Intrathoracic and extrathoracic

A Breast biopsy

Breast cancer is diagnosed by excisional breast biopsy (by needle aspiration or open excision) followed later by a more definitive surgical procedure designed to decrease tumor bulk and thus enhance the effectiveness of systemic therapy (chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, or radiation). Carcinoma of the breast is an uncontrolled growth of anaplastic cells. Types include ductal, lobular, and nipple adenocarcinomas.

2. Preoperative assessment and patient preparation

a) History and physical examination

(1) The most common initial sign of carcinoma of the breast is a painless mass.

(2) Bloody discharge is more indicative of cancer than is spontaneous unilateral serous nipple discharge.

(3) Signs of advanced breast cancer include dimpling of skin, nipple retraction, change in breast contour, edema, and erythema of the breast skin.

B Bronchoscopy

Bronchoscopy permits direct inspection of the larynx, trachea, and bronchi. Indications include collection of secretions for cytologic or bacteriologic examination, tissue biopsy, location of bleeding and tumors, removal of a foreign body, and implantation of radioactive gold seeds for tumor treatment. A common indication for bronchoscopy is suspicion of bronchial neoplasm.

a) History and physical examination

(1) Respiratory: Evaluate for chronic lung disease, wheezing, atelectasis, hemoptysis, cough, unresolved pneumonia, diffuse lung disease, and smoking history.

(2) Cardiac: Question underlying dysrhythmias because they may arise with stimulation from the scope or could be a sign of hypoxemia during the procedure.

(3) Gastrointestinal: Assess the patient’s drinking history and nutritional intake.

(3) Pulmonary function test with lung disease

(4) Laboratory tests, including a complete blood count, electrolytes, glucose, and others as indicated by the patient’s medical condition

c) Preoperative medications and intravenous (IV) therapy

(1) The patient may already be taking sympathomimetic bronchodilators and aminophylline. The patient may benefit from administration of an inhaled bronchodilator preoperatively.

(2) Sedatives and narcotics are to be used with caution in patients with poor respiratory reserve.

(3) Cholinergic blocking agents reduce secretions.

(4) IV lidocaine, 0.5 to 1.5 mg/kg, decreases airway reflexes.

(5) Topical anesthesia involves 4% lidocaine using a nebulizer to anesthetize the airway by spraying the palate, pharynx, larynx, vocal cords, and trachea.

(6) One 18-gauge peripheral IV line with minimal fluid replacement is used.

a) Monitoring equipment is standard: An arterial line is used if thoracotomy is planned or the patient is unstable.

b) Pharmacologic agents: Lidocaine and cardiac drugs are used.

c) Position: Supine; the table may be turned. One must manage an upper airway that is shared with the surgeon.

a) Local infiltration or general anesthesia is used.

b) The technique of choice is general anesthesia. One must discuss with the surgeon whether a rigid or flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy will be performed (see the box on pg. 350).

(1) Transtracheal: 2 mL of 2% plain lidocaine through the cricothyroid membrane using a 22-gauge needle attached to a small syringe

(2) Superior laryngeal: 25-gauge needle anterior to the superior cornu of the thyroid cartilage

d) If topical anesthesia is used, consider total dosage of local anesthetic and be prepared to treat local anesthetic toxicity.

(a) The endotracheal tube (ETT) must be large enough (8–8.5 mm) to permit the endoscope to pass easily.

(b) Do not administer oxygen through the suction channel of the flexible bronchoscope (to avoid gas trapping and inducing barotrauma).

(i) Ventilation through the side port requires high gas flow rates and an intact glass eyepiece.

(ii) Suction, biopsy, and foreign body manipulation require removal of the glass and loss of ventilation.

(i) Give patients high fraction of inspired oxygen and hyperventilate them before apneic oxygenation.

(ii) Perform jet ventilation through the side port of a catheter alongside the bronchoscope.

(iii) Place the tracheal tube to the left side of the mouth because the surgeon will insert the scope down the right side.

(iv) The ETT must be smaller in diameter to allow surgical access.

(v) Consider total IV anesthesia when using jet ventilation.

(3) After preoxygenation, general anesthesia is induced with the insertion of an oral ETT.

(4) Succinylcholine may be contraindicated if the patient has severe muscle spasm, wasting, or complains of myalgia.

(1) General anesthesia must provide good muscle relaxation without patient movement such as coughing, laryngospasm, or bronchospasm. Because of the extensive sensory innervation in the trachea and bronchi, a deep plane of anesthesia must be maintained to avoid coughing, bucking, and exaggerated hemodynamic response.

(2) Cardiac dysrhythmia (i.e., supraventricular tachyarrhythmias, premature ventricular contraction, and atrial dysrhythmias) may be a problem. Plan appropriate treatment modalities.

(3) Inhalation anesthetics are useful to provide adequate suppression of upper airway reflexes and permit high inhaled concentrations of oxygen.

(4) Air leaks around the bronchoscope may be minimized by having an assistant externally compress the patient’s hypopharynx.

(5) Spontaneous ventilation is preferred in cases of foreign body removal; positive airway pressure could push the foreign body deeper into the bronchial tree.

a) If nerve blocks are administered, keep the patient from eating or drinking for several hours postoperatively; the blocks cause depression of airway reflexes.

b) Subglottic edema may be treated with aerosolized racemic epinephrine 2.25% (0.05 mL/kg) and IV dexamethasone (0.1 mg/kg).

c) Chest radiographs are obtained to detect atelectasis or pneumothorax.

d) Complications: A toxic reaction to local anesthetic is possible.

