Chapter 19 Anatomy of the abdominal wall and aesthetic classification

• Subcutaneous and myoaponeurotic abdominal deformities must be identified.

• Surgery must be planned accordingly to the patient’s deformity, diagnosed either pre- or intraoperatively.

• Look for congenital rectus diastasis intraoperatively to avoid recurrence of rectus diastasis.

• If there is still myoaponeurotic laxity after the approximation of the rectus edges, plication of the external oblique aponeurosis should be performed.

• Supraumbilical undermining should be performed at the minimum width of the supraumbilical area in order to preserve the perforator arteries of the rectus muscle.

Anatomy of the Anterior Abdominal Wall and its Surgical Implications on Abdominoplasty

Subcutaneous Anatomy of the Anterior Abdominal Wall

The subcutaneous tissue of the anterior abdomen is divided into two layers: the superficial (areolar) and the deep (lamellar) layer. The superficial fascia, also called Scarpa’s fascia, separates these two planes. Adipose tissue is thick and dense in the superficial layer, which is evenly distributed over the whole abdomen. The fat tissue in the deep layer is loose. In the infraumbilical area, these layers are very well defined, whereas in the supraumbilical region this separation is not very clear.1 In the infraumbilical area there is a wide variety of thickness of adipose tissue depending on the patient’s weight. It is important to know this anatomy when there is a difference in subcutaneous thickness between the flap and the area inferiorly to the abdominal incision. In such cases, the removal of the lamellar layer deep to Scarpa’s fascia can be a good option. This removal can be performed up to the umbilicus2 or in all the extension of the abdominal flap.

Blood Supply of the Abdominal Wall

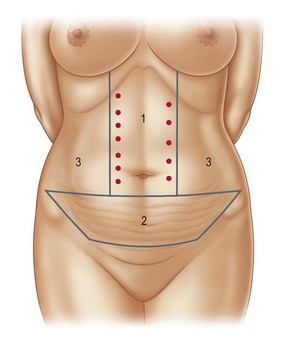

The abdominal skin is supplied by a subdermal arterial plexus originated from a complex network of superficial vessels. Most of these vessels are supplied by the superficial epigastric artery, the superficial circumflex iliac artery, and also from perforators of the superior and inferior epigastric artery. Superficial branches of the intercostal arteries and lumbar branches are also part of this arterial supply.3 When describing the arterial anatomy of the abdominal wall, it is important to define the zones of blood supply which will have an important role in necrosis prevention. There are three areas of blood supply4 that have been described from the perspective of the surgeon. Knowledge of these areas guides the surgeon during abdominal flap undermining (Fig. 19.1). Zone I is the most important area and should be preserved as much as possible during flap undermining. It is located at the supraumbilical region, in which the main arterial flow comes from the perforators of the deep superior epigastric artery. By performing a more localized undermining, surgeons can preserve some of these arteries.

Sensitive Innervation of the Abdominal Wall

The intercostal, subcostal, iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves are responsible for the sensitivity innervation of the anterior abdominal wall.5 The intercostal nerves are branches originating from T7 to T11. The subcostal nerves originate from T12 whereas the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves originate from L1. Branches from T7 to T9 innervate the supraumbilical area, T10 innervates the periumbilical area and the branches originating from T12 and L1 provide innervation to the infraumbilical area.

Lymphatic System

The lymphatic system of the subcutaneous tissue of the supraumbilical area drains to the axillary lymph nodes, whereas the infraumbilical system drains to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes.6 The periumbilical area may also drain to deep abdominal periaortal lymph nodes. Inefficient lymphatic drainage can be one of the causes of seroma.

Myoaponeurotic Anatomy

After describing the rectus sheath anatomy, it is easy to understand why the plication of the anterior rectus sheath is a reliable procedure. As there is a dense attachment between the anterior sheath and the muscle, the plication will effectively bring these muscles together.7–11 However, if these muscles present a lateral origin in the rib cage, recurrence of the plication may occur, as repeated muscle contraction may lead to suture disruption in the upper abdomen.12

The muscles of the flank of the abdomen are the external oblique, internal oblique, and the transverse muscle. The fibers of the oblique muscles are perpendicular to the internal oblique fibers and there is a loose connective tissue between them. This is taken into account if a plication of the external oblique aponeurosis is performed; there is a real decrease of the distance between the origin and insertion of the muscle, thus promoting a more efficient contraction of the muscle and a positive cosmetic effect. It is also important to stress that the arterial supply to the external oblique muscle and its innervation penetrates the muscle laterally to the anterior axillary line.13 Therefore, when the advancement of the external oblique muscle is performed, the undermining on the loose connective tissue above the internal oblique muscle can be performed safely laterally to the anterior axillary line.

