Anatomy of the Groin and Femoral Triangle

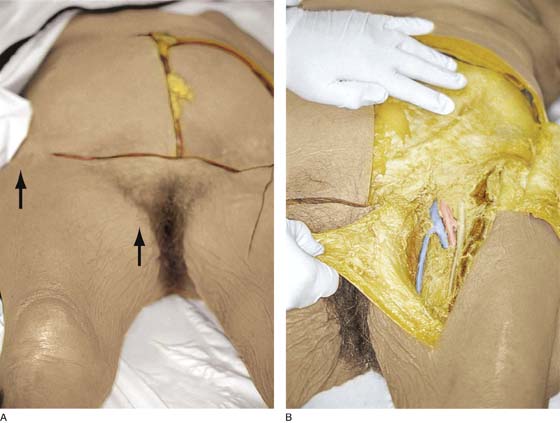

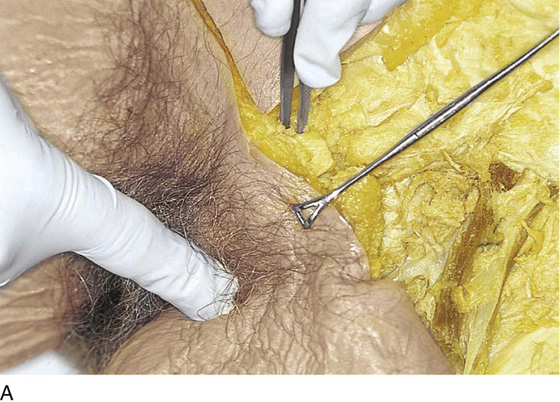

Knowledge of inguinal anatomy is essential before vulvectomy is performed. The lymphatics of the vulva drain to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes and to the femoral and external iliac nodes. To expose the area, an incision is made on the thigh just below and parallel to the inguinal ligament (Fig. 70–1A). A second incision is made to intersect with the first at the anterior superior iliac spine and is continued caudally toward the apex of the femoral triangle. The flap created is dissected medially (Fig. 70–1B).

