CHAPTER 3 Anesthesia in aesthetic surgery

History of ambulatory anesthesia

The origins of anesthesia began with a series of events in the mid 1800s. While training in New York City, Crawford Long experienced the recreational use of ether and nitrous oxide during student parties: the so-called “ether frolics”. After starting his practice, he applied the use of diethyl ether to anesthetize a patient during removal of two small tumors from a man’s neck in 1842. He did not publish his methods until 1849, several years after the use of nitrous oxide was reported by Horace Wells and the first successful public demonstration of nitrous oxide by William T.G. Morton in 1846. These pioneers set the stage for the rapid integration of anesthesia into surgical practice, which proceeded over the latter half of that century.

Shortly after World War I, with increasing popularity of office-based surgery, the utilization of a dedicated anesthesiologist in the office setting was first described by Ralph Waters in 1919. He described his experiences administering anesthesia in the surgeon’s office, where his responsibilities included supplying the operating room, recovery room, and his private doctor’s “loafing and smoking room”. He recognized the financial potential of his situation, and noted that success was intimately tied to the satisfaction of the surgeon.1

Preoperative evaluation – patient safety

The objective of anesthesia is to maintain a state of physiologic homeostasis during the stress of surgery. The physiologic response to surgery is similar to the “fight or flight” response, altering blood flow from non-vital organs to the brain and heart. In order to maintain homeostasis, preoperative determination of cardiac reserve, ability to exchange oxygen, and patient factors which may negatively impact these processes must be known. To this end, the Rule of Threes can simplify the approach to preoperative screening and focus practitioners on the aspects of the history and physical exam which influence patient outcomes in the perioperative period (Table 3.1).2 Exercise tolerance approximates cardiac reserve, and can be approximated using metabolic equivalents (METs). Several studies have demonstrated that the ability to do four or more METs correlates to improved perioperative outcomes. Walking five city blocks, climbing two flights of stairs, running over short distances, and participating in moderate recreational activity (i.e. dancing or golf) without the need to stop for rest is the equivalent of four METs.

| Acute history | 1. Exercise tolerance |

| 2. History of present illness and its treatments | |

| 3. When the patient last visited with his or her primary care physician | |

| Chronic history | 1. Medications and causes for their use and allergies |

| 2. Social history including drug, alcohol, and tobacco use and cessation | |

| 3. Family history and history of prior illnesses and operations | |

| Physical examination | 1. Airway |

| 2. Cardiovascular | |

| 3. Lung, plus those aspects specific to the patient’s condition or planned procedure |

From Miller RD. Miller’s anesthesia, 6th edn. New York: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone, 2005.

As there is no reliable classification system of preoperative risk, a standardized approach to data collection in the preoperative period can facilitate decision making throughout the patient’s course. The initial collection should happen shortly after the decision to proceed with surgery in the surgeon’s office. In addition to medical history pertinent to the specific surgical procedure, a standard set of questions designed to identify risk factors should be answered, such as those found in the Preoperative and Preprocedure Assessment Clinic (PPAC) Form.2 The physical exam should be similarly structured and standardized with some notable additions. Airway assessment is performed according to the Mallampati airway classification based on observations of oral structures visible with tongue maximally protruded, which correlates to ease of intubation (Table 3.2). Additional factors to consider which may limit airway visualization are a short neck, limited cervical spine mobility, poorly mobile or retruded mandible.

Table 3.2 Mallampati airway classification system

| I | Faucial pillars, soft palate, uvula, tonsillar pillars visualized |

| II | Faucial pillars and soft palate visualized, uvula visualized |

| III | Soft palate, base of uvula visualized |

| IV | Soft palate only |

Based on the history and physical, patients are broadly classified according to their medical fitness. The current classification system endorsed by the American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) is a modification of the Saklad classification developed in the 1940s. Useful more as a global assessment of preop status rather than a measure of risk, the ASA system classifies patients based on the presence of medical illness (Table 3.3).