C Bullae

Bullae are air-filled spaces of lung tissue resulting from the destruction of alveolar tissues and consolidation of alveoli into large pockets. They offer low resistance to inspiration and tend to increase in size with positive pressure ventilation. A valvelike mechanism may be present that causes air trapping on expiration. Enlarging bullae compress normal lung tissue and vasculature to the point of causing hypoxemia, polycythemia, and cor pulmonale. Overdistended bullae can rupture and cause pneumothorax or tension pneumothorax with cardiopulmonary collapse, requiring insertion of a chest tube. A chest tube may show a large, continuous air leak, and ventilation may be difficult.

a) A double-lumen tube (DLT) is indicated when a thoracotomy is planned to resect bullous tissue. This allows for separate ventilation of each lung and the ability to use adequate tidal volumes (Vts) on the healthy lung without risking further rupture of bullae.

b) In the event of a pneumothorax, the unaffected lung can be ventilated while a chest tube is placed or the incision is made. When the surgery is nearing completion, each lung can be separately checked for air leaks.

c) During general anesthesia for bullous disease, spontaneous ventilation is desirable until the chest is opened to reduce the risk of rupture of bullae. Patients with severe cardiopulmonary disease may not be able to ventilate adequately under general anesthesia, and positive-pressure ventilation may be required.

d) Small Vts, high respiratory rates, and high Fio2 can be delivered by gentle manual ventilation to keep airway pressures below 10 to 20 cm H2O.

e) An alternative to positive-pressure ventilation is high-frequency jet ventilation, which is used to decrease the chance of barotrauma.

f) Nitrous oxide should be avoided in bullous disease because it rapidly enlarges the air-filled spaces.

g) The choice of other anesthetic agents depends on the patient’s cardiopulmonary status and the anesthesia provider’s desire to maintain spontaneous ventilation.

h) After excision of the bullae, normal lung tissue rapidly expands, and compliance and gas exchange rapidly improve. Care must still be taken with positive-pressure ventilation if some unresectable bullae remain.

D Mastectomy

Total mastectomy (simple or complete mastectomy) removes only the breast; no axillary node dissection is involved. It is used for the treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ. Radical mastectomy involves removal of the breast, underlying pectoral muscles, and axillary lymph nodes. There are two major alternatives to radical mastectomy: modified radical mastectomy and wide local excision of the tumor (partial mastectomy or lumpectomy) with axillary dissection. This treatment is followed by postoperative radiation therapy to the remaining breast.

Patients often have no other underlying medical problems. The anesthetic implications of metastatic spread to bone, brain, liver, lung, and other areas should be considered. Preoperative assessment should be routine, with special consideration to the following:

a) Cardiac: Cardiomyopathies may result from chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin (>550 mg/m2). Patients exposed to this type of drug may experience cardiac dysfunction, and a cardiac consultation may be needed to determine ventricular function.

b) Respiratory: If the patient has undergone radiation therapy, there may be some respiratory compromise. Drugs such as bleomycin (>200 mg/m2) can cause pulmonary toxicity and necessitate administration of a low fractional of inspired oxygen (<0.30). However, a higher fraction of inspired oxygen is warranted if necessary to keep SpO2 at 88% to 92% or greater.

c) Neurologic: Breast cancer often metastasizes to the central nervous system, and there could be signs of focal neurologic deficits, altered mental status, or increased intracranial pressure. If mental status is altered, a full medical workup should be undertaken without delay. Surgery should be postponed until the cause is found.

d) Hematologic: The patient may be anemic secondary to chronic disease or chemotherapeutic agents.

Monitors and equipment are standard. If the procedure is for a superficial biopsy, monitored anesthesia care with sedation can be used. Be sure to place the blood pressure cuff on the arm opposite the operative site. The patient is placed in the supine position during the procedure.

4. Perioperative management and anesthetic technique

a) Routine induction and maintenance are used.

b) Pressure dressings are often applied with the patient anesthetized and “sitting up” at the conclusion of the procedure. Communicate with the surgeon if this type of dressing will be used to time emergence more appropriately. If there are no further considerations, the patient may be extubated in the operating room.

a) If the patient is unstable hemodynamically (which may suggest a tension pneumothorax), place a 14-gauge angiocatheter in the second intercostal space while the surgeons prepare for chest tube placement.

b) Postoperative chest radiography may be needed if a pneumothorax is suspected.

(1) Deep surgical exploration may inadvertently cause a pneumothorax. The patient should be monitored for signs and symptoms of pneumothorax, which include increased peak inspiratory pressures, decreased arterial carbon dioxide pressure, asymmetric breath sounds, hemodynamic instability, and hyperresonance to percussion over the affected side.

(2) Diagnosis is concluded by chest radiography.

(3) Treatment includes placing the patient on a fractional inspired oxygen of 100% and insertion of a chest tube.

E Mediastinal masses

Masses in the mediastinum can compress vital structures and cause changes in cardiac output, obstruction to air flow, atelectasis, or central nervous system changes. Masses can include benign or cancerous tumors, thymomas, substernal thyroid masses, vascular aneurysms, lymphomas, and neuromas. Surgical procedures for diagnosis or treatment of these masses may include thoracotomy, thoracoscopy, and mediastinoscopy.

