Anatomy of Retropubic Space

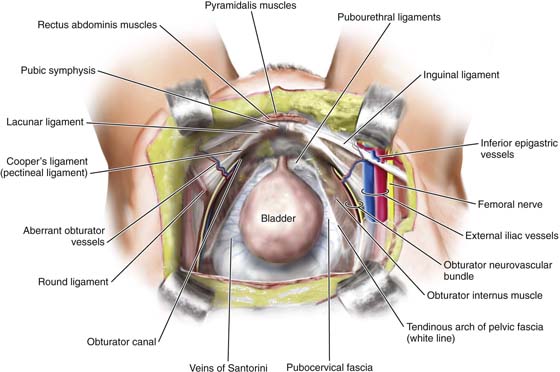

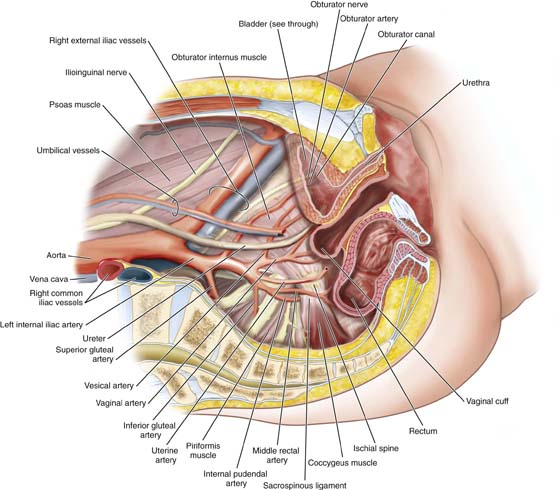

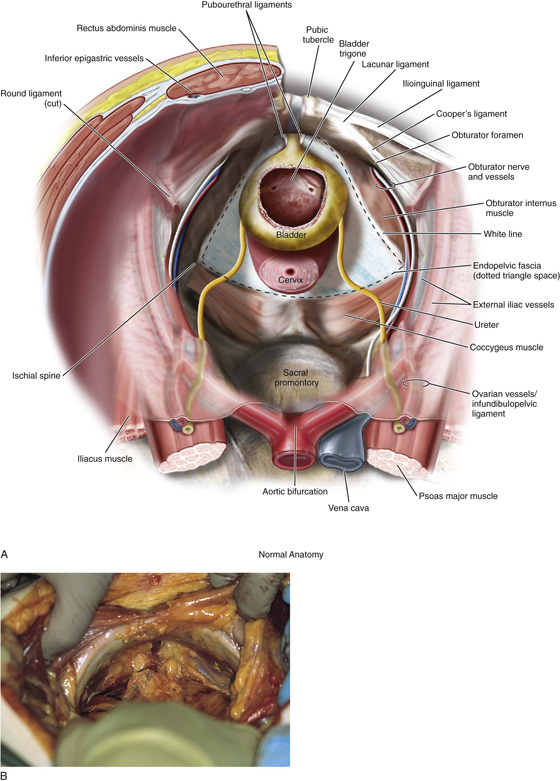

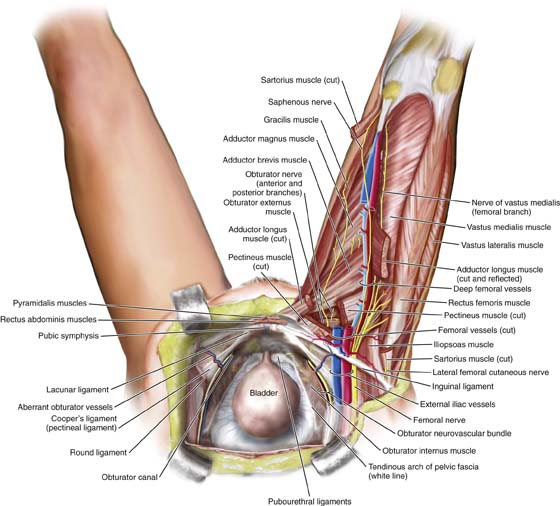

The boundaries of the retropubic space (space of Retzius) are the symphysis pubis anteriorly, the pubic rami laterally, and the sidewalls composed of pubic bone and obturator internus muscle. The anterior aspects of the proximal urethra and extraperitoneal portions of the bladder are seen upon exposure of the retropubic space. Figure 31–1 illustrates the view from above the retropubic space. Note that the floor of the retropubic space is formed by the fibrofatty outer lining of the vaginal wall termed endopelvic fascia, the perivesical fascia, and fibers from the levator ani muscle. This trapezoid structure provides support for the proximal urethra and bladder. Figure 31–2 shows a sagittal section of the normal anatomy of the pelvis. Figures 31–3, 31–4, and 31–5 demonstrate the relationship of the space to the urinary bladder, pelvic sidewall, upper thigh, and uterus.

FIGURE 31–1 Normal anatomy of the pelvis viewed from above. Note how the proximal urethra and extrapertioneal portions of the bladder are exposed through the retropubic space. Note the trapezoid-shaped endopelvic fascia or inside lining of the muscular portion of the vaginal wall. The fascia provides the support for the anterior wall.

