Anatomy of the Retroperitoneum and the Presacral Space

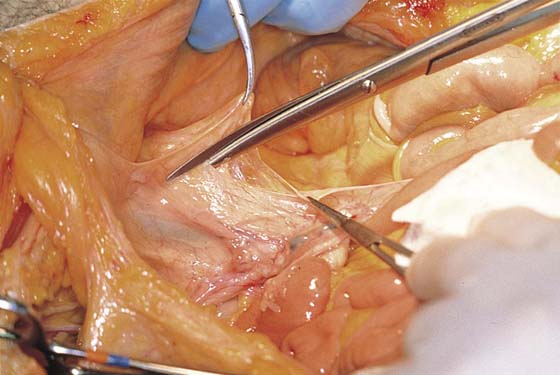

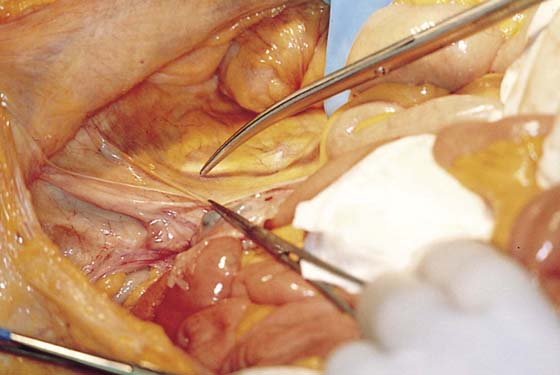

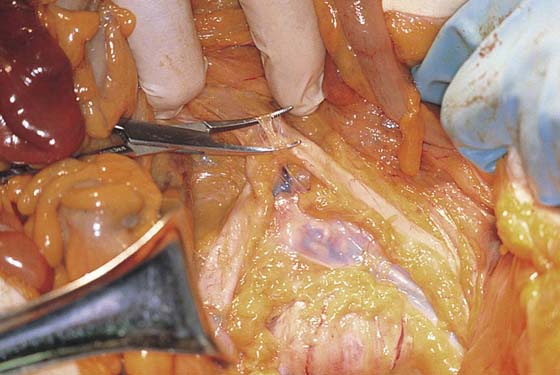

The retroperitoneal space may be entered at several points in a safe and easy manner. The broad ligament may be entered by grasping and tenting up the round ligament. The ligament may be suture-ligated and cut, or simply grasped in a clamp. The peritoneum posterior to the ligament is cut vertically back in the direction of the ovarian vessels and ureter. The author recommends always first palpating the pulse of the external iliac artery and always opening lateral to that vessel over the psoas major muscle. The muscle is identified (as is the genitofemoral nerve). Next, the external iliac artery is identified just medial to the muscle edge (Figs. 36–1 through 36–4).

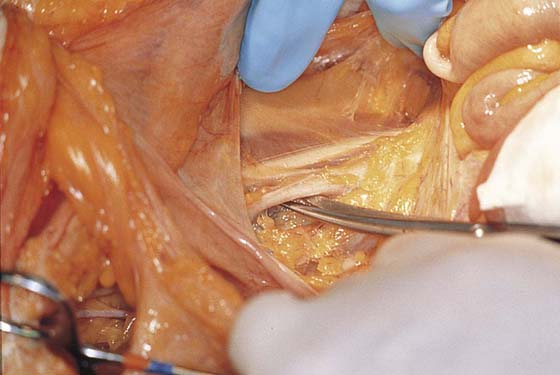

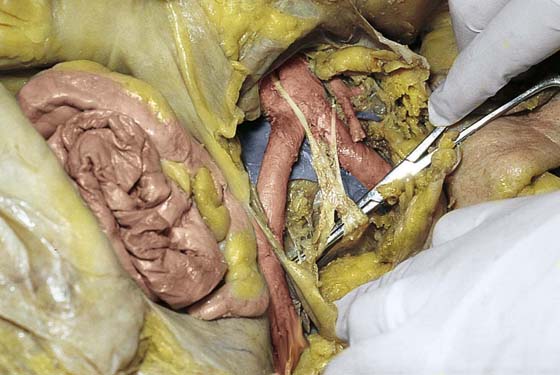

The sigmoid colon joins the rectum posterior to the uterus. Above this junction, the sigmoid proceeds upward and swings to the left, where it is attached to the peritoneum reflected over the psoas major muscle and iliacus muscle. This is not an adhesion but rather a normal physiologic attachment and corresponds to the area beneath the peritoneum where the left ovarian artery and veins, as well as the left ureter, are located. This is the general area where these structures cross the left common iliac artery. Cutting the peritoneum over the psoas muscle and reflecting the colon medially represents still another method of safely gaining entry into the left retroperitoneum. Further extending the cut into the broad ligament opens the retroperitoneal space wider and permits an excellent view of the course of the ureter (Figs. 36–5 through 36–9).

