20 Anesthesia for Cosmetic Procedures

Providing adequate anesthesia is an essential part of performing cosmetic procedures and successfully incorporating them into practice. In addition to offering the patient a better procedural experience, minimizing discomfort ensures greater treatment precision and may improve outcomes.1 Cosmetic treatments that commonly require anesthesia include laser treatments, such as ablative skin resurfacing, tattoo removal and hair reduction, dermal filler injections, and occasionally botulinum toxin injections.2

Four anesthesia modalities are commonly used with cosmetic procedures:

The anesthetic modality chosen is dependent on the discomfort level associated with the procedure, procedure duration, and patient tolerance for pain. Anesthesia for less painful procedures, such as botulinum toxin and laser hair reduction, can be accomplished with contact cooling using ice or a contact cooling device and topical anesthetics. More painful procedures such as dermal fillers typically require injectable anesthetics, and prolonged procedures, such as ablative laser resurfacing, often require a combination of methods such as topical anesthetic, oral analgesic, and cool air blower (see Table 20-1).

TABLE 20-1 Anesthetic Modalities Used for Cosmetic Procedures

|

Anesthetic Modalities |

Cosmetic Procedures |

|---|---|

| Injectable anesthetics | |

| Local infiltration | Dermal fillers Laser tattoo removal |

| Regional block | Dermal fillers Ablative lasers |

| Topical anesthetics | Botulinum toxin Dermal fillers Laser hair reduction Laser tattoo removal Laser photorejuvenation for pigmented lesions Ablative lasers |

| Contact cooling | Botulinum toxin Dermal fillers Laser hair reduction |

| Analgesic devices | Laser hair reduction Ablative lasers |

Injectable Anesthetics

Injectable lidocaine (1% to 2%) reduces pain by blocking neural cell membrane sodium channels and inhibiting impulse propagation. Initially, small delta nerve fibers, which are responsible for pain and temperature sensations, are blocked. Larger beta nerve fibers, which are responsible for pressure and vibration, take longer to anesthetize. For this reason, injectable anesthetics have a rapid reduction of pain but a slower reduction in sensations of pressure and pulling.3

Lidocaine may be buffered with sodium bicarbonate in a 1 : 8 or 1 : 10 ratio to reduce the burning sensation upon injection of anesthetic. See Chapter 3, Anesthesia, for information on side effects and toxicity with lidocaine and alternative options for lidocaine allergic patients.

Local Infiltration

Lidocaine with epinephrine is typically used for infiltration with cosmetic procedures because a rapid onset of anesthesia is desirable, as is the associated vasoconstriction and reduced risk of bruising associated with epinephrine. Anesthetic infiltration results in tissue edema and distortion. Care should be taken to inject the smallest possible anesthetic volumes necessary when using local infiltration for cosmetic procedures. See Chapter 3, Anesthesia for local infiltration injection techniques.

Local infiltration is commonly used to provide anesthesia for dermal filler treatments and may be used for patients who cannot tolerate laser tattoo removal. Anesthetic infiltration significantly lengthens the time of treatment, and some providers suggest that edema caused by local infiltration may reduce the efficacy of laser tattoo treatments (see Chapter 30, Tattoo Removal with Lasers).

Regional Nerve Blocks

Lidocaine without epinephrine is used for nerve blocks. Facial nerve blocks are beneficial for cosmetic procedures because anesthetic is placed outside of the treatment area. Profound anesthesia can be achieved with minimal distortion of the treatment area, which is particularly useful with dermal filler treatments.2,4 Nerve blocks are also useful for painful procedures such as ablative laser resurfacing, particularly in the sensitive perioral area.

