Anatomy of the Lower Abdominal Wall

The pelvic surgeon is mainly involved with the abdomen below or at the level of the umbilicus. The abdominal wall below the level of the umbilicus consists of skin, fat, fascia, and several relatively thin muscles.

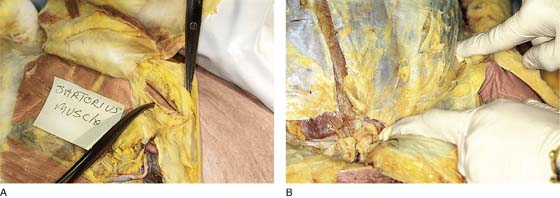

Specific skin and bony landmarks should be noted (e.g., the umbilicus roughly overlies the bifurcation of the aorta) (Fig. 7–1). The anterior superior iliac spine marks the origin of the inguinal ligament and of the sartorius muscle. The upper surfaces of the pubic bone and symphysis mark the terminus of the inguinal ligament and the insertion of the rectus abdominis muscle (Fig. 7–2).

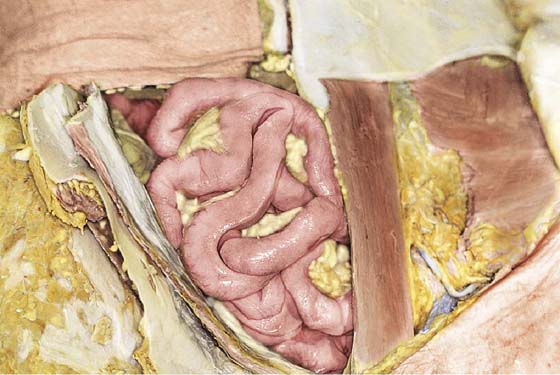

The cadaver is typically in the supine position (see Fig. 7–1). The abdominal wall from superficial to deep consists of skin, subcutaneous fat, fascia, muscle, properitoneal fat, and peritoneum. Once the skin and fat are dissected away, the gray-white glistening fascia comes into view (see Fig. 7–2). This is the superficial investment layer of the underlying muscle (Fig. 7–3). When all layers have been traversed, the peritoneal cavity is entered. The peritoneum of the anterior wall is called the parietal peritoneum, and the peritoneum investing the viscera is known as the visceral peritoneum. The large and small intestines are directly beneath the parietal peritoneum of the anterior abdominal wall (Fig. 7–4).