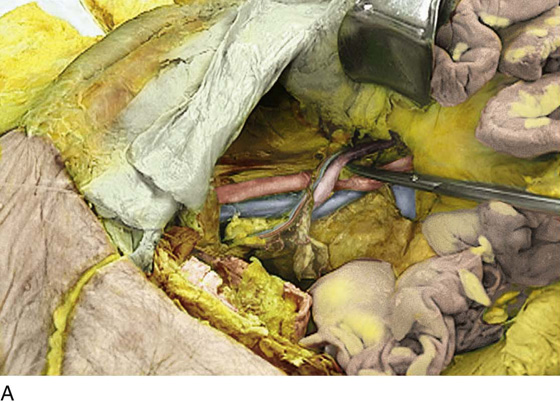

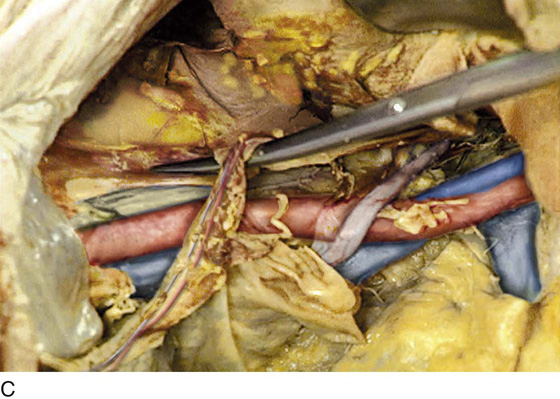

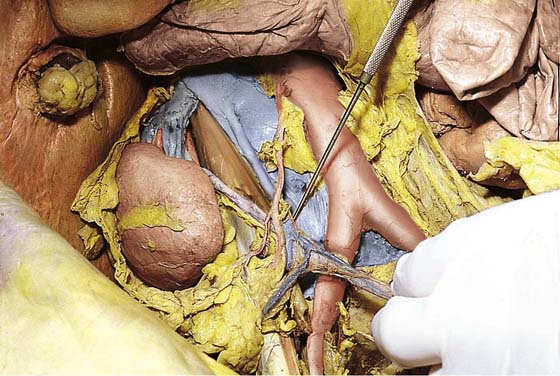

The peritoneal incision and dissection proceed superiorly (upward), extending from the round ligament over the psoas muscle and the external iliac artery. The uterus is pulled sharply to the left or right side of the pelvis. This places the structures to be identified on traction. The ovarian vessels and ureter are identified as they cross over the common iliac artery (Figs. 36–10 through 36–12). Immediately posterior to (beneath) the external iliac artery is the large (bluish) external iliac vein. This thin-walled vessel follows a course identical to that of the external iliac artery. Retracting the vein and removing or pushing aside the fatty tissue surrounding the vessel brings into view the obturator internus muscle. This muscle is often referred to as the pelvic sidewall (Fig. 36–13).