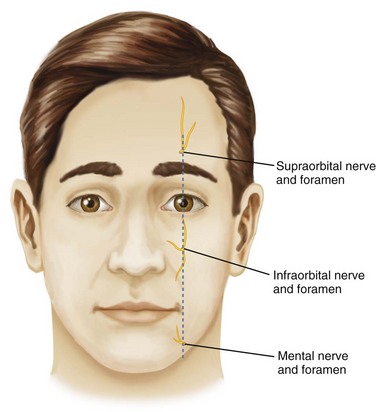

Infraorbital and mental nerve blocks are most commonly used with facial cosmetic procedures. The locations of the infraorbital and mental nerves are shown in Figure 20-1 and can be identified by palpating the nerve foramina. The infraorbital and mental nerves lie along a vertical line extending from the supraorbital notch to the mandible. The supraorbital notch lies along the upper border of the orbit and is palpable approximately 2.5 cm lateral to the midline of the face. The infraorbital foramen is palpable approximately 1 cm inferior to the infraorbital bony margin, and the mental nerve is palpable just above the margin of the mandible.

Infraorbital Nerve Block

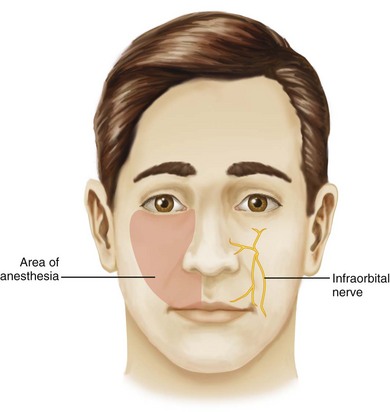

The infraorbital nerve innervates most of the upper lip, lower eyelid, lateral portion of the nose, and medial cheek. An infraorbital nerve block can anesthetize all of these regions (Figure 20-2).3 The intent of the infraorbital nerve block technique described here, utilizing a short 0.5-inch needle, is to reach the distal portions of the infraorbital nerve, not the nerve foramen, which would require a longer needle (approximately  inches long). The philtrum and the corners of the mouth are typically poorly anesthetized with infraorbital blocks, and additional local infiltration is also required when treating these areas.

inches long). The philtrum and the corners of the mouth are typically poorly anesthetized with infraorbital blocks, and additional local infiltration is also required when treating these areas.

Procedure Steps

Mental Nerve Block

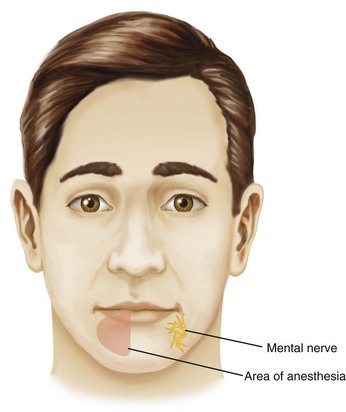

The mental nerve innervates most of the lower lip, and a mental nerve block can anesthetize this region (Figure 20-5).3 The corner of the mouth is typically poorly anesthetized, and additional local infiltration is also required when treating this area.

Procedure Steps

FIGURE 20-7 Technique for intraoral anesthetic infiltration in the corner of the mouth.

(Copyright Rebecca Small, MD.)

Patients will frequently report that their lips feel enlarged or report a sensation of drooling after infraocular and mental nerve blocks, which are good indicators of anesthetic effect. Motor nerves are also affected and patients may have slurred speech due to impaired lip function and limited pucker or smile. Patients may be reassured that these effects are temporary and once the anesthetic effect wears off they will regain sensation and motor function. See Chapter 3, Anesthesia, for additional information about nerve blocks.

Topical Anesthetics

Topical anesthetics are frequently used with cosmetic procedures due to their ease of application (see Table 20-2). They have the same mechanism of action as injectable anesthetics whereby sensory nerves are blocked by neuronal impulse inhibition.

TABLE 20-2 Commonly Used Topical Anesthetic Products for Cosmetic Proceduresa

| L-M-X | Lidocaine 4% to 5%; over-the-counter product |

| EMLA | Lidocaine 2.5% : prilocaine 2.5%; prescription |

| BLT | Benzocaine 20% : lidocaine 6% : tetracaine 4%; compounded by a pharmacy |

a See the Resources section at the end of the chapter for suppliers.