FIGURE 31–2 Sagittal section of the normal anatomy of the pelvis. Note how the various vessels, nerves, and muscles relate to the bladder and retropubic space. Note now the external iliac vessels exit the pelvis underneath the inguinal ligament just lateral to the uppermost portion of the retropubic space, while the obturator neurovascular bundle passes through the retropubic space to exit the pelvis through the obturator canal.

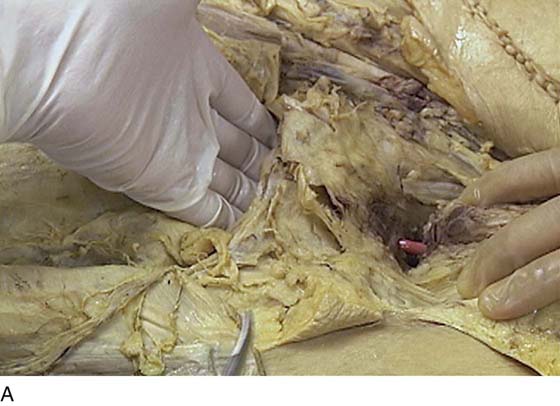

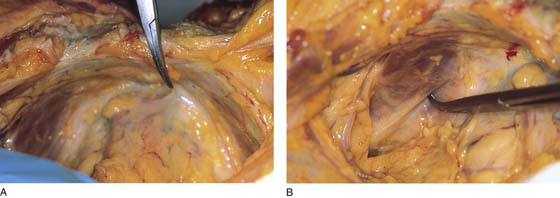

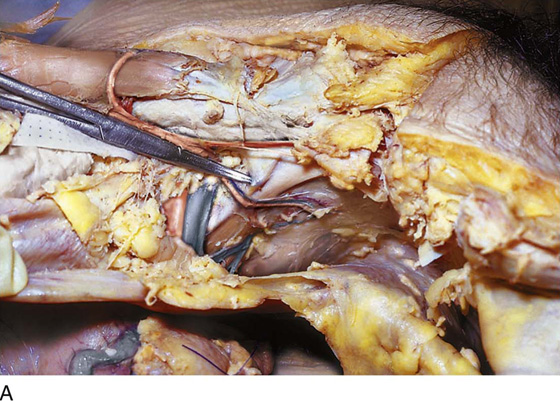

FIGURE 31–3 A. Surgical anatomy of the retropubic space. Note that the proximal urethra and bladder rest on the anterior vaginal wall with its underlying muscular component, or pubocervical fascia. The vagina attaches laterally to the white line, or arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis. The veins of Santorini run within the vaginal wall and are commonly encountered during colposuspension procedures. Other important vascular structures that may be encountered in this space include the obturator neurovascular bundle, the aberrant obturator artery and vein, and the external iliac artery and vein. B. Retropubic space in a female cadaver. Note that abundant retropubic fat is usually encountered upon initial dissection into the space.

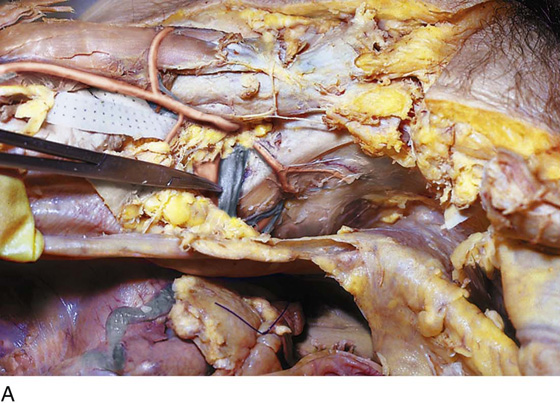

FIGURE 31–4 The uterus (U) is elevated via a fundal (blue) suture. The bladder (B) is held straight upward via a white stitch. The sawed pubic symphysis (P) is most forward (anterior). The mons veneris (M) has been cut and flapped forward anteriorly.