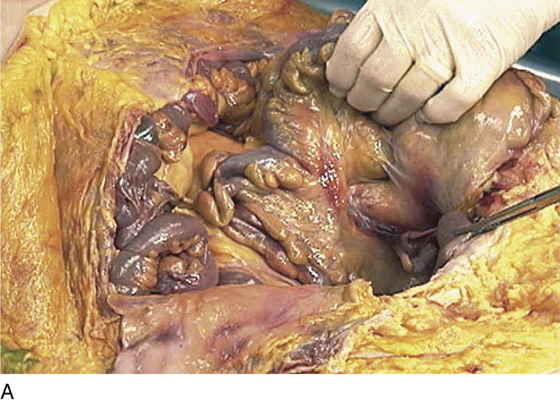

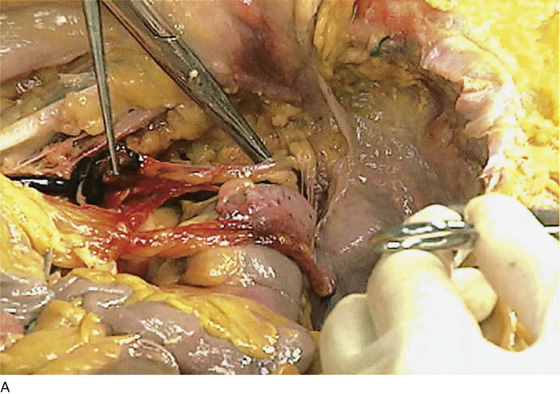

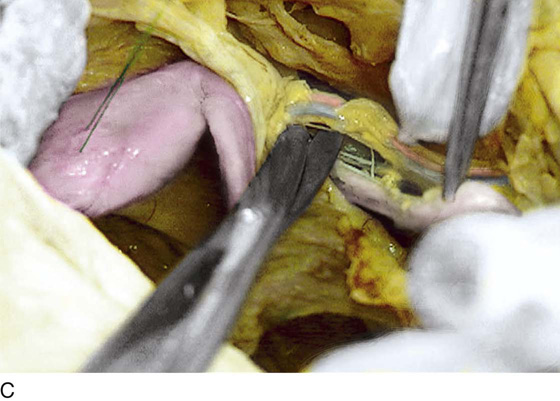

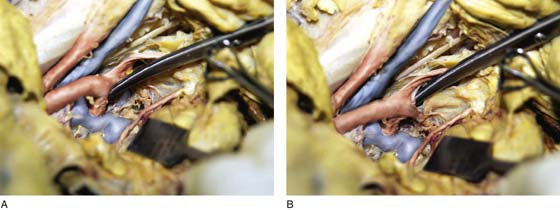

Entry into the presacral space may be achieved by pulling the rectosigmoid to the left side of the pelvis and incising the peritoneum vertically just to the right side of the sigmoid peritoneal attachment to the posterior pelvis (Fig. 36–14). This dissection will begin at the aortic bifurcation and will proceed inferiorly over the presacral space (Figs. 36–15 and 36–16A, B).

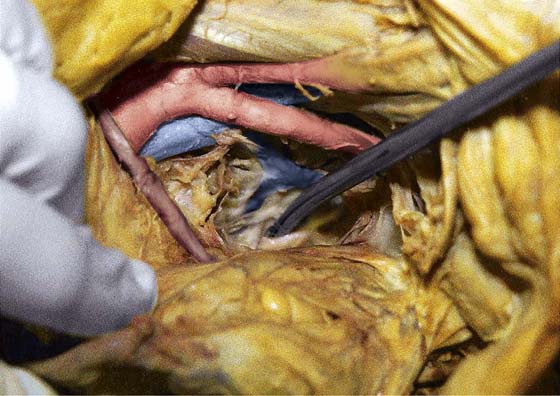

The most vulnerable structure exposed to real or potential injury in this location is the left common iliac vein, which crosses the sacral promontory from left to right. It must be identified immediately (Figs. 36–17 and 36–18).

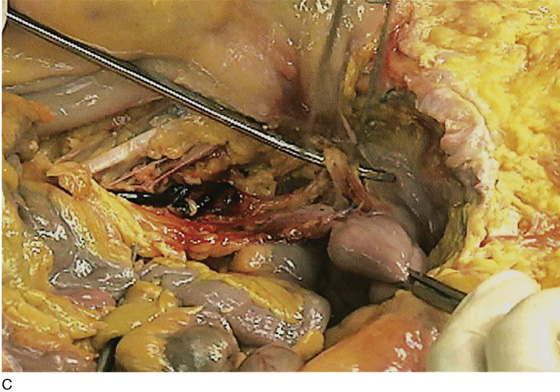

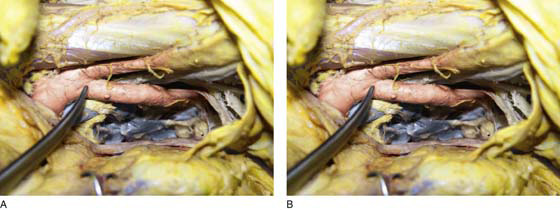

The middle sacral vessels and the middle hypogastric plexus are identified descending over the sacrum into the depths of the sacral hollow. The vessels emerge beneath the left common iliac vein, whereas the nerves cross over the vein (Fig. 36–19A–G).