Tumors within the anterior mediastinum can cause compression of the trachea or bronchi, increasing resistance to air flow. Changes in airway dynamics with supine positioning, induction of anesthesia, and positive-pressure ventilation can cause collapse of the airway with total obstruction to flow. Manipulation of tissue intraoperatively, edema, and bleeding into masses can increase their size and effects on airways or vasculature. As a result, total airway obstruction can occur at any phase of anesthesia, including during positioning, induction, intubation, emergence, or recovery. Positive pressure ventilation may be impossible even with a properly placed ETT if the mass encroaches on the airway distal to the ETT. Localization of the mass by computed tomography (CT) or bronchoscopy may facilitate placement of the ETT distal to the mass. Maintenance of spontaneous ventilation retains normal airway-distending pressure gradients and can maintain airway patency when positive pressure will not. Maintenance of spontaneous ventilation is the goal when managing these patients.

Signs and symptoms of respiratory tract compression should be sought preoperatively. Many patients with mediastinal masses are asymptomatic or characterized by vague signs such as dyspnea, cough, hoarseness, or chest pain. The common symptoms are listed in the following box.

a) Wheezing may represent air flow past a mechanical obstruction rather than bronchospasm.

b) Shortness of breath at rest or with exertion and coughing are other symptoms. Symptoms may be positional, worsening in the supine or other position.

c) A chest radiograph may show airway compression or deviation.

d) CT, transesophageal echocardiography, and magnetic resonance imaging may further delineate the size and effects of masses.

e) Subclinical airway obstruction may be revealed by flow-volume loops, which demonstrate changes in flow rates at different lung volumes.

f) Decreased maximal inspiratory or expiratory flow rate alerts the anesthesia provider to increased risk of obstruction perioperatively.

g) Comparison of flow rates obtained with the patient in the upright and supine positions can reveal whether the supine position will exacerbate obstruction intraoperatively.

h) If any sign of respiratory obstruction is present, surgery for the biopsy of masses should be performed with the patient under local anesthesia whenever possible.

i) Radiation to decrease mass bulk in radiosensitive tumors is recommended before surgery to reduce the risk of airway obstruction.

a) In the case of mediastinal masses, awake fiberoptic bronchoscopy and intubation enable the anesthesia provider to evaluate the large airways for obstruction and to place the ETT beyond the obstruction while maintaining spontaneous ventilation.

b) The effect of positional changes can be checked with the bronchoscope. Spontaneous ventilation should be maintained as long as possible or throughout the procedure if feasible.

c) The ability to effectively provide positive-pressure ventilation should be proven before administration of muscle relaxants.

d) The use of a helium–O2 mixture can improve air flow during partial obstruction. The use of this low-density gas decreases turbulence past a stenotic area, improving flow and decreasing the work of breathing.

e) Emergency strategies that may become necessary in the case of airway compromise include repositioning or awakening the patient, rigid bronchoscopy to establish a patent airway beyond the obstruction, or (in the case of life-threatening compromise), sternotomy with manual decompression of the mass off of the airway.

f) Mediastinal masses can cause compression of great vessels or cardiac chambers. Compression of the pulmonary artery is rare because it is a higher pressure vessel than the pulmonary vein and is somewhat protected by the arch of the aorta. Compression of this vessel, however, can lead to sudden hypoxemia, hypotension, or cardiac arrest. Patients with any cardiac or great vessel involvement should receive only local anesthesia whenever possible, remain in the sitting position, and maintain spontaneous respirations. If general anesthesia is required, prior establishment of the means for extracorporeal ventilation should be established.

g) Superior vena cava syndrome is venous engorgement of the upper body caused by compression of the superior vena cava by a mass. It leads to the following signs and symptoms: dilation of collateral veins of the upper part of the thorax and neck; edema and rubor of the face, neck, and upper torso and airway; edema of the conjunctiva with or without proptosis; shortness of breath; headache; visual distortion; or altered mentation. Placement of IV lines in the lower extremities is preferred because insertion in sites above the superior vena cava could delay the drug effect as a result of slow distribution. Fluids should be administered with caution because large volumes can worsen symptoms.

F Mediastinoscopy

Mediastinoscopy involves passing a scope into the mediastinum via an incision above the suprasternal notch. The scope is passed anterior to the trachea in close proximity to the left common carotid artery, left subclavian artery, innominate artery, innominate veins, vagus nerve, left recurrent laryngeal nerve, thoracic duct, superior vena cava, and aortic arch.

a) Large-bore IV access should be in place, and banked blood should be immediately available in the event of a tear in a major blood vessel, which is the most common severe complication.

b) Air embolism is also a risk if a venous tear occurs.

c) Arrhythmias such as bradycardia are possible with manipulation of the aorta or trachea during blunt dissection.

d) The mediastinoscope can place pressure on the innominate brachiocephalic artery as it passes through the upper thorax, causing a decrease in blood flow to the right common carotid artery and the right vertebral artery and a decrease in subclavian flow to the right arm. The decrease in cerebral flow could be detrimental, especially if the patient has a history of cerebrovascular disease.

e) Monitoring perfusion to the right arm with a pulse oximeter or radial artery catheter can detect decreased flow to the right arm and signal concurrent loss of flow to the brain via the innominate artery.

f) Repositioning of the mediastinoscope is required to reestablish flow to the brain.

g) A noninvasive blood pressure cuff placed on the left arm enables continued monitoring of systemic blood pressure during periods of innominate artery compression.

h) Complications of mediastinoscopy include pneumothorax, hemorrhage resulting from tearing of major vessels, arrhythmias, bronchospasm resulting from manipulation of the airway, laceration of the esophagus, and chylothorax secondary to laceration of the thoracic duct.