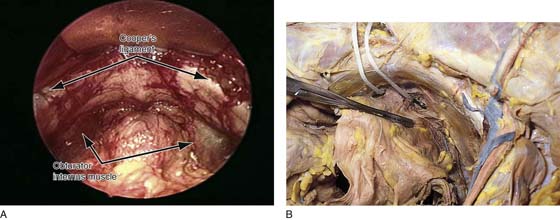

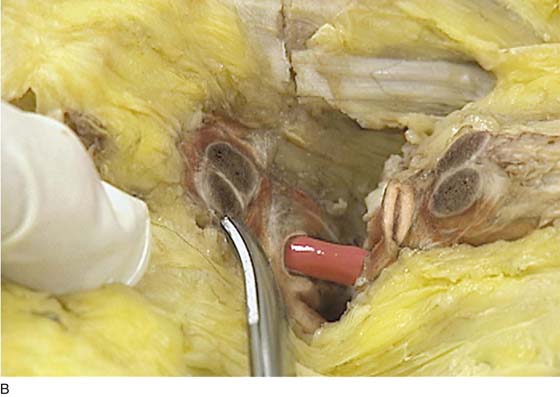

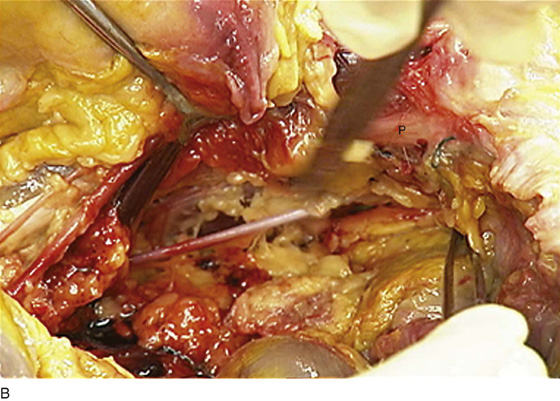

FIGURE 31–5 A. Retropubic space in a live patient. The arrows point to the top lateral portions of the space noting Cooper’s ligament. Below this, the obturator internus muscle is seen on each side. Note again the abundant retropubic fat commonly seen in this space. B. The retropubic space has been totally exposed. A large straight clamp is placed across the urinary bladder. An umbilical tape has been placed just above the urethrovesical junction. The tip of a probe placed in the vagina protrudes through the internal projection of the right anterolateral fornix.

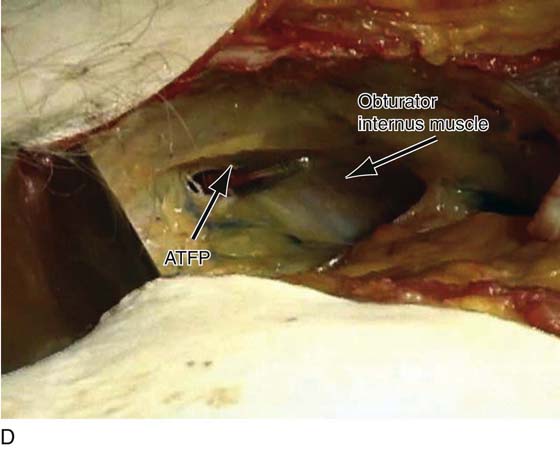

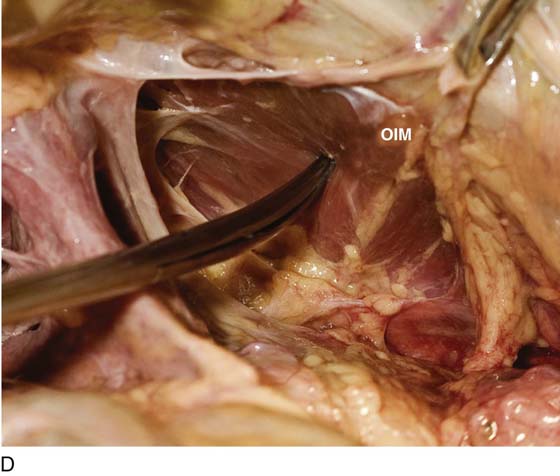

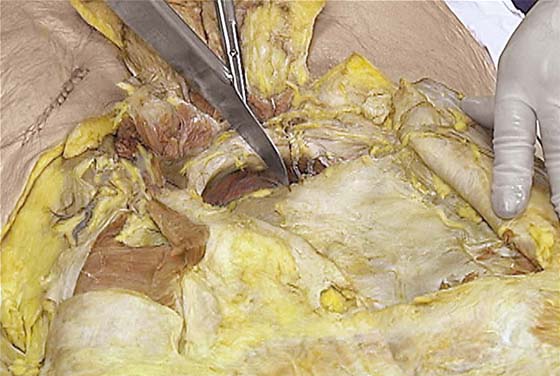

The adipose tissue behind the symphysis between the bladder and the pubic bones can be gently separated by blunt finger dissection. The space is progressively developed from the superior to the inferior margin of the pubic symphysis (see Figs. 31–4, 31–5, and 31–6). The lateral development of the retropubic space extends to the perivesical space and terminates at the pelvic sidewall or, more precisely, at the obturator internus muscle (Fig. 31–7A–C and 31–8A, B). The lateral aspects of the retropubic space are demarcated in the dissections shown in Fig. 31–9A–F. The arcus tendineus originates from the obturator internus fascia. This whitish thickening of the obturator fascia can vary in its configuration from a single line to a wishbone or double-line structure. The pubococcygeus muscle (levator ani) in turn takes its origin from the arcus tendineus. The broad levator ani funnels downward into the depths of the pelvis. A portion of the levator ani arises from the inferior margin of the pubic ramus on either side in close proximity to the urethra, where it plays a key role in the sphincter mechanism to maintain urinary continence (see Fig. 31–8A, B). At the inferior extent of the space are located the urethrovesical junction, the anterolateral vaginal fornices, and the levator ani muscles (see Figs. 31–8A, B; 31–9A, and 31–10). The urethrovesical junction and the greater mass of the urinary bladder are exposed within the space of Retzius. Specifically, these structures lie on the floor of the retropubic space (Figs. 31–11A, B and 31–12). At the level of the proximal urethra, the pubourethral (puboprostatic) ligaments are noted; these are stylized in Figure 31–3. The actual structures run from the posterior symphysis pubis to the pubocervical fascia (endopelvic fascia) in contact with the proximal urethra on each side and are thought to be key structures for the maintenance of continence (Figs. 31–13A–D). The arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis, or white line, stretches from the posterior aspect of the symphysis pubis and continues in a downward sloping direction along the fascial margin of the obturator internus muscle to terminate at the ischial spine. The attachment of the pubocervical fascia (endopelvic fascia) to the white line partially maintains the support of the lateral vaginal wall. Detachments of the pubocervical fascia from the white line will lead to paravaginal defects. The arcus tendineus can be seen clearly (see Fig. 31–9A–F). It is a fascial landmark (see Figs. 31–11 and 31–12). From the point where the levator ani takes origin from the arcus, the muscle swings downward toward the midline, thus composing a portion of the pelvic floor (see Fig. 31–8B). The levator ani muscles envelop the urethra, vagina, and rectum as the latter two (2) traverse and penetrate the diaphragm into the perineum. If the symphysis pubis is cut in the midline with a saw, the levator ani muscle can be followed inferiorly as it inserts into the lateral walls of the vagina and urethra deep to the vestibular bulb and clitoral crura.