The skin is degreased with alcohol prior to application, and for ointment- and cream-based anesthetics, the product is rubbed gently into the treatment area and then occluded with plastic wrap, taking care not to occlude the nose and mouth. Figure 20-8 shows half the face treated with BLT under occlusion with plastic wrap and the other half face with Pliaglis, a self-occluding topical anesthetic. Pliaglis, temporarily removed from the market for reformulation, is applied as a thick cream and dries on exposure to air, becoming a flexible membrane that is peeled off. The face has a relatively small surface area and there are few complications with topical anesthetics. However, caution must be used with larger areas such as the extremities or the back as systemic absorption is significant, and severe complications have been reported from topical anesthetic toxicity, including death, when applied under occlusion to large skin surface areas.

The degree of anesthesia achieved with a topical anesthetic is related to the strength of the product, duration, and method of application. There are many topical anesthetics of different strengths, and it is simplest to select one product for use in the office and vary the time and method of application to suit the degree of anesthesia required for a procedure. For less painful procedures, such as laser hair reduction, topical anesthetics (e.g., BLT) can be applied for shorter duration such as 15 minutes without occlusion, whereas more painful procedures, such as tattoo removal or ablative laser resurfacing, require BLT application for 45 to 60 minutes under occlusion.5 Relative to injectable anesthetics, topical anesthetics have the disadvantage of increased visit times required for anesthesia to take effect and greater cost.

Toxicity of topical anesthetics is due to systemic absorption of the product. Several factors affect systemic absorption including the product used, surface area covered, duration of application, and the presence of an intact skin barrier. Anesthetic creams with standard formulas have better safety profiles as it is easier to predict systemic blood levels that will be obtained. For most topical anesthetic creams, systemic blood levels reached with proper use are a small fraction of the blood levels that produce toxicity. For example, 60 g of EMLA cream placed on a 400-cm2 area (equivalent to half a back) for 4 hours produces peak blood levels of lidocaine that are 1/20th the systemic toxic level of lidocaine and 1/36th the toxic level of prilocaine. This makes its application very safe, with levels well below the concentration that would cause systemic toxicity.6 Cases where topical anesthetic use has resulted in toxicity are mainly a result of patient self-application of large quantities to large surface areas or when procedures are used that disrupt the skin barrier, such as fractional laser resurfacing. Systemic lidocaine toxicity signs and symptoms range from mild dizziness to respiratory depression and correlate with serum levels.7 Higher strength topical anesthetics, such as BLT and Pliaglis, should be applied in-office for safety.8 See Chapter 3, Anesthesia for more information on topical anesthetics.

Contact Cooling

Ice or contact cooling devices are excellent modalities for achieving anesthesia, and they also improve safety with laser treatments by providing epidermal protection from thermal injury. Contact cooling may be used alone or adjunctively with the other modalities above, for laser hair reduction as well as botulinum toxin and dermal filler injections. Figure 20-9 shows a contact cooling device with adjustable temperature and a contoured tip that can be used for the face. Anesthesia is achieved by applying contact cooling immediately before treatment for approximately 1 to 3 minutes or until the skin is erythematous. The goal temperature for contact cooling is 5°C.9 Overcooling, with prolonged blanching of the skin, can result in epidermal injury.

Analgesic Devices

Analgesic devices can be used with laser treatments to reduce patient discomfort and to reduce the risk of complications from thermal injury. Many lasers have built-in cooling mechanisms. Those that do not have built-in cooling mechanisms can use external analgesic devices such as cool air blowers or pneumatic skin flattening. Cool air blowers force air through a hose that is directed over the treatment area to achieve a goal skin temperature of 20°C.10 (Figure 20-10 shows an example of a forced air cooling device, the ArTek Air by ThermoTek.) This noncontact method of cooling is particularly useful with ablative laser treatments.

FIGURE 20-10 Air cooling device (ArTek Air by ThermoTek).

(Courtesy of ThermoTek, Flower Mound, Texas.)

