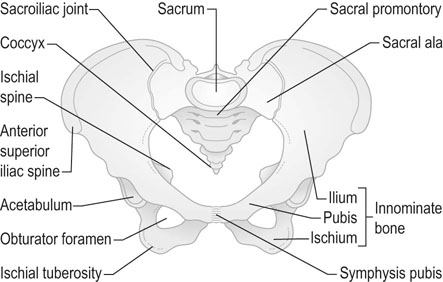

Anatomy of the female pelvis

The structure and function of the genital organs vary considerably with the age of the individual and her hormonal status, as will be apparent in chapter 16, which covers the changes that take place in puberty and the menopause. This chapter aims to outline the major structures comprising the female pelvis, predominantly in the sexually mature female.

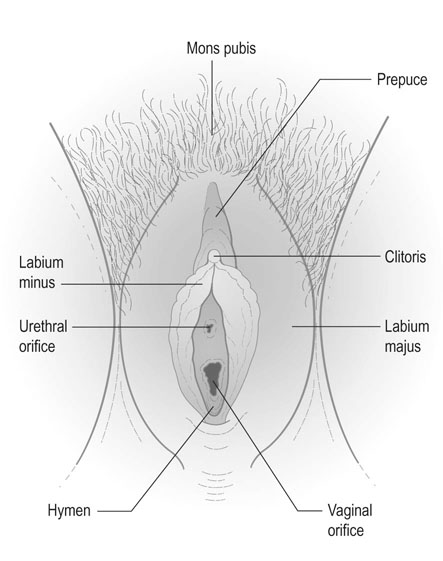

The external genitalia

The term vulva is generally used to describe the female external genitalia, and includes the mons pubis, the labia majora, the labia minora, the clitoris, the external urinary meatus, the vestibule of the vagina, the vaginal orifice and the hymen (Fig. 1.2).

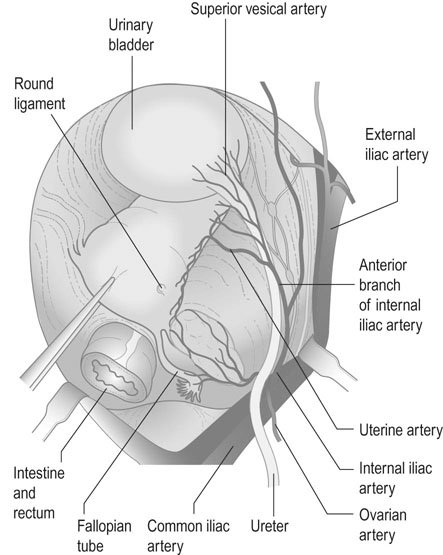

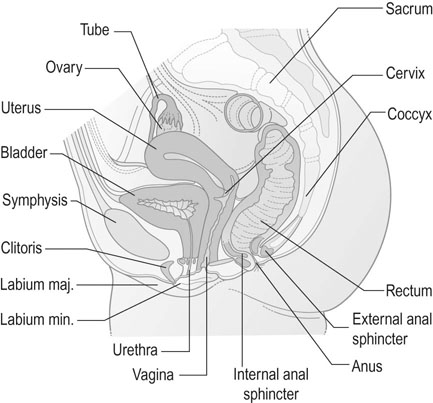

The internal genital organs

The internal genitalia include the vagina, the uterus, the Fallopian tubes and the ovaries. Situated in the pelvic cavity, these structures lie in close proximity to the urethra and urinary bladder anteriorly and the rectum, anal canal and pelvic colon posteriorly (Fig. 1.3).

Supports and ligaments of the uterus

The cardinal ligaments (transverse cervical ligaments) form the strongest supports for the uterus and vaginal vault and are dense fascial thickenings that extend from the cervix to the fascia over the obturator fossa on each pelvic side wall. Medially, they merge with the mass of fibrous tissue and smooth muscle that encloses the cervix and the vaginal vault and is known as the parametrium. The uterosacral ligaments merge with the parametrium. Close to the cervix, the parametrium contains the uterine arteries, nerve plexuses and the ureter passing through the ureteric canal to reach the urinary bladder. Lower down, the muscular activity of the pelvic floor muscles and the integrity of the perineal body play a vital role in preventing the development of uterine prolapse (see Chapter 21).

The Fallopian tubes

The tube is divided into four sections:

• The interstitial portion lies in the uterine wall.

• The isthmus is a constricted portion of the tube extending from the emergence of the interstitial portion until it widens into the next section. The lumen of the tube is narrow and the longitudinal and circular muscle layers are well differentiated.

• The ampulla is a widened section of the tube and the muscle coat is much thinner. The widened cavity is lined by thickened mucosa.

• The infundibulum of the tube is the outermost part of the ampulla. It terminates at the abdominal ostium, where it is surrounded by a fringe of fimbriae, the longest of which is attached to the ovary.