FIGURE 31–6 Anatomy of the retropubic space as it relates to the thigh.

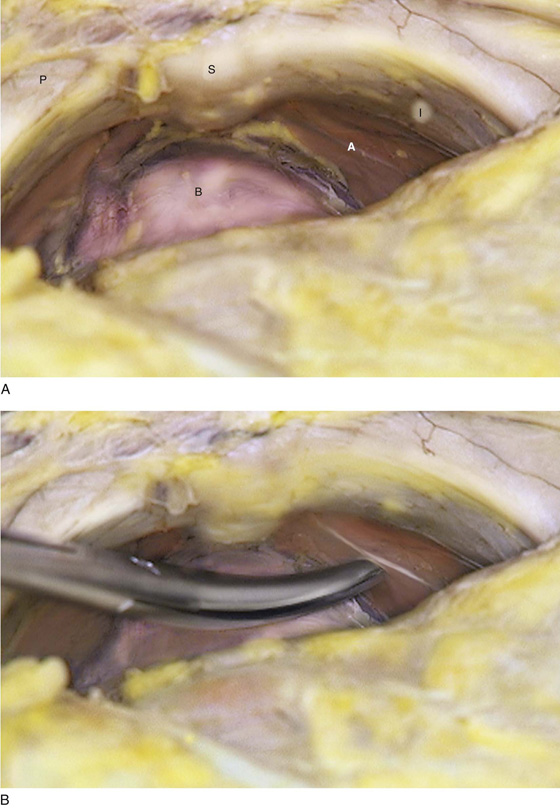

FIGURE 31–7 A. The operator’s hand lies in the retropubic space. The mons has been cut so as to create a flap that is held forward by the assistant. A red rubber catheter had been placed into the urethra. B. Detail at the point where the urethra crosses under the symphysis pubis. The scissors points to the cavernous corpora cavernosa of the clitoris. C. A gloved finger has been placed in the vagina. The vestibular bulb lies above the urethra. D. A retropubic view is a cadaver. Note that the tips of Mayo scissors have been passed through the urogenital diaphragm and are entering the right inferolateral portion of the retropubic space. This is the area that commonly is penetrated during performance of a suburethral sling procedure. The scissors penetrate the fascial attachment to the arcus lateral to the urethra and medial to the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis (ATFP). Also note the obturator internus muscle.

FIGURE 31–8 A. The entirety of the retropubic space is exposed. The symphysis (S) and pubic rami (P) occupy the anterior boundaries. The fascia of the obturator internus muscle (I) and the arcus (A) are clearly seen on the right side. The bladder (B) fills the posterior portion of the space. B. The scissors points to the white line (arcus). Below this point is the takeoff, or origin, of the levator ani muscle.

