Joints and connective tissues

HISTORY AND EXAMINATION

Some arthropathies present with an acute onset of pain, with peak intensity reached within hours or days; in others it occurs gradually over weeks to months. The clinical pattern may be monarticular, oligoarticular or polyarticular. Variations of these patterns may occur within the same disorder. For example, rheumatoid arthritis may present as an acute monarthritis of the knee before spreading to other joints, or as an acute polyarthritis. Although almost any arthropathy may begin as a monarthritis, the initial pattern of certain disorders is characteristically monarticular, with pain, redness and swelling. Certain diagnoses, such as infection or crystal arthritis, should be suspected in this situation (see Box 33.2). Infectious monarthritis is an important diagnosis to make early, as joint damage can occur if untreated.

Chronic monarthritis is the presenting manifestation of a variety of joint disorders, some of which are listed in Box 33.3. Involvement of two to four joints is usually referred to as oligoarthritis. There are a number of conditions in which involvement of two or three joints rather than one may significantly narrow the differential diagnosis, including pseudogout and psoriatic arthritis. The third pattern is the one in which polyarticular involvement dominates the clinical picture. A variety of inflammatory and non-inflammatory disorders, both common and uncommon, may present as polyarthritis (see Table 33.1).

BOX 33.3 Common causes of chronic monarthritis

TABLE 33.1 Distribution of common oligo- and polyarthritides

| Symmetric | Asymmetric | |

|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory |

AETIOLOGY

The accepted aetiology of the common arthropathies is as follows:

DIAGNOSIS

IMAGING PROCEDURES

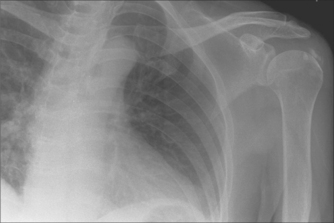

X-rays

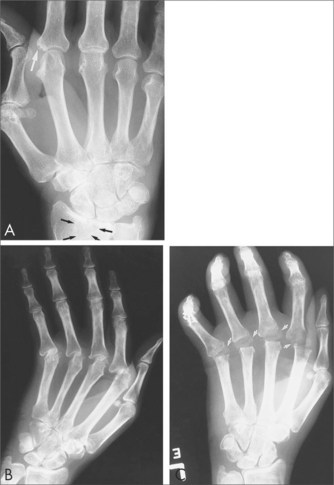

Plain X-rays often provide useful diagnostic information in patients with inflammatory or degenerative arthritis (see Table 33.2).

TABLE 33.2 Typical X-ray findings in osteoarthritis vs rheumatoid arthritis

| Osteoarthritis | Rheumatoid arthritis | |

|---|---|---|

| Joint space narrowing | Yes | Yes |

| Erosions | No | Yes |

| Periarticular osteoporosis | No | Yes |

| Subchondral sclerosis | Yes | No |

Ultrasound

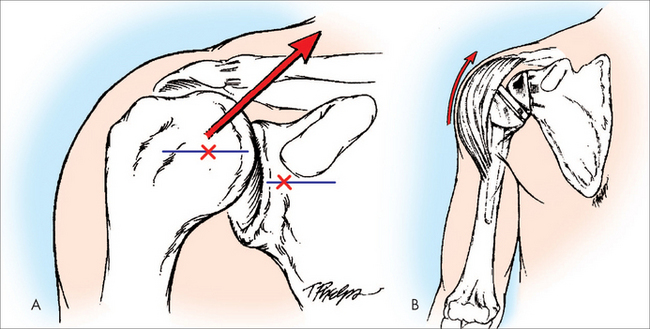

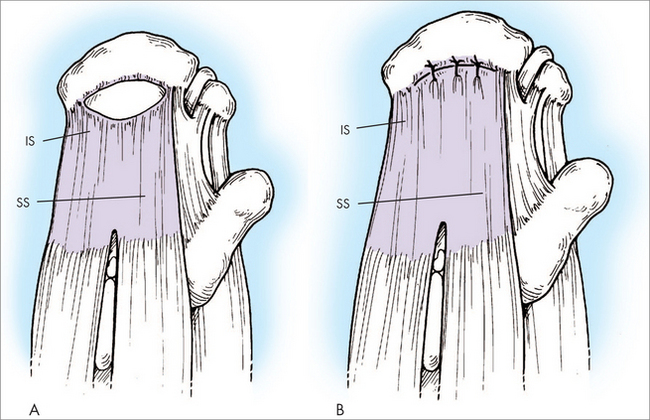

Ultrasound is a more expensive imaging modality used for a wide range of arthritic conditions. Tendon and muscle abnormalities such as rotator cuff tears can be diagnosed using the technique. Synovial effusions, synovial hypertrophy and inflammation can be evaluated using ultrasound. Power Doppler can be used for assessing synovial membrane inflammation. It is important to note that the effectiveness of ultrasound is very much dependent on the experience of the operator.