G One-lung ventilation

a) Indications for lung separation: The ability to provide distinct ventilation to the separate lungs facilitates pulmonary surgery by providing a quiet surgical field. This is particularly helpful in the case of thoracoscopic surgery, in which visualization and the ability to manipulate the operative lung are limited. Thoracic surgeons commonly consider lung separation an absolute requirement for pulmonary surgery. However surgery can be performed on a lung that is being ventilated, and thoracic surgery alone is not an absolute indication for one-lung ventilation (OLV). Certain situations, such as infectious contamination of one lung, are absolute indications for OLV. Most common thoracic surgeries create relative indications for lung separation because they can safely be accomplished without it. Indications for lung separation are noted in the following section.

b) Indications for separation of the two lungs (DLT intubation) or OLV

(a) Isolation of one lung from the other to avoid spillage or contamination

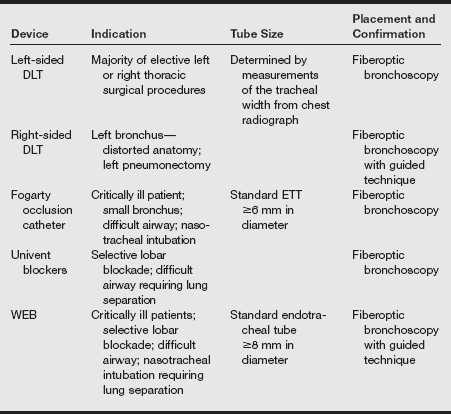

a) Methods of lung separation: Several devices have been developed to enable isolation of one lung and ventilation of the other. The single-lumen endobronchial tube provides a simple approach by advancing a 7.5-mm, 32-cm ETT over a fiberoptic scope into one bronchus (see the table below).

Summary of Lung Separation Devices and Recommendations for Placement

DLT, Double-lumen endotracheal tube; ETT, endotracheal tube; WEB, wire-guided endobronchial blocker.

From Campos JH. Lung separation techniques. In Kaplan JA, Slinger PD, eds. Thoracic Anesthesia. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2003.

(1) Bronchial blockers consist of catheters with an inflatable balloon that blocks the bronchus. A separate ETT is then placed into the trachea. Bronchial blockers are very useful in patients in whom the securing of the airway is anticipated to be difficult. Current options for stand-alone bronchial blockers include the 8 Fr-Fogarty embolectomy catheter and the wire-guided endobronchial blocker (WEB). The Fogarty catheter is useful in pediatric patients because it comes in smaller sizes. These blockers are inserted through a conventional ETT and guided into the appropriate bronchus using a bronchoscope.

(2) The Univent tube consists of an integrated ETT with a second lumen for a deployable bronchial blocker. After intubation of the trachea has been performed, the blocker is advanced into the bronchus with the aid of the fiberoptic bronchoscope. This tube is as easy to pass into the trachea as a single-lumen tube. The Univent tube is available in sizes from 6 to 9 mm internal diameter (although accounting for the blocker channel, the outer diameter is greater than that of a corresponding-sized ETT). Being of a shape and size more similar to conventional ETTs, the Univent may be a good alternative to a DLT in patients with difficult airways.

(3) DLTs consist of two bonded catheters, each with its own lumen; one lumen is used for ventilating the trachea and the other for ventilating the bronchus. Several types of DLTs have been used in thoracic surgery. The Carlens tube is a left-sided DLT with a carinal hook to aid in stabilization of the tube. Insertion is difficult, and the hook can cause vocal cord damage. A White tube is a right-sided DLT with a carinal hook.

(4) The Robertshaw DLT is available as a right- or left-sided DLT without a carinal hook. Disposable polyvinyl chloride tubes are available in French sizes 26, 28, 35, 37, 39, and 41. These correspond to internal lumen diameters ranging from 3.4 to 5 mm, respectively. Although the presence of dual lumens limits the internal diameter of each, the external diameter of a DLT is very large. The 37 Fr-DLT has an outer diameter equivalent to that of a standard 11.0 mm ID ETT. For this reason, DLTs are not used for small children; the external diameter of the 26 Fr-DLT is 7.5 mm. Sizing of DLTs is determined by patient height, usually leading to use of 35- to 37-Fr tubes in female patients and 39- to 41-Fr tubes in male patients.

(5) Modifications have been made in right-sided tubes to allow ventilation through a slot in the endobronchial cuff. It is thought that a greater margin of safety is associated with the use of a left-sided DLT for all right and left thoracotomies unless a left-sided tube is contraindicated.

(6) Contraindications to the use of DLTs include internal lesions of the trachea or main bronchi; compression of the trachea or main bronchi by an external mass; or the presence of a descending thoracic aortic aneurysm, which can compress or erode the left main bronchus. In these circumstances, it may be possible to use a DLT with the bronchial lumen on the unaffected side. Another contraindication is a difficult airway in which direct laryngoscopy is impossible. Intubation with the large DLT can pose a challenge even in patients with a normal airway; insertion in those with poor airway anatomy may require a creative approach.

(1) The DLT has two curves along its length to aid in its placement. A stylet aids placement through the larynx. Some practitioners prefer the Macintosh blade for intubation because it offers greater clearance for the tube and may decrease the chance of balloon rupture from the teeth.

(2) For laryngoscopy, the lubricated DLT is advanced with the distal curve concave anteriorly until the vocal cords are passed. The stylet is usually removed at this point. The tube is then rotated 90 degrees toward the bronchus to be intubated and advanced to around 27 cm depth in female patients or 29 cm in male patients or until resistance is met.