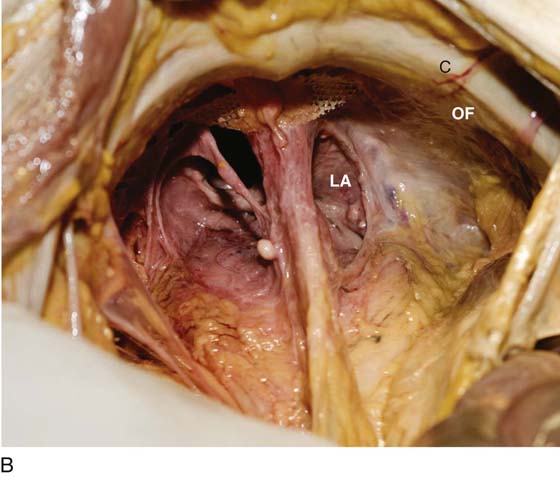

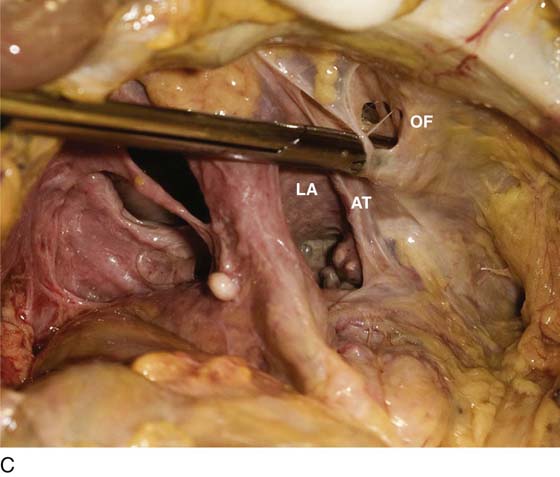

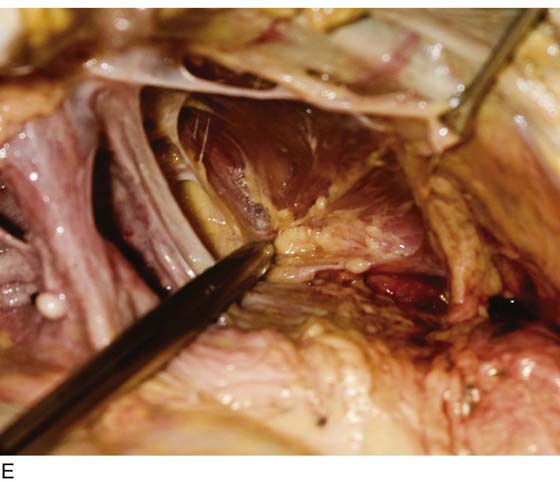

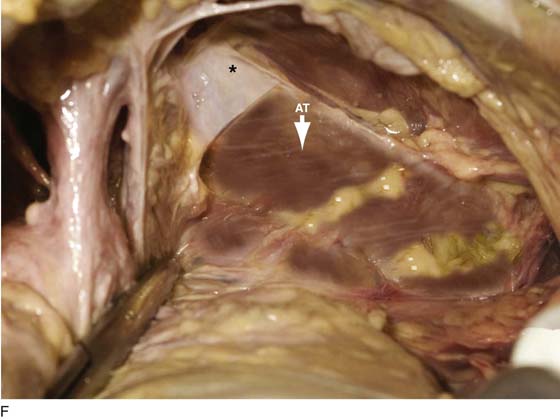

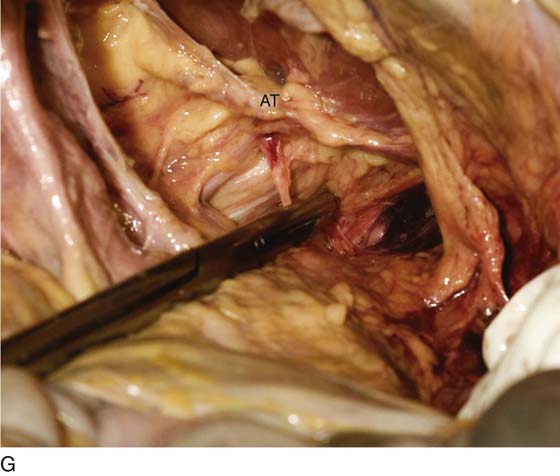

FIGURE 31–9 A. Fresh cadaver dissection exposing the retropubic space and exposure of the perivesical space. Cooper’s ligament (C) occupies a forward area on the ileopecineal line. The fascia covering the obturator internus muscle and the levator ani muscle is labeled (OF). The uterus (U) and the urinary bladder (B) are supported by the endopelvic fascia as well as by various “ligaments”. B. Close-up view of the opened retropubic space. The uterus, bladder, and proximal urethra have been excised. Cooper’s ligament is identified on the iliopectineal line of the public bones (C). The obturator fascia forms the lateral boundary of the space (OF). The margin of the levator ani (pubococcygeus) is seen (LA). C. A scissors has dissected between the obturator fascia (OF) and the underlying obturator internus muscle. The arcus tendineus is in fact formed by the obturator fascia (AT). The levator ani (LA) is clearly seen beneath the arcus tendineus. D. The obturator fascia has been removed. The scissor tip points to the obturator internus muscle (OIM). E. The scissors depresses the arcus tendineus. F. The levator ani (pubococcygeus) is exposed as it sweeps downward into the depths of the pelvis (at the arrow). Note the muscle(s) originates from the arcus tendineus (AT). The obturator internus muscle lies above the white line (AT). The asterisk marks the remnant of the fascia that overlies the levator ani muscle (superior fascia LA). G. The white line (arcus tendineus) terminates 2 cm distal at the ischial spine (dark space). The slop of the arcus is a smooth line from its superficial point downwards and deep.

FIGURE 31–10 The pubic bone is being sawed to expose the structures passing beneath the symphysis.

FIGURE 31–11 A. Fresh cadaver dissection exposing right and left white lines. The clamp tip is located just to the right of the symphysis pubis. B. Close-up detail of the left obturator internus muscle above the arcus tendineus (tip of clamp).

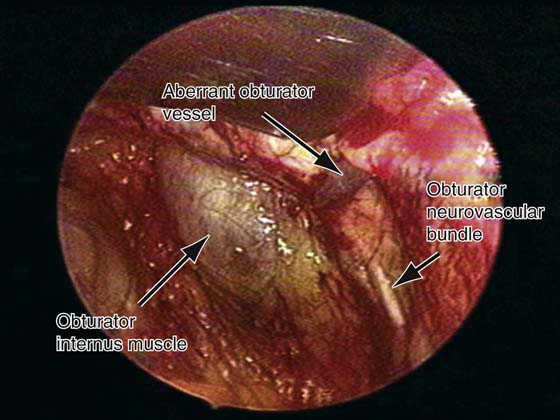

FIGURE 31–12 Laparoscopic view of the right sidewall of the retropubic space in a live patient. Note the aberrant obturator vessel seen draping over Cooper’s ligament. Also note the obturator neurovascular bundle as it exits the pelvis through the obturator canal and the obturator internus muscle with its overlying fascia.