The tubes are lined by a single layer of ciliated columnar epithelium which serves to assist the movement of the oocyte down the tube. The tubes are richly innervated and have an inherent rhythmicity that varies according to the stage of the menstrual cycle and whether or not the woman is pregnant.

The ovaries

The ovaries are paired almond-shaped organs that have both reproductive and endocrine functions.

Beneath the germinal epithelium is a layer of dense connective tissue that effectively forms the capsule of the ovary; this is known as the tunica albuginea. Beneath this layer lies the cortex of the ovary, formed by stromal tissue and collections of epithelial cells that form the Graafian follicles at different stages of maturation and degeneration. These follicles can also be found in the highly vascular, central portion of the ovary: the medulla. The blood vessels and nerve supply enter the ovary through the medulla.

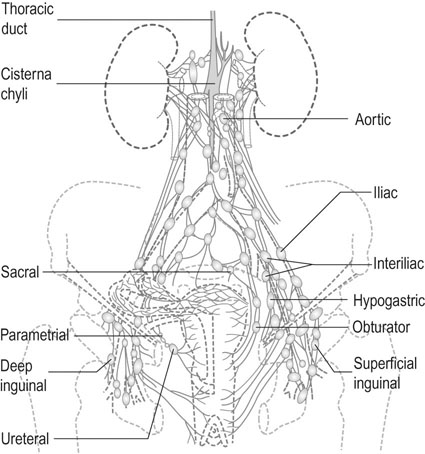

The blood supply to the pelvic organs

Internal iliac arteries

The major part of the blood supply to the pelvic organs is derived from the internal iliac arteries (sometimes known as the hypogastric arteries), which originate from the bifurcation of the common iliac vessels into the external iliac arteries and the internal iliac vessels (Fig. 1.4).

The branches of the two divisions of the internal iliac artery are as follows.

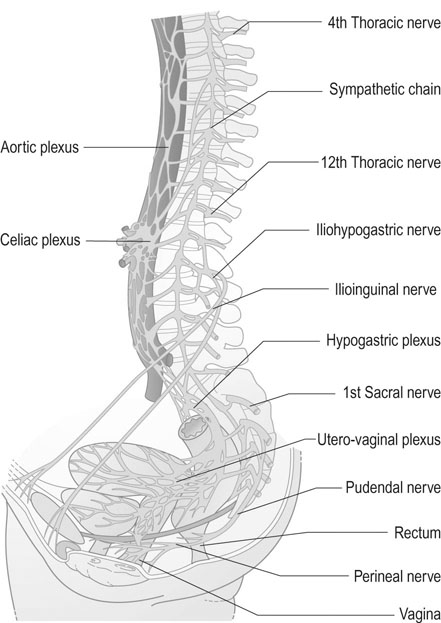

Nerves of the pelvis

The nerve supply to the pelvis and the pelvic organs has both a somatic and an autonomic component. While the somatic innervation is both sensory and motor in function and relates predominantly to the external genitalia and the pelvic floor, the autonomic innervation provides the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve supply to the pelvic organs (Fig. 1.6).

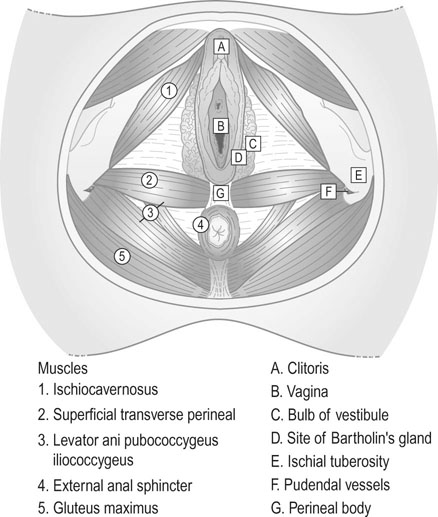

The pelvic floor

The pelvic floor provides a diaphragm across the outlet of the true pelvis that contains the pelvic organs and some of the organs of the abdominal cavity. The pelvic floor is naturally breached by the vagina, the urethra and the rectum. It plays an essential role in parturition and in urinary and faecal continence (Fig. 1.7). The principal supports of the pelvic floor are the constituent parts of the levator ani muscles. These are described in three sections:

• The iliococcygeus muscle arises from the parietal pelvic fascia, extends from the posterior surface of the pubic rami to the ischial spines and is inserted into the anococcygeal ligament and the coccyx.

• The puborectalis muscle arises from the posterior surface of the pubic rami and passes to the centre of the perineal body anterior to the rectum, with some decussation with muscle fibres from the contralateral muscle.

• The pubococcygeus muscle has a similar origin and passes posteriorly to the sides of the rectum and the anococcygeal ligament.

These muscles play an important role in defecation, coughing, vomiting and parturition.