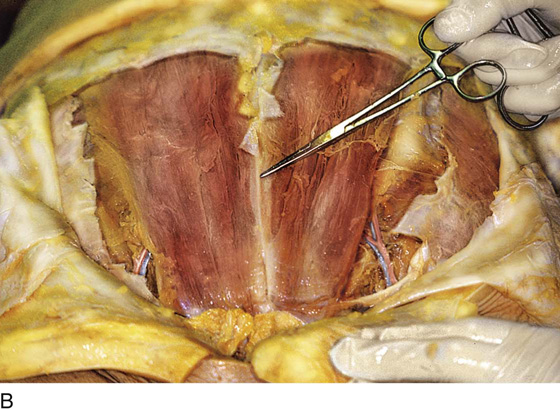

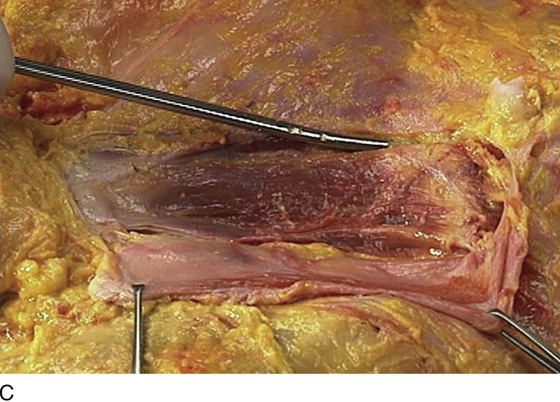

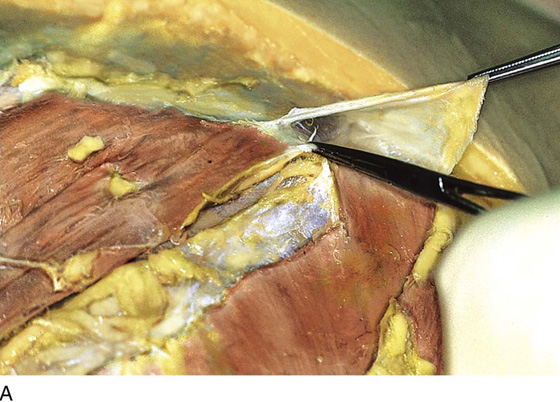

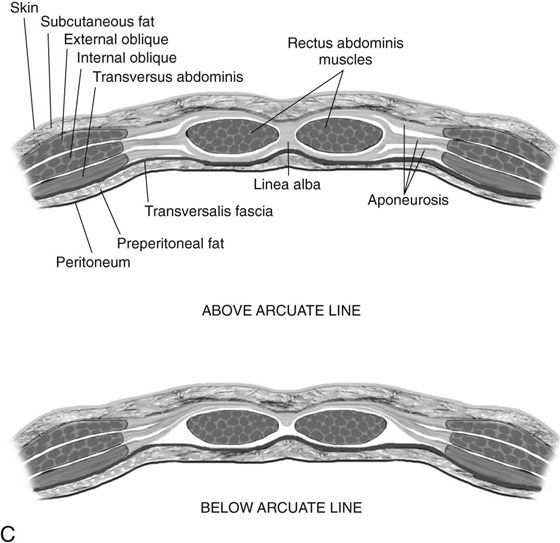

The strength of the otherwise thin layer of muscle and fascia derives from the crisscrossing of various muscle fibers. The external oblique muscles are vectored downward (caudally) and medially. The rectus muscles run straight up and down (vertically) from the xiphoid to the symphysis pubis (Figs. 7–5 and 7–6). It is interesting to note that the tough fascial sheath of the rectus muscles is formed by contributions of other muscles of the anterior abdominal wall (i.e., the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles [Fig. 7–7]).

At the point where the two rectus muscles join in the midline, a white line, aptly called the linea alba, is visible (see Fig. 7–5B).

The fibers of the internal oblique muscle cross those of the external oblique. Similarly, the transversus abdominis muscle crosses both the internal and external oblique muscles as it vectors in an almost horizontal direction. Throughout, the posterior rectus sheath contains transversalis fascia (Fig. 7–8).

