CHAPTER 28 Anesthesia, Pain Management, and Early Discharge for Partial Knee Arthroplasty

The implementation of specialized clinical pathways in joint replacement has simultaneously decreased the length of hospital stay while significantly decreasing complications.

The implementation of specialized clinical pathways in joint replacement has simultaneously decreased the length of hospital stay while significantly decreasing complications. We have developed newer perioperative anesthesia and rehabilitation protocols and combined them with a minimally invasive approach to partial knee replacement in order to hasten recovery and perform outpatient partial knee replacement.

We have developed newer perioperative anesthesia and rehabilitation protocols and combined them with a minimally invasive approach to partial knee replacement in order to hasten recovery and perform outpatient partial knee replacement.Historical Perspective

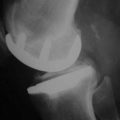

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty was originally popularized in the 1970s, promising minimal bone sacrifice and the potential ease of future revision to a total knee arthroplasty, if required. Unfortunately, an incomplete understanding of appropriate indications and surgical techniques, combined with flawed early prosthetic designs, resulted in a high rate of failure. Subsequently, unicompartmental knee arthroplasty was all but abandoned in the United States by the late 1980s. Fortunately, renewed interest in the concept was initiated by Repicci and colleagues,1,2 who in the 1990s described a minimally invasive technique for unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Subsequently, unicompartmental knee arthroplasty has increased in usage secondary to a combination of interest in less invasive knee arthroplasty1–3 and reports from multiple centers of survivorship that rivals that of total knee arthroplasty in appropriately selected patients.4

In the past decade, efforts have been made to improve the short-term outcomes of both total knee arthroplasty and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty with respect to pain control and early functional recovery with the implementation of minimally invasive surgical techniques.5–10 The evolution of many orthopedic procedures has had this progression. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction has evolved from an inpatient to an outpatient procedure. In addition, spinal diskectomy has also had similar changes over the past decade. As in these procedures, minimizing soft tissue trauma is one part of a greater protocol that has led to decreased inpatient needs and, at our institution, the now commonplace outpatient unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. A comprehensive perioperative approach is essential to allow same-day discharge of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty patients. This paradigm shift involves not only the patient and surgeon, but also the patient’s family, the hospital, anesthesia team, therapists, and nursing staff. A successful protocol and pathway includes pain management, decreasing medication side effects, and accelerated therapy that is delivered in a timely fashion.

Preoperative Planning

Preoperative planning occurs in many stages and is the most important part of the process. It begins long before the day of surgery and includes much more than the historic medical clearance and implant choice that we have become accustomed to. The main components are planning, perioperative education, teamwork, and follow-through. The entire plan is customized for each individual patient and is created in the office at the time the patient decides to have surgery. After choosing the surgery date, the patient’s medical history is carefully scrutinized to identify relevant problems such as cardiac, pulmonary, thromboembolic, anticoagulation, and any other issues that may require more thorough preoperative investigation or an altered postoperative management. All patients attend a comprehensive educational class prior to surgery. During the same visit to our medical center for the teaching class, the patient’s medical clearance appointments and laboratory tests are scheduled, as well as an appointment to donate a unit of autologous blood. Each patient is given a complete packet of information in the office when they sign up for surgery. The contents follow a clear and logical format—these are summarized in Box 28–1.