Table 3.3 ASA classification system

| ASA class | Medical conditions | Common examples |

|---|---|---|

| I | Healthy, no co-existing medical illness | |

| II | Mild systemic disease with no functional limitation | Asthma, hypertension, mild obesity, diabetes (well controlled) |

| III | Severe systemic disease with functional limitation | Poorly controlled DM, stable angina, coronary artery disease |

| IV | Severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life | CHF, unstable angina |

| V | Moribund with death expected within 24 hours |

Following a focused history and physical intake, surgeons must then determine the need for additional preoperative screening tests. The tendency of surgeons is to order a large range of ancillary tests, some of which are not necessarily indicated, in an effort to have any conceivable test result available to the anesthesiologist on the morning of surgery. This poses several potential problems. Testing not indicated by medical history may lead to treatment of borderline abnormalities, which may result in patient harm and distress. In addition, since most preoperative abnormalities are not documented in the chart, the failure to investigate abnormal tests is a greater risk of medico-legal liability than the failure to detect it in the first place. Therefore, the guidelines published by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) summarized in Table 3.4 should be utilized to determine the need for additional preoperative screening tests. In addition, preoperative evaluation should include tests relevant to the type of surgery being performed. For instance, if intraoperative and postoperative bleeding is a significant risk, then a baseline hematocrit should be included in the preoperative work-up.

Table 3.4 Guidelines for preoperative screening tests (based on ASA standards)

| Preoperative test | Indicated | Not necessarily indicated |

|---|---|---|

| Electrocardiogram | Age >50 with cardiac risk factors | Age >50 with no cardiac risk factors |

| Pre-existing cardiac or peripheral vascular disease | ||

| Hypertension | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | ||

| Metabolic disease | ||

| Chest radiograph | Pre-existing cardiac or respiratory disease | Smoking, advanced age, stable cardiac disease, stable COPD, recent URI |

| COPD or reactive airway disease | ||

| Complete blood count | History of anemia | Routine use not indicated |

| Hematologic disorder | ||

| Liver disease | ||

| More invasive procedures | ||

| Coagulation studies | History of bleeding diathesis | Routine use not indicated |

| Anticoagulant therapy | Regional anesthesia (insufficient data) | |

| Liver disease | ||

| Serum chemistries | Endocrine disease | Routine use not indicated |

| Renal or liver dysfunction | ||

| Medications affecting serum/urine electrolytes | ||

| Urinalysis | Only select procedures (genitourinary procedures) | Routine use not indicated |

| Pregnancy testing | Consider in all women of childbearing age | |

| Uncertain pregnancy history |

Adapted from American Society of Anesthesiologists. Practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation: a report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation. Anesthesiology 2002;96:485–496.

Based on current practice, patient assessment by the anesthesiologist frequently occurs on the morning of surgery. While adequate for the majority of patients without significant medical co-morbidity or risk factors, there is a select group of patients with significant medical problems or preoperative risk that would benefit from an evaluation well before surgery. It is the role of the surgeon to identify these patients and ensure they receive a focused assessment by an anesthesiologist to minimize their operative risk prior to the morning of surgery (Table 3.5). Failure to do so may result in case cancellation which is frustrating for all parties involved.

Table 3.5 Indications for preoperative anesthesia evaluation prior to day of surgery (based on ASA standards)

| General | Medical condition prohibits daily activity or necessitates continual assistance |

| Hospital admission within 2 months for acute or exacerbation of chronic condition | |

| Morbid obesity (BMI >30) | |

| Cardiovascular | Angina, coronary artery disease, history of myocardial infarction |

| Symptomatic arrhythmias | |

| Poorly controlled hypertension (DBP >110, SBP >160) | |

| Congestive heart failure | |

| Respiratory | COPD or reactive airway disease requiring chronic medication |

| Recent COPD or reactive airway disease exacerbation | |

| History of airway surgery or unusual airway anatomy | |

| Endocrine | Diabetes mellitus |

| Adrenal disease | |

| Thyroid disease | |

| Hepatobiliary disease | |

| Neurological | Seizure disorder |

| CNS disease |

Adapted from American Society of Anesthesiologists. Practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation: a report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation. Anesthesiology 2002;96:485–496 and Pasternak LR. Preoperative screening for ambulatory patients. Anesthesiol Clin North America 2003;21:229–242, vii.

The specific features of each method for anesthesia will be discussed later in this chapter.