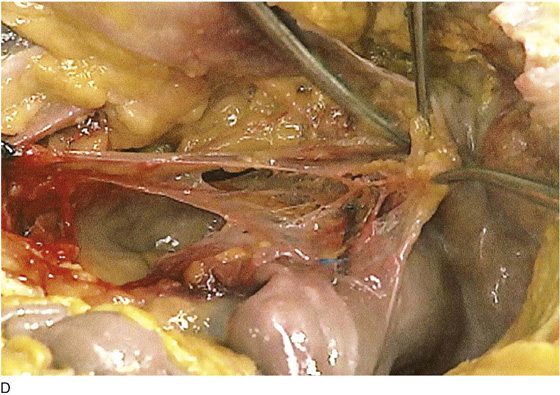

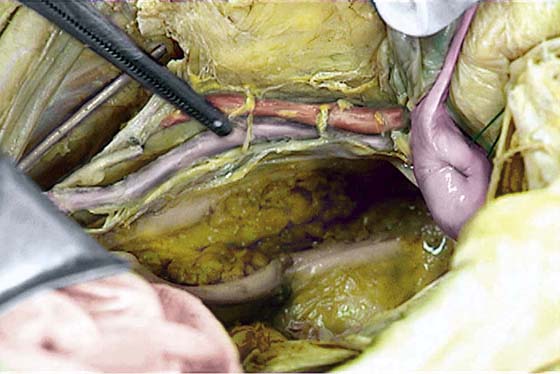

The hypogastric nerve plexus descends into the pelvis over the anterior surface of the aorta and enters the presacral space between the iliac arteries. The plexus crosses over the left common iliac vein and lies anterior to the middle sacral vessels (Figs. 36–19 through 36–21). To the left and lateral lie the inferior mesenteric artery and its branches (Fig. 36–22). To the right and lateral lies the right ureter (see Fig. 36–22). If one were to extend the dissection above the pelvis and broaden the exposure laterally, the ureters would lead the dissector to the kidney, the ovarian arteries to the aorta, and the ovarian veins to the vena cava and left renal vein (Figs. 36–23 and 36–24).

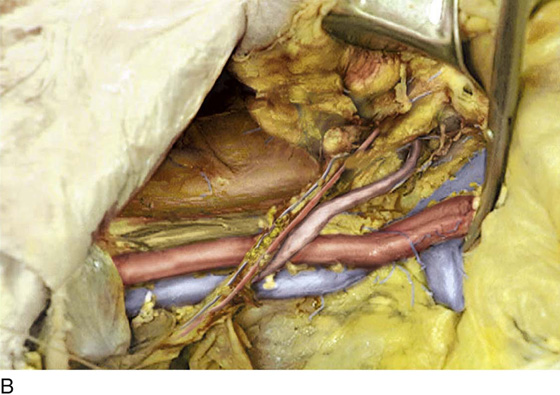

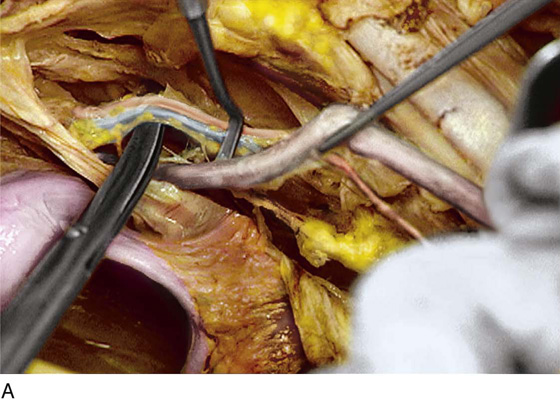

The common iliac artery bifurcation is an excellent point of reference to ensure differentiation between the external and internal (hypogastric) iliac arteries (Fig. 36–25A, B). The pelvic ureter is always medial to the internal iliac artery (Fig. 36–26). The internal iliac artery itself quickly divides into two sections (anterior and posterior) (Fig. 36–27A, B). Of particular importance are the numerous and frequently anomalous pelvic veins lying posterior and deep to the internal iliac artery (Fig. 36–28). If one were to follow the posterior division of the hypogastric artery into the depths of the pelvis and through the treacherous venous field to the area of the ischial spine and the lateral edge of the sacrum, large sacral nerve roots would be encountered (Fig. 36–29).

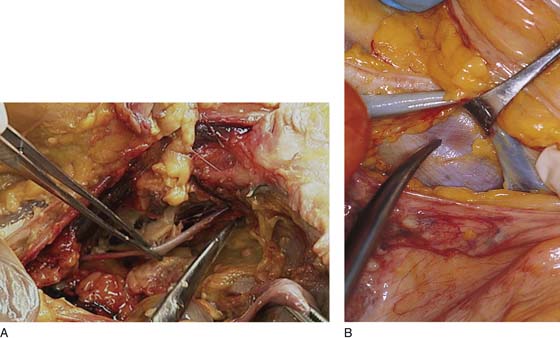

FIGURE 36–1 The retroperitoneal space may be entered by elevating the peritoneum at the top of the broad ligament between the round and infundibulopelvic ligaments. The peritoneum is incised and opened parallel to the psoas major muscle. This dissection is performed on the right side.

FIGURE 36–2 The medial edge of the opened peritoneum is held with a forceps. The tip of the scissors points to the medial margin of the right psoas major muscle.

FIGURE 36–3 The fat has been cleared away from the right psoas major muscle, and the tip of the scissors rests on the belly of the muscle.

FIGURE 36–4 The right external iliac artery has been identified just medial and slightly inferior to the psoas major muscle. The spread scissors are under the artery.