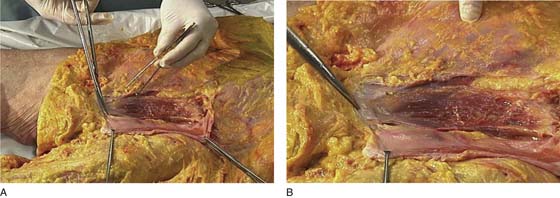

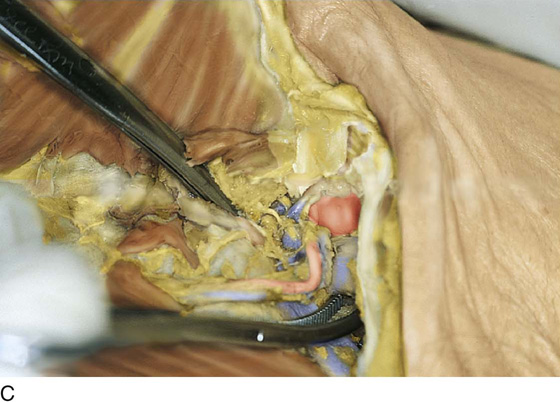

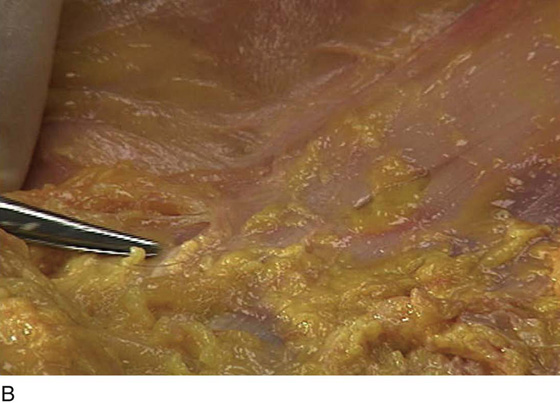

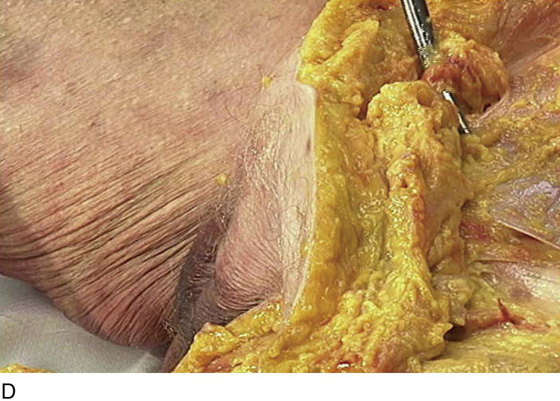

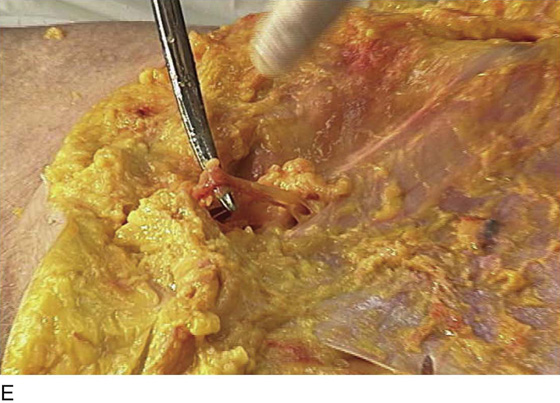

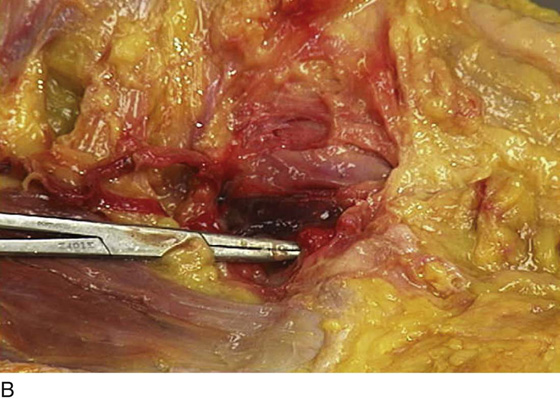

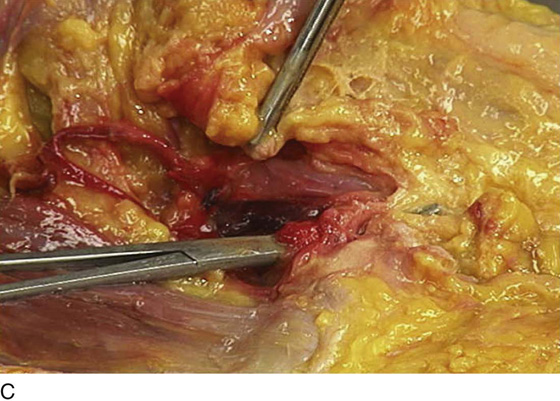

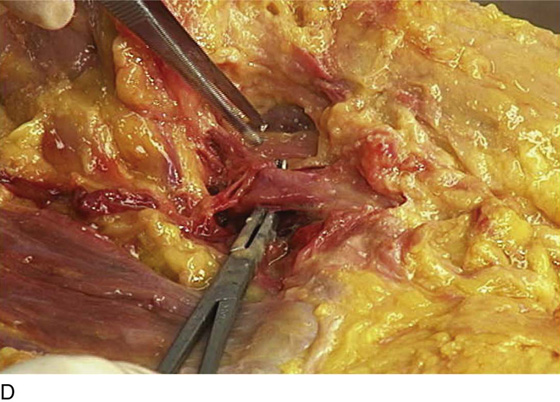

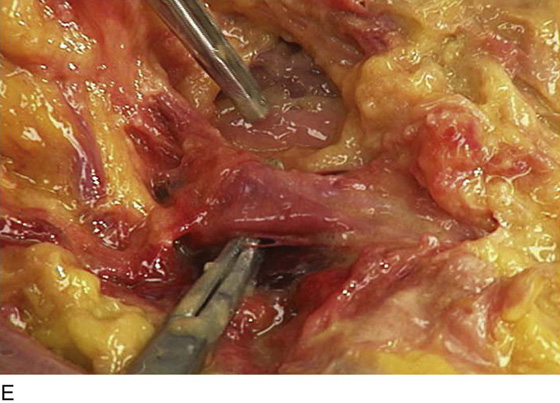

The inguinal ligament and canal are seen in the lowest portion of the abdomen. Actually, the ligament is an anatomic boundary between the abdomen and the thigh (Figs. 7–9A–C and 7–10). As the external iliac vessels cross between the pubic ramus and the inguinal ligament, they become the femoral artery and vein. The inguinal ligament and the sartorius muscle of the thigh originate at the anterior superior iliac spine (Fig. 7–11A). The length of the inguinal ligament may be accurately estimated by placing one finger on the iliac spine and another finger on the pubic tubercle (Fig. 7–11B) and measuring the distance between these fingers. The internal inguinal ring is the point of entry (into the inguinal canal) for intra-abdominal structures, such as the round ligament. They exit the canal onto the abdominal wall via the superficial inguinal ring (Fig. 7–12A–E).