Preoperative medications

Anxiolytics

Patient anxiety is a significant consideration to address preoperatively for several reasons. The first is physiological. The anxiety associated with the anticipation of surgery, injection of local agents, and being aware of the surroundings during surgery can all have significant hemodynamic effects, which may affect the intraoperative anesthetic medications given during surgery. This potentially increases the incidence of postoperative complications, particularly nausea, vomiting, and blood pressure control. The second consideration is psychological. Anticipation of surgery often evokes psychological symptoms due to alterations in body image, previous traumatic experiences, unrealistic expectations about outcomes, and fear of pain or discomfort. A simple phone call from the surgeon or anesthesiologist on the evening prior to surgery has been shown to reduce this anxiety. Further, psychiatric disorders are not uncommon in the aesthetic population, and the risk of postoperative psychological complications (anxiety, post-traumatic stress, panic attacks) is predicted by their presence preoperatively. In this instance, premedication with an appropriate anxiolytic facilitates a more even psychological state throughout the perioperative period. Notably, in patients with pre-existing psychological disorders, anxiolytics are often continued in the postoperative period. The more common preparations of preoperative anxiolytics include oral valium taken on the morning of surgery (10–20 mg) and Versed IV/IM (2–4 mg) used immediately prior to entering the operating room.

Methods of anesthesia

General anesthesia

General anesthesia induces a state of unconsciousness and analgesia through the use of intravenous and inhaled agents, necessitating definitive airway management. It is not simply defined by the presence of an endotracheal tube. Use of general anesthesia in the ambulatory setting must be efficient and cost-effective. Although there is a higher incidence of anesthesia-related side effects when compared to other methods, general anesthesia remains the most widely utilized technique. This requires that specialized equipment, anesthesia machines, and medications are readily available in the facility.

Monitored anesthesia care

Monitored anesthesia care (MAC) is defined as the presence of an anesthesiologist to monitor vital parameters or administer supplemental drugs to patients receiving local anesthesia for surgical procedures. Up to 50% of outpatient procedures could be performed with MAC, reducing the cost of perioperative care up to 80% compared to general anesthesia. The preoperative workup for MAC should be as rigorous as general anesthesia because in a very small fraction of cases, emergent intubation may be required. In general, patients suitable for MAC are cooperative patients who understand that they may be aware during the surgical procedure. These patients should have a favorable airway and are undergoing relatively short procedures (<3 h). Contingent on these parameters is the ability of the surgeon to provide excellent local anesthesia, either via field blocks or specific nerve blockade. MAC is associated with fewer post-anesthesia side effects and more rapid recovery and discharge. The main disadvantage of MAC is lack of airway control, and requires the anesthesiologist to carefully titrate medications to maintain spontaneous respiration while keeping the patient comfortable.

Local anesthesia

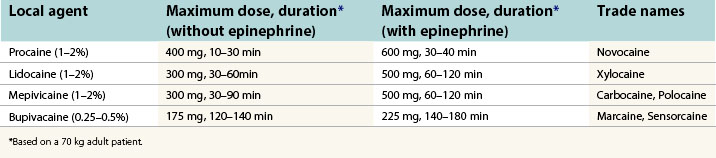

Local anesthesia is perhaps the most powerful method of anesthesia, and in skilled hands, is often the only method of anesthesia used. Local agents block nerve conduction by altering sodium conductance in neuron. Precision of placement (nerve blocks) and total dose (field blocks and infiltration) are important determinants in anesthetic effect. Central nervous system and cardiovascular toxicity are the most common serious adverse effects of local anesthetics and are directly related to dose and circulating plasma levels. The more common local agents and their clinical characteristics are listed in Table 3.6.

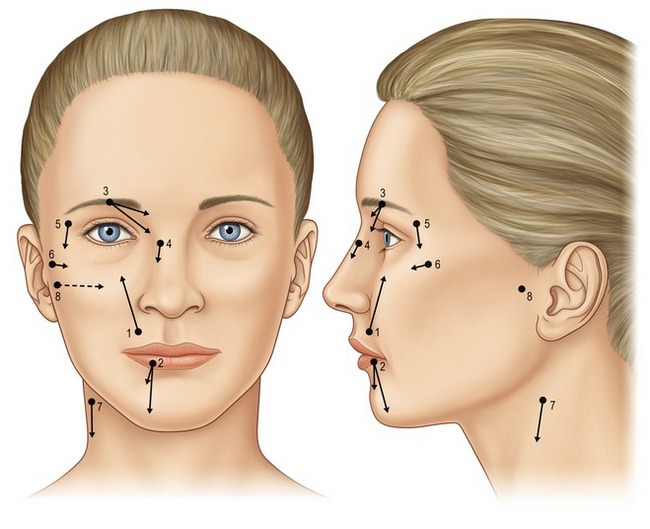

Considering the large percentage of plastic surgery procedures that involve the face, mastery of local anesthesia in the face is critical to facilitate patient comfort during a variety of office-based cases. Described eloquently by Zide in 1998,3 complete sensory blockade of the face can be accomplished using eight precisely placed regional nerve blocks (Fig. 3.1) with a minimal volume of anesthetic.