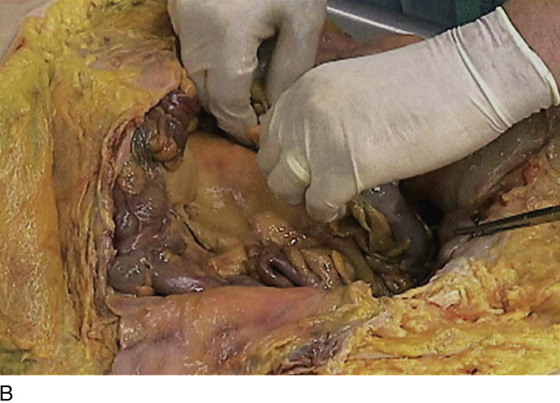

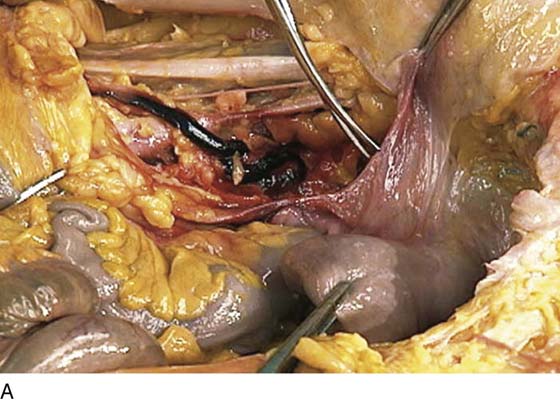

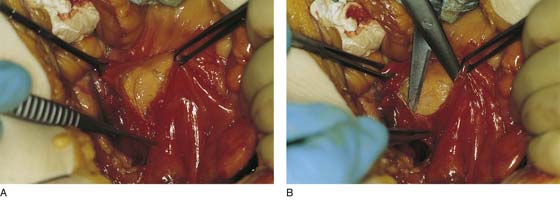

FIGURE 36–5 A. The sigmoid has been pulled out of the pelvis. Note the extension of the infundibulopelvic ligament toward the root of the sigmoid mesentery. The colon covers the uterus and left adnexa in its in situ position. The mesentery of the colon is exposed and reveals that the sigmoid colon is an intraperitoneal structure. The sigmoid colon initially lies to the left of the midline. The S configuration can be seen here as well. The colon swings to the right and joins the rectum posterior to the uterus (held up in the Kocher clamp). B. This view shows the somewhat redundant sigmoid colon covering the left adnexa. The uterus can be seen because it is being pulled forward and upward by the applied clamp. C. The sigmoid colon is pulled to the right, exposing the attachments to the laterally disposed parietal peritoneum. This is a very convenient location from which to enter the left retroperitoneal space.

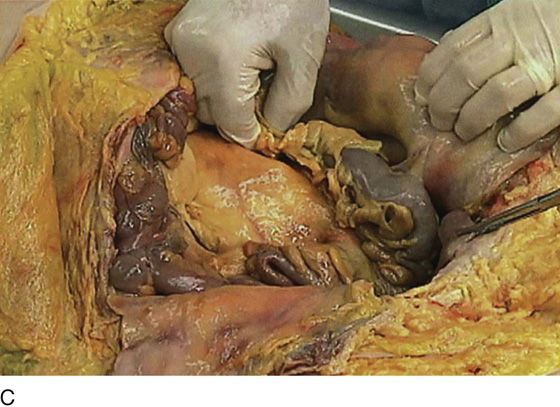

FIGURE 36–6 A. The peritoneal attachments of the sigmoid colon have been cut, allowing the large bowel to be mobilized to the right. The attachments of the lower portion of the descending colon are about to be cut. B. The left retroperitoneal space has been opened lateral to the point where the ovarian vessels and ureter enter the pelvis. The psoas major muscle is seen vectoring at a 90° angle to the sigmoid colon.

FIGURE 36–7 A. Detail of the left retroperitoneal space. The clamp holds the left oviduct and the left ovary. The forceps holds the ovarian blood supply (infundibulopelvic ligament). The ureter (unseen) lies immediately posterior to the ovarian vessels. The psoas major muscle is seen in the background. The genitofemoral nerves (on the psoas) can be seen posterior to the tendon of the psoas minor muscle. B. This dissection has been carried lateral to the psoas major muscle and to the iliacus muscle. The scissors elevate the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve.