LABORATORY TESTS

Extractable nuclear antigens

Extractable nuclear antigens (ENAs) may provide further information about the diagnostic subgroup in patients with a positive ANA (see Table 33.3).

| Subtype | Associations |

|---|---|

| Sm | SLE |

| SS-A | Sjögren’s syndrome, SLE |

| SS-B | Sjögren’s syndrome, SLE |

| RNP | Mixed connective tissue disease |

| Anti-centromere | CREST (limited scleroderma) |

| Jo-1 | Dermatomyositis |

| Scl-70 | Diffuse scleroderma |

Rheumatoid factor

Rheumatoid factors may be found in up to 5% of young healthy individuals; the higher the titre, the greater the likelihood that the patient has rheumatic disease. Rheumatoid-factor-positive patients with rheumatoid arthritis generally experience more aggressive and severe erosive joint disease as well as more extraarticular manifestations than those who are rheumatoid factor negative. However, there is wide inter-patient variability.

MANAGEMENT OF DISORDERS

EDUCATION

With an acute self-limiting form of musculoskeletal problem or arthritis, treatment can be self-limiting and education is not required. With chronic forms of musculoskeletal disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis, education is important and the healthcare professional acts as informed adviser to the patient. Management plans must be mutually agreed.

THERAPEUTIC STRATEGIES

Therapeutic strategies in musculoskeletal conditions can be considered non-pharmacological, pharmacological or surgical (see Box 33.4).

INTEGRATIVE APPROACH TO THERAPY

Herbal

Supplements

Fish oil

Because Western diets are typically low in long-chain omega-3 PUFA, substantial increases in tissue long-chain omega-3 can be achieved by taking a fish oil supplement without additional dietary modification. However, a choice of spreads that are rich in omega-3 PUFA or rich in monounsaturated fatty acids and low in omega-6 PUFA allow higher tissue omega-3 levels to be reached with a given dose of fish oil. To achieve anti-inflammatory doses of long-chain omega-3 PUFA by simply eating fish, a substantial dietary intake is required—greater than would be practical for most people. A daily intake of 2.7 g of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids is the threshold amount that has been shown consistently to deliver an anti-inflammatory effect in groups of patients in randomised trials2 and is found in 10 mL of standard fish oil (from a bottle of fish oil) daily or nine standard 1000 mg capsules daily. People taking one or two capsules daily will generally have an insufficient dose for any anti-inflammatory effect in conditions like rheumatoid arthritis.

Glucosamine and chondroitin

Numerous studies indicate that glucosamine alone or combined with chondroitin provides symptomatic benefit for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. However, a lack of standardisation in glucosamine preparations has contributed to inconsistency in study results across trials. A recent updated Cochrane review of glucosamine therapy in osteoarthritis found that pain and function improved by 28% and 21% respectively, compared with placebo.3 A large NIH-sponsored study found that the combination of glucosamine hydrochloride and chondroitin sulfate was more effective than placebo only in the subgroup with moderate to severe osteoarthritis.4

There may also be some effect on ‘disease modification’—that is, not just symptoms. In a landmark trial assessing the disease modifying potential of glucosamine sulfate, patients were randomly assigned 1500 mg daily of glucosamine with placebo for 3 years. Patients on placebo had progressive joint space narrowing, whereas no significant joint space loss was seen in patients taking glucosamine.5 The results have since been questioned because of the radiographic technique used to measure joint space width,6 and further studies using MRI are needed.

Recommended dose: glucosamine 1500 mg per day; chondroitin 1200 mg per day.

PHARMACOLOGICAL

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

In susceptible individuals, NSAIDs are nephrotoxic, by inhibiting prostaglandin-dependent compensatory renal blood flow. Recent studies have also identified an increased risk of cardiovascular events with these agents,7 suggesting that natural inhibition of COX by fish oils may have certain advantages (see below).

Intraarticular and local injection therapy

Viscosupplementation with hyaluronic acid injections has also been used in osteoarthritis. Although no direct comparison between specific products has been performed, viscosupplementation was more efficacious from 5 to 13 weeks with regard to pain, range of motion and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Index of Osteoarthritis (WOMAC) and Lesquene scores, than placebo.8 In Australia, the only compound available is hylan G-F 20 (SYNVISC®). It does not attract PBS reimbursement and is only approved for knee osteoarthritis.

Arthritis Australia. http://www.arthritisaustralia.com.au.

Cleland LG, James MJ, Proudman SM. Fish oil: what the prescriber needs to know. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:202.

Hochberg M, Silman A, Smolen J, et al. Rheumatology. 3rd edn. London: Mosby, 2003.

March L, Ananda A. Management of osteoarthritis: part 2. Medical Observer. 2007;20 April:27-30.

Sambrook P, Schrieber L, Taylor T, et al. The musculoskeletal system. London: Churchill Livingstone, 2001.

1 Linde K, Berner MM, Kriston L. St John’s wort for major depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;3:CD000448.

2 Proudman SM, Cleland LG, James MJ. Dietary omega-3 fats for treatment of inflammatory joint disease: efficacy and utility. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2008;34(2):469-479.

3 Towheed T, Maxwell L, Anastassiades TP, et al. Glucosamine therapy for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;4:CD002946.

4 Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Harris CL, et al. Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:795-808. 858–860.

5 Reginster JY, Deroisy R, Rovati LC, et al. Long-term effects of glucosamine sulphate on osteoarthritis progression: a randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2001;357:247-248.

6 McAlindon T. Glucosamine for osteoarthritis: dawn of a new era? Lancet. 2001;357:247-248.

7 Mukherjee D, Nissen SE, Topol EJ. Risk of cardiovascular events associated with selective COX-2 inhibitors. JAMA. 2001;286(8):954-959.

8 Bellamy N, Campbell J, Robinson V, et al. Viscosupplementation for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2:CD005321.