Anatomy of the Support of the Anterior and Posterior Vaginal Walls

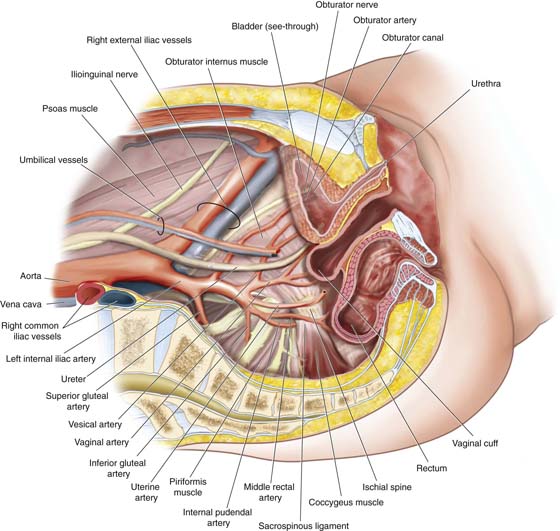

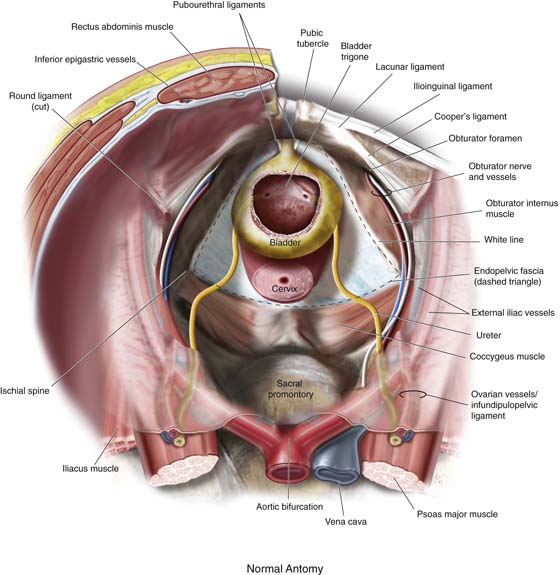

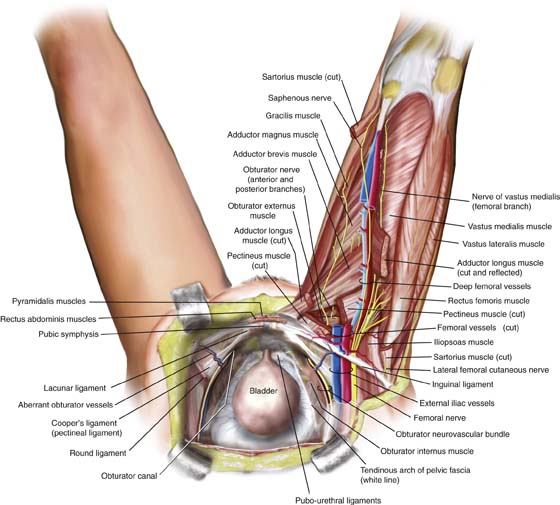

To safely perform procedures on the female pelvic floor, it is imperative that the surgeon has a good three-dimensional understanding of the anatomy in this area. This includes a full appreciation of where important blood vessels and nerves travel, as well as of the relationships between various structures used to support pelvic viscera. Figure 52–1 is a cross-sectional view of the pelvis, demonstrating the relationships of various blood vessels to the vagina, pelvic viscera, ureter, and coccygeus–sacrospinous ligament complex. Figure 52–2 demonstrates the support of the anterior vaginal wall viewed through the retropubic space. Note the white area labeled as the inside of the vaginal wall. In a woman with a well-supported anterior vaginal wall, it is attached to the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis (labeled as white line) laterally and the cervix or vaginal cuff proximally. Because many procedures for incontinence and prolapse involve the passing of needles and trocars through the inner thigh, a firm understanding of the anatomy of the structures in this area is necessary. Figure 52–3 reviews this anatomy as it relates to the retropubic space and vagina.

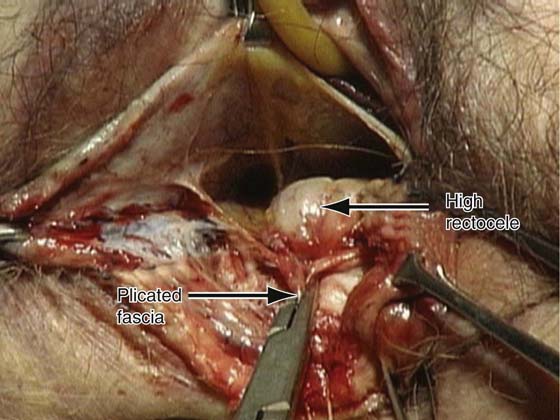

After the lower, middle, and upper thirds of the vagina are viewed, from the gross dissection it is helpful to consider what can be seen when the vagina is dissected for normal plastic operations. Initially, when the posterior vaginal wall is dissected from the anterior wall of the rectum, the vagina and the rectum are densely fused in the lower third of the vagina. This fusion is seen in operations such as perineorrhaphy and posterior colporrhaphy. As the operator attempts to separate the vaginal wall, no clear plane of dissection is evident from the anterior wall of the rectum. This is the case for approximately 3 to 4 cm from the posterior fourchette. Figure 52–4 shows a dissection of the posterior vaginal wall of a cadaver. Here one can see the upper edge of this dense, connective tissue. Above this edge, one enters the middle third of the vagina. At this point, a plane of cleavage is easily created between the vaginal and rectal walls. In Figure 52–4, this is the area marked high rectocele.

