Anatomy of the Urethra

The female urethra is about 4 cm long and averages 6 mm in diameter. Its lumen is slightly curved as it passes from its internal position in the retropubic space, perforates the perineal membrane, and ends by opening into the vestibule directly above the vaginal opening. Throughout its length, the posterior urethra is embedded in the anterior vaginal wall.

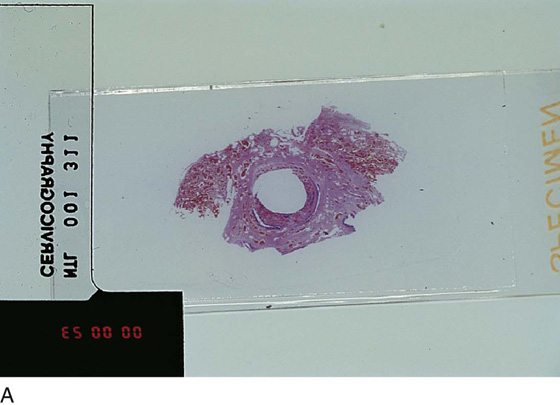

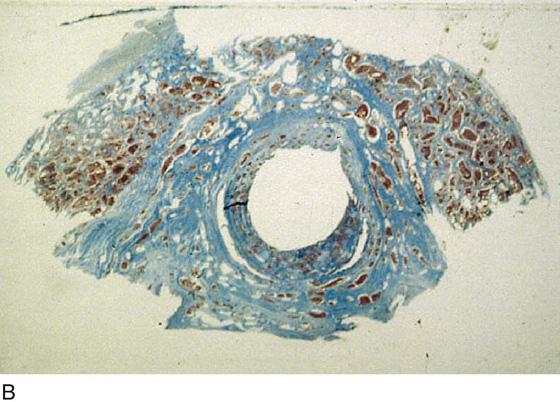

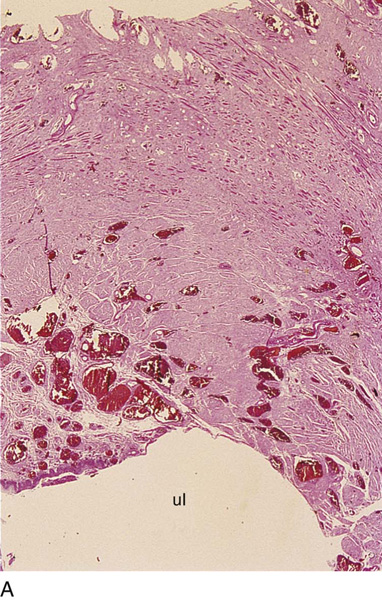

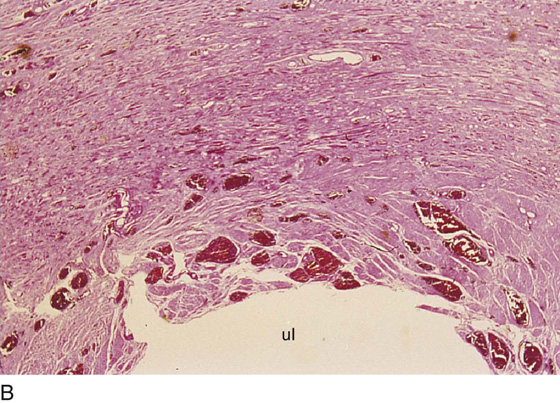

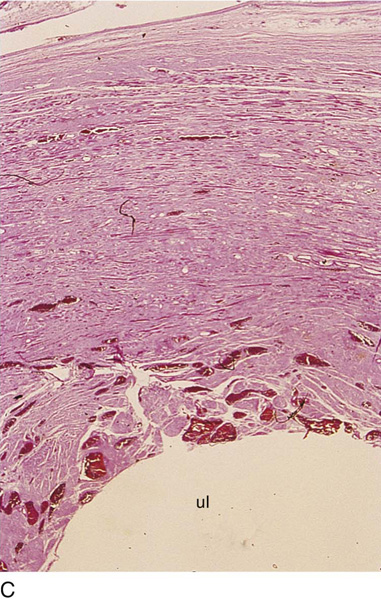

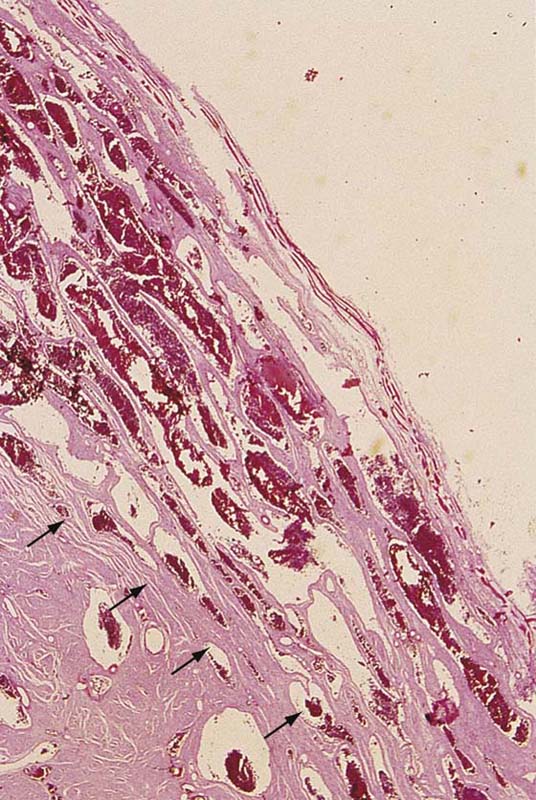

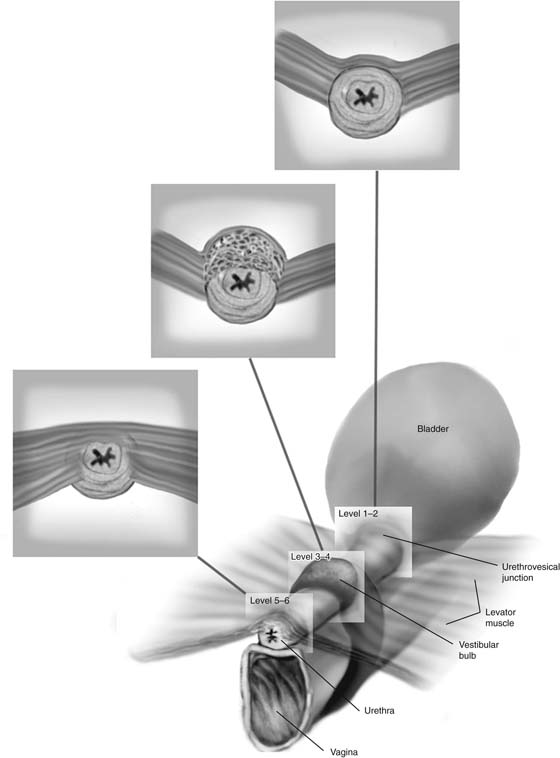

The epithelium of the urethra is continuous externally with that of the vulva and internally with that of the bladder. It consists primarily of stratified squamous epithelium that becomes transitional near the bladder. The epithelium is supported by a layer of loose fibroelastic connective tissue—the lamina propria. The lamina propria contains many bundles of collagen fibrils and fibrocytes, as well as an abundance of elastic fibers oriented both longitudinally and circularly around the urethra. Numerous thin-walled veins are another characteristic feature. This rich vascular supply is thought to contribute to urethral resistance. Cross-sections of the urethra below the urethrovesical junction at 6 to 9 mm (distal) clearly show the cavernous vascularity that contributes more than 50% of the volume of tissue constituting the anterior and lateral walls of the urethra (Fig. 81–1A through D).

The smooth muscles of the urethra are composed primarily of oblique and longitudinal muscle fibers with a few circularly oriented outer fibers. This smooth muscle, along with the detrusor muscle in the bladder base, forms what can be called the intrinsic urethral sphincter mechanism. Longitudinally directed muscle probably shortens and widens the urethral lumen during micturition, whereas circular smooth muscle contributes to urethral resistance to outflow at rest.