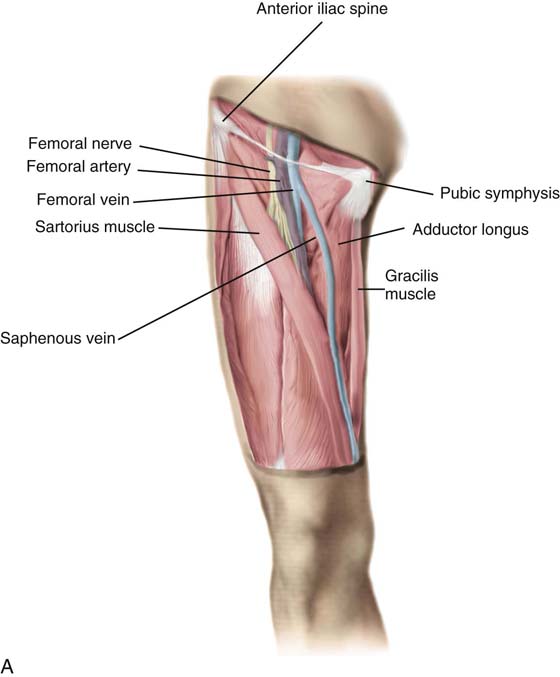

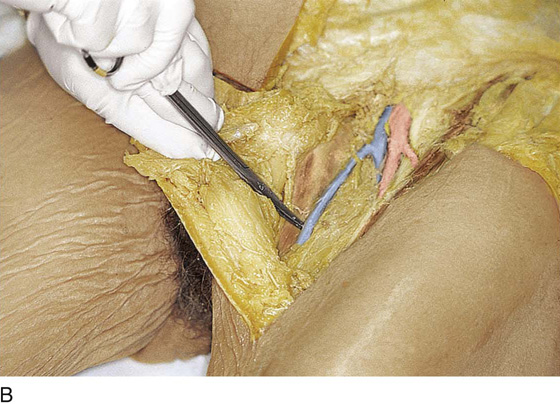

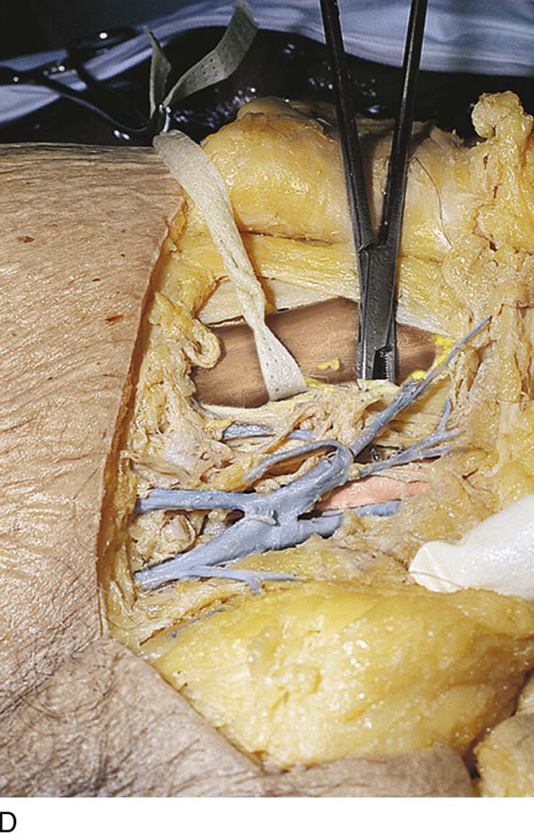

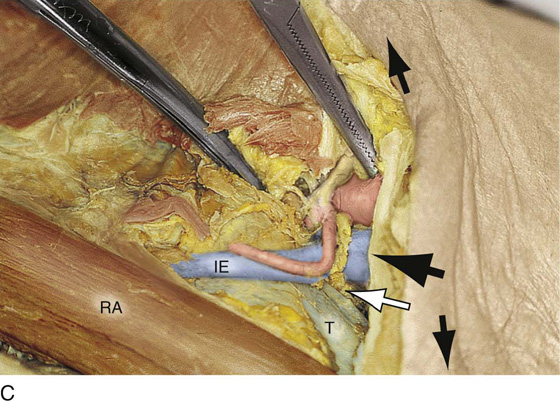

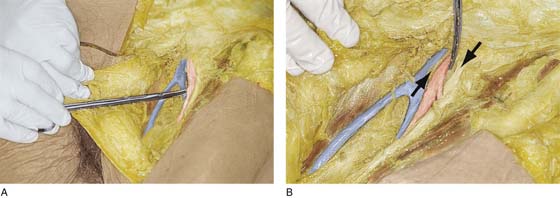

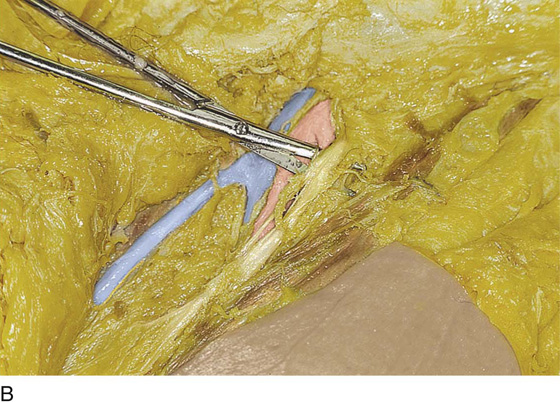

The triangular area is bordered laterally by the sartorius muscle and medially by the pectineus and adductor longus muscles (Fig. 70–2A). Traveling from below upward within the medial aspect of the fat above the aforementioned medial muscles is a large vessel, the saphenous vein (see Fig. 70–2A). The vein pierces the cribriform fascia overlying the fossa ovalis and the femoral vessels and joins the femoral vein below the fascia (Fig. 70–2B). The femoral vein lies in its own tough fascial compartment. Several small veins and arteries join to or branch from the femoral vein and artery: (1) the superficial circumflex iliac, (2) the superficial epigastric, and (3) the superficial external pudendal (Fig. 70–2D). Directly medial and slightly posterior is the femoral canal, which is a potential space juxtaposed medially to the pubic bone (Fig. 70–3A). This canal may contain the lowest node of the external iliac chain, Cloquet’s node (Fig. 70–3B, C). Just lateral to the femoral vein, again within its own fascial compartment, lies the femoral artery, which accompanies the vein in a caudal and deep descending course (Fig. 70–4A, B). Finally, most lateral and again with a tough fascial compartment is the femoral nerve, which descends into the thigh as a series of branching, diverging fibers (Fig. 70–5A, B). The femoral nerve is vulnerable to injury during positioning of the inferior extremities for perineal operations (Fig. 70–5C). The inguinal ligament crosses the nerve perpendicularly, where the nerve probably is most exposed. The tight inguinal ligament therefore can put sufficient pressure on the underlying nerve to result in palsy. The nerve also may be injured by a hyperextended lithotomy position (high lithotomy) coupled with abduction at the thigh (Fig. 70–5D). This type of stretch injury occurs in the vicinity of the lumbar plexus, where the obturator nerve joins the lumbar plexus between the femoral nerve and the lumbosacral trunk (Fig. 70–5E). The obturator nerve and the relatively superficial genital femoral nerve are more susceptible to retractor injuries than is the femoral nerve, which is buried in the substance of the psoas major muscle (see Fig. 70–5D).