FIGURE 7–1 Important skin surface landmarks include the umbilicus, the anterior superior iliac spines, the pubic symphysis, and the xiphoid process.

FIGURE 7–2 After the lower abdominal flaps have been retracted, the gray-white fascia (aponeurosis) of the external oblique and rectus abdominis muscles is in clear view. The arrows indicate surface landmarks (umbilicus [upper arrow], anterior superior iliac spine [lower arrow], and upper margin of the pubic symphysis).

FIGURE 7–3 Skin and fat have been retracted except for the area of the mons. The fascia of the external oblique and rectus abdominis is intact.

FIGURE 7–4 The peritoneal cavity has been entered. The small and large intestines occupy the entire space within the lower abdomen. They constitute the most superficial viscus encountered in the abdominal cavity.

FIGURE 7–5 A. The anterior portion of the rectus abdominis muscle sheath has been incised and retracted, exposing the vertical fibers of the muscle. B. It is clear from this photograph how the name of the linea alba originated. C. The scissors point to the diastasis recti.

FIGURE 7–6 A. The left rectus abdominis muscle has been exposed. B. Enlarged view of the left rectus abdominis muscle. The scissors point to the pubic tubercle.

FIGURE 7–7 A. The external oblique muscle has been retracted. Part of the rectus sheath has been removed (left-center), exposing the rectus muscles. The contribution of the internal oblique fascia to the rectus sheath is demonstrated (clamps). B. The tip of the clamp rests on the fascia of the transversus abdominis muscle (transversalis fascia), which in turn constitutes the posterior rectus sheath. C. Cross-sectional drawings of the anterior abdominal wall show the formation of the rectus sheath above and below the arcuate line (one-third the distance from the umbilicus to the symphysis pubis). Note that below the line, the anterior sheath receives components from the external and internal oblique muscles and the transversus. The posterior sheath is thin and consists only of transversalis fascia.

FIGURE 7–8 The transversus muscle fibers are directed straight (horizontally) across the abdomen rather than obliquely.

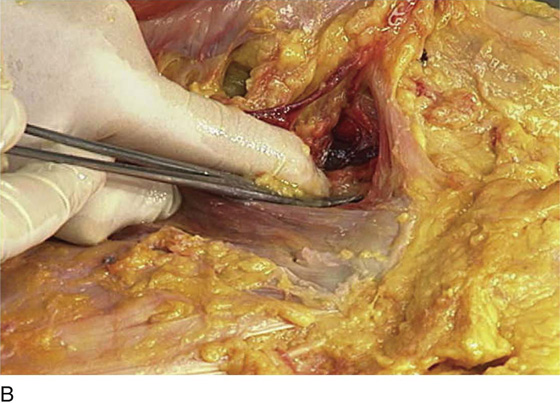

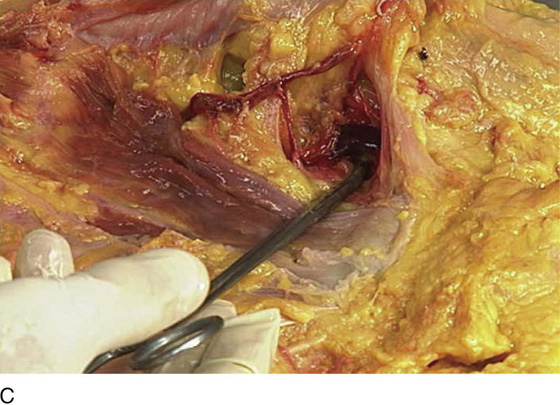

FIGURE 7–9 A. The scissors tip points to the left anterior superior iliac spine. The dissector’s hand is placed in the crural area beneath the inguinal ligament on the right. B. The scissors tip is beneath the left inferior epigastric vessels. These vessels originate from the external iliac vessels at a point immediately cranial to their passage beneath the inguinal ligament. C. The lower (opened) clamp lies on the transversalis fascia and under the left external iliac vein as it crosses beneath the inguinal ligament.