When the dissection is extended above the lower third of the vagina, a natural plane of cleavage is easily created and can be dissected bluntly without difficulty to the level of the cul-de-sac (see Fig. 52–4). The layers of the middle third of the vaginal wall, when viewed microscopically, reveal differences between this middle third of the vagina and the lower and upper thirds of the vagina.

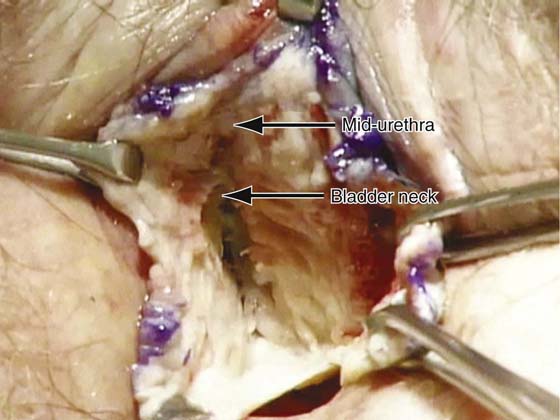

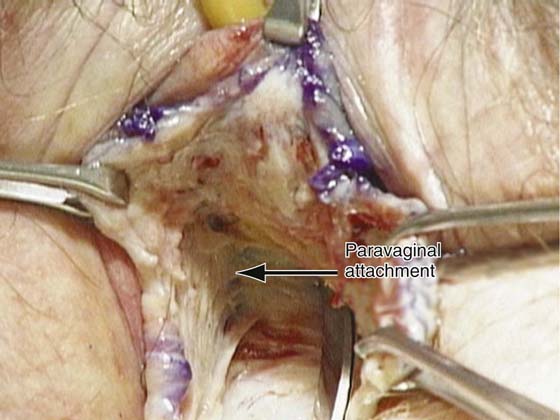

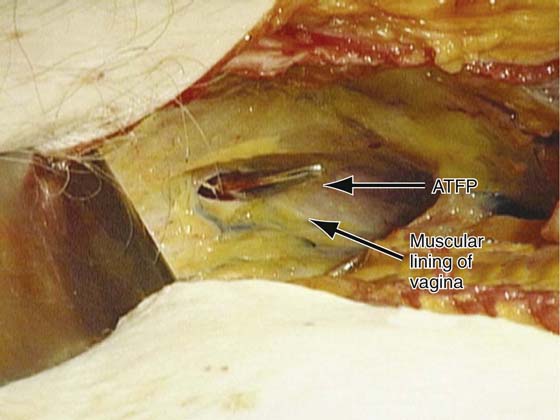

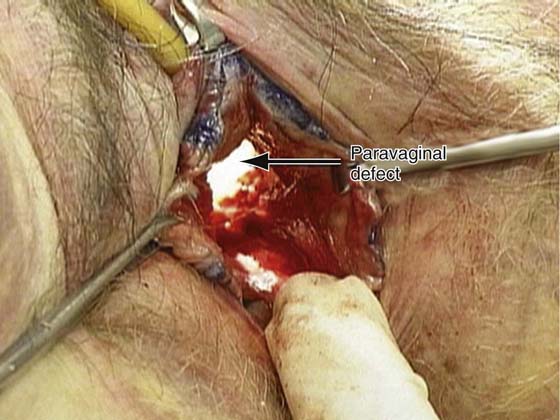

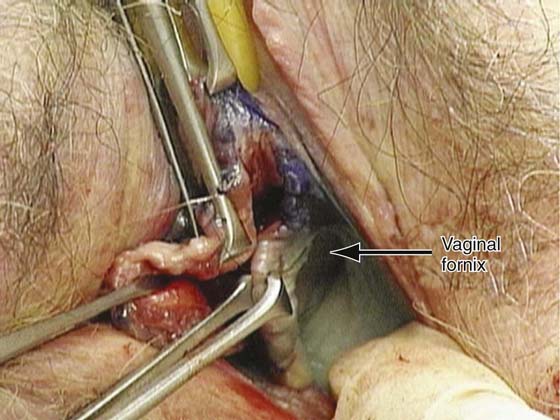

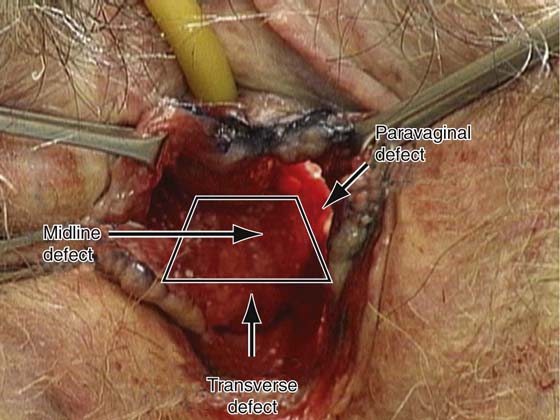

The anterior wall of the vagina shows features similar to those of the posterior vaginal wall (Fig. 52–5). The vaginal wall is densely connected to the urethra in the distal third of the vagina. After extension approximately 3 to 4 cm into the vagina, a plane of cleavage or dissection easily allows the vaginal wall to be separated from the wall of the bladder (Fig. 52–6). Analogous to the posterior vaginal walls, the fibromuscular and adventitial layers of the vagina become thinner and less well defined as one moves toward the middle of the vagina and apically toward the cervix. Laterally a dense connection is seen between the adventitial and fibromuscular layers of the vagina and the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis (Fig. 52–7). In essence, the vagina is supported by the collagen and elastic fibers found in the adventitial and fibromuscular walls of the vagina. These connective tissues are attached laterally to the fascia overlying the levator ani muscles and apically to the uterosacral and cardinal ligament complexes. Disruption to the integrity of the levator ani muscles or of the elastin collagen network of fibers in the adventitial and fibromuscular walls of the vagina will predispose the patient to anatomic defects that may commonly result in functional derangements. Figure 52–8 demonstrates the lateral attachment of the vagina viewed from the retropubic space. Note that the tip of a pair of scissors has penetrated through the attachment of the muscular lining of the vagina to the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis. Figure 52–9 demonstrates complete detachment of the lateral support of the vagina when viewed vaginally. The lateral support of the vagina should extend to the level of the arcus, which inserts in the ischial spine. This creates the vaginal fornix on each side (Fig. 52–10). Grossly, the support of the anterior vaginal wall is best viewed as a trapezoid (Fig. 52–11) that consists of a lateral attachment to the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis, a transverse attachment to the vaginal apex or cervix, and durable midline tissue.

FIGURE 52–1 Cross-sectional view of the pelvic structures. Note the relationships of vascular structures to the vagina, pelvic viscera, ureter, and coccygeus–sacrospinous ligament complex.

FIGURE 52–2 Support of the anterior vaginal wall as viewed through the retropubic space. The white area labeled as endopelvic fascia is actually the muscular lining of the inside of the vaginal wall. Note its normal attachment to the white line laterally and to the cervix or vaginal cuff proximally.

