3 Anesthesia

Topical Anesthetics

Common anesthetics include the following:

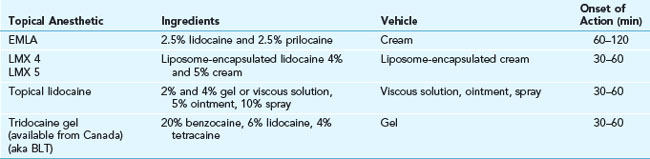

Table 3-1 shows the onset of action for the most commonly used topical anesthetics in skin procedures. EMLA (eutectic mixture of local anesthetics) cream consists of 2.5% lidocaine and 2.5% prilocaine in an oil-in-water emulsion. This anesthetic cream works best if applied for 30 minutes under occlusion or 60 minutes without occlusion before anesthesia is needed. It can be useful in treating children or a patient of any age who is afraid of needles. EMLA cream is used for some laser procedures, superficial light electrodesiccation of benign growths, and curettage of molluscum contagiosum. In Figure 3-1B the EMLA has been applied to the lower eyelids before electrodesiccation of syringomas. EMLA is available in 5-g tubes with occlusive dressings or in 30-g tubes without dressings. EMLA should not be used in infants younger than 3 months because the metabolites of prilocaine form methemoglobin. In one randomized control trial, EMLA and LMX 4 provided comparable levels of anesthesia after a single 30-minute application under occlusion prior to electrodesiccation of dermatosis papulosa nigra.1

Topical Refrigerants/Cryoanesthesia

Liquid nitrogen can freeze the skin to cause a numbing effect; however, its use causes immediate pain and little real anesthesia. Rather than using liquid nitrogen for local anesthesia for skin tag excision, it is easier and less painful to use the liquid nitrogen with a Cryo Tweezer to treat the skin tags directly (see Chapter 15, Cryosurgery). Also, liquid nitrogen can be sprayed or directly applied to skin tags or molluscum rather than using it as anesthesia. This also avoids the need to deal with blood and hemostasis issues.

Contact cooling devices and assistive external devices are frequently used in laser treatments and are covered in Chapter 20, Anesthesia for Cosmetic Procedures.

Local Anesthesia by Injection

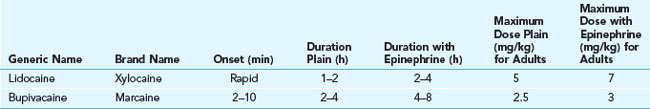

Lidocaine is the most widely used local anesthetic for injection in skin surgery. Bupivacaine (Marcaine) is used occasionally when long-lasting anesthesia is desired. Lidocaine has the advantage of having a more rapid onset (within 1 minute) and shorter duration of anesthesia than bupivacaine. This shorter duration is sufficient and preferable for most skin surgery. When lidocaine is mixed with epinephrine, it lasts almost as long as bupivacaine and hurts less.2 See Table 3-2 for a comparison of amide local anesthetics.

1% Lidocaine with Epinephrine

For most skin surgery procedures, the recommended anesthetic is 1% lidocaine with epinephrine. Its advantages include almost immediate anesthesia, adequate duration of anesthesia, and decreased bleeding because of the epinephrine. The incidence of true allergies is negligible. Lidocaine without epinephrine has a duration of 1.5 to 2 hours, whereas lidocaine with epinephrine has a duration of 2 to 6 hours.3 The most common commercial preparation contains 1% lidocaine (10 mg/mL) with 1 : 100,000 of epinephrine. In a study that measured the effect of subdermal injection of lidocaine combined with epinephrine on cutaneous blood flow, laser Doppler imaging demonstrated an immediate decrease in cutaneous blood flow, which was maximal at 10 minutes in the forearm and 8 minutes in the face.4

Note that the initial skin blanching with injection is due to hydrostatic pressure along with the effect of epinephrine. When hemostasis is critical to the procedure, it is best to wait 8 to 10 minutes for the epinephrine to produce maximal vasoconstriction. Waiting is less important for shave biopsies of lesions that are not very vascular in patients who are not anticoagulated (Figure 3-2). Injecting enough anesthetic so that the skin is firm can limit the amount of bleeding because small blood vessels become compressed by the anesthetic fluid (Figure 3-3).

