CHAPTER 3 Anesthetic Considerations

Introduction

Patient Preparation and Monitoring

♦ Most patients are moderate to high anesthesia risks (i.e., American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA] physical status class 3), and abnormal pulmonary function test results are expected.

♦ Reassuringly prepare the patient to anticipate that breathing will be uncomfortable on waking due to the effect of chest tubes and lung reexpansion.

♦ Patients who have had neoadjuvant radiation therapy or chemotherapy must be identified in advance and kept on the lowest acceptable FIO2 because they are more susceptible to hyperoxic lung injury.

Double-Lumen Endotracheal Tube Placement

Applications

♦ DLTs are required for most thoracic cases: wedge resection, lobectomy, pneumonectomy, lung reduction, pleurodesis, decortication, and esophagectomy.

♦ They are not required for mediastinoscopy, sympathectomy, or pericardial window (i.e., subxyphoid approach).

Routine Intubation

1. Insert the Mac blade into the right side of the mouth, and use the flange to sweep the tongue over to the left.

2. Advance the tip of the blade into the vallecula, and elevate the blade to reveal the vocal cords. In some patients, the view improves with the tip of the blade beneath the epiglottis.

3. Bend or curve the DLT at an angle of 30 to 45 degrees about 6 to 8 cm from the tip, and insert it from the right side of the mouth so that the tip approaches the vocal cords.

4. Depending on the relationship of the bronchial tip and the surrounding structures, one of two approaches is necessary:

5. Because the DLT is often anteriorly directed at this stage, the leading edge may catch on the tracheal rings, preventing advancement of the tube. Additional gentle rotation and pressure may be necessary to “screw” the DLT into the mid-trachea, and it may be necessary to pass a fiberoptic bronchoscope through the bronchial lumen to help guide the DLT tip through the tracheal rings and into the appropriate bronchus.

Difficult Intubation

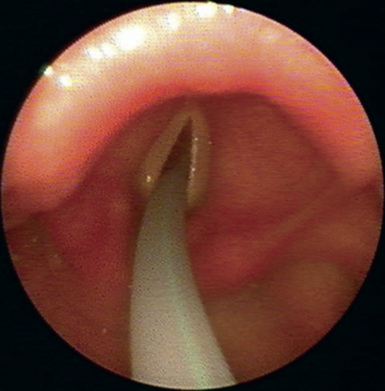

♦ Use of a DLT exchange catheter facilitates placement of a DLT in patients with an anterior larynx, limited aperture, or other difficult airway situations (Figure 3-1). The exchange catheter may be guided into the trachea using direct video laryngoscopy or advanced through a previously placed single-lumen endotracheal tube. The DLT is then passed over the catheter into the trachea. Care must be taken to pass the exchange catheter tip gently just past the vocal cords to avoid tracheal injury.

Achieving Optimal DLT Placement

Choice of Right versus Left DLT

♦ There is no risk of inadvertently stapling the cuff of a left DLT during left lobectomy or pneumonectomy.

♦ A complete view of the carina and the mainstem bronchus of the operated lung is obtained during bronchoscopy.

♦ Bronchoscopy through the tracheal lumen to check the distal cuff position does not interrupt ventilation of the nonoperated lung.

♦ If the tracheal (proximal) cuff is damaged by the patient’s teeth during insertion, lung isolation is still accomplished by the intact distal cuff.

♦ If a left DLT is used for left lung surgery, it is possible for pressure on the operated lung to occlude the tracheal lumen, which is ventilating the right lung, or to push the bronchial cuff back into the trachea.

♦ Right DLTs are easy to insert because the path to the right mainstem bronchus is more direct. A contralateral tube is imperative when a sleeve resection is performed (e.g., if a left-sided tube is used when the left mainstem bronchus is open during a bronchial sleeve), the tube interferes with suturing and the patient is not ventilated well.

Troubleshooting after Initial Insertion

♦ In 5% to 10% of cases, a left DLT goes down the right mainstem bronchus, despite the usual leftward rotation, as it is advanced. Withdraw the tube into the trachea, and advance it into the left bronchus under direct FOB vision.

♦ When the patient is turned lateral and flexed, the DLT usually retracts cephalad at least a centimeter and may need to be advanced to avoid herniation of the distal cuff over the carina. This is especially likely in edentulous patients. It is always easier to pull a DLT back than to advance it after it has become warm and flexible.