FIGURE 52–3 This drawing demonstrates the anatomy of the inner thigh and shows how these structures are related to the retropubic space and vagina.

FIGURE 52–4 Dissection of the posterior wall of the vagina on a cadaver. Note that the dense connective tissue is present only in the distal vagina. Note how the vagina and the anterior wall of the rectum are fused at this level. As the dissection extends proximally, a clear plane of dissection becomes apparent between the posterior vaginal wall and the anterior wall of the rectum that extends to the cul-de-sac. A finger in the rectum demonstrates a rectocele in the mid to upper vagina.

FIGURE 52–5 The distal portion of the anterior vaginal wall of a cadaver. Note that the area of the vagina, at this anatomic location, is fused to the posterior urethra; this is very similar to what has been mentioned previously regarding the distal portion of the posterior vaginal wall.

FIGURE 52–6 The anterior vaginal wall of the same cadaver has now been opened from the external urethra meatus all the way back to the apex of the vagina. The levels of the midurethra and bladder neck are marked. No plane of dissection is seen at the level of the midurethra because in this area the vagina is fused to the posterior urethra. As the dissection extends proximally to the bladder neck, a very clear area of cleavage between the vagina and the bladder, which extends to the inferior pubic ramus, is demonstrated.

FIGURE 52–7 This dissection has been extended farther laterally and proximally to demonstrate the normal paravaginal attachment of the anterior vaginal wall. The muscular lining of the vagina that supports the base of the bladder should extend laterally to the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis; this is the normal paravaginal attachment seen in a patient with a well-supported anterior vaginal wall.

FIGURE 52–8 A retropubic view of this anatomy is demonstrated. The muscular lining of the vagina that the base of the bladder sits on is shown, as is the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis on the right side. Note that the tip of the scissors has penetrated the urogenital diaphragm at the level of the proximal urethra or bladder neck.

FIGURE 52–9 Complete detachment of the normal attachment of the anterior vaginal wall on the right side of this cadaver.

FIGURE 52–10 Vaginal fornix of a well-supported anterior vaginal wall. The lateral attachment of the vagina proximally should attach to the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis as it inserts into the ischial spine. This normal anatomic attachment provides support and creates the lateral vaginal fornix of the anterior vaginal wall.

FIGURE 52–11 The support of the anterior vaginal wall can be viewed as having the shape of a trapezoid, where the lateral aspects of the trapezoid represent normal paravaginal support, the transverse aspects represent the normal attachment of the muscular lining of the vagina to the apex of the vagina or the anterior portion of the cervix, and the midportion of the trapezoid represents durable tissue that should prevent the base of the bladder from descending in the midline.