Anatomy of the Cervix

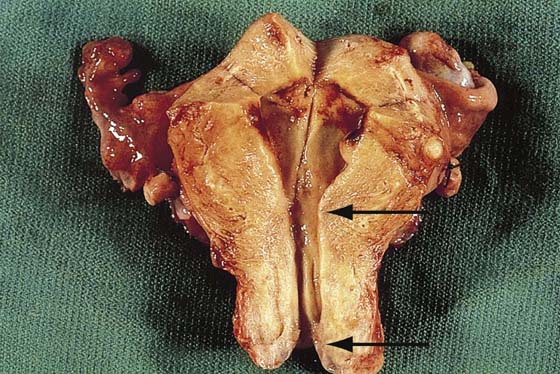

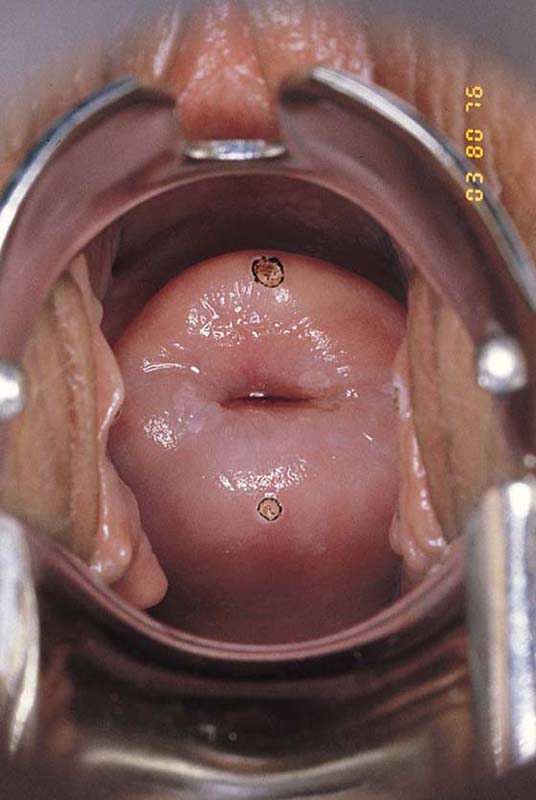

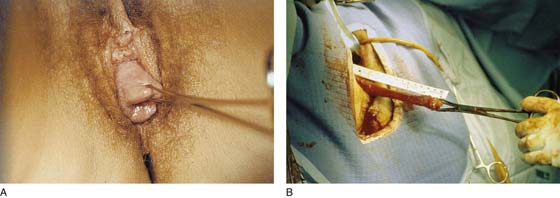

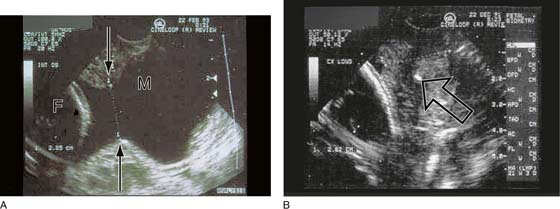

The cervix uteri (cervix) is the lowest portion of the uterus (Fig. 44–1). The cervix consists of roughly equal supravaginal and vaginal portions. The part of the cervix that protrudes into and can be viewed from the vaginal aspect measures 2 cm (average) in length (Fig. 44–2). The supravaginal portion measures 1.5 cm (average) in length. Overall, the entire cervix in the nonpregnant, menstruating woman measures 3.5 cm in length and 2 cm in diameter. During the postmenopausal period or with prolapse, the relative length of the cervix may increase (Fig. 44–3A, B). Similarly, after cerclage, the relative length of the cervix may appear on ultrasound measurement to substantially increase (Fig. 44–4A, B). This apparent increase is undoubtedly due to the addition of a portion of the isthmus into the suture. As the cervix is viewed via an opened speculum, it is cylindrical in appearance with a central opening, the external os. The latter measures 3 to 5 mm in diameter (nulliparous) and up to 1 cm or more in a multiparous woman (Fig. 44–5). The reflection of the upper portion of the vagina (vault) around the protruding cervix forms recesses or fornices (anterior, posterior, right, and left lateral) (Fig. 44–6).