Farther lateral is the sartorius muscle, which in concert with the inguinal ligament takes its origin from the anterior superior iliac spine (Fig. 70–6A, B). It is useful to transplant this muscle over the exposed femoral vessels after a radical vulvectomy and inguinal lymphadenectomy (Fig. 70–6C).

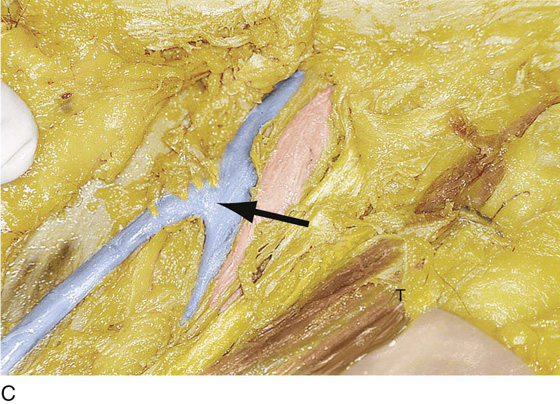

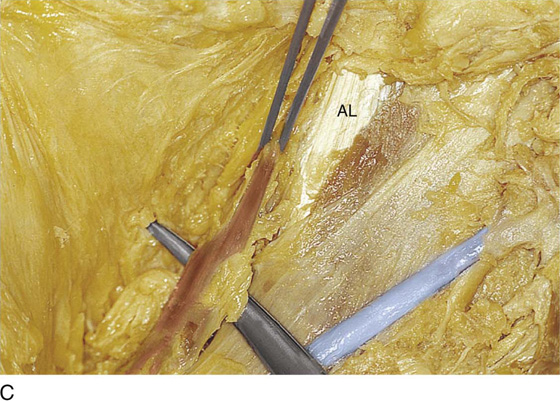

The gracilis muscle is located at the medial side of the femoral triangle (i.e., medial and deep to the saphenous vein). This structure is useful as a myocutaneous flap for transplant to the vulva or vagina (Fig. 70–7A through C).

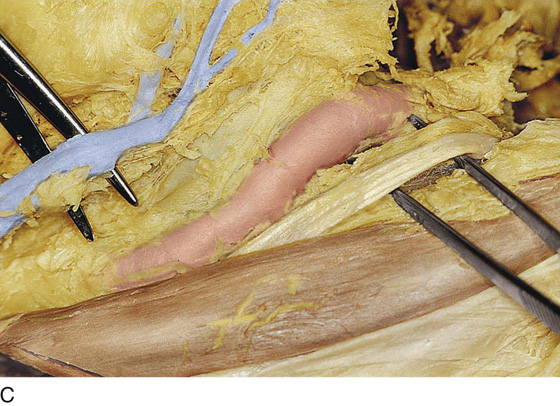

FIGURE 70–1 A. The inguinal area and the femoral triangle are located caudal to the inguinal ligament. The initial incision to expose the area is made in the thigh parallel to and below the inguinal ligament (between the two arrows). B. The second incision intersects with the first (see part A) at the anterior superior iliac spine and extends inferiorly toward the apex of the femoral triangle. The excision extends into the subcutaneous tissue. The flap is dissected medially.

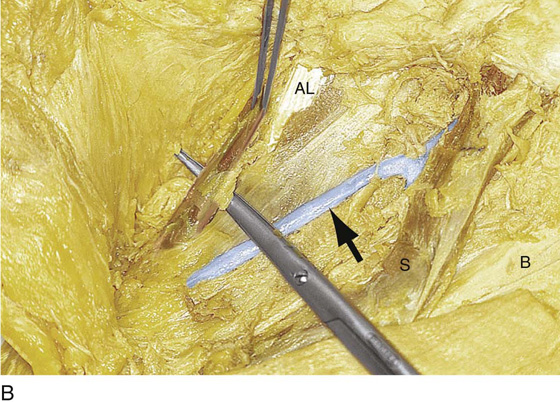

FIGURE 70–2 A. Overall schema of the femoral triangle. Medially is the gracilis muscle. Next to the gracilis is the adductor longus. The sartorius muscle is the straplike muscle extending from lateral to medial and forming the lateral side of the triangle. Behind the sartorius is the rectus femoris muscle. B. The saphenous vein is exposed (scissors are under the vein) as it sweeps through the fat, extending from a medial location in the thigh and vectoring toward the midpoint below the inguinal ligament. C. Close-up view of the saphenous vein penetrating the cribriform fascia and draining into the femoral vein (arrow). The sartorius muscle (S) is seen at the lateral margin of the femoral triangle. D. Several small veins can be seen to join the junction of the femoral and saphenous veins. These small tributaries include the superficial epigastric, superficial external pudendal, and superficial circumflex iliac veins. The umbilical tape has been placed around the sartorius muscle. The surgeon’s gloved finger is on the pubic tubercle (i.e., at the medial insertion of the inguinal ligament).