♦ Hypoxemia is usually a sign of an improperly placed tube; we rarely find it necessary to use continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for the operated lung or positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) greater than 5 cm to the nonoperated lung. During lobectomy, the oxygen saturation always improves after clamping of the arterial blood supply to the lobe.

Fiberoptic Bronchoscopy and Tracheobronchial Anatomy

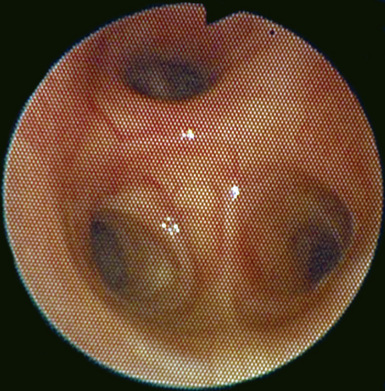

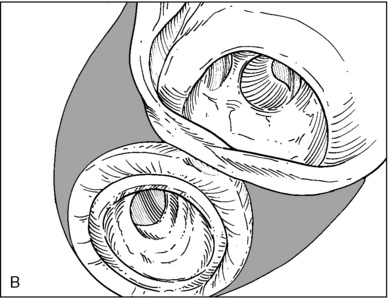

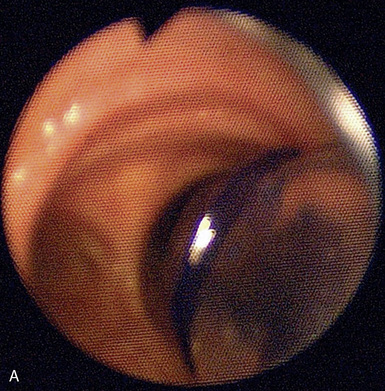

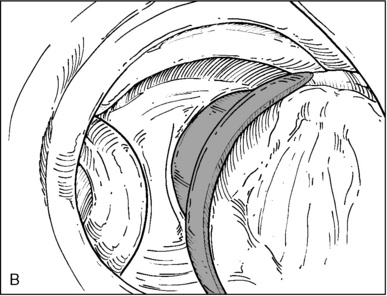

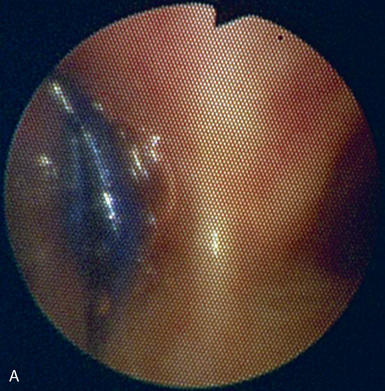

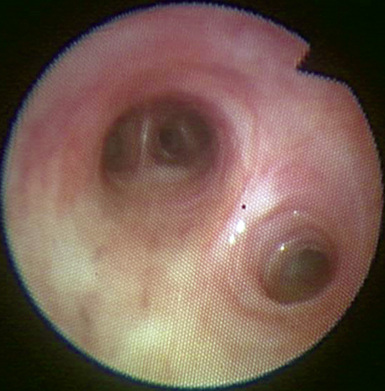

♦ Right bronchus intermedius and bifurcation into the right middle lobe (RML) and right lower lobe (RLL) (Figure 3-5)

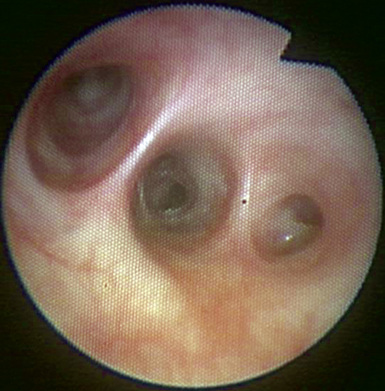

♦ Left mainstem bronchus, carina, and bifurcation into the left upper lobe (LUL) and left lower lobe (LLL) (Figure 3-6)

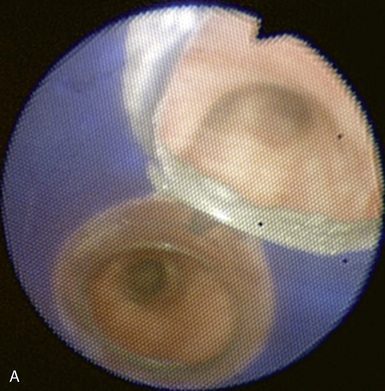

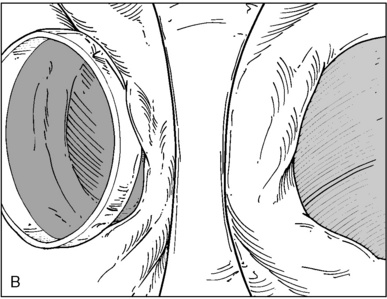

♦ Optimally placed right DLT

♦ Optimally placed left DLT

Figure 3-7 The left lower lobe bronchus has one superior segment and three (sometimes four) basal segments.