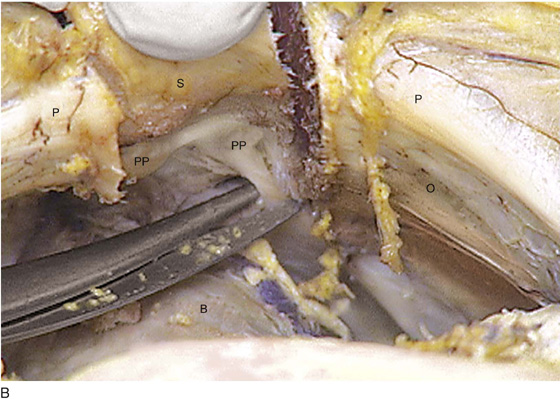

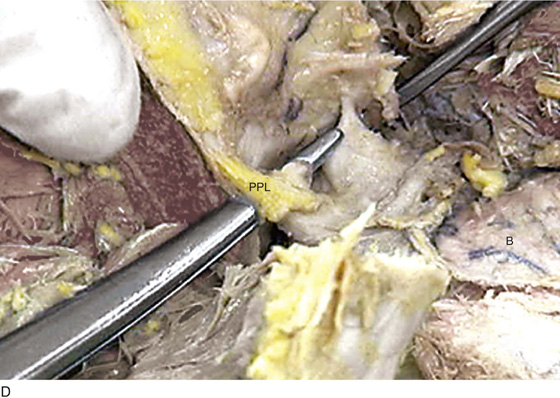

FIGURE 31–13 A. The scissors is placed just beneath the arcus tendineus. The operator’s thumb pressed the sawed symphysis forward. The arcus leads directly to the posterior puboprostatic (pubourethral) ligaments. The urethra (U) passes beneath the posterior margin of the symphysis, and the obturator internus muscle (O) makes up the pelvic sidewall. Cooper’s ligament (C) and the bladder dome (B) are labeled. B. The blade of the scissors tenses the right posterior puboprostatic ligament (PP) attached to the urethra at its junction with the bladder. The obturator fascia (O) lies below the pubic rami (P). C. The sawed symphysis (S) is pushed farther forward. The clamp tip is under the left puboprostatic ligament, bladder (B), and pubic bone (P). D. Close-up of Figure 31–13C: puboprostatic ligament (PPL) and bladder (B).

A ridge of bone and ligamentous tissue is observed just beneath the superior margin of the superior pubic ramus. These are the iliopectineal line and Cooper’s ligament, respectively (Fig. 31–14). As the dissection of the superior pubic ramus continues laterally and posteriorly, the external iliac artery and vein are identified as they pass under the inguinal ligament and into the thigh to become the femoral artery and vein (Fig. 31–15A, B). Other important vascular structures in this space include the veins of Santorini (see Fig. 31–3), which run within the vaginal wall at right angles to the sidewall, as well as the obturator neurovascular bundle, which exits the pelvis through the obturator foramen (Figs. 31–15C and 31–16A, B). Frequently an anomalous vessel crosses the pubic bone just forward of the external iliac vessels. This is known as the aberrant, or anomalous, obturator artery and vein (Fig. 31–17). Injury to these vessels can result in heavy bleeding when a Burch urethropexy is performed. Special care must be taken to avoid vascular injury during retraction of the anterior abdominal wall to expose Cooper’s ligament at the time of retropubic urethropexy.

The vagina, bladder, and urethra are supported as a unit by structures within the retropubic space. As noted, these structures share some connective tissue walls (Fig. 31–18A, B). Perivesical and perivaginal fascial structures provide the major pelvic support for the upper vagina and bladder base. Clearly, the most impressive and concretely defined support is the deep parametrium (i.e., the deep cardinal ligament [pictured in Fig. 31–19A]). More pictures and discussion relative to upper vaginal support are included in Chapter 51 (“Anatomy of the Vagina”). The deep cardinal ligament attaches to the pelvic sidewall in an arcing fashion and more specifically attaches to the obturator internus fascia deep within the retropubic space (Fig. 31–20A–C).

Injuries to the structures constituting the natural support of the bladder and urethra, including the endopelvic fascia, levator ani muscles (including the investing fascia enveloping these muscles), perivesical fascia, puboprostatic (pubourethral) ligaments, and deep parametrium, will result in recognizable defects. The most notable of these tissue injuries results in the creation of a cystourethrocele. Atrophy and diminution of vascular structures around and within the proximal urethra in conjunction with the above defects will lead to urinary incontinence.

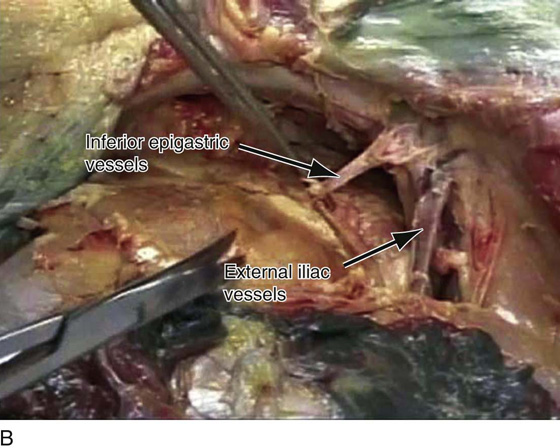

FIGURE 31–14 A. The connective tissue has been cleaned away from the left superior pubic ramus. The clamp has been inserted into Cooper’s ligament. Note the skin and hair of the mons in the upper right quadrant. B. Note the lowest portion of the external iliac vessels. Also noted are the inferior epigastric vessels as they rise from the external iliac vessels and pass in a cephalad direction. C. A close-up view of the external iliac vessels and origin of the inferior epigastric vessels. Also seen is the obturator neurovascular bundle as it passes through the retropubic space.