FIGURE 7–10 The clamp points to the transversus muscle.

FIGURE 7–11 A. The curved clamp points to the sartorius muscle. This muscle has a common origin with the inguinal ligament from the anterior superior iliac spine and forms the lateral margin of the femoral triangle (in the thigh). B. The course of the inguinal ligament is marked by the surgeon’s fingers. Note the intact but dissected rectus sheath.

FIGURE 7–12 A. The scissors tip is placed into the right superficial inguinal ring. B. Magnified view of the superficial inguinal ring. Note the inguinal ligament, which is a deeper pink color. C. The round ligament (above scissors) emerges from the superficial inguinal ring. D. The round ligament descends into the fat of the mons, then into the fat of the labium majus. E. The ilioinguinal nerve also exits via the superficial inguinal ring. Note the white-pink inguinal ligament in the background.

Vessels

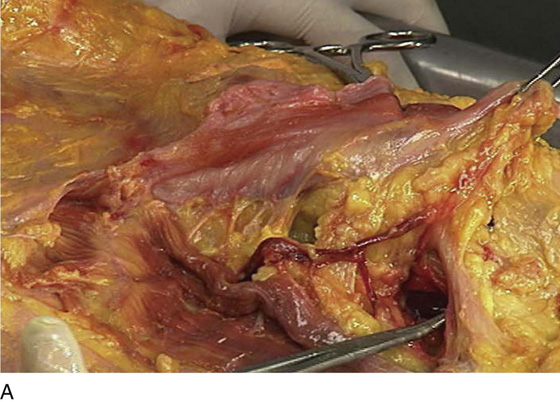

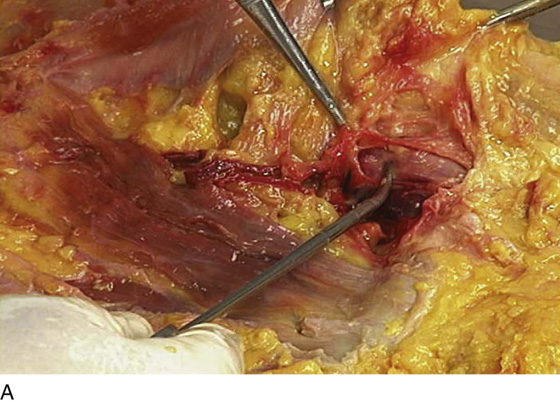

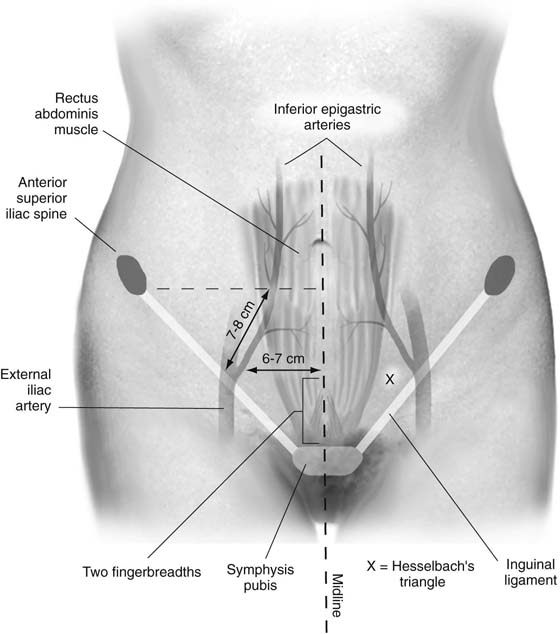

The inferior epigastric vessels take their origin from the external iliac vessels at a point cranial to the inguinal ligament. The inferior epigastric vessels pierce the transversalis fascia and run across the transversus muscle to enter a space between the rectus muscle and the posterior sheath (Fig. 7–13). The external oblique is reflected laterally to demonstrate the inferior epigastric vessels, ascending cranially at the lateral margin of the left rectus abdominis muscle. The left inferior epigastric vessels are shown crossing the abdominal wall toward the edge of the left rectus abdominis muscle (Fig. 7–14). Hesselbach’s triangle, which is formed by the inguinal ligament, the inferior epigastric, and the lower lateral margin on the rectus muscle, is shown in Figure 7–15. The inferior epigastric artery can be traced to the external iliac artery and crosses over the external iliac vein (Fig. 7–16A, B). The external iliac vessels cross into the thigh under the inguinal ligament. The femoral canal and Cloquet’s lymph node lie just medial to the external iliac vein (Fig. 7–17A–E). The superior pubic ramus and the lateral portion of the iliopectineal line and ligament (Cooper’s ligament) are in close proximity to the iliac and inferior epigastric arteries. Figure 7–18 illustrates the typical course of the inferior epigastric vessels relative to lower abdominal landmarks. Figure 7–19 details the cadaver dissection data that were used to compile the quantitative aspects of Figure 7–18. Two fingers were placed above the upper margin of the symphysis pubis. The ruler indicates that the distance from midline to the inferior epigastric vessels is 6 to 7 cm.