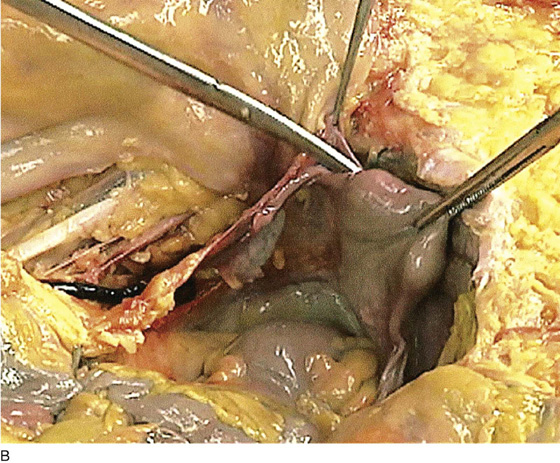

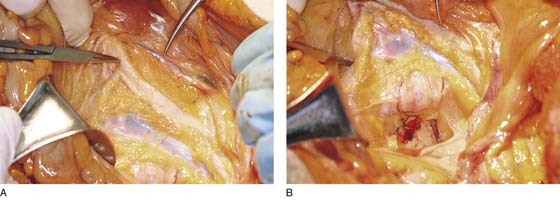

FIGURE 36–8 A. The uterus has been grasped with a Kocher clamp and pulled upward and to the right. The broad ligament on the left is held upward on tension. The scissors will cut the broad ligament to further expose the left retroperitoneal space. The ureter has been dissected from the ovarian vessels. A thrombosed supply vessel marks the ureter. In the background are the external iliac artery, the genitofemoral nerve, and the psoas major muscle. B. The broad ligament has been cut. The uterovesicle peritoneum is being incised. The entire left retroperitoneal space is opened. The sigmoid-rectal junction is behind the cervix and posterior vagina. The cul-de-sac is filled with redundant colon. C. The sigmoid colon is pulled out of the cul-de-sac, exposing the entire cul-de-sac. Note the more prominent left uterosacral ligament.

FIGURE 36–9 A. A length of ureter is shown. Proximally, the ureter is held with forceps (at the termination of the thrombosed feeding vessel). Distally, the scissors are slipped under the ureter at the point where the uterine vessels cross over it. B. The uterine vessels are tented-up by the forceps. The scissors tip begins to dissect them free of the ureter. The surgeon’s gloved finger points to the uterine fundus. C. The uterine vessels have been dissected free from the underlying ureter. The scissor tip rests on the urinary bladder. The Kocher clamp applies traction to the uterus. D. Close-up view of the ureter entering the bladder. The uterine vessels have been cut. The near (right) tonsil clamp holds half of the severed vessels. The scissors are dissecting the bladder wall.

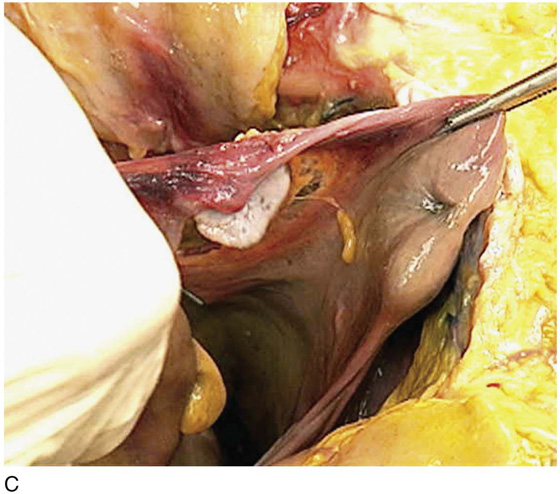

FIGURE 36–10 A. The right retroperitoneal space has been opened by cutting the peritoneal attachments of the cecum and ascending colon. The ureter (posterior and medial) descends into the pelvis with the ovarian vessels over the common iliac artery. B. The ovarian vessels are stretched. The ureter lies medial to the infundibulopelvic ligament and slightly posterior to it. The scissors rest on the left common iliac vein. The ureteral crossover is slightly caudad to the iliac artery bifurcation. C. Close-up view of the ovarian vessels, which are held upward by the scissors. The ureter crossover is seen medial and posterior to the ovarian vessel crossover. The ovarian vessels have been artificially advanced forward.

FIGURE 36–11 A. Close-up dissection of the right ureter as it crosses beneath the right ovarian artery (held upward by the scissors). The ureter is held by the forceps and is pointed to by the right-angle probe. The uterus lies in front of the scissors shaft, and the right uterosacral ligament is below the shaft. B. Close-up view of the ureter crossing under the right uterine vessels. C. The scissors are spread under the uterine artery. The stitch places traction on the uterus. The adnexa are retracted beneath the blades of the scissors. D. The clamp points to the ovarian vessels as they enter the retroperitoneum beneath the peritoneum and at the root of the ileocecal mesentery. The cecum is above. The uterine fundus is (sutured) to the far left. E. The right retroperitoneum has been opened. The ureter has been dissected free from the ovarian vessels. The ureter crosses over and lies medial to the right iliac artery bifurcation. The clamp points to the right common iliac artery.