Office-based anesthesia

The concept of a surgeon operating from an office setting has been routinely practiced over several decades, but the recognition of office-based anesthesia (OBA) as a subspecialty of anesthesia is only a recent development. OBA is technically defined as the administration of anesthesia in a facility not licensed as an ambulatory surgery center, which operates and is integrated into the daily operations of a surgeon’s office. Practically speaking, there is a broad range of procedures which utilize OBA, from very minor surgical procedures, to much more invasive procedures. The level of surgical complexity that can be performed in this setting are highly dependent on the surgeon’s skill and level of comfort with the procedure. Regardless, patient selection is a critical factor in maintaining the efficiency, convenience, and cost-effectiveness of office-based procedures, and the standards of our specialty are outlined in a task force statement from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS).4 The basic clinical requirements for safe OBA can be summarized using the pneumonic POSEMED (Table 3.7).5

| Positive pressure ventilation | Small anesthesia machine or bag-mask apparatus |

| Oxygen | Gas line or cylinders |

| Suction | One unit with a backup |

| Emergency equipment | Airway supplies, defibrillator, crash cart |

| Monitors | Electrocardiogram, blood pressure, pulse oxymetry |

| Drugs | ACLS/resuscitative agents, anesthetic agents, dantrolene |

According to the ASPS, plastic surgery performed under anesthesia other than minor local with minimal oral tranquilization should be performed in a facility that is accredited by a national or state-recognized agency (such as the American Association for Accreditation of Ambulatory Surgery Facilities (AAAASF), the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (AAAHC), or the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO)), certified to participate in the Medicare program under Title XVIII, or licensed by the state the facility is located in.6 Accreditation in OBS affords several advantages to surgeons, including facility fee acquisition, regulation compliance, and a marketing advantage to patients familiar with office-based surgery. Reflecting the growing popularity of OBA, each accrediting agency has begun to tailor their criteria to smaller facilities to reduce the cost and administrative burden of accreditation.

Intraoperative considerations

Positioning

Positioning and padding the patient in the operating room is often overlooked in the busy perioperative period. Anesthetized patients lack the normal defense mechanisms from pressure-induced injury, and are at risk for nerve, vessel, joint, and skin injury. Particularly in body contouring and breast procedures where several position changes are characteristic, attention to detail in orienting and padding the patient are required. According to the ASA Closed Claims Database (1970–1995), nerve damage (16%) was second only to death (32%) in the nature of liability claims settled with ulnar neuropathy and brachial plexus injuries being the most frequent.7 As a result the ASA issued a practice advisory for the prevention of perioperative neuropathies, detailing the specific recommendations related to upper extremity, lower extremity, and padding (see summary in Miller2).

Thermoregulation

Maintenance of thermal steady state requires that dissipative heat loss is balanced by heat production. During surgery, excessive heat loss and redistribution of heat from the core to peripheral tissues contributes to mild core hypothermia. Even mild levels of hypothermia (up to 3°C) can contribute significantly to surgical outcomes, increasing morbidity of cardiac outcomes, decreased resistance to surgical wound infections, impaired coagulation, and decreased postoperative comfort. Prospective randomized studies have demonstrated that mild intraoperative hypothermia is associated with delayed wound healing, prolonged hospitalization, and a 3-fold increase in the incidence of wound infection.8

Postoperative considerations

Postoperative recovery is defined by three overlapping phases: early, immediate, and late recovery. Early recovery (phase I) describes the patient during emergence from anesthesia which begins with the discontinuation of anesthetic agents. During this phase, patients regain protective airway reflexes and motor function. Throughout early recovery, patients are assessed for criteria for discharge from the recovery room according to the Aldrete scoring system, which incorporates voluntary movement, respiration, circulation, consciousness, and oxygen saturation.9 After attaining an adequate score, patients can be moved out of the recovery room to intermediate recovery (phase II), where they are prepared for discharge. With the development of shorter acting anesthetic regimens, the concept of “fast tracking” has emerged as a cost effective means of recovery. Typically, these patients achieve an adequate Aldrete score upon entering the recovery room, and can safely be moved to phase II saving valuable recovery room resources. However, the Aldrete scoring system does not account for postoperative emesis and pain, the two main contributors to delayed discharge. As a result, White proposed a modified scoring system to determine a patient’s eligibility for fast-track status.10 Late recovery (phase III) occurs after discharge from the facility when patients return to their preoperative physiologic state.