Box 28–1 Summary of Patient Information Packet

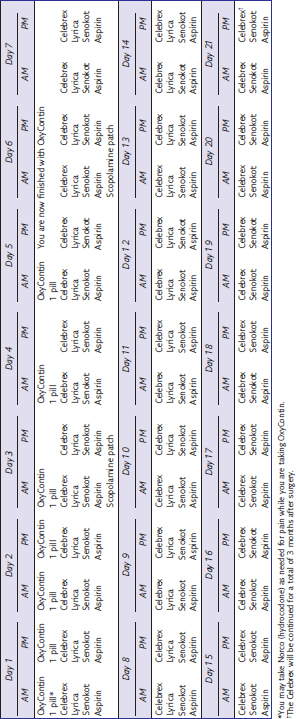

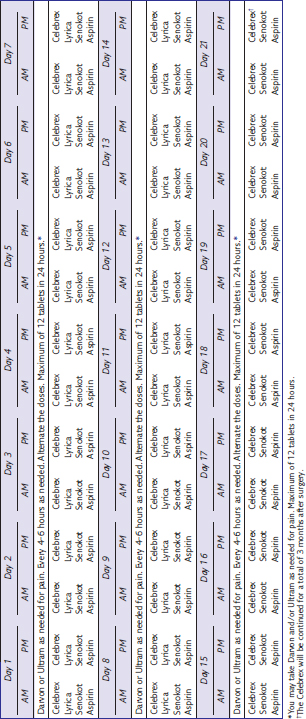

The most significant hurdle to outpatient partial knee arthroplasty is effective pain management. Much of the difficulty stems from patient fears and beliefs. A significant portion of the preoperative class therefore focuses on pain control strategies. The patients receive their postoperative pain medications from the hospital pharmacy at the time of the class to avoid any unnecessary delays the day of surgery. We employ a long-acting narcotic for baseline pain control, a short-acting breakthrough narcotic, and a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory. In addition, we proactively reduce side effects such as nausea and constipation. The postoperative medication strategy is outlined in Tables 28–1 and 28–2. Table 28–1 is the routine table we use for our patients, while Table 28–2 is for the elderly patient or the patient who cannot or will not take oxycodone (OxyContin). Furthermore, it is difficult to predict the most appropriate dose of oral narcotic pain medication, even when considering the patient’s weight and age. Therefore, all patients are asked to take one dose of the strongest pain medication they will take the week before surgery and to report any side effects. The postoperative dose can then be modified appropriately. The stool softener and antinausea medication are initiated prior to surgery and continued as shown in Tables 28-1 and 28-2. Finally, the patients are given two additional sheets that give an overview (Table 28–3) and a detailed view (Box 28–2) of their medications so that they understand what to take, when, and why.

| Long-acting narcotic | OxyContin (oxycodone HCl, controlled release; Purdue Pharma L.P., Stanford, CT) |

| Short-acting narcotic | Norco (hydrocodone/acetaminophen) |

| COX II anti-inflammatory | Celebrex (celecoxib; Pharmacia/Pfizer, Chicago, IL) |

| Antinausea agent | Scopolamine patch |

| Stool softener | Senokot S (to start 2 days prior to surgery) |

Box 28–2 Medication Explanation for Patients

Successful outpatient partial knee surgery not only requires careful planning and preparation, but also requires cooperation between the patient and surgical team. This team includes the surgeon, office staff, anesthesia team, and the hospital team of nurses and therapists. For patients to be discharged the day of surgery, the patient must meet specific goals. To meet these requirements in a timely fashion requires an early surgical start time for patients who are planning to go home the same day. A strategy is utilized for prophylactic prevention of and treatment of pain, hypovolemia, and nausea. This approach is necessary in minimizing any symptoms or problems that would otherwise delay recovery. Preoperative medication protocols are employed to establish baseline blood levels of both narcotic and anti-inflammatory medication. Most patients take 10 mg of OxyContin and 400 mg of celecoxib (Celebrex) with a sip of water the morning of surgery. Most patients are placed on the standard postoperative protocol (see Table 28–1). Patients who are unable to take narcotics, had an adverse reaction to the trial dose of medication, or are extremely elderly are placed on an alternative pathway (see Table 28–2) and therefore just take 400 mg of Celebrex with a sip of water the morning of surgery.

Cooperation between the surgical team and the anesthesia team is a very important aspect of successful outpatient partial knee surgery. The anesthetic goal is appropriate intraoperative pain relief that minimizes postoperative symptoms.11,12 While there are many anesthetic choices that allow outpatient partial knee replacement, our patients receive a straight bupivacaine epidural in the holding area prior to entering the operating room. A small dose of midazolam (Versed) is administered in conjunction with epidural placement. Intraoperative sedation is accomplished with propofol, which is titrated as needed for the individual patient. Narcotic use is avoided, or at least minimized as much as possible, to avoid unwanted side effects, which typically include increased nausea and sedation. Another important strategy that includes the anesthesia team is the prevention of nausea and hypovolemia. A big part of the technique begins by restricting narcotic use intraoperatively. To prevent nausea, the anesthesiologist administers 20 mg famotidine (Pepcid) IV, 4 mg ondansetron (Zofran) IV, and 10 mg metoclopramide (Reglan) IV during the surgery. This combination helps to prevent nausea postoperatively. The anesthesiologist is encouraged to aggressively manage fluid balance. To aid in this cause, if the patient has donated autologous blood, it is transfused intraoperatively to prevent anemia and hypovolemia. If the patient has not donated autologous blood, patients are typically given a fluid bolus of hetastarch in sodium chloride (Hespan) at the conclusion of the surgery. Alternatively, as another method to prevent fluid loss, a re-transfusion device can be utilized.