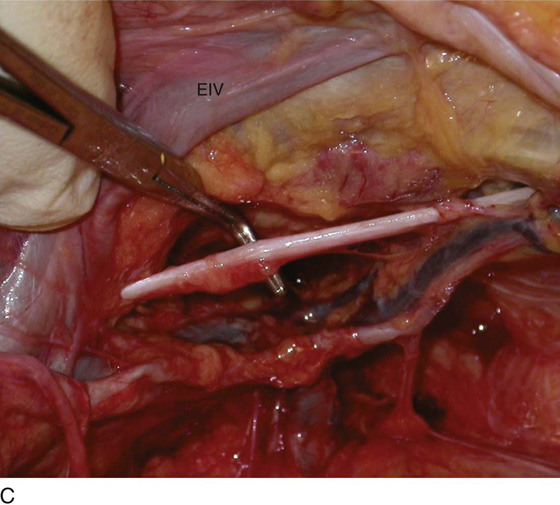

FIGURE 31–15 A. The lateral and posterior portions of the pubic ramus are crossed by the external iliac vessels. The clamp points to the external iliac vein. B. The left external iliac vein is held via a vein retractor. The pubic ramus (P) has been dissected clear of fat. The obturator nerve is seen crossing the retropubic space. C. The right-angle clamp tenses the left obturator nerve. The nerve and artery can be seen entering the short obturator canal beneath the left pubic ramus. The external iliac vein (EIV) is seen crossing over the ramus laterally. D. A cadaveric dissection notes the origin of the inferior epigastric vessels from the right external iliac.

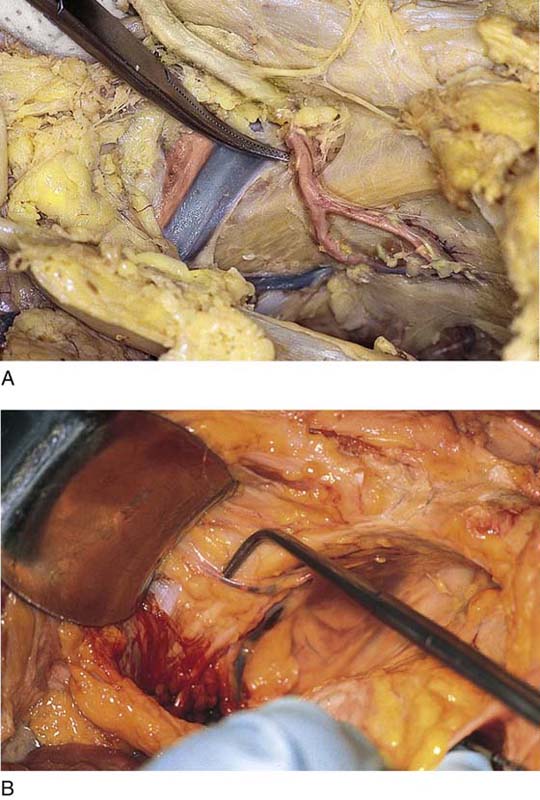

FIGURE 31–16 The external iliac artery (ei) and vein are crossing over the pubic bone (P) into the thigh. The forceps grasps the obturator nerve, which is exiting the retropubic space via the obturator foramen. B. Close-up view of Figure 31–16A. The tip of the scissors is poking into the obturator foramen. Immediately above is the pubic ramus (P) covered in Cooper’s ligament (pink).

FIGURE 31–17 A. Not infrequently, an anomalous obturator vessel will cross the lateral superior pubic ramus and the iliopectineal line. Inadvertent severing of this vessel results in heavy bleeding that is difficult to control because the artery retracts. Note that the direction of a potential retraction intersects with the course of the external iliac vein. B. Still another variation of anomalous obturator vessels is located just above the right-angle clamp. A small portion of the left external iliac vein is seen beneath the edge of the retractor blade.

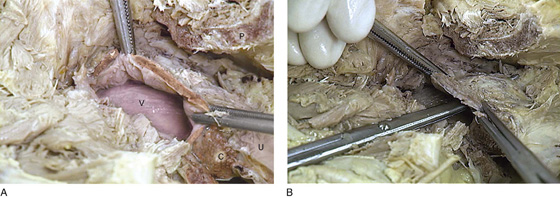

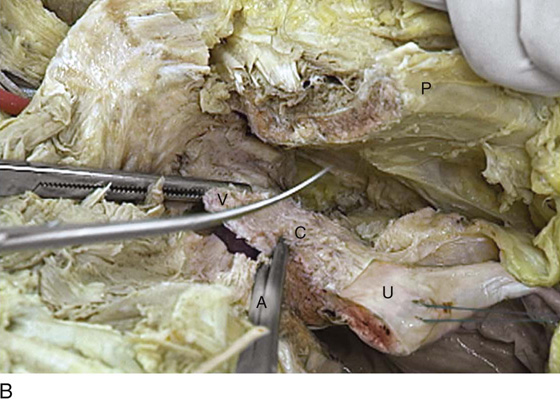

FIGURE 31–18 A. Beneath the sawed out pubic symphysis (P), the bladder (with the exception of the base) has been cut away to expose the upper vagina (V). The cut edges (anterior wall) are held by Kocher clamps. Sagittal sections of the cervix (C) and uterus (U) are seen to the lower right. B. A long scissors had pierced the lateral vaginal fornix. Note that it enters the retropubic space.