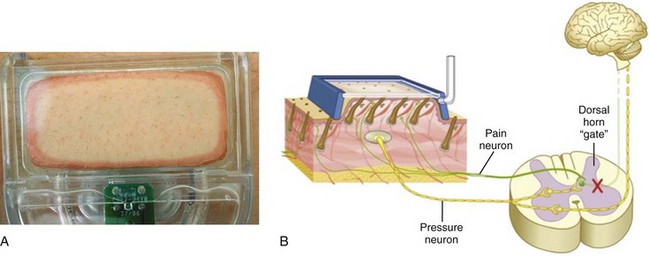

Pneumatic skin flattening utilizes negative pressure to elevate and flatten skin against the device window (Figure 20-11A). The mechanism of action of these devices is based on the gate theory of pain, whereby the pressure generated by the pneumatic device inhibits pain sensation through overwhelming and blocking the pain pathways (Figure 20-11B). Some laser devices have pneumatic skin flattening incorporated into the laser and others have a separate pneumatic device that is attached to the treatment tip (Figure 20-12).11 The disadvantages of assistive external cooling devices are the additional use of space, cost of the device, and for air blowers, an occasional requirement for an assistant and risk of overcooling if the device remains stationary in one spot on the skin.

1. Small R. Aesthetic procedures introduction. In: Mayeaux E, editor. The Essential Guide to Primary Care Procedures. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:195-199.

2. Small R. Dermal fillers for facial rejuvenation. In: Mayeaux E, editor. The Essential Guide to Primary Care Procedures. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:214-233.

3. Foley K, Pianalto D. Facial anesthesia. Emerg Med. 2005:30-34.

4. Salam GA. Regional anesthesia for office procedures: part I. Head and neck surgeries 4. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69(3):585-590.

5. Lee MS. Topical triple-anesthetic gel compared with 3 topical anesthetics. Cosmetic Dermatol. 2003;26(61):35-38.

6. Kaweski S. Topical anesthetic creams. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(6):2161-2165.

7. Marra DE, Yip D, Fincher EF, et al. Systemic toxicity from topically applied lidocaine in conjunction with fractional photothermolysis. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142(8):1024-1026.

8. Achar S. Topical anesthetic complications. In: Pfenninger JL, Fowler GC, editors. Pfenninger and Fowler’s Procedures for Primary Care. Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier, 2010.

9. Altschuler GB, Zenzie HH, Erofeev AV, et al. Contact cooling of the skin. Phys Med Biol. 1999;44:1003-1023.

10. Raulin C, Greve B, Hammes S. Cold air in laser therapy. Lasers Surg Med. 2000;27:404-410.

11. Lask G, Friedman D, Eman M, et al. Pneumatic skin flattening (PSF): a novel technology for marked pain reduction in hair removal with high energy density lasers and IPLs. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2006;8(2):76-81.

Achar S, Chan J. Topical anesthesia. In Pfenninger JL, Fowler GC, editors: Pfenninger and Fowler’s Procedures for Primary Care, 3rd ed, Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier, 2010.

Amundsen GA. Local anesthesia. In Pfenninger JL, Fowler GC, editors: Pfenninger and Fowler’s Procedures for Primary Care, 3rd ed, Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier, 2010.

Khodaee M, Kelly BF. Peripheral nerve blocks. In Pfenninger JL, Fowler GC, editors: Pfenninger and Fowler’s Procedures for Primary Care, 3rd ed, Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier, 2010.

McDaniel WL, Jarris R. Local and topical anesthesia. In Pfenninger JL, Fowler GC, editors: Pfenninger and Fowler’s Procedures for Primary Care, 3rd ed, Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier, 2010.

Skoczlas L. Oral/facial anesthesia. In Pfenninger JL, Fowler GC, editors: Pfenninger and Fowler’s Procedures for Primary Care, 3rd ed, Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier, 2010.

Small R, Hoang D. Anesthesia. In: Small R, Hoang D, editors. A Practical Guide to Dermal Filler Procedures. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011.

Small R, Zimmerman EM. Anesthesia. In: Small R, Zimmerman EM, editors. A Practical Guide to Cosmetic Lasers. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012.