The Umbilicus

The attractive umbilicus should have a central depression, a superior skin hood and should also be more vertically shaped. The most accepted position of the umbilicus is at the level above the iliac crests.14 It is not an easy task to achieve all these goals when performing an abdominoplasty. To obtain an attractive umbilicus will depend on the design of the incisions used in the skin and in the umbilicus, on the skin closure tension, and on the abdominal level chosen to place the umbilicus.

Preoperative Preparation

Candidates for abdominoplasty should have a stable weight by the time of the operation to obtain the best possible result. If the patient is overweight and there is some difficulty advancing the flap on the pinch test, weight loss will benefit the patient’s result. Women should be past all their pregnancies before abdominoplasty; however, if a patient gets pregnant after this operation, there is a chance that the musculoaponeurotic deformity will not recur.9 A compressive abdominal garment is used for 1 week before the surgery to adapt the abdominal wall to the myoaponeurotic correction. Smoking and birth control medication should be discontinued for at least 15 days preoperatively.

Diagnosis of the Abdominal Wall Deformities and Surgical Technique

Esthetic Classification of Abdominal Wall Deformities

Deformities of the abdominal wall vary. Each individual will present a specific deformity, depending on inherited characteristics, age and – for women – previous pregnancies. Therefore, a different surgical solution is applicable to each of the abdominal deformities. So that surgeons can easily understand which technique would be more suitable for correcting a specific deformity, two classifications have been described. The first one evaluates excess skin and subcutaneous tissue,15 whereas the other evaluates malpositioning and laxity of the myoaponeurotic layer.16 For each degree of deformity, a specific technique is suggested. Therefore, a combination of the methods described on both classifications can be used, depending on the patient’s deformity.

Classification Based on the Excess Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue

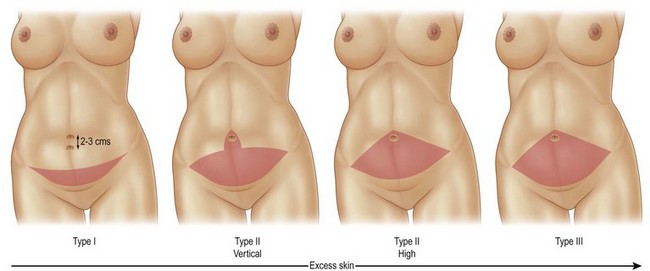

In this classification, deformities are categorized into four different types: 0, I, II and III.

Type 0

Deformity – these patients present an abdominal deformity exclusively due to excessive subcutaneous tissue. There is no excess skin, although some patients may present a little excess skin caused by previous pregnancy or weight loss.

Management – correction of the deformity is achieved by suction lipectomy only (Fig. 19.2).

Type I

Deformity – these patients present little or mild excess skin and a high positioned umbilicus.

Management – an incision usually slightly smaller than those used on classical abdominoplasties is performed tangentially to the suprapubic hairline. The abdominal flap is elevated, exposing the linea alba from the pubis to the xiphoid process. The umbilical pedicle is sectioned and the umbilical skin is maintained with the abdominal flap. The muscular defect is corrected and the excess skin is resected on an area marked with the shape of an Indian canoe. The umbilicus is reattached in the aponeurosis not lower than 2 or 3 cm below its original position (Fig. 19.3).

Type II

Deformity – these are patients with mild excess skin and a well positioned umbilicus. Patients with moderate excess skin with a well or high positioned umbilicus are also included in this group. In such cases, the surgeon is unable to resect the whole area of skin between the umbilicus and the pubic region because there will be not enough skin left with the flap to cover this area. In those patients, two surgical options can be used, depending on patient characteristics.

Management Type II Vertical – indicated in type II patients who present a stable body weight, in those patients with a low abdominal fold and also in patients who present a median supraumbilical scar. In such cases, some of the infraumbilical skin is preserved. There will be a resulting midline scar in the lower abdomen, continuously with the transverse abdominal suprapubic scar. After the undermining, the excess skin is removed under adequate tension. At the end of the operation, the abdomen will present an anchor-shaped scar with a small median vertical scar (Fig. 19.4).