The surgical technique itself plays a pivotal role in our outpatient partial knee protocol. Multiple minimally invasive techniques have been described for partial and total knee arthroplasty.1-3,5,6,8,10,13 These surgical techniques all share the common goal of limiting soft tissue injury in order to limit pain and allow early function after surgery. These strategies include making in situ bone cuts, not dislocating the knee or the patella, and preserving the quadriceps mechanism.

Postoperative Management

The patient’s diet is advanced almost immediately, and patients typically receive lunch in the early afternoon. The epidural catheter and urinary catheter are removed 6 hours after surgery. A 10-mg dose of OxyContin is administered 2 hours prior to epidural removal as a bridge for pain management. Patients who experience significant postoperative pain may receive 30 mg ketorolac intramuscularly. This pain management protocol minimizes narcotic use and side effects while effectively controlling pain. Patients are required to pass physical therapy prior to discharge. Therapy sessions typically begin in the early afternoon, depending on when the patient reaches the floor. It is imperative that patients are not experiencing hypotension or nausea when therapy is initiated. If they are experiencing either of these symptoms, we temporarily hold therapy until we correct the problem (Table 28–4). Therapy starts by sitting the patient on the side of the bed and progressing if he or she is symptom free. Ambulatory aids are used as needed as determined by the therapist. Physical therapy goals include walking 150 feet and managing a single flight of stairs. Achieving these goals takes approximately 30 minutes.

| Preemptive | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|

| Nausea | Minimize or avoid opioids Ondansetron (Zofran) or scopolamine patch Keep adequate hydration Steroids |

Metoclopramide (Reglan) Hydration (Zofran does not work well for treatment) |

| Hypotension (orthostatic) | Adequate hydration | Hydration Ephedrine |

| Hypotension (drug induced) | Avoid opioids | Reverse drug Wait Hydration |

| Pain | Anti-inflammatories and opioids prior to surgery Local injection for bridge Start oral medications in recovery room Avoid PRN dosing |

Opioids for breakthrough Ketorolac (Toradol) |

Discharge is dependent not only on physical therapy, but also upon pain and nausea control. The discharge instructions are reviewed and patients are instructed not to operate a motor vehicle if they are using any narcotic medication. The patients must have a family member or friend to drive them home and stay with them during the immediate postoperative period. The patient’s postdischarge care plan is clearly delineated at the teaching class and outlined on written materials that the patients take home. Patients are encouraged to work on range of motion on their own and are weight bearing as tolerated. They already have their postoperative long-acting and short-acting pain medications. The 1-week follow-up appointment is prearranged and they are seen again at 3 and 6 weeks. A wide variety of anticoagulation protocols exist, and any of them may be utilized in conjunction with rapid rehabilitation techniques. We choose to use 325 mg of aspirin twice a day for 3 weeks after surgery. We also use graded compression stockings for the first 3 weeks. Several other aspects of the overall protocol also decrease the rate of thrombosis.14 The minimally invasive techniques themselves do not require patellar eversion, hyperflexion, or tibial dislocation. Autologous blood donation and epidural anesthesia contribute as well.