FIGURE 7–13 The inferior epigastric vessels run from lateral to medial and ascend between the lateral margin of the rectus muscle and the posterior sheath (transversus fascia).

FIGURE 7–14 The left rectus abdominis muscle is elevated. The inferior epigastric vessels have been dissected at the lateral margin of the muscle. The Allis clamp holds the opened anterior rectus sheath.

FIGURE 7–15 A. The inferior epigastric vessels have been dissected laterally and inferiorly in the direction of the inguinal ligament. The clamp points to the external iliac vein. B. The clamp has been moved medially and rests on the pubic bone and points directly to the distal inguinal ligament. C. This magnified view shows the external iliac vein at a point immediately cranial to the inguinal ligament.

FIGURE 7–16 A. The clamp points to the origin of the inferior epigastric artery from the external iliac artery. This point is located just above the inguinal ligament (arrow). B. Magnified view of the external iliac vessels crossing into the thigh sandwiched between the pubic bone and the inguinal ligament (Kocher clamp holds the inguinal ligament). The tonsil clamp rests on the external iliac artery.

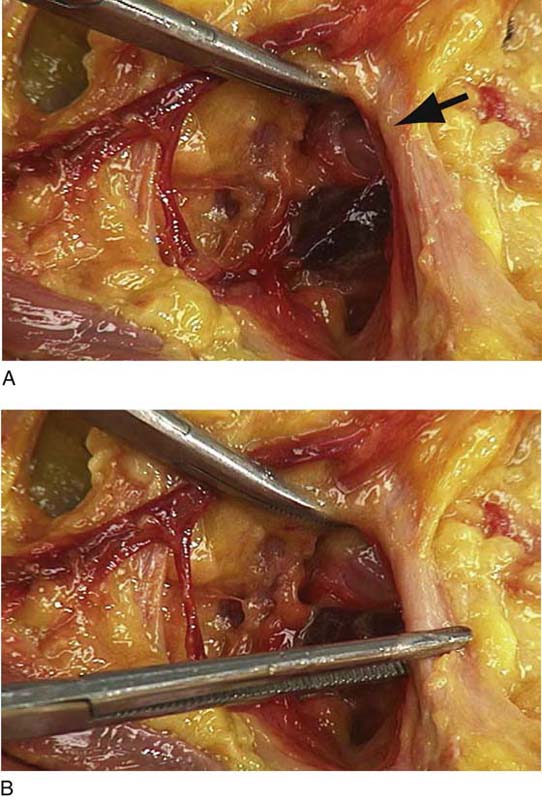

FIGURE 7–17 A. The inguinal ligament has been cut. The external iliac (femoral) artery is exposed by the tonsil clamp. B. The Kelly clamp is just beneath Cloquet’s lymph node (the lowest node in the external iliac chain). Note the location is immediately medial to the iliac (femoral) vein. C. The clamp has been advanced through the femoral canal. Note the tip of the Kelly clamp within the fat of the thigh. The Kocher clamp holds the superior cut margin of the inguinal ligament. Immediately lateral to the femoral canal is the external iliac (femoral) vein, followed still further laterally by the external iliac (femoral) artery. D. The clamp has been positioned under the external iliac artery. The forceps rest on the psoas major muscle. E. Magnified view of part D showing the light pink psoas major muscle (forceps).

FIGURE 7–18 A point two fingerbreadths (4 cm) above the upper margin of the pubic symphysis in the midline serves as a useful landmark for demarcating the origin of the inferior epigastric artery. By measuring 6 to 7 cm from this point in a straight line laterally, one reaches the point where the inferior epigastric penetrates the fascia of the transversus abdominis muscle. The vessel proceeds upward obliquely for 7 cm to enter the posterior rectus sheath.

FIGURE 7–19 The ruler measures from the linea alba laterally to the inferior epigastric vessels, a distance of exactly 6.4 cm.