(3) Usually the stylet is removed after the tube has passed the glottis because of concern about the rigid tube causing mucosal damage. One study found that the success of initial placement was significantly improved by keeping the stylet in place until the tube was fully situated in the bronchus. This technique was not associated with increased tissue trauma.

(4) The tracheal cuff requires 5 to 10 mL of air, and the bronchial cuff requires 1 to 2 mL of air.

(5) Overinflation of the bronchial cuff can cause its lumen to be narrowed or occluded and increases the risk of tearing the bronchus. Unlike most tracheal high-volume, low-pressure cuffs, the bronchial cuff holds a small volume and can produce high pressures on the endobronchial mucosa. For that reason, the bronchial cuff should be deflated during the procedure once OLV is no longer needed.

(6) After the tube is situated in the bronchus, adapters are attached to the two lumens for interface with the anesthesia circuit. Auscultation of breath sounds is a simple, although not highly reliable, method of determining the position of a DLT, as listed in the following section.

c) Auscultation of breath sounds after placement of a DLT

(1) Inflate the tracheal cuff.

(2) Verify bilaterally equal breath sounds. If breath sounds are present on only one side, both lumens are in the same bronchus. Deflate the cuff and withdraw the tube 1 to 2 cm at a time until breath sounds are equal bilaterally.

(3) Inflate the endobronchial cuff.

(4) Clamp the endobronchial lumen, and open its lumen cap proximal to the clamp.

(5) Verify breath sounds in the correct lung and the absence of breath sounds in the opposite lung.

(6) Verify that breath sounds are equal at the apex of the lung and at the lateral lung. If the apex is diminished, withdraw the tube until upper lung sounds return.

(7) Verify the absence of air leakage through the opposite lumen cap.

(8) Unclamp the endobronchial lumen and verify bilateral breath sounds.

(9) Clamp the tracheal lumen and open its cap.

(10) Verify breath sounds on the side opposite the lung with the endobronchial lumen and the absence of breath sounds on the other.

(11) When absolute lung separation is needed, as in bronchopulmonary lavage, connecting a clamped lumen to an underwater drainage system will show air bubbles if a leak is present.

(12) Flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy is essential to verify placement of the DLT. Placement of the tube should again be verified by bronchoscopy after the patient is positioned laterally because the DLT will commonly withdraw from the bronchus by 1 cm.

(1) Placement of DLTs carries the same risks as laryngoscopy and intubation with ETTs. In addition, there exists a risk of hypoxemia with malpositioning of the tube.

(2) Rupture of a thoracic aneurysm is possible with a left DLT if the aneurysm compresses the left mainstem bronchus.

(3) Damage to the vocal cords or arytenoid cartilages is possible from a carinal hook. A carinal hook can also break off, requiring retrieval with a bronchoscope.

(4) Bronchial rupture, which was thought to be caused by overinflation of the bronchial cuff, has been reported. Because of the possibility of being inserted too deeply, a DLT can also cause the entire tidal volume to be delivered to a single lung lobe, creating the potential for barotrauma. Peak inspiratory pressures should be monitored closely to alert the anesthesia provider of possible migration of the DLT.

(5) The larger size of the DLT is probably also responsible for the slightly increased incidence of hoarseness and vocal cord lesions observed in patients after DLT versus using a bronchial blocker for lung separation. Vocal cord paralysis can represent a life-threatening complication of DLT placement.

(1) During two-lung ventilation (TLV), blood flow to the dependent lung averages approximately 60%. When one lung is allowed to deflate and OLV is started, any blood flow to the deflated lung becomes shunt flow, causing the Pao2 to decrease. Without autoregulation of pulmonary blood flow, a 40% shunt would be anticipated.

(2) The lungs have a compensatory mechanism of increasing vascular resistance in hypoxic areas of the lungs, and this diverts some blood flow to areas of better ventilation and oxygenation. This mechanism is termed hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction (HPV). HPV is an intrapulmonary reflex–feedback mechanism in inhomogeneous lungs to improve gas exchange and arterial oxygenation.

(3) Although hypoxemia causes vasodilation in the general circulation, it has the opposite effect on pulmonary arteries. HPV is a unique mechanism, suited specifically to match pulmonary blood flow with well-oxygenated areas of lung.

f) Characteristics of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction

(1) A local reaction occurring in hypoxic areas of the lung. It may be very localized because of regional atelectasis or OLV or may affect both lungs entirely in hypoxic situations.

(2) Opposite to systemic reaction, it causes vasoconstriction in response to hypoxia in all but very proximal pulmonary arteries.

(3) The onset and resolution are very fast after changes in tissue Po2.

(4) Triggered by alveolar hypoxia, not arterial hypoxemia

(5) May be inhibited by calcium channel blockade, volatile anesthetics, or vasodilators (see the box below.) Augmented by chemoreceptor agonists, HPV during OLV is effective in decreasing the cardiac output to the nonventilated lung to 20% to 25%. Shunt flow changes from 10% during TLV to 27% during OLV. This increase in shunt decreases the mean Pao2 from greater than 400 mmHg during TLV to slightly less than 200 mmHg during OLV when the fraction of inspired is 100%. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction can decrease the shunt fraction during OLV by 50%.

(6) HPV occurs whether the lung is rendered hypoxic by atelectasis or by ventilation with a hypoxic mixture. HPV improves arterial oxygenation when the amount of hypoxic lung is between 20% and 80%, which is the condition during OLV. When less than 20% of the lung is hypoxic, the total amount of shunt is not significant. When more than 80% of the lung is hypoxic, HPV increases pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), but the amount of well-perfused lung is not sufficient to accept shunt flow to maintain arterial oxygenation. This increase in PVR increases the work of the right side of the heart and can cause an increase in workload for the right ventricle.