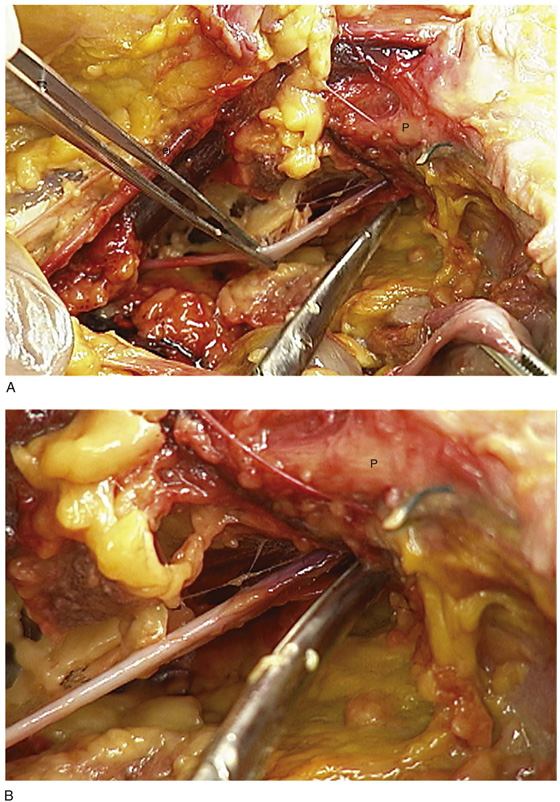

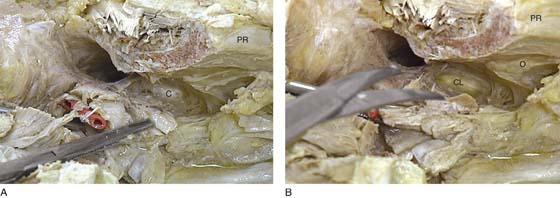

FIGURES 31–19 A. The anterior urethral wall has been cut open. The bladder base and the posterior wall of the urethra are densely attached to the anterior vagina. The perivesical and perivaginal support consists most notably of the deep cardinal ligament (C), which arcs back and attaches to the obturator internus fascia. Note the pubic ramus (PR) above. B. The scissor is poised to cut the deep parametrium (cardinal ligament) (CL). After this ligament, the unit consisting of the vagina, urethra, and bladder is virtually free and can be easily mobilized. Note the pubic ramus (PR) and the obturator internus muscle (O).

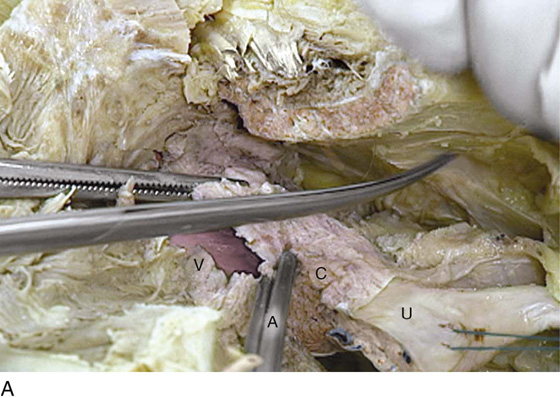

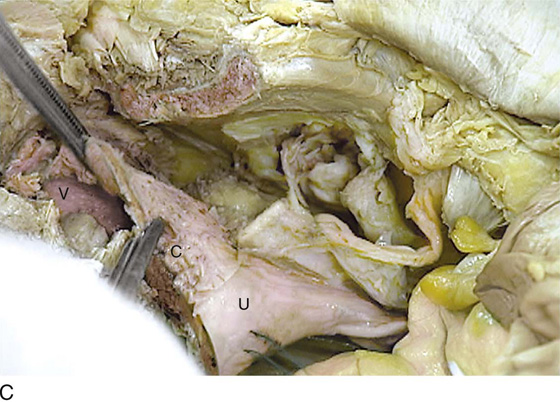

FIGURE 31–20 A. The scissors points to the obturator internus muscle. The Kocher clamps hold the cut anterior vaginal wall. The opened vagina (V) is visible. The hemisected cervix (C) and uterus (U) attach to the vagina at the Kocher clamp. The fundus of the uterus is held by a Vicryl (blue) suture. B. Similar view to Figure 31–17A, but taken in the panoramic mode. The pubic bone (P) is cut. The scissors rests on the fascia of the obturator internus muscle (I). The vagina (V) is attached to the hemisected cervix (C) and uterus (U). C. View from above the retropubic space. The bladder and urethra have been cut out. Also, the deep cardinal ligament has been incised. The cervix (C), uterus (U), and vagina (V) are the only major structures left. Note their relationship to the pubic bone (P) and the missing symphysis pubis.

Mickey M. Karram

Mickey M. Karram