Management Type II High – indicated in type II patients who present a high abdominal fold or for those with weight variations throughout their lives. Patients with a high abdominal fold will have a tendency to have a more discreet scar (Fig. 19.5). This occurs because the incision is placed between the esthetic unities of the abdomen. Also, if patients gain weight after the surgery, a vertical scar may retract, thus dividing the lower abdomen in two areas of subcutaneous projection. In these cases, a high positioned incision is preferable. It is placed from 2 to 3 cm above the pubic hairline, at the patient’s abdominal skin fold. This incision is extended across the whole abdominal width. The undermining exposes the fascia from 1 to 2 cm laterally to the medial edge of the recti muscles and the medial portion of the external oblique muscles. After trimming the excess skin and fat, the remaining abdominal flap can be thinned by removing the fat tissue underneath Scarpa’s fascia whenever the flap is thicker than the suprapubic area. The fascia is kept intact within the flap.

Type III

Deformity – patients included in this group are those with severe excessive skin in the abdomen and with the umbilicus at a high or normal position.

Management – in these cases removal of a fusiform area of skin and subcutaneous tissue from the umbilicus to the pubic hairline is performed (Fig. 19.6). The area undermined in the supraumbilical region is similar to the one described in type II patients. The abdominal flap can also be thinned by removing the fat tissue underneath Scarpa’s fascia whenever necessary.

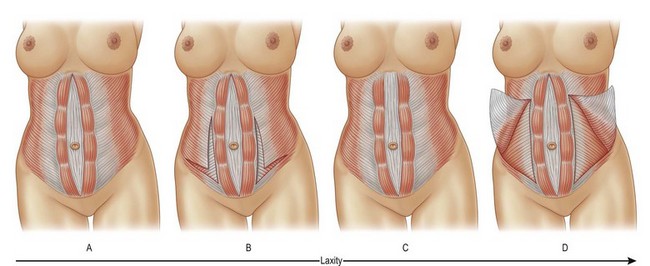

Classification Based on the Myoaponeurotic Deformity

In this classification, deformities are categorized into four different types: A, B, C and D (Fig. 19.7).

Type A

Deformity – these patients present a typical fusiform rectus diastasis secondary to pregnancy. Both recti muscles are inserted on the costal margins close to the midline.

Management – rectus diastasis is corrected by the plication of the anterior rectus sheath. Plication is performed with a two-layer 2-0 nylon suture. The first layer is done using inverted stitches every 0.4 cm and the second layer is a continuous suture. The plication addresses only the correction of the diastasis (Fig.19.6). If the myoaponeurotic layer is still flaccid, the deformity will be classified as type B and another technique is used to correct it.

Type B

Deformity – Type B patients are those who present a persistent bulging of the musculoaponeurotic layer after the correction of diastasis. These patients may present a vertical elongation of the abdominal wall. Patients who need some improvement to the waistline may also benefit from this technique.

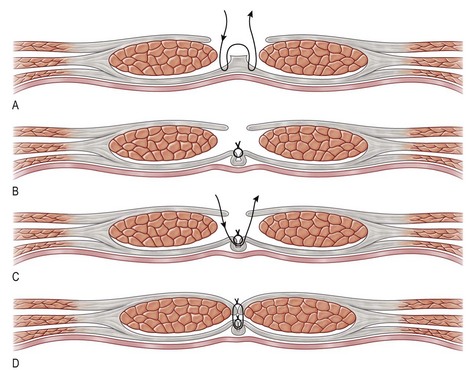

Management – an L-shaped plication of the external oblique aponeurosis should be performed in addition to the plication of the anterior rectus sheath. This plication of the external oblique aponeurosis is done in the same fashion as described for the correction of the rectus diastasis (Fig. 19.8).

Type C

Deformity – Type C patients present a congenital rectus diastasis. In these cases the recti muscles are inserted laterally in the costal margins. These are patients classified by general surgeons as having an epigastric hernia. Although they may not always present hernias, it is a frequently associated defect.

Management – the aponeurotic sheath of the recti muscles should be advanced in these cases. To correct congenital rectus diastasis, an incision is performed along the anterior rectus sheath, close to the linea alba. The rectus muscle is undermined from its posterior sheath. At this point, the linea alba is invaginated using 2-0 nylon inverted sutures and the recti muscles, still attached to the anterior sheath, are advanced towards the midline and anchored to the invaginated linea alba with the same sutures (Fig. 19.9). By using this technique a tension decrease is obtained at the aponeurotic suture.17 A more effective correction is achieved at the upper abdomen (Fig. 19.10).

Type D

Deformity – these patients present musculoaponeurotic laxity of the area of the flank with a poorly defined waistline associated with rectus diastasis secondary to pregnancy.

Management – the external oblique aponeurosis is incised along the semilunaris line, having as the superior limit the costal margins and as the inferior limit the reflected inguinal ligament. The external oblique muscle is undermined laterally towards the anterior axillary line where its neurovascular pedicle penetrates the muscle. An aponeurotic incision is made parallel to the reflected inguinal ligament. This muscle is advanced to the midline and, if possible, sutured to the contralateral one.