3. Anesthetic technique during OLV

a) The primary goal during OLV is maintenance of adequate arterial oxygenation while providing a surgical field favorable for visualization and manipulation of the operative lung.

b) TLV should be maintained as long as possible and the time of OLV minimized. In the past, large Vts of 10 mL/kg (range, 8-15 mL/kg) were recommended to prevent atelectasis in the dependent lung and maintain an adequate functional residual capacity (FRC). Recent data suggest that most patients during OLV develop auto-positive end-expiratory pressure (auto-PEEP) and have an increased FRC. The use of a large Vt in that case may lead to trauma of the lung. Besides the direct physical effect, higher Vts are also associated with increases in inflammatory mediators and in alveolar fibrin deposition and other markers of procoagulant effect, which characterize acute lung injury.

c) The understanding of the detrimental effects of high tidal volumes has led to the more contemporary approach of using more physiologic volumes (6 mL/kg), adding PEEP to those patients without auto-PEEP, and limiting plateau inspiratory pressures to below 25 cm H2O. With this approach, patients maintain adequate or even improved oxygenation (compared with using higher Vt) and minimal elevations in Paco2. In any case, the effects of hypercapnia (consider the use of “permissive hypercapnia” as a strategy in treating severe lung injury) is far less detrimental than the potential trauma from excessive ventilation.

d) An appropriate air–O2 mixture, at times as high as an Fio2 of 1, is necessary to maximize the Pao2. However, after ascertaining that oxygenation will be stable after 30 minutes of OLV, the Fio2 should be reduced to lessen the effects of absorptive atelectasis.

e) The respiratory rate can be adjusted to maintain an adequate Paco2. Whereas a high Fio2 should induce vasodilation in the dependent lung, improving blood flow, hypocapnia would cause vasoconstriction and should be avoided. The relationship between Paco2 and end-tidal CO2 is not altered by OLV.

f) If hypoxemia occurs during OLV, the anesthesia provider should assess for physiologic causes or tube malpositioning. Physiologic causes may include bronchospasm, decreased cardiac output, hypoventilation, a low Fio2, or pneumothorax of the dependent lung. Tube malpositioning implies that movement of the DLT may have excluded a portion of dependent lung, usually the upper lobe. If physiologic causes have been ruled out and adequate lung separation and ventilation have been determined, one or more of the following interventions will help improve Pao2.

(1) First, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) to the nondependent, nonventilated lung is almost 100% efficacious in increasing Pao2. This can be accomplished with a compact breathing system, such as a Mapleson C with a manometer for pressure determination, attached to the lumen of the deflated lung.

(2) Alternatively, some DLTs can be purchased that include such a CPAP device with each tube. Application of CPAP should help to oxygenate the persistent blood flow through the nondependent lung, but too much pressure will cause the lung to inflate, reducing surgical exposure.

(3) The lowest level of effective CPAP (start at 2 cm H2O) should be sought. A CPAP device that incorporates a reservoir bag is also useful for providing intermittent ventilation to the operative lung, if that intervention become necessary. Providing gentle ventilation with a separate system will minimize the diminution of surgical exposure, as opposed to ventilating the lung with the same vigor as that required for the dependent lung.

(4) If CPAP to the nondependent lung does not improve oxygenation, PEEP applied to the dependent, ventilated lung acts to increase Pao2 by recruiting collapsed airways, increasing compliance of the lung, and increasing FRC. Excessive PEEP may also detrimentally reduce cardiac output. Combined with a fast respiratory rate and/or high tidal volume, PEEP may impair adequate exhalation, leading to a net volume increase through “auto-PEEP” and lead to the potential for trauma to the dependent lung. The actual end-expiratory pressure should be monitored during OLV to assure that it does not significantly exceed the intended level of PEEP. Although the intention of PEEP is to recruit collapsed alveoli, overdistention of alveoli with excessive PEEP may increase the areas of zone 1 effect (alveolar pressure exceeding capillary pressure) and create more dead space ventilation.

(5) Other methods of improving oxygenation during OLV include combining PEEP and CPAP to the respective lungs and intermittent reinflation of the nondependent lung.

(6) The use of different modes of ventilation, such as pressure control, may provide a different distribution of ventilation and improve oxygenation as well. Emerging in this area is the use of innovative ventilatory approaches, such as high-frequency jet ventilation to the operative lung, and jet ventilation selectively to nonoperative lobes of the operative lung via a bronchial blocker with insufflation port.

(7) In the failure of CPAP and PEEP, early ligation of the pulmonary artery in pneumonectomy patients may be used to improve oxygenation. If the pulmonary artery is planned to be ligated during the procedure, clamping it will immediately stop all significant flow through the lung that is contributing to the shunt.

(8) If it becomes impossible to maintain adequate oxygenation with OLV despite CPAP and PEEP, manual TLV can be used, with pauses in ventilation coordinated with the surgeon’s activities to facilitate exposure, suturing of the lung, or other needs.

g) Communication with the surgical team is vital throughout the procedure, especially during the evaluation and correction of hypoxia.

h) At the conclusion of the resection, the surgeon will commonly ask that the operative lung be reinflated using large tidal volumes, so that air leaks may be detected. At this time, the lung separator (DLT clamp, bronchial blocker) should be discontinued, and the lung inflated with slow breaths, achieving a peak inspiratory pressure of 30 to 40 cm H2O. Reexpansion of the lung can be observed while performing this maneuver, which also helps to reverse atelectasis in the lungs. After lung reexpansion, the bronchial cuff should be deflated on the DLT to both reduce pressure on the bronchial mucosa and to obviate any detrimental effects of slight tube malpositioning. Deflated, the cuff does not pose the threat of herniating over the carina, obstructing the right upper lobe takeoff, and so on.