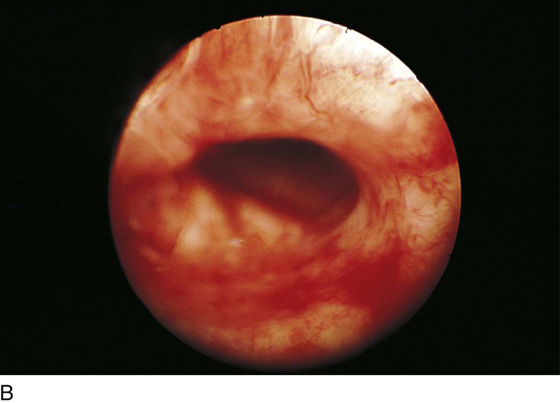

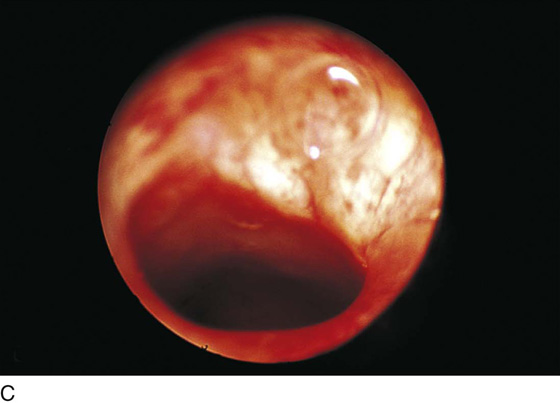

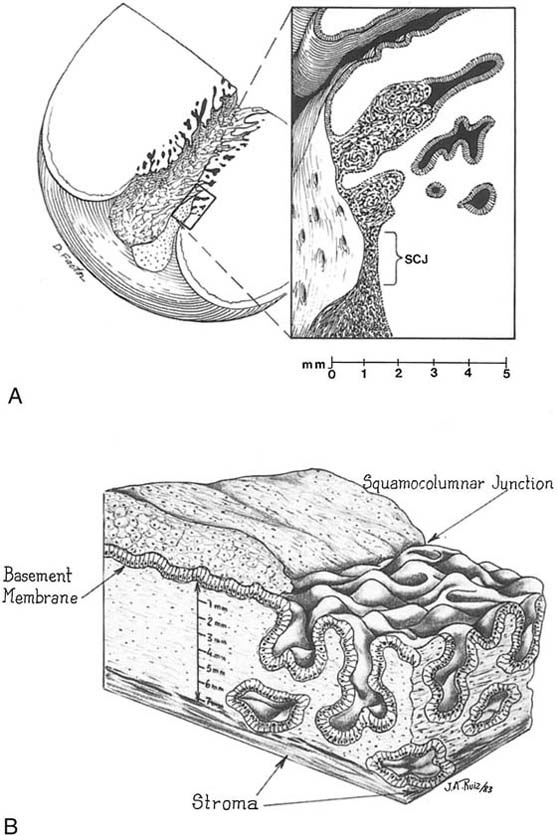

Most of the cervix is covered with multilayered squamous epithelium and has a pink appearance. The endocervical canal is lined by a single layer of glandular mucus-secreting epithelium and has a red coloration (Fig. 44–7). The endocervical canal is narrow (0.5 cm) and extends from the vaginal end (external os) to the point of entry into the lower portion of the uterine cavity (internal os) (Fig. 44–8A through C). The mucous epithelium is thrown into numerous folds and clefts that extend into the underlying stroma (collagen) for varying depths (Fig. 44–9). The purpose of the folds and clefts is to greatly increase the surface area of the endocervical canal without actually increasing its overall length (Fig. 44–10). Unfortunately, a popular misnomer has ingrained itself irreversibly in gynecologic literature and usage: “endocervical glands.” These are not glands but rather an extension of the single-cell–layered endocervical canal. Several studies have shown that the endocervical mucosa projects 3 mm into the underlying stroma but may plunge as deep as 6 mm (Fig. 44–11A, B).

The cervix is endowed with a copious blood supply via the descending branch of the uterine artery and the vaginal artery. This accounts for its ability to miraculously heal and to survive the worst kind of iatrogenic insults.

During pregnancy, the cervix increases in length and even more so in diameter as a result of hyperplasia of both cellular and stromal elements. The greatly increased blood supply lends a dusky or bluish appearance to the tissue, as well as a mushy, soft feeling (Fig. 44–12). As a result of the high levels of estrogens, the endocervical mucosa everts onto the exposed surface of the cervix. In actuality, this is a process of metaplasia in which the reserve cells are programmed to form mucous cells rather than squamous cells.

The nerves supplying the cervix emanate from the vicinity of the sacral end of the uterosacral ligaments. This rather ill-defined combination of tissues constitutes the extra blood and vascular matter at the bottom of the pararectal space, which includes fat, lymphatics, nerves, and connective tissue. It is within this area that the otherwise well-defined uterosacral ligaments terminate.

The inferior hypogastric plexus supplies fibers to this plexus. In addition, fibers are supplied via the sacral roots, and sympathetic input occurs via the lumbar and sacral prevertebral chain (see Unit I, Section A, Chapters 1 and 2).

It is curious that the cervix and the vagina have few pain receptors compared with external skin surfaces or, for that matter, the mucosa of the oral cavity. However, the cervix is well endowed with pressure and temperature receptors. The paracervical plexus and ganglia (Frankenhaüser’s ganglion) may be stimulated via the lateral vaginal fornices to elicit a pleasant sensation with light pressure or a very unpleasant pain elicited by greater pressure.

FIGURE 44–1 The entire uterus is shown in an opened format. The two arrows indicate the entire cervical portion (length), including supravaginal and vaginal portions.