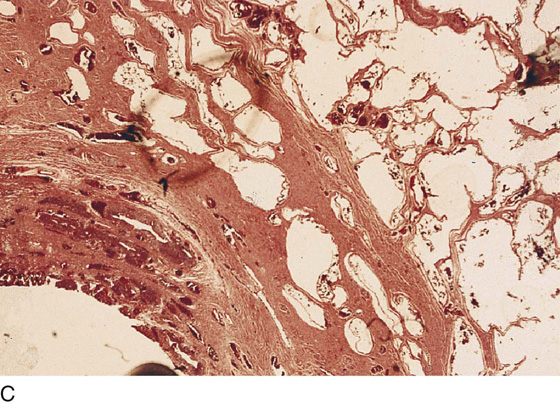

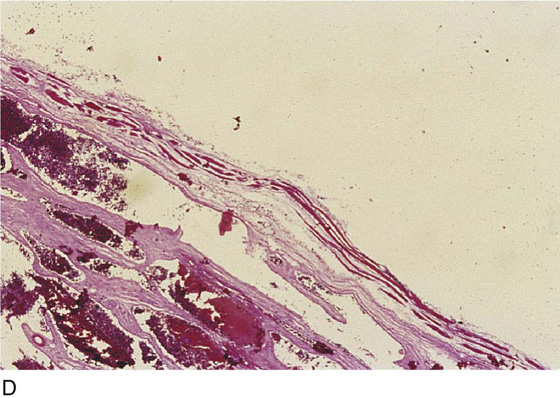

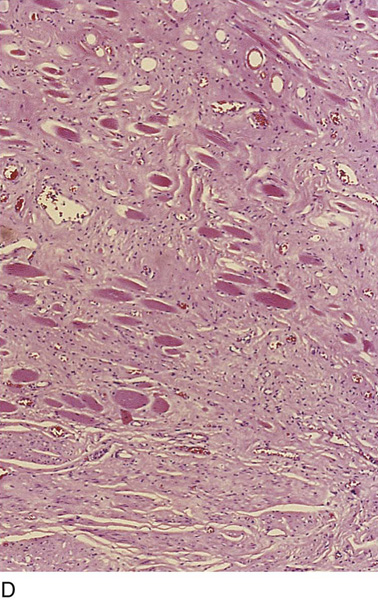

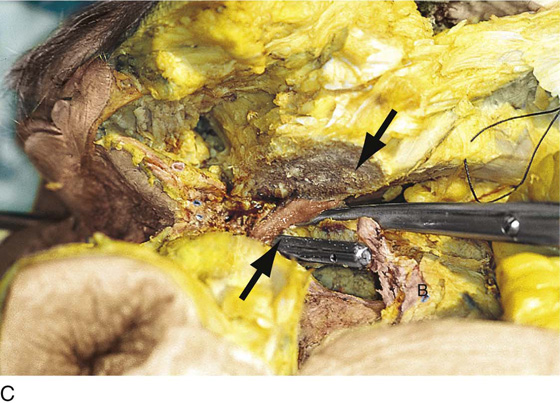

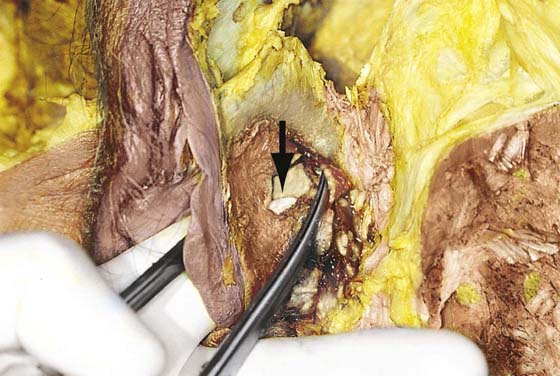

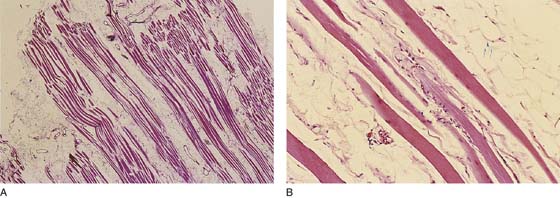

Historically, striated muscle termed the striated urogenital sphincter has been divided into three muscles: the sphincter urethrae, which is described as a striated band of muscle that surrounds the proximal two thirds of the urethra, and the compressor urethrae and urethrovaginal sphincter, which consist of two straplike bands of striated muscle that arch over the ventral surface of the distal third of the urethra. The authors’ recent dissections on multiple female cadavers with gross and microscopic examination of this area revealed no separate or distinct striated musculature of the urethra. The authors were unable to identify any striated musculature in the periurethral area that was not an extension of the levator ani muscle (Fig. 81–2A through G). In a series of 12 cadaveric dissections, the levator ani muscle was thought to extend over the anterior surface of the urethra. The authors were thus unable to identify the previously described separate and distinct striated urogenital sphincter. Figs. 81–3 through 81–6 are gross and microscopic sections showing the levator muscle over the urethra. In performing histologic sections throughout the length of the urethra, the authors also observed that most of the vascular contribution of the urethra stemmed from the bulb of the vestibule. The vascularity created an umbrella-type effect over the anterior and lateral walls of the urethra (Figs. 81–1B and 81–7).