Maximal Doses

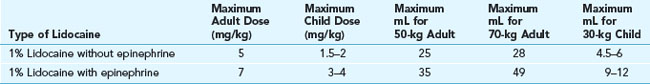

Maximal safe doses of 1% lidocaine with or without epinephrine are found in Table 3-3. Above these doses the risk of neurotoxicity and seizures is increased. In most adults (over 50 kg) up to 35 mL of 1% lidocaine with epinephrine is safe. Use of 1% lidocaine is preferable to 2% in most cases because a larger volume of anesthesia produces greater hemostasis and makes most cutaneous surgery easier to perform. Two percent lidocaine without epinephrine is useful in various nerve blocks including digital blocks when less volume is needed. Some clinicians prefer 2% lidocaine with epinephrine when they want to avoid tissue distortion from too much anesthetic volume. In this case, toxicity is not an issue because less than 5 mL of anesthesia are being used.

Decreasing the Pain of Local Anesthesia

Techniques to decrease the pain caused by injection of local anesthesia include the following:

The main technique for decreasing the pain of injection is to inject the local anesthetic very slowly using a small-gauge needle (27 or 30 gauge). The larger the gauge number, the smaller the needle diameter and the less painful the injection. Use 30-gauge needles on the most sensitive areas including the face, the ears, the fingers, and the genitals. When injecting anesthesia for a laceration repair, injecting from within a laceration is less painful than injecting into intact skin.5

Adding sodium bicarbonate (8.4% for injection) in a 1 : 10 dilution to the lidocaine and epinephrine anesthetic solution markedly decreases the pain caused by injection (e.g., 1 mL of sodium bicarbonate can be added to 9 mL of lidocaine). The addition of sodium bicarbonate neutralizes the commercially available lidocaine-epinephrine solutions that have a pH of 4 to 6. Although this takes more time, your patients will appreciate that the injection is less painful. The lidocaine-bicarbonate syringes need to be made at the time of use or may be kept for 1 week at room temperature and up to 2 weeks with refrigeration.6 In our office we make the following syringes each morning:

A warm (40°C) and neutral (pH 7.35) anesthetic preparation has been found to be less painful on injection than room-temperature nonneutral preparations.7–9 One study suggests that warming and buffering have a synergistic effect.8 Skin infiltration with warm buffered lidocaine was significantly less painful than infiltration with room-temperature unbuffered lidocaine, warm lidocaine, or buffered lidocaine.8 In another study, the mean pain scores for the four solutions were 44.2 for plain lidocaine, 42.2 for warmed lidocaine, 36.7 for buffered lidocaine, and 29.2 for warmed buffered lidocaine (lower numbers equal less pain).9 In one study, to reduce the pain of lidocaine infiltration, buffering was more effective than warming (warming was only to 38.9°C).10

Injection Technique

For shave and punch biopsies, the tip of the needle should reach the deep dermis so that an elevation and blanching of the tissue occurs (Figures 3-2 and 3-3). If the anesthetic is injected too deep into the subcutaneous tissue, no elevation will occur. When an injection is superficial in the dermis, you may see an accentuation of the follicles called peau d’orange. This skin distention is more painful than the pain that occurs with a deeper dermis injection. However, if you intend to do a shave biopsy, you can start with a deeper dermis injection and finish with a more superficial injection to raise the lesion for biopsy. Starting deeper and adjusting the needle to a more superficial level is an effective technique (this can be done without removing the needle from the original injection site).