FIGURE 70–3 A. The scissors are dissecting the space medial to the femoral vein. This is the femoral canal. B. The scissors are lateral to the pubic bone and the lacunar ligament, beneath the terminal portion of the inguinal ligament, and medial to the femoral vein. The scissors are within the femoral canal. This canal is a potential space for the formation of a femoral hernia. C. Dissection above the inguinal ligament. The location of the inguinal ligament is shown by the small arrows. The medial border of the left rectus abdominis (RA) muscle is seen at the lower left-hand portion of the picture. The Kocher clamp points to the external iliac artery just cranial to the point where it crosses beneath the inguinal ligament. The external iliac vein is located medial to the artery (large dark arrow). The inferior epigastric (IE) crosses the femoral vein and travels cranially and medially to reach the lateral border of the rectus muscle. The bluish tissue on which these structures lie is the transversalis fascia (T). The open arrow points to the location of the lowest most external iliac node, Cloquet’s node, which lies in the upper portion (cranial) of the femoral canal.

FIGURE 70–4 A. The scissors point to and are directly beneath the femoral artery. B. The probe points to the femoral artery. This vessel lies in its own fascial compartment and is separated from the femoral vein by tough connective tissue (fascia) (arrows).

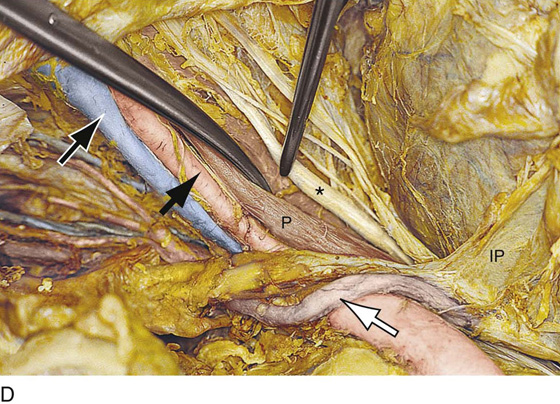

FIGURE 70–5 A. The femoral nerve is situated lateral to the femoral artery. The tip of the scissors lies beneath a branch of the main trunk of the nerve. B. The scissors are spread under the femoral nerve as it emerges from beneath the inguinal ligament. The sartorius muscle is lateral to the nerve. Pressure on the nerve by the inguinal ligament when the inferior extremities are severely flexed can result in femoral nerve palsy. C. Close-up view of the upper femoral triangle. The scissors are spread beneath the saphenous vein. The forceps are spread under the main trunk of the femoral nerve. The forceps arms lie on the sartorius muscle. D. This abdominal dissection demonstrates the upward course of the femoral nerve. The anterior portion of the psoas major muscle (P) has been cut away. The curved scissors sharply depress the medial aspect of the psoas major muscle (P). The tip of the forceps points to the femoral nerve (*), which was embedded within the substance of the psoas muscle. The infundibulopelvic ligament (IP) and the ureter (open arrow) cross the common iliac artery. The external iliac artery (small arrow) and the external iliac vein (outlined small arrow) below the artery are located medial to the retracted muscle. Below the external iliac vein is the dissected obturator fossa. E. Deep within the pelvis, above the sacrum, the femoral and obturator nerves join the lumbosacral trunk. The scissors are beneath the nerves.

FIGURE 70–6 A. The scissors lie on the sartorius muscle. The surgeon’s finger points to its origin on the anterior superior iliac spine. B. The upper portion of the sartorius muscle can be seen (arrow). Note its relationship to the muscles of the anterior abdominal wall. C. Close-up view of the sartorius muscle and the anterior superior iliac spine. The inguinal ligament has been excised.

FIGURE 70–7 A. The clamp is on the cut edge of the upper margin of the mons. The finger of the surgeon points to the medial thigh and the location of the gracilis muscle. B. The medial thigh dissection exposes the fine, delicate gracilis muscle. Note that the blades of the scissors cross the saphenous vein. AL, adductor longus muscle; S, transplanted sartorius muscle (i.e., separated from the anterior superior iliac spine and sutured to the inguinal ligament); B, bed of the original site of the sartorius muscle; arrow, the saphenous vein. C. Magnified view of the gracilis muscle. The muscle arises from the lower portion of the symphysis pubis and pubic bone and inserts onto the medial surface of the tibia. The adductor longus muscle (AL) lies next to the gracilis muscle.