H Thoracoscopy

Advances in videoscopic technology have led to the increased use of thoracoscopy. The procedure used most commonly involves placing the patient in the lateral decubitus position. A trocar is introduced at the fourth to fifth or fifth to sixth intercostal space to allow passage of the thoracoscope. Additional trocars and cannulas can be passed to insert suction, cautery, or other instruments. Drainage and examination of the pleural space lobectomy, debridement of an empyema, removal of foreign bodies, instillation of chemotherapeutic agents into the pleural space, pleurodesis with physical abrasion or talc, stapling of blebs, diagnostic biopsies and staging, and evaluation of bronchopleural fistulas are some of the procedures possible with thoracoscopy.

a) Thoracoscopy has been performed under epidural anesthesia alone, and this technique is associated with the typical advantages of regional over general anesthesia.

b) General anesthesia with a double lumen ETT (DLT) is most common and offers several advantages for thoracoscopy. The airway is secured before lateral positioning. This avoids the need to change to general anesthesia under less-than-optimal conditions if regional anesthesia or sedation techniques fails. It allows for deflation of the lung before the introduction of the trocar.

(2) Perform manual ventilation.

(4) Apply CPAP to the nonventilated (operative) lung.

(5) Apply PEEP to the ventilated lung.

(6) Reinflate the operative lung.

(7) Perform pulmonary artery clamping of the pulmonary artery segment that supplies the operative lung.

d) Controlled ventilation helps prevent paradoxic respiration and mediastinal shift, and the lung can be actively reinflated at the end of the procedure.

e) Regardless of the anesthetic used, the anesthesia provider should always be prepared for a switch to an open thoracotomy if the surgeon encounters complications or becomes unable to complete the procedure by thoracoscopy.

f) An arterial line is generally placed for thoracoscopy except in selected healthy patients. Patients for thoracic procedures are generally at risk for cardiopulmonary morbidity. Because of the ventilation–perfusion mismatch that accompanies OLV, the anesthetic plan should account for the potential need for rapidly obtaining arterial blood gas samples.

g) Thoracoscopic sympathectomy for hyperhidrosis is an outpatient procedure. A DLT is preferred over a bronchial blocker because the procedure is bilateral. Positioning the DLT once at the beginning of the case so that each lung can be deflated one at a time is much easier than repositioning a bronchial blocker into the opposite bronchus after one side has been completed. The patient is in the supine position, and no chest tubes are inserted. Air and O2 are preferred carrier gases.

h) Pain after a thoracoscopy is generally more easily managed than after an open thoracotomy. The incision length is smaller, and spreading of the ribs is avoided. Adequate pain relief is commonly obtained with the use of oral analgesics or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. More extensive procedures such as decortication and pleurodesis often require parenteral narcotics. An intercostal block may also be used to treat pain from manipulation of the thoracoscope in the camera port.

I Thoracotomy

Thoracotomy is usually performed in an attempt to resect malignant lung tissue, but it may also be performed for trauma; infections; and parenchymal abnormalities, such as recurrent blebs. Because thoracotomy involves incising the pleura, all patients require a chest tube postoperatively. Most patients are older than 40 years and have a history of smoking. Many also have associated cardiovascular disease.

a) Preoperative evaluation of patients for pulmonary surgery (see the table below).

Initial Preanesthetic Assessment for Thoracic Surgery

| Patient Type | Assessments |

| All patients | Assess exercise tolerance, estimate PPO FEV1%,* discuss postoperative analgesia, consider discontinuation of smoking |

| Patients with PPO FEV1 <40% | Dlco, V./Q. scan, Vo2 max |

| Patients with cancer | Consider the “4 Ms”: mass effects, metabolic effects, metastases, medications |

| Patients with COPD | ABG analysis, physiotherapy, bronchodilators |

| Patients with increased renal risk | Measure creatinine and BUN |

ABG, Arterial blood gas; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Dlco, diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; PPO, predicted postoperative; Vo2 max, maximum oxygen consumption; V/Q, ventilation–perfusion ratio.

*PPO FEV1% = Preoperative FEV1 % × (1% of functioning lung tissue removed/100). For values above 40%, postoperative complications are rare; for values between 30% and 40%, postoperative problems are possible; for values below 30%, postoperative ventilation is likely to be required.

Modified from Slinger PP, Johnston MR. Preoperative assessment and management. In Kaplan JA, Slinger PD, eds. Thoracic Anesthesia. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2003.

(1) Contraindications for lung resection surgery relate to preoperative testing (cardiovascular and pulmonary) and the patient’s inability to tolerate the physiological stress of the procedure.

(2) Patients should undergo cardiologic evaluation. Unstable angina, myocardial infarction within 6 weeks, or significant arrhythmias predict a high risk of cardiac complications.

(3) Before lung resection, spirometry should be performed. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) greater than 80% of predicted or greater than 2 L indicates minimal risk; further testing is not indicated. FEV1 less than 40% of predicted indicates a high risk for complications or death.

(4) With evidence of interstitial lung disease or dyspnea, Dlco (diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide) should be measured. Dlco below 60% predicts increased complications; below 40% equals high risk.