FIGURE 36–12 The blue-tinged left uterine artery is shown. The adnexa are retracted out of the picture. The clamp points to the left ureter. The ovarian vessels have been cut.

FIGURE 36–13 A. The obturator space (fossa) has been dissected. The left obturator nerve is held by the forceps. The external iliac artery and vein are seen above. B. The external iliac vein is retracted to show the upper margin of the obturator internus muscle.

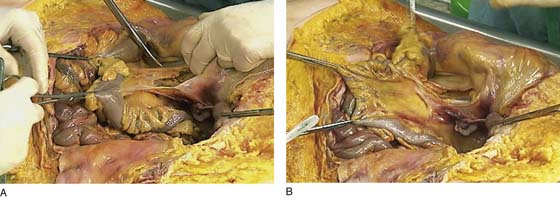

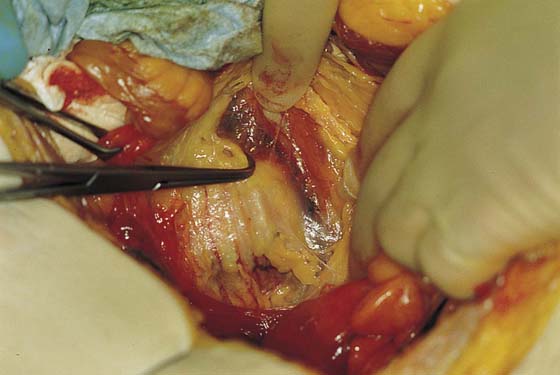

FIGURE 36–14 The sigmoid colon has been retracted to the right. The peritoneum overlying the sacrum and aortic bifurcation is elevated and incised.

FIGURE 36–15 A. The edges of the peritoneum are held with two Allis clamps. The presacral space is opened, exposing the underlying properitoneal fat. B. The dissecting scissors carefully expose the underlying sacral bone, middle sacral vessels, and hypogastric nerve trunks.

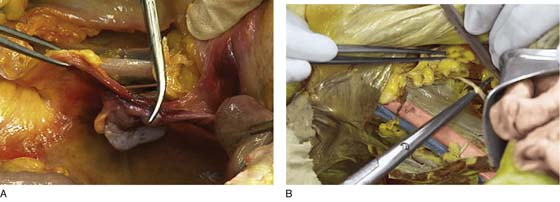

FIGURE 36–16 A. The straight clamp points to the aorta. Below the bifurcation, the left common iliac vein can be seen extending from the left to the right side of the pelvis. The scissors point to the left ovarian vascular pedicle. B. The sacral promontory and the presacral space are exposed.

FIGURE 36–17 A tonsil clamp dissects the presacral space. The tip of the clamp points to the left common iliac vein where it crosses the sacrum from left to right.

FIGURE 36–18 The right common iliac artery is elevated with scissors to show the left common iliac vein crossing under it.