Urethral support, which is thought to be important in the continence mechanism, has traditionally been thought to be provided by the inner action of the pubourethral ligaments, the urogenital diaphragm, and the muscles of the pelvic diaphragm. Numerous investigators have described the so-called pubourethral ligaments as extending from the inferior surface of the pubic bones to the urethra. More recently, it has become apparent that the urethra is not suspended ventrally by ligamentous structures, but instead the proximal urethra and bladder base are supported in a slinglike fashion by the anterior vaginal wall, which is attached bilaterally to the muscles of the pelvic sidewall at the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis, or white line. The tissues previously described as pubourethral ligaments are in actuality made up of the perineal membrane and the most caudal portions of the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis, which fix the distal urethra beneath the pubic bone (Fig. 81–8).

FIGURE 81–1 A. This section clearly shows the cavernous tissue making up an integral portion of the anterior urethral wall between 11 and 1 o’clock (6 to 9 mm distal to the urethrovesical junction) (H & E). B. This section at 9 mm below the urethrovesical junction shows the smooth muscle of the urethra, as well as the umbrella of cavernous tissue (pink) forming the major portion of the anterior and anterolateral wall of the urethra. C. High-power view of the anterolateral wall of the urethra. The cavernous bulb tissue is closely applied to the urethra. D. A thin layer of skeletal muscle probably derived from the bulbocavernosus muscle overlies the cavernous (bulb) tissue of the urethra.

