and sclerosis of the sacroiliac joints. Later in the disease syndesmophytes may be found in the lumbosacral spine. In severe disease, involvement progresses up the spine, leading to a ‘bamboo spine’ (Fig. 128.1B). Although the New York criteria require a combination of clinical and radiographic features, the diagnosis should be suspected on the basis of inactivity, spinal stiffness and pain, with or without additional features.

How would you manage a patient with ankylosing spondylitis?

• Encourage exercise, particularly physical therapy, to preserve back extension

• NSAIDs, in particular indomethacin. Phenylbutazone is reserved for resistant cases

• Methotrexate and sulfasalazine

• Tumour necrosis factor blockers: etanercept, adalimumab, and golimumab. Etanercept decreases stiffness and pain and improvesoverall function, plus showing objective findings such as an increase in chest expansion and a decrease in the ESR (N Engl J Med 2002;346:1349)

• Surgical therapy, consisting of vertebral wedge osteotomy, is occasionally indicated

Advanced-level questions

What is the risk in those with a ‘bamboo’ cervical spine when driving?

Increased susceptiblity to whiplash injury and restricted lateral vision.