Induction, Maintenance, and Emergence from Anesthesia

♦ All medication choices are geared toward prompt emergence from anesthesia and extubation in the operating room whenever possible.

♦ Reduce FIO2 in any patient who has received neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy to reduce the risk of hyperoxic lung injury; oxygen saturation of 86% to 90% is acceptable during one-lung ventilation.

Induction

♦ Propofol is well tolerated by most patients, although we often use reduced doses; etomidate is appropriate for patients with compromised cardiac function or hypovolemia.

Maintenance

♦ Clamp the tracheal lumen of the DLT well before surgical entry to the thorax to allow the lung time to deflate; confirm tube placement with FOB after lateral positioning, and suction the operated lung as necessary.

♦ Dexamethasone (8 to 10 mg IV) helps to reduce vocal cord edema, diminish airway reactivity, and prevent postoperative nausea.

♦ Desflurane is a useful inhaled agent because it can be rapidly titrated on and off, and it acts as an effective bronchodilator. Desflurane reduces hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction but not to a clinically significant degree.

Intraoperative Issues and Caveats

♦ Short-lived fluctuations in blood pressure are common because of variations in the level of surgical stimulus, mechanical pressure on the heart or great vessels, and relatively dry fluid status.

♦ Pharmacologic support of low blood pressure is better than giving large quantities of crystalloid. Hypertension can be managed acutely with small doses of propofol or esmolol; use longer-acting antihypertensive agents only with caution until surgery ends.

♦ Intraoperative arrhythmias are often secondary to instrumentation and resolve when manipulation is stopped.

Ventilation Parameters

♦ Monitor to ensure a peak airway pressure (PAP) of less than 35 cm H2O and a plateau pressure of less than 25 cm H2O.

♦ Use pressure-controlled ventilation for patients with reduced lung compliance or other risk factors for acute lung injury:

Exposure to drugs associated with pulmonary toxicity, such as amiodarone, bleomycin, cyclophosphamide, tocainide, crack cocaine, and heroin

Exposure to drugs associated with pulmonary toxicity, such as amiodarone, bleomycin, cyclophosphamide, tocainide, crack cocaine, and heroin

Exposure to drugs associated with pulmonary toxicity, such as amiodarone, bleomycin, cyclophosphamide, tocainide, crack cocaine, and heroin

Exposure to drugs associated with pulmonary toxicity, such as amiodarone, bleomycin, cyclophosphamide, tocainide, crack cocaine, and heroinEmergence

♦ Reinflate the operative lung gradually; manual ventilation is the best means of controlling airway pressure.

♦ Consider allowing the patient to resume spontaneous ventilation during closure of the subcutaneous tissue and skin.

♦ The use of pressure support with or without synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) facilitates spontaneous ventilation and lung reinflation.

♦ Extubate patients awake in the semi-sitting position if they are obese or were difficult to intubate.

♦ Consider deep extubation in the lateral position for selected patients (e.g., normal weight, easy airway); this has the advantage of reducing cough, bronchospasm, hypertension, and tachycardia.

Procedure-Specific Pearls and Pitfalls

Mediastinoscopy

♦ Significant blood loss rarely occurs but can be massive and can require median sternotomy for control.

♦ Place the pulse oximeter sensor and arterial catheter (if used) on the patient’s right. If the mediastinoscope occludes the brachiocephalic artery, diminished blood flow to the right arm can be recognized promptly and the surgeon alerted so that the duration of reduced flow to the right carotid artery can be minimized.

Bilateral Thoracic Sympathectomy

Esophagectomy

♦ Depending on the site of the lesion, the patient may require right video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) or right thoracotomy in addition to laparotomy.