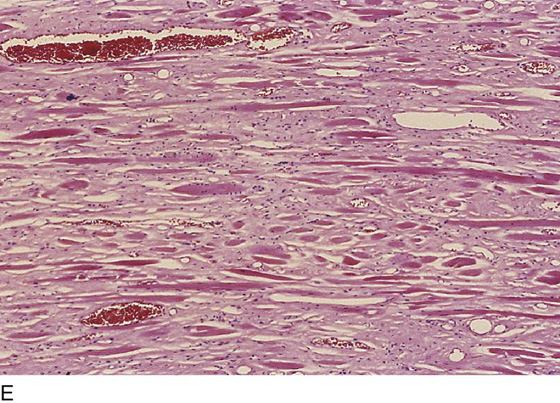

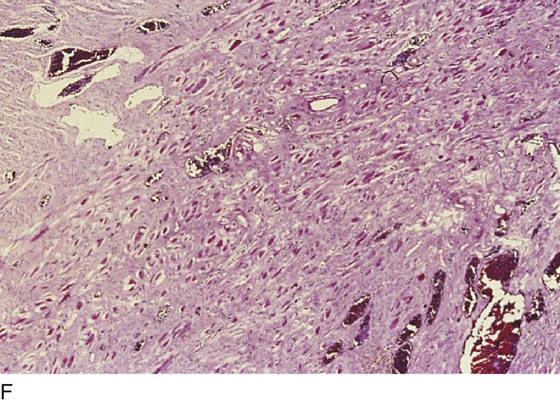

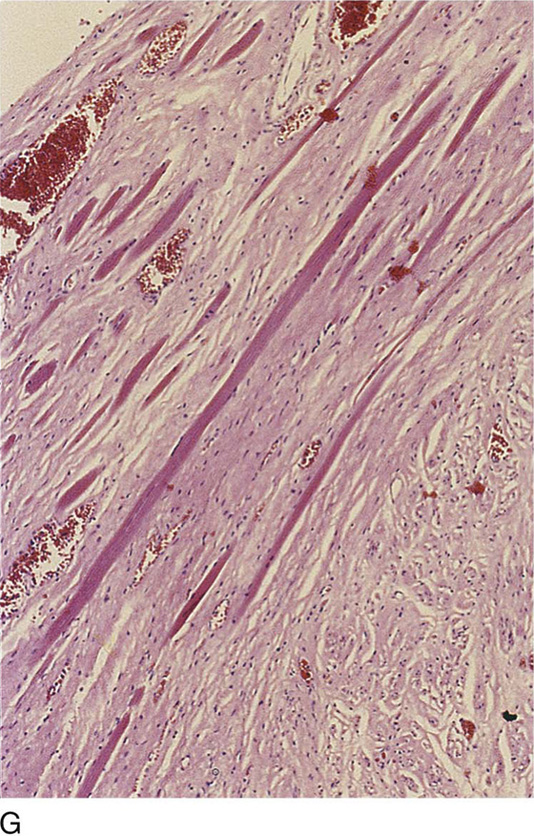

FIGURE 81–2 A. This section of the anterior urethra is obtained at 15 mm below (distal to) the urethrovesical junction. Anterior to (above) the lumen (ul), with its rich vascular submucosa, is the thickened anterior urethral wall. The deep pink tissue (outer half) is skeletal muscle derived from the levator ani muscles. B. This section is obtained at level 6, or 18 mm distal to the urethrovesical junction. The anterior urethral wall is dense pink tissue, and the upper three fourths of the wall consists of skeletal muscle. C. Another view at level 6 confirms the layers of skeletal muscle making up the greatest mass volume of the anterior urethra. D. High-power view of the deep pink skeletal muscle seen in parts B and C. E. High-power view of the skeletal muscle of the anterior urethral wall (different cut level than part D). F. The anterolateral wall of the urethra similarly shows a mass of skeletal muscle (11 o’clock position). G. Similar cut at the lateral outer urethral wall shows the deep-pink staining skeletal muscle 20 mm distal to the urethrovesical junction. The muscle is derived from the levator ani muscle.

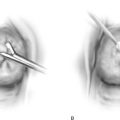

FIGURE 81–3 A. A metal cannula is seen in the opened bladder. The arrow points to where the pubic bone was sawed away. A mass of skeletal muscle inserts into the urethrovesical junction and originates from the levator ani below the pubic ramus (tip of scissors). B. The bladder (B) is opened with a transurethral cannula seen protruding from the bladder (B) lumen. The arrow points to the sawed pubic bone. The scissors point to skeletal muscle at the urethrovesical junction. C. The lower arrow points to a continuation of the descending levator ani muscle from beneath the pubic bone, which is in continuity from the levator below the white line. It enters the urethrovesical junction laterally and anteriorly.

FIGURE 81–4 The arrow points to the subpubic levator fibers at the urethrovesical junction. The scissors have dissected beneath the clitoral crus and point to the muscle mass. The steel cannula emerges into the opened (cut) bladder base. P, Cut edge of pubic bone.

FIGURE 81–5 The operator’s left index finger is inserted through the introitus into the vagina. The metal cannula on the gloved finger has been inserted into the external urethral meatus. The scissors point to the left vestibular bulb. The arrow points to the thin outer (but intact) wall of the urethra. The white gloved fingertip can be seen via an opening in the lateral vaginal wall.

FIGURE 81–6 A. Sample of the muscle bundle descending from beneath the pubic ramus (see Figs. 55–3 and 55–4) to insert into the lateral and anterior urethral wall at the urethrovesical junction. The muscle is clearly skeletal. B. High-power view showing cross-striations of skeletal muscle.

FIGURE 81–7 This high-power view shows the relationship of the anterolateral cavernous bulb tissue to the vascularity above the urethral mucosa. The arrows indicate the boundary between the cavernous tissue and the smooth muscle of the urethral wall.

FIGURE 81–8 Schematic view of the relationships of cavernous and skeletal muscle based on serial histologic cuts from the proximal to the distal urethra. The skeletal muscle is derived from the levator ani muscles on either side of the pelvis and descends from beneath the pubic rami. The cavernous tissue takes its origin mainly from the bulb of the vestibule but also from the clitoral body and crura (at the point of fusion to the clitoral body).

Mickey M. Karram

Mickey M. Karram