Optimizing Outcomes

1. Evaluate excess skin and fat separately from the myoaponeurotic deformity.

2. In order to decrease skin tension between the umbilicus and the skin of the abdominal flap it is sometimes necessary to advance the umbilical pedicle anteriorly by anchoring it to the aponeurosis, so that tension can be decreased.

3. Quilting sutures are important to reduce seroma, hematoma and tension of the abdominal flap, thus reducing flap necrosis.

4. Avoid performing wide rectus plication in cases where the anterior rectus plication was not sufficient to correct the myoaponeurotic deformity. Wide rectus plication can erase the fine contour of the abdominal wall. In such cases, plication of the external oblique aponeurosis is indicated and should be performed.

5. Identify congenital rectus diastasis. In these cases advancement of the rectus muscle should be performed to avoid recurrence of this deformity.

Local Complications and Their Management

Although the number of complications following abdominoplasty has fallen drastically in the last 30 years,18 this operation still has a large range of complications. Scar widening, dyschromic and hypertrophic scars, and dog-ears are common complications that occur after abdominoplasty. Different treatments are used to control these conditions such as chemical peels for hyperchromic scars, intralesional steroid injections for hypertrophic scars, the removal of excess skin in cases of dog-ears and scar excision for the correction of wide scars. Dog-ears can be prevented by sitting the patient up during the operation. The quality of the scar can be improved by good planning and with the use of micropore strips over the scar or silicone. These preventive measures will not avoid all complications but can certainly decrease their incidence.

Sensitivity of the abdominal skin may decrease after abdominoplasty. Usually the most affected areas are the region between the umbilicus and the pubic area and the pubic region itself. The main modalities of sensitivity loss are to pressure and heat.5 Therefore, these patients are more exposed to contact burn accidents on hot surfaces such as hot ovens and barbecue grills. When lipoabdominoplasty is used, the innervation of the abdominal flap is kept intact, thus preserving skin sensibility in these areas.19

Umbilical constriction is not a frequent complication, but it may be troublesome. Most plastic surgeons try to obtain a small umbilicus, which is a sign of youth and esthetically pleasing. However, if there is excessive tension at the edges of the skin to be sutured to the umbilicus, dehiscence can occur and a circular scar will constrict the umbilical area. There is an expected shortening of the umbilical pedicle after the plication of the anterior rectus sheath. The umbilical pedicle fixation to the anterior rectus fascia permits the surgeon to control the pedicle height and consequently the tension at the skin edges during the suture. Therefore, in some cases, the skin pedicle should be advanced superficially, using the aponeurosis as a step to obtain tension decrease of the skin suture between the umbilical skin and the abdominal flap.20

Seroma is the most frequent complication of abdominoplasty. Baroudi and Ferreira in 199821 described the use of quilting sutures to avoid this complication. Nahas et al22 have verified that this technique is efficient in patients with risk factors for developing seroma, for example those who are overweight, those who have presented massive weight loss, and those with supraumbilical scars. Di Martino et al23 have shown that the use of quilting sutures during abdominoplasty was more successful in preventing seroma than when lipoabdominoplasty was performed. Therefore, seroma can be prevented in most cases. However, when seroma occurs, aspiration of this fluid should be done every 3–4 days until there is a decrease in volume to less than 20–40 ml. If seroma is not recognized or if it is not aspirated, its absorption can be delayed and a capsule will be formed around it. A deformity of the abdomen will occur and an extensive undermining is usually necessary to correct this secondary complication.24

Abdominal flap necrosis can be a dramatic complication depending on its extension. The most common causes of necrosis after abdominoplasty are excessive tension and extensive undermining. Preoperative planning based on the type of skin and subcutaneous deformity can help to prevent excessive tension of the abdominal flap.15 The area of undermining can be decreased at the upper abdomen. A narrow undermining tunnel can preserve some of the rectus perforator arteries, thus increasing the arterial flow of the flap. Mayr et al25 demonstrated that there is a decrease in blood flow in the infraumbilical area of the abdominal flap to 17.2% as compared to the normal blood flow after a more extensive flap undermining during abdominoplasty. Therefore liposuction of the abdominal flap should be carefully done. Lipectomy of the flap can be a better choice when it is necessary to decrease flap thickness.2 Quilting sutures can also decrease flap tension. These sutures are progressively placed attaching the skin flap to the aponeurosis, thus decreasing tension on the skin edge.26

Recurrence of myoaponeurotic deformities is another complication that will force the surgeon to perform an extensive surgery to correct it. It usually occurs when the most appropriate technique to correct a specific defect was not used. Patients with type C myoaponeurotic deformities may present recurrence of rectus diastasis in the upper abdomen if plication of the anterior rectus sheath is performed.12 As mentioned before, this complication occurs because the recti muscles present a lateral insertion on the costal margin. However, patients with weak aponeurosis may also present recurrence of the deformities, depending on aponeurotic composition and the predominance of collagen.27

1 Pitman GH. Liposuction and body contouring. In: Aston SJ, Beasley RW, Thorne CHM. Grabb and Smith’s Plastic Surgery. New York: Lippincot-Raven; 1997:669–691.