Adverse Reactions

For patients with normal circulation, it is safe to use epinephrine for local anesthesia in areas such as the tip of the nose, the fingers and toes, the ears, or the penis despite old dogma that epinephrine should not be used in these areas (Figure 3-4). However, epinephrine is generally not recommended for digital ring blocks, full ring blocks around the ear, penile nerve blocks, and other regional or field blocks in these areas. Furthermore, epinephrine should not be used in the very distal extremities of a patient with poor circulation such as patients with peripheral vascular disease or Raynaud’s phenomenon.

A number of studies have even provided evidence to dispute the dogma that using epinephrine in a digital block produces digital necrosis.11–13 Proper injection technique and adequate selection of patients (absence of thrombotic, vasospastic conditions, or uncontrolled hypertension) are mandatory to minimize complications. The addition of epinephrine, in fact, reduced the need for the use of tourniquets and large volumes of anesthetic and provided better and longer pain control during digital procedures.11–13 We still choose to use 2% lidocaine without epinephrine for digital blocks but do use epinephrine in wing blocks when a matrix biopsy is planned (see Chapter 18, Nail Procedures).

Rare adverse effects associated with too large a systemic dose of injectable anesthetics (injection into a vein or too large a dose of the anesthetic) include myocardial depression and CNS effects such as light-headedness, tinnitus, perioral tingling, metallic taste, tremors, slurred speech, and seizures.1

Nerve Blocks

Digital blocks and regional blocks are examples of nerve blocks (see Boxes 3-1 to 3-5). The advantages of a nerve block are that it provides a longer duration of anesthesia and does not distort the anatomic landmarks.

BOX 3-1

Nerve Blocks

Source: Adapted from Vidimos A, Ammirati C, Pobleti-Lopez C. Dermatologic Surgery. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009.

BOX 3-2

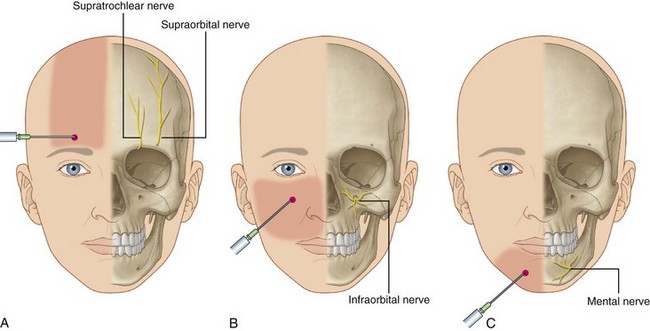

Supraorbital/Supratrochlear Nerve Block (V1)

Provides sensation to forehead.

Source: Adapted from Vidimos A, Ammirati C, Pobleti-Lopez C. Dermatologic Surgery. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009.

BOX 3-3

Infraorbital Block (V2)

Provides sensation to lower eyelid, medial cheek, nose, and upper lip.

BOX 3-4

Mental Nerve Block (V3)

Sensation to lower lip, chin, and mucous membranes.

Source: Adapted from Vidimos A, Ammirati C, Pobleti-Lopez C. Dermatologic Surgery. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009.

BOX 3-5

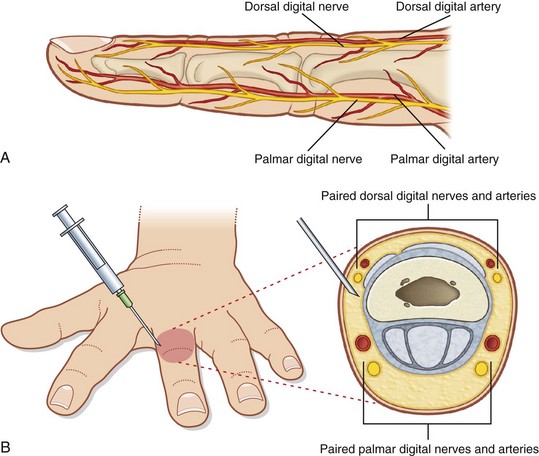

Digital Block

Paired dorsal and medial digital nerves.