During phase II, the evaluation of patient suitability for discharge often is passed from the anesthesiologist to the practitioners staffing the unit. Standardized criteria are used to ensure patient safety and determine home readiness, and include vital signs, ambulation, nausea and vomiting, pain, and surgical bleeding. On average, patients meet these criteria within 1–2 hours of surgery.11 The ability to tolerate oral intake is not a requirement for discharge, and patients should not be forced to drink liquids postoperatively; oral intake has not been shown to influence the incidence of nausea and vomiting. Routinely requiring patients to void postoperatively should also be avoided, unless the ability to void is an integral part of the surgical procedure.

Complications

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• The objective of anesthesia is to maintain a state of physiologic homeostasis during the stress of surgery.

• Several studies have demonstrated that the ability to do four or more metabolic equivalents (METs) correlates to improved perioperative outcomes.

• Preoperative medication management is an important concept in optimizing patient physiology before they enter the operating theater.

• While relatively hypotensive anesthesia is preferred by many surgical subspecialties, it is of particular importance in aesthetic surgery.

• Although general anesthesia remains one of the most common techniques, there is an increasing popularity of local and nerve blocks combined with intravenous sedation (monitored anesthesia care) in the ambulatory setting.

• Local anesthesia is perhaps the most powerful method of anesthesia, and in skilled hands, is often the only method of anesthesia used.

• Complete sensory blockade of the face can be accomplished using eight precisely placed regional nerve blocks with a minimal volume of anesthetic.

• The recognition of office-based anesthesia (OBA) as a subspecialty of anesthesia is a recent development.

Pitfalls

• Preoperative evaluation is to manage risk – to identify patients who are at low risk, and to reduce these risks at the time of surgery. In some cases the risk of anesthesia is equal to or greater than the surgical procedure at hand.

• Preop testing not indicated by medical history may lead to treatment of borderline abnormalities, which may result in patient harm and distress.

• There is a select group of patients with significant medical problems or preoperative risk that would benefit from an evaluation well before surgery.

• Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is a significant problem affecting approximately 30% of patients undergoing surgery with anesthesia.

• The laryngeal mask airway (LMA) does not protect the airway from aspiration, GERD, and upper airway bleeding, so its use is cautioned in patients at risk for these issues.

• Malignant hyperthermia (MH) is a potentially life-threatening complication of anesthesia that requires the availability of specific pharmacologic agents to treat a severe crisis.

1. Waters R. The downtown anesthesia clinic. Am J Surg. 1919;33(Suppl):71–73.

2. Miller RD. Miller’s anesthesia, 6th edn. New York: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone; 2005.

3. Zide BM, Swift R. How to block and tackle the face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101:840–851.

4. Iverson RE, Lynch DJ. Patient safety in office-based surgery facilities: II. Patient selection. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:1785–1790. discussion 1791–1792 –

5. Koch ME, Dayan S, Barinholtz D. Office-based anesthesia: an overview. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2003;21:417–443.

6. Iverson RE. Patient safety in office-based surgery facilities: I. Procedures in the office-based surgery setting. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:1337–1342. discussion 1343–1346 –

7. Cheney FW, Domino KB, Caplan RA, Posner KL. Nerve injury associated with anesthesia: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1062–1069.

8. Kurz A, Sessler DI, Lenhardt R. Perioperative normothermia to reduce the incidence of surgical-wound infection and shorten hospitalization. Study of Wound Infection and Temperature Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1209–1215.

9. Aldrete JA. The post-anesthesia recovery score revisited. J Clin Anesth. 1995;7:89–91.

10. White PF, Song D. New criteria for fast-tracking after outpatient anesthesia: a comparison with the modified Aldrete’s scoring system. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:1069–1072.

11. Chung F, Chan VW, Ong D. A post-anesthetic discharge scoring system for home readiness after ambulatory surgery. J Clin Anesth. 1995;7:500–506.

12. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation: a report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:485–496.

13. Pasternak LR. Preoperative screening for ambulatory patients. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2003;21:229–242. vii