FIGURE 44–2 The portio vaginalis of the cervix measures 2 cm in diameter and 2 to 2.5 cm in length. The cylindrical configuration is obvious. Imprints have been placed with a laser on the anterior and posterior lips of the cervix. The external os is midway between these points.

FIGURE 44–3 A. A greatly elongated cervix is not uncommon in elderly women with prolapse. B. At surgery, the actual length of this long cervix can be appreciated and quantified. Note that the yellowish skin color is due to the povidone-iodine prep.

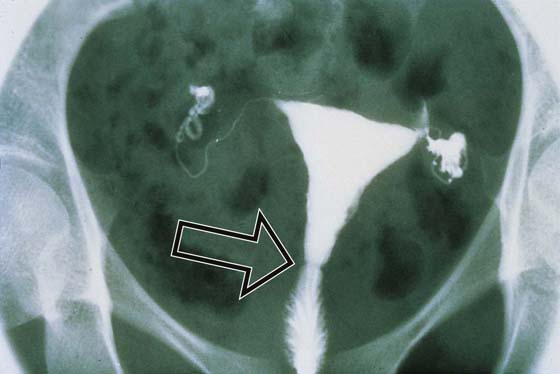

FIGURE 44–4 A. Ultrasonic view of a cervix detailing relative lengths before and after cervical suture placement. The cervix is less than 1 cm in length. The dilated os is at the arrows. Membranes (M) have prolapsed into the vagina. The fetal head is seen at F. B. The arrow points to the knot (white density) of the cervical stitch. Note that the length of the cervix has increased after placement of the suture.

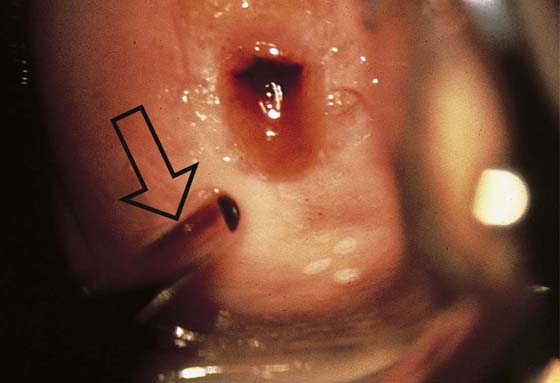

FIGURE 44–5 A contact hysteroscope measuring 6 mm in diameter (arrow) is positioned to enter the endocervical canal. Note that the canal is “more open” at the time of ovulation. The red tissue is mucous epithelium, which lines the endocervical canal.

FIGURE 44–6 The vaginal fornices are created by the protrusion of the cervix through the vaginal vault. This picture clearly illustrates the anterior fornix and the left lateral fornix.

FIGURE 44–7 Close-up view of the cervix showing the squamocolumnar junction. The pink ectocervix sharply contrasts with the red endocervix. The color differences can be explained by the filtration of light between the surface mucosa and the underlying stromal blood vessels. The ectocervix consists of 20 to 40 layers of squamous cells versus the single layer of endocervical mucous epithelium.

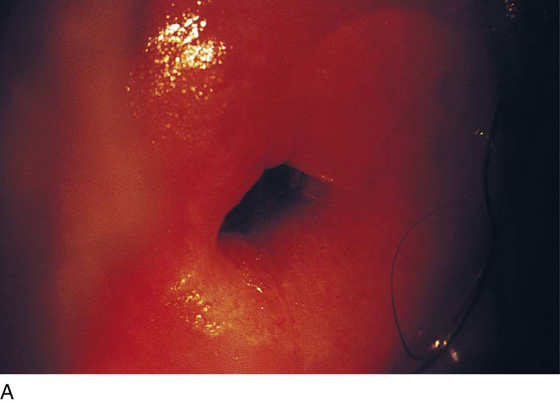

FIGURE 44–8 A. Close-up of the entry point to the cervical canal (external os). B. Hysteroscopic view within the endocervical canal looking upward at the internal os. C. Close-up view at the internal os looking into the lower portion of the uterine corpus (infundibular portion).

FIGURE 44–9 Panoramic carbon dioxide (CO2) hysteroscopic view of the endocervical canal. Note the numerous folds and clefts.

FIGURE 44–10 Hysterosalpingographic detail of the cervix. The internal os is noted at the constriction points (arrow). The endocervical clefts create a feather-like pattern as a result of their extension into the underlying stroma.

FIGURE 44–11 A. Schematic representation of the distribution and geography of the endocervical clefts. The inset shows a detail of the endocervical mucosal surface and the underlying stroma. Note the extent (millimeter rule) of the depth to which the endocervical clefts penetrate the collagenous stroma. B. This three-dimensional rendering further depicts the meandering endocervical canal. The deepest “gland” penetrates the stroma to a depth of 6 mm.

FIGURE 44–12 The pregnant cervix is enlarged, bluish (cyanotic), soft, and everted. The hypervascularity must be considered and managed during any surgical procedure undertaken during the pregnant condition.