Source: Adapted from Vidimos A, Ammirati C, Pobleti-Lopez C. Dermatologic Surgery. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009.

The digital block can be more effective than a local injection on the digit especially for surgery around the nail. Anesthetizing the digital nerves with lidocaine will almost always provide good anesthesia. Injection on each side of the digit with lidocaine will anesthetize both dorsal and ventral nerves on either side of the digit (Figure 3-5). A 3- to 5-mL syringe may be used with 1% or 2% lidocaine, delivering 1.0 to 1.5 mL on each side of the digit and 1.0 mL on the top (Figure 3-6).

A wing block is an alterative for surgery on any part of the nail unit (Figure 3-7). The main advantage over a digital block is that it provides better hemostasis at the site of surgery regardless of whether or not epinephrine is used. Some clinicians will use half-strength epinephrine by mixing 2% lidocaine with 1% lidocaine with epinephrine in a 1 : 1 solution. Wing blocks work faster than a digital block, but the injection usually hurts more at first. A wing block can be performed after a digital block to help with hemostasis and to ensure excellent anesthesia (see Chapter 18, Nail Procedures).

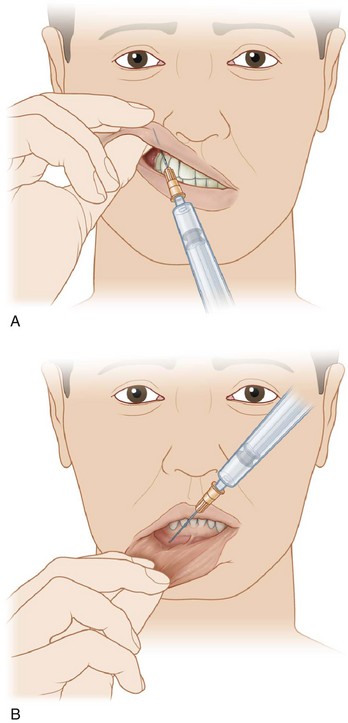

Regional blocks (i.e., infraorbital, supraorbital, or mental nerve blocks) are helpful when a larger area of the face is to be anesthetized and anatomic distortion is to be avoided. For that reason, facial regional blocks are very helpful for cosmetic procedures involving fillers and ablative lasers. These blocks can be done with a small amount of 1% or 2% lidocaine (0.5 to 1.0 mL) without epinephrine. See Figure 3-8 for a guide on where to inject for these blocks. The clinician should be aware that these blocks do not assist in hemostasis so some lidocaine with epinephrine may still be useful at the local area as an adjunct to the regional block. Regional blocks can be done through the skin as in Figure 3-8 or using an intraoral approach as in Figure 3-9. Oral surgeons regularly use the intraoral approach (Figure 3-10). See Chapter 20, Anesthesia for Cosmetic Procedures, for more additional information on these blocks.

FIGURE 3-9 Intraoral route for blocking infraorbital and mental nerves.

(From Robinson J, Hanke CW, Siegel D, Fratila A. Surgery of the Skin. London: Mosby; 2010.)

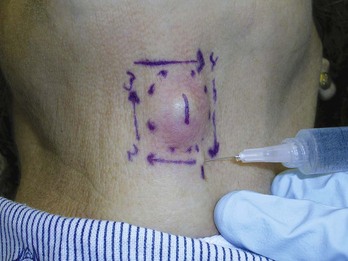

Field or Ring Block

A field block creates a “wall” of anesthesia around an area to be anesthetized. Rather than injecting the anesthetic directly into the area to be numbed, the anesthetic is injected around it to affect the nerves that normally transmit sensations of pain and touch (Figure 3-11). A field block is useful when it is necessary to avoid distorting the tissue to be cut, in cases of infection, and in locations where local anesthesia may not work adequately. Epinephrine is used with lidocaine to decrease bleeding.