2 Nahas FX. Refinamentos em abdominoplastia. Rev Bras Cir. 2002;93:58–60.

3 Lowe JB, Lowe JB, Baty JD, et al. Risks associated with “components separation” for closure of complex abdominal wall defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(3):1276–1283.

4 Persichetti P, Simone P, Scuderi N. Anchor line abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(1):289–294.

5 Farah AB, Nahas FX, Ferreira LM, et al. Sensibility of the abdomen after abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(2):577–582.

6 Rubinstein E. Vascularização da parede abdominal. In: Petroianu A, ed. Anatomia Cirúrgica. Guanabara Koogan: Rio de Janeiro; 1999:375–378.

7 Nahas FX, Augusto SM, Ghelfond C. Should diastasis recti be corrected? Aesth Plast Surg. 1997;21(4):285–289.

8 Nahas FX, Augusto SM, Ghelfond C. Nylon versus polydioxanone in the correction of rectus diastasis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(3):700–706.

9 Nahas FX. Pregnancy after abdominoplasty. Aesth Plast Surg. 2002;26(4):284–286.

10 Nahas FX, Ferreira LM, Augusto SM, et al. Long-term follow-up of correction of rectus diastasis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(6):1736–1741.

11 Nahas FX, Ferreira LM, Ely PB, et al. Rectus diastasis corrected with absorbable suture: a long-term evaluation. Aesth Plast Surg. 2011;35(1):43–48.

12 Nahas FX, Ferreira LM, Mendes J de A. An efficient way to correct recurrent rectus diastasis. Aesth Plast Surg. 2004;28(4):189–196.

13 Nahas FX. Advancement of the external oblique muscle flap to improve the waistline: a study in cadavers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(2):550–555.

14 Barbosa MV, Nahas FX, Sabia Neto MA, et al. Strategies in umbilical reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesth Surg. 2009;62(6):e147–e150.

15 Nahas FX. A pragmatic way to treat abdominal deformities based on skin and subcutaneous excess. Aesth Plast Surg. 2001;25(5):365–371.

16 Nahas FX. An aesthetic classification of the abdomen based on the myoaponeurotic layer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(6):1787–1795. discussion 1796–1797

17 Nahas FX, Ishida J, Gemperli R, et al. Abdominal wall closure after selective aponeurotic incision and undermining. Ann Plast Surg. 1998 D;41(6):606–613.

18 Matarasso A, Swift RW, Rankin M. Abdominoplasty and abdominal contour surgery: a national plastic surgery survey. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(6):1797–1808.

19 Bello EML, Mitre LF, Nahas FX, et al. Avaliação da sensibilidade cutânea abdominal pós-lipoabdominoplastia. In: Saldanha O, ed. Lipoabdominoplastia. São Paulo: Di Livros; 2004:85.

20 Nahas FX. How to deal with the umbilical stalk during abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106(5):1220–1221.

21 Baroudi R, Ferreira C. Seroma: how to avoid it and how to treat it. Aesth Surg. 1998;18:439.

22 Nahas FX, Ferreira LM, Ghelfond C. Does quilting suture prevent seroma in abdominoplasty? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(3):1060–1064.

23 Di Martino M, Nahas FX, Barbosa MV, et al. Seroma in lipoabdominoplasty and abdominoplasty: a comparative study using ultrasound. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(5):1742–1751.

24 Zecha PJ, Missotten FEM. Pseudocyst formation after abdominoplasty. Br J Plast Surg. 1999;52:500–502.

25 Mayr M, Holm C, Höfter E, et al. Effects of aesthetic abdominoplasty on abdominal wall perfusion: a quantitative evaluation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(6):1586–1594.

26 Pollok H, Pollok T. Progressive tension sutures: a technique to reduce local complications in abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(7):2583–2586.

27 Nahas FX, Ferreira LM. Concepts on correction of the musculoaponeurotic layer in abdominoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2010 J;37(3):527–538.