Results

We have previously reported results with outpatient partial and total knee arthroplasty.5,6,13 The successes of our initially conservative selection criteria have led us to expand the indication to all patients. In fact, in our most recent report,13 we found that 94% of the partial and total knee arthroplasties performed before noon were done on an outpatient basis. In this study of all comers, we assessed the feasibility and perioperative complications following outpatient total knee and unicompartmental knee replacement where no patient was excluded. To accomplish these goals, a minimally invasive surgical technique, improved perioperative anesthesia, and an expedited rehabilitation protocol were developed. One hundred twenty-one consecutive patients who had primary partial or total knee replacement completed by noon were prospectively studied.13 While no patient was excluded by the investigator, 10 patients refused participation. The remaining 25 unicompartmental knee arthroplasty and 86 total knee arthroplasty patients (111 total) followed the comprehensive perioperative clinical pathway described above (see Box 28–3), which included preoperative teaching, regional anesthesia, preemptive oral analgesia, and preemptive antiemetics. In addition, a rapid rehabilitation pathway with full weight bearing and range of motion was implemented within a few hours after surgery. Only if standard discharge criteria were met did the patient have the option of discharge to home the day of surgery.

Twenty-four of the 25 unicompartmental knee replacement patients (96%) and 80 of the 86 total knee replacement patients were discharged directly to home on the day of surgery.13 The remaining seven patients were hospitalized overnight and discharged the next day. The only unicompartmental knee arthroplasty patient who required overnight stays experienced nausea that could not be adequately controlled on the day of surgery. Four patients who had undergone total knee replacement remained hospitalized due to difficulty with pain control; all had their surgeries completed between 11:00 am and noon. One total knee patient had chest pain that required a workup for myocardial infarction, which was negative, and another total knee patient chose not to leave the hospital due to apprehension and fear of discharge. All of these seven patients successfully and easily met discharge criteria by the morning of postoperative day 1 and were discharged to home at that time. There were no statistically significant differences with regard to average age (p = .46), body weight (p = .47), or body mass index (p = .17) between the 104 patients who were successfully treated as outpatients and the seven patients who required an overnight stay. There were no readmissions or emergency room visits within the 3 months following surgery for any of the unicompartmental patients. There were no deaths, cardiac events, or pulmonary complications during this study. This study has shown that the comprehensive perioperative clinical pathway that we have developed and described above not only is effective for allowing early discharge and rehabilitation for unicompartmental knee surgery patients, but also is safe.13

1 Repicci JA, Eberle RW. Minimally invasive surgical technique for unicondylar knee arthroplasty. J South Orthop Assoc. 1999;8:20-27. discussion appears in J South Orthop Assoc 1999;8:27

2 Romanowski MR, Repicci JA. Minimally invasive unicondylar arthroplasty: eight year follow-up. J Knee Surg. 2002;15:17-22.

3 Gesell MW, Tria AJ. MIS unicondylar knee arthroplasty: surgical approach and early results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;428:53-60.

4 Berger RA, Menghini RM, Jacobs JJ, et al. Results of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty at a minimum of ten years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2005;87:999-1006.

5 Berger RA, Sanders S, Gerlinger T, et al. Outpatient total knee arthroplasty with a minimally invasive technique. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20(3 Suppl):33-38.

6 Berger RA, Sanders S, D’Ambrogio E, et al. Minimally invasive quadriceps-sparing TKA: results of a comprehensive pathway for outpatient TKA. J Knee Surg. 2006;19:145-148.

7 Rosenberg AG. Anesthesia and analgesia protocols for total knee arthroplasty. Am J Orthop. 2006;35(7 Suppl):23-26.

8 Scuderi GR. Minimally invasive total knee arthroplasty: surgical technique. Am J Orthop. 2006;35(7 Suppl):7-11.

9 Scuderi GR. Preoperative planning and perioperative management for minimally invasive total knee arthroplasty. Am J Orthop. 2006;35(7 Suppl):4-6.

10 Goble EM, Justin DF. Minimally invasive total knee replacement: principles and technique. Orthop Clin North Am. 2004;35:235-245.

11 McGuire DA, Sanders K, Hendricks SD. Comparison of ketorolac and opioid analgesics in postoperative ACL reconstruction outpatient pain control. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:653-661.

12 White PF. Management of postoperative pain and emesis. Can J Anaesth. 1995;42:1053-1055.

13 Berger RA, Kusuma SK, Sanders SA, et al. The feasibility and perioperative complications of outpatient knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:1424-1430.

14 Berend KR, Lombardi AVJr. Multimodal venous thromboembolic disease prevention for patients undergoing primary or revision total joint arthroplasty: the role of aspirin. Am J Orthop. 2006;35:24-29.