(5) If FEV1 or Dlco is below 80% of predicted, postoperative lung function should be estimated.

(6) If preoperative or predicted postoperative FEV1 or Dlco is below 40% of predicted normal, exercise testing should be performed. A VO2 max (maximal oxygen consumption) above or below 15 mL/kg/min) will dispute or confirm the risk conferred by the low FEV1. An inability to climb one flight of stairs, VO2 max below 10 mL/kg/min, or desaturation greater than 4% during exercise, indicates a high risk for complications or mortality.

(7) Lung volume reduction surgery may be associated with improved outcomes beyond what preoperative measurements would suggest.

a) Laboratory tests include a complete blood count, electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, glucose, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, arterial blood gases, and type and crossmatch for at least 2 units (depending on the type of surgery and the patient’s hemoglobin).

b) Digitalization is recommended prior to pneumonectomy to help prevent postoperative heart failure. It will also reduce tachyarrhythmias intraoperatively.

c) Have inhaled bronchodilators readily available. Many practitioners administer them prophylactically.

d) Administer an antisialagogue, such as glycopyrrolate, to ease placement and verification of the DLT.

a) Monitoring: This is standard, with an arterial line. A central venous pressure (CVP) is placed in patients with preexisting heart disease. Keep in mind that CVP readings may be inaccurate while the chest is opened.

b) Additional equipment includes DLTs (at least two). (Balloon rupture on insertion is common.) A fiberoptic endoscope is used to check tube placement. Equipment is needed to add CPAP and PEEP intraoperatively. Epidural catheter insertion and infusion supplies are indicated (if used). Warming devices are needed for the patient and fluids.

c) Positioning: Lateral or supine with lateral tilt. A beanbag, arm “sled,” and axillary rolls may be used. Check for lack of pressure on the downward arm, eye, and ear. Ensure that the patient’s arms are not hyperextended.

d) Drugs and fluids: It is preferable to err on the side of underhydrating because these patients are prone to pulmonary edema. Usually, one gives use of no more than 4 to 5 mL/kg/hr. Have ephedrine/phenylephrine available to treat hypotension.

5. Perioperative management and anesthetic technique

a) Use standard induction techniques, keeping in mind that the positioning and placement of a DLT require more time than does standard tube placement.

b) Preoxygenate these patients.

c) Arterial blood gases are obtained after induction for baseline, so they may be compared with later results on OLV.

d) During OLV, maintain tidal volume between 6 to 8 mL/kg and place the patient on 100% oxygen. If hypoxemia is present (verify tube placement first), add 5 cm of CPAP to the “upward” (surgical) lung. If hypoxemia is still present, add 5 cm of PEEP to the “downward” (ventilated) lung.

e) Extubation at the end of the procedure is preferable unless the patient had a preoperative respiratory indication for remaining intubated (e.g., bronchospasm) or there were large fluid shifts. If the patient needs to remain intubated, the DLT should be replaced with a standard ETT.

f) For patients with oat cell (small cell) carcinoma, consider the possibility of Eaton-Lambert syndrome.

Epidural anesthesia, patient-controlled analgesia, or another type of pain control (e.g., nerve block) should be planned preoperatively. The patient must understand and be able to perform deep-breathing exercises. Institute intensive care unit monitoring for at least 24 hours.

J Thymectomy

The thymus gland is a bilobate mass of lymphoid tissue located deep into the sternum in the anterior region of the mediastinum. Thymectomy involves two surgical approaches: median sternotomy or transcervical.

The thymus gland is believed to play a role in myasthenia gravis. This is a neuromuscular disorder in which postsynaptic acetylcholine receptors are attacked, inducing rapid receptor destruction.

2. Preoperative assessment and patient preparation

a) History and physical examination

(1) Respiratory (based on the patient with myasthenia gravis)

(a) Weakness of pharyngeal and laryngeal muscles is associated with a high risk of aspiration. Assess the patient’s ability to cough and handle secretions.

(b) “Myasthenic crisis”: This exacerbation involves the respiratory muscles to the point of inadequate ventilation.

(1) Pulmonary function studies are obtained as indicated.

(2) Laboratory tests include electrolytes, complete blood count, type and screen, and others as indicated by the patient’s medical condition.

c) Preoperative medications and IV therapy

(1) Cholinesterase inhibitors retard the enzymatic hydrolysis of acetylcholine at cholinergic synapses and cause acetylcholine to accumulate at the neuromuscular junction. Continue up to the morning of scheduled surgery.

(a) These drugs interfere with production of antibodies that are responsible for degradation of cholinergic receptors.

(b) Patients who have been receiving steroids for more than 1 month in the past 6 to 12 months need supplementary steroids.

(3) Antisialagogues and H2 (histamine2-receptor) blockers: Patients with bulbar involvement should be evaluated to determine the safety of these drugs.

(4) Sedatives and narcotics: Use with caution in patients with poor respiratory reserve.

(6) An 18-gauge IV catheter with moderate fluid replacement is used.

a) Monitoring equipment: Standard

(1) An arterial line is placed if blood gas monitoring is necessary.

(2) Some suggest placing the arterial catheter in the left radial artery for continuous monitoring in case the innominate artery is damaged.

4. Anesthetic technique and perioperative management

General anesthesia is used, and endotracheal intubation is required.

(1) When anesthetizing patients with myasthenia gravis, avoidance of all muscle relaxants is preferred.

(2) An inhaled anesthetic by itself should provide sufficient relaxation of skeletal muscle for intubation of the trachea.