13 Angina pectoris

Salient features

History

• Have you ever had any pain or discomfort in the chest?

• How would you describe the chest discomfort (heavy, burning, tightness, stabbing, pressure)?

• Do you get this on walking at ordinary pace on the level or does it come when you walk uphill or hurry?

• When you get the pain/discomfort, do you stop, slow down or continue at the same pace?

• Does the pain/discomfort go away when you stand still? (It is typically relieved by rest or glyceryl trinitrate within 10 min.)

• Where do you get this pain? (Because angina is a visceral sensation, it is poorly localized and, therefore, patients rarely point to the location of their discomfort with one finger.)

• Does it radiate elsewhere (e.g. arms, jaw, epigastrium)?

• Does food or cold weather bring on the pain?

• Ask about risk factors such as smoking, diabetes, hypertension, family history of ischaemic heart disease.

• Ask about past medical history of coronary artery disease.

Questions

How is angina graded by the Canadian Cardiovascular Society?

There are four functional classes:

• I: angina occurs only with strenuous or rapid or prolonged exertion

• II: slight limitation of ordinary activity (e.g. climbing more than one flight of ordinary stairs at a normal pace and in normal conditions)

• III: marked limitation of ordinary activity (e.g. climbing more than one flight in normal conditions)

• IV: inability to carry out any physical activity without discomfort—anginal syndrome may be present at rest.

How would you investigate a patient with angina pectoris?

• Haemoglobin: anaemia aggravates angina

• Rest ECG to detect left ventricular hypertrophy, prior Q-wave MI or ST-T changes

• Rest echocardiogram is carried out only when there is clinical suspicion of aortic stenosis or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

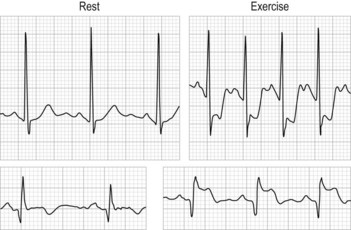

• Exercise ECG can precipitate symptoms, document workload at onset and record any associated ECG abnormality (≥1 mm of horizontal or downsloping ST-segment depression or elevation for ≥60 to 80 ms after the end of the QRS complex) or arrhythmia (Fig. 13.1)

• Exercise myocardial perfusion imaging or exercise echocardiography is used in patients where considerations of functional significance of lesions or myocardial viability are important or who have one of the following baseline ECG abnormalities:

• Coronary angiography: provides detailed anatomical information about site and severity of luminal narrowing caused by coronary atherosclerosis and less-common non-atherosclerotic causes such as coronary artery spasm, coronary anomaly, primary coronary artery dissection and radiation-induced coronary vasculopathy.

How would you treat a patient with chronic stable angina pectoris?

Treatment is remembered with the mnemonic ABCDE (Circulation 1999;99:2829–48).

A: aspirin, antianginal therapy and ACE inhibitor therapy. Aspirin has been shown to reduce the incidence of non-fatal MI and the overall incidence of cardiac events, although overall death rate and the incidence of fatal MI were similar to those obtained with placebo in the Swedish Angina Pectoris Aspirin Trial (SAPAT) study. Ramipril up to 10 mg once a day should be offered to all patients in view of the new HOPE trial. Antianginal therapy includes nitrates, ranalozine and nicorandril.

B: beta-blocker and blood pressure

What other treatments are there?

Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (with or without coronary stent)

• Complementary to drug treatment and surgery; no improvement in survival.

• Best results are achieved in discrete single-vessel coronary artery disease.

• The restenosis rate is ~30% at 6 months; for balloon angioplasty with stenting, restenosis is lower, ~20%.

• The ACME (Angioplasty Compared to Medicine) study showed that PTCA can offer better symptomatic relief than medical therapy in patients with single-vessel coronary artery disease, but is a much more expensive procedure and is associated with complications (including emergency and elective coronary bypass and second PTCA).

• The RITA (Randomized Intervention Treatment of Angina) study compared PTCA with CABG and found that both procedures have similar prognostic implications with risk of death or myocardial infarction similar in the two groups, but more patients in the PTCA group required a second revascularization procedure and more antianginal therapy.

Advanced-level questions

How would you follow a patient with stable angina in your clinic?

1 Has the patient decreased the level of physical activity since the last visit?

2 Have the patient’s anginal symptoms increased in frequency and become more severe since the last visit? If the symptoms have worsened or the patient has decreased physical activity to avoid precipitating angina, then he or she should be evaluated and treated according to either the unstable angina or chronic stable angina guidelines, as appropriate.

3 How well is the patient tolerating therapy?

4 How successful has the patient been in reducing modifiable risk factors and improving knowledge about ischaemic heart disease?

5 Has the patient developed any new comorbid illnesses or has the severity or treatment of known comorbid illnesses worsened the patient’s angina?

What changes in resting 12-lead ECG are consistent with coronary artery disease and suggest ischaemia or previous infarction?

In people without confirmed coronary artery disease in whom stable angina cannot be diagnosed or excluded based solely on clinical assessment alone, how would you manage the patient?

• Estimated likelihood 10–29%: CT calcium score as the first-line diagnostic investigation indicates:

• Estimated likelihood 30–60%: functional imaging as the first-line diagnostic investigation.

• Estimated likelihood 61–90%: invasive coronary angiography as the first-line diagnostic investigation may be considered.

How is exercise testing useful in determining the prognosis of chest pain?

• Low-risk subset: subjects who could complete 9 min of exercise using the Bruce protocol without evidence of ischaemic ST segment changes and achieve a maximal sinus heart rate in excess of 160 beats/min. These were found to have a 1-year survival rate of 99% and a 4-year survival rate of 93%. This means that cardiac catheterization and CABG can be deferred.

• High-risk subset: those who were forced to stop exercising in stages I or II (under 6 min); survival rate was 85% at 1 year and 63% at 4 years.

What do you understand by significant coronary artery disease?

What the indications for CABG in stable angina?

ACC/AHA guidelines 2004 (Circulation 2004;110:e340–437):

1 Recommended in patients with:

What do you understand by the term syndrome X?

• Syndrome X, or microvascular angina, is the presence of classic angina and ST depression on exercise stress testing and a normal coronary angiogram in the absence of any other demonstrable cardiac abnormalities.

• Reaven syndrome or ‘endocrine’ syndrome X is the association of insulin resistance, hypertension, and increased very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) and decreased HDL cholesterol concentrations in the plasma.