The ring block is especially useful before draining an abscess or removing a deep epidermal cyst. The acid environment of the abscess can hydrolyze the anesthetic. The field block allows the anesthetic to work on normal surrounding tissue and avoids the problem of distending the abscess further by keeping the anesthetic out of the abscess cavity. A 27-gauge,  -inch needle is useful for administering a field block. In Figure 3-11, the ring block injections are marked on the skin. Each subsequent injection goes into an area that was previously anesthetized. This method also minimizes the chance that you will be sprayed by the contents of a distended abscess or cyst.

-inch needle is useful for administering a field block. In Figure 3-11, the ring block injections are marked on the skin. Each subsequent injection goes into an area that was previously anesthetized. This method also minimizes the chance that you will be sprayed by the contents of a distended abscess or cyst.

Pregnancy and Lactation

Local anesthetics can cross the placental membrane by passive diffusion. Shave and punch biopsies involve such a small amount of local anesthetic that there is little risk to the fetus. Lidocaine is pregnancy category B and epinephrine is pregnancy category C. Epinephrine should be used conservatively, because large doses can cause decreased placental perfusion. Elective and large procedures are best delayed until after delivery.14

Lidocaine and epinephrine are excreted in breast milk and should be used with caution in women who are nursing. If a procedure with local anesthesia is needed, the woman may pump her breast milk several hours after the procedure and discard the expressed milk.14

Summary of Materials

See Chapter 2 for a list of distributors of surgical and anesthetic supplies.

1. Carter EL, Coppola CA, Barsanti FA. A randomized, double-blind comparison of two topical anesthetic formulations prior to electrodesiccation of dermatosis papulosa nigra. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1-6.

2. Howe NR, Williams JM. Pain of injection and duration of anesthesia for intradermal infiltration of lidocaine, bupivacaine, and etidocaine. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1994;20:459-464.

3. Achar S, Kundu S. Principles of office anesthesia: part I. Infiltrative anesthesia. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66:91-94.

4. Ghali S, Knox KR, Verbesey J, et al. Effects of lidocaine and epinephrine on cutaneous blood flow. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61:1226-1231.

5. Bartfield JM, Sokaris SJ, Raccio-Robak N. Local anesthesia for lacerations: pain of infiltration inside vs outside the wound. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5:100-104.

6. Bartfield JM, Homer PJ, Ford DT, Sternklar P. Buffered lidocaine as a local anesthetic: an investigation of shelf life. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:16-19.

7. Yang CH, Hsu HC, Shen SC, et al. Warm and neutral tumescent anesthetic solutions are essential factors for a less painful injection. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1119-1122.

8. Mader TJ, Playe SJ, Garb JL. Reducing the pain of local anesthetic infiltration: warming and buffering have a synergistic effect. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:550-554.

9. Colaric KB, Overton DT, Moore K. Pain reduction in lidocaine administration through buffering and warming. Am J Emerg Med. 1998;16:353-356.

10. Bartfield JM, Crisafulli KM, Raccio-Robak N, Salluzzo RF. The effects of warming and buffering on pain of infiltration of lidocaine. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:254-258.

11. Krunic AL, Wang LC, Soltani K, et al. Digital anesthesia with epinephrine: an old myth revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:755-759.

12. Thomson CJ, Lalonde DH, Denkler KA, Feicht AJ. A critical look at the evidence for and against elective epinephrine use in the finger. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:260-266.

13. Lalonde D, Bell M, Benoit P, et al. A multicenter prospective study of 3,110 consecutive cases of elective epinephrine use in the fingers and hand: the Dalhousie Project clinical phase. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2005;30:1061-1067.

14. Vidimos A, Ammirati C, Pobleti-Lopez C. Dermatologic Surgery. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009.

-inch needle.

-inch needle. -inch needle (27 or 30 gauge).

-inch needle (27 or 30 gauge). -inch needle.

-inch needle.