Pleurodesis and Decortication

♦ Pleurodesis and decortication are often undertaken in very ill patients with metastatic cancer, chronic pleural effusion, empyema, or hemothorax.

Bilateral Lung Volume Reduction Surgery

♦ Instruct the patient in the use of pursed-lip breathing after surgery to augment pulmonary function by supplying auto-PEEP.

♦ A thoracic epidural catheter should be placed before surgery unless there is a contraindication (see “Postoperative Analgesia”).

♦ Gentle induction works best, with reduced propofol dosing, a nondepolarizing muscle relaxant, and an inhaled agent for bronchodilation.

♦ Highly compliant lungs with bleb formation reach excessive tidal volumes easily; avoid aggressive mask ventilation during induction.

♦ Maintain pressure-controlled ventilation with initial peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) settings of 12 to 14 cm H2O (preferred). PIP greater than 20 cm is rarely necessary.

♦ Allow higher than normal Pco2 (i.e., permissive hypercapnia) with slower inspiratory and expiratory cycling of the ventilator to reduce the risk of barotrauma and air trapping. Oxygenation is seldom a problem.

♦ Reinflation of the first lung should be accomplished by manual ventilation with pressures of less than 20 cm, gradually increasing each breath until the lung is expanded. Although the surgeon may request higher pressure to test the suture line, it is important to avoid causing another bleb to rupture.

♦ Assess suture line leaks by using a volume meter attached to the anesthesia circuit. At a reasonable PIP, measure the difference between inspiratory and expiratory volumes. Too great a difference implies that the suture line must be inspected for a leak. Some air leak is to be expected; the amount varies according to the patient’s lung volumes.

♦ As operation begins on the second side, the ventilated lung is the previously reduced lung. Compliance is often decreased, and a lower tidal volume must be tolerated to avoid excessive PIP.

Postoperative Analgesia

Analgesia for Routine Thoracoscopic Cases

♦ In our institution, less than 5% of thoracoscopic cases convert to open thoracotomy, and we do not place epidural catheters for routine single-lung VATS procedures.

♦ The surgeons infiltrate the skin with local anesthesia before incision and often perform thoracic intercostal nerve blocks from T2 to T11 before wound closure.

♦ The PACU nursing staff plays a vital role in titrating narcotic analgesia. Too little can cause the patient to splint and refuse to cough due to pain; too much can easily result in carbon dioxide retention. Small incremental doses work best, such as hydromorphone (0.2 to 0.5 mg IV) or fentanyl (25 to 50 mcg IV).

Thoracic Epidural Analgesia

♦ We place epidural catheters preoperatively in patients undergoing open thoracotomy, pneumonectomy, lung volume reduction surgery, bilateral VATS, and rib or chest wall resection.

♦ About 5% of video-assisted lobectomies are scheduled as possible open thoracotomies due to previous neoadjuvant radiation therapy or chemotherapy, Pancoast tumor, chest wall involvement, or the need for sleeve resection; these patients receive epidural catheters.

♦ Epidural placement before induction of general anesthesia produces improved analgesia because the epidural can be activated before the conclusion of surgery.

♦ The epidural catheter is usually inserted at the mid-thoracic level. Placement at a more cephalad level does not block pain from the chest tube insertion sites.

♦ In the event of unanticipated conversion of VATS to open thoracotomy, some anesthesiologists place an epidural catheter before emergence from anesthesia, with minimal or reversed neuromuscular blockade. Others prefer to awaken the patient and insert the epidural in the PACU.

♦ Anesthesiologists disagree about whether it is ever justifiable to insert a thoracic epidural catheter in an unconscious adult patient who cannot report pain or paresthesia.

♦ We make limited use of the epidural catheter during surgery except to give a test dose of local anesthetic and a loading dose of 2.5 to 4 mg of preservative-free morphine. A fully activated epidural increases the risk of intraoperative hypotension.

♦ Because fluid administration is kept to a minimum for most thoracic patients, especially those undergoing pneumonectomy, blood pressure may need support with a low-dose infusion of phenylephrine for the first 24 hours.

♦ Near the conclusion of surgery, we administer epidural fentanyl (50 to 100 mcg) with 0.25% bupivacaine or 1% lidocaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine (4 to 6 mL). A continuous infusion is started after the patient arrives in the PACU, usually consisting of fentanyl (5 to 10 mcg/mL) and bupivacaine (0.05% to 0.0625%) at 3 to 6 mL/hr.