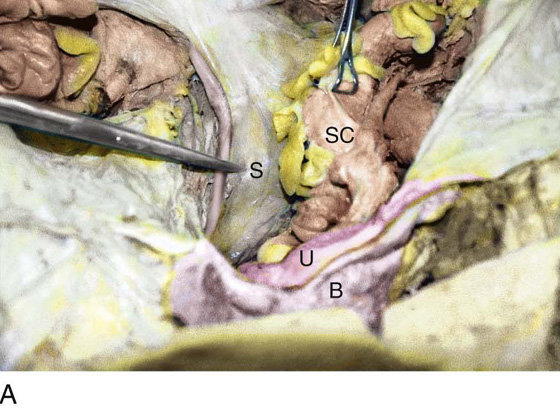

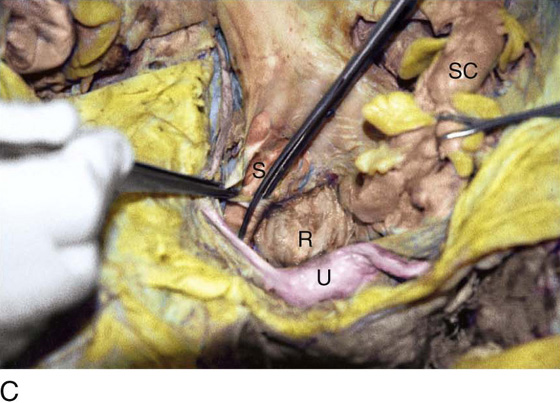

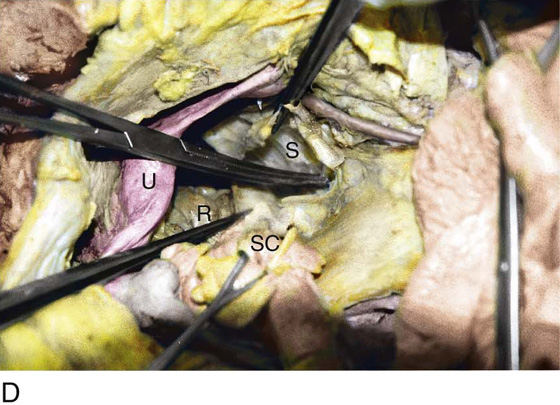

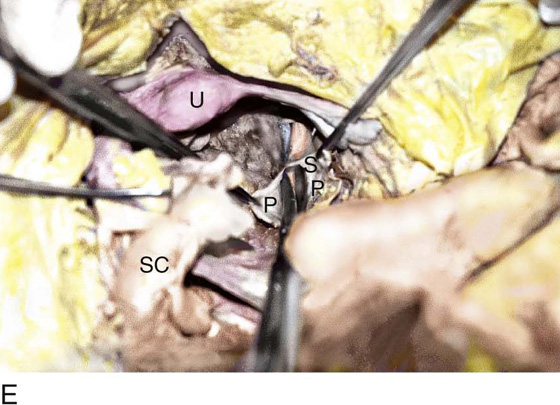

FIGURE 36–19 A. The lower part of the sigmoid colon (SC) is pulled to the left. The scissors lie on the posterior parietal peritoneum, which in turn overlies the sacral bone (S). Note the dissected right ureter crossing beneath the closed blades of the scissors. The uterus (U) and bladder (B) are seen in the foreground. B. The entire presacral space has been opened up. The scissors point to the left common iliac vein, which sweeps across the L5 vertebral body. Above (cranial to) the left common iliac vein is the aortic bifurcation. The angled probe rests on the right external iliac artery. C. The peritoneum overlying the sacrum (S) is opened by means of long Metzenbaum scissors. The sigmoid colon (SC) is pulled to the left. The rectum (R) is to the left of the lower extent of the intended peritoneal incision. The uterus (U) is in the foreground. Note the right ureter crossing beneath the forceps. D. The overhead photo shows the relationships of the uterus (U), the rectum (R), the sigmoid colon (SC), and the presacral space. The curved clamp points to the sacral promontory (sacral vertebral body one). The peritoneum overlying the presacral space has been cut, and the edges are held in the straight clamps. The right side of the sacrum (S) is visible. The right ureter passes beneath the peritoneal clamp on the right side. E. This picture is taken from the direct overhead position. The uterus (U) is anterior. The sigmoid colon (SC) is in the foreground, out of focus. The presacral space is being opened to the right of the midline but medial to the right ureter. The peritoneal edges are labeled P. The sacrum (S) is being exposed. F. View taken from the right caudal angle. The scissors point to the sacral promontory. The sigmoid colon (SC) is tented up by the surgeon. The sigmoid colon can be easily followed down over the presacrum as it first swings to the right and then joins to the rectum, which is 75% retroperitoneal. Note that the uterus is held in the Kocher clamp. G. The curved clamp points to the middle sacral vessels. Above, two strands of the hypogastric plexus descend into the presacral space.

FIGURE 36–20 The spread tip of the clamp exposes the hypogastric plexus over the aorta.

FIGURE 36–21 The main mass of the hypogastric plexus is displayed above the underlying clamp.

FIGURE 36–22 Panoramic view of the bifurcation and the hypogastric nerve. To the immediate left is the inferior mesenteric artery arising from the aorta and branching to supply the colon. Farther to the left (clamp) is the left ureter crossing over the left common iliac artery. To the right is the right common iliac artery. The right ureter crosses over the lower portion of the iliac just cranial to (above) the point where the ureter crosses.

FIGURE 36–23 The left ovarian vessels are shown at the point where the vein enters the left renal vein and the artery enters the aorta.

FIGURE 36–24 Panoramic view of the right ovarian vein entering the vena cava (hook) and the artery entering the aorta.

FIGURE 36–25 A. The scissors point to the iliac artery bifurcation. Below are the numerous and frequently anomalous deep pelvic veins. Above is the psoas major muscle. B. Magnified view of Figure 36–25A. The external iliac artery is above and the internal iliac just forward of the scissors.

FIGURE 36–26 The ureter is shown elevated by the scissors.

FIGURE 36–27 A. (Magnified) The scissors point to the posterior division of the hypogastric (internal iliac) artery. B. (Magnified) The scissors point to the internal iliac vein. The anterior division of the hypogastric artery is above the scissors.

FIGURE 36–28 (Magnified) The scissors dissect one of the large sacral roots that contribute to the sciatic nerve.

FIGURE 36–29 Magnified view of the sciatic nerve, which is surrounded by a large mass of pelvic veins.