CHAPTER 7 Anatomy, Evaluation, and Operative Setup for Posterior Ankle Arthroscopy

Arthroscopy of the posterior ankle was originally described as a diagnostic tool. As surgeons became more proficient with the technique, therapeutic procedures were incorporated.1–5 The posterior portion of the ankle is often poorly visualized from traditional arthroscopic portals, and certain lesions are more easily dealt with by performing a dedicated posterior arthroscopy. Although the prone position and the proximity of the tibial neurovascular bundle have led some away from the technique, recent articles demonstrate that the procedure can be undertaken safely.6

ANATOMY

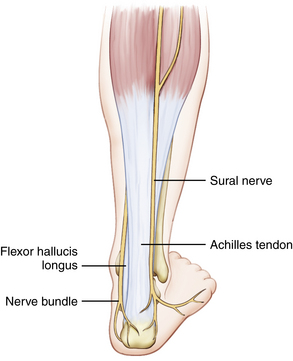

The sural nerve lies lateral to the Achilles tendon at a distance of approximately 1 cm form the lateral edge of the Achilles tendon at the level of the posterolateral portal. It courses obliquely away from the Achilles as it heads toward the lateral portion of the foot. Medially, the flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tendon is encountered first when moving from the margin of the Achilles tendon. Immediately adjacent to that is the tibial nerve. Further medially and anteriorly lie the posterior tibial artery and vein (Fig. 7-1).

FIGURE 7-1 In the drawing of the surface and subcutaneous anatomy, notice the course of the sural nerve.

Retrocalcaneal bursitis is primarily treated nonoperatively, but refractory symptoms can be treated with bursa excision through the arthroscope. The normal bursa is encountered routinely in posterior arthroscopy, because it is often the first potential space developed.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

Retrocalcaneal Bursitis

Retrocalcaneal bursitis is a disease of the tissue adjacent to the insertion of the Achilles tendon on the calcaneus. Some authorities think that it part of a spectrum of disease that includes calcific insertional Achilles tendinitis and that it is not as much an inflammatory phenomenon as it is a fibroproliferative disease of the Achilles insertion, akin to lateral epicondylitits.5 A prominent posterosuperior part of the calcaneus (i.e., Haglund’s deformity) contributes to the symptoms is some patients.2,3,7,8

Watson and colleagues8 described a series of patients with retrocalcaneal bursitis with or without calcific insertional tendinitis. They found that patients without obvious insertional disease fared better than those with a spur. There was a 93% satisfaction rating, with an average time to maximal improvement of 5 months.8

Os Trigonum Syndrome

Nonoperative treatment consists primarily of immobilization and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications. Casting for a period of 4 to 6 weeks with regimented anti-inflammatory medications can relieve symptoms in most patients. For those with recurrent or recalcitrant symptoms, excision of the os trigonum can alleviate pain. Open excision has long been used successfully, but there have been complications related to infection and hematoma.9

Great success with arthroscopic excision has been reported.2–4 Scholten and colleagues thought they were better able to address soft tissue impingement syndromes with posterior arthroscopy. They followed 55 patients for a minimum of 2 years, with none lost to follow-up. They found a significant increase in the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) hindfoot score (75 to 90) and no degenerative changes on repeat radiographs.2

Flexor Hallucis Longus Tenosynovitis

FHL tenosynovitis has long been described in ballet dancers and in athletes with rapid start and stop (toe-off) running, such as soccer players. The repeated stress causes as tenosynovitis, which becomes painful with repetitive use. Rest and omission of painful activities typically alleviate symptoms.

Michelson and coworkers reported a 67% success rate with nonoperative treatment. All of their patients who failed nonoperative treatments had successful outcomes after an open approach to the FHL at the proximal portion of the fibro-osseus tunnel.10

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

Plain Radiographs

Views of the ankle are evaluated for obvious fractures, including an osteochondral fracture of the talus. The tibiotalar joint is assessed for symmetry of the joint space and for degenerative changes, including anterior and posterior osteophytic disease. An os trigonum or fracture of a prominent lateral tubercle of the posterior process of the talus can be seen on the lateral view. Axial and lateral heel views are used to evaluate the calcaneus posterosuperior process, and they typically provide a good view of the posterior facet of the subtalar joint (Fig. 7-2).

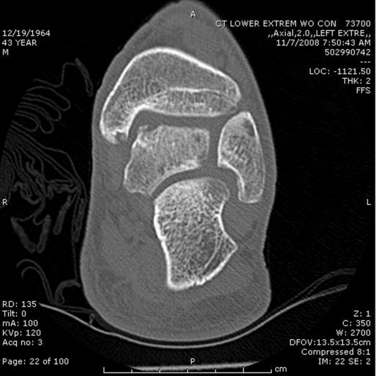

Computed Tomography

CT can show the bony detail of the os trigonum. The os can be an unfused ossification center with a fibrous connection, or it can be a symptomatic, fully fused, large tubercle of the posterior process of the talus. A fracture of the os shows obvious cortical discontinuity on CT (Fig. 7-3).

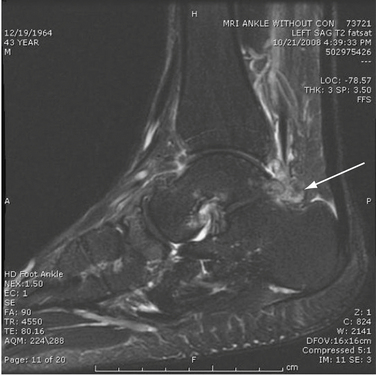

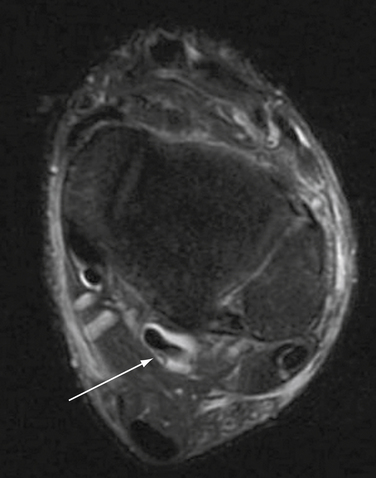

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI provides the greatest amount of information about involved soft tissues. The tendon can be evaluated on standard sequences, but the fluid-sensitive, fat-suppressed images delineate most pathologies better. In these sequences, tendons are typically very dark and homogeneous. Tendons may be torn, split, or surrounded by fluid, which is indicative of tenosynovitis. Attention is focused on the FHL tendon and the anatomy of the posterior neurovascular bundle for operative planning.

In the region of the OLT, the fat-sensitive sequence can show decreased signal intensity in subchondral bone, indicative of edema. Decreased signal intensity can be seen in the cartilage overlying the defect, possibly indicating calcified fibrocartilage in the defect. On the fluid-sensitive sequence, undermining of an unstable cartilage flap can be seen. Fluid-filled cysts are identified. High intensity signal in the bone marrow beneath the OLT indicates inflammation and continued injury (Fig. 7-4).

FIGURE 7-4 A sagittal magnetic resonance imaging shows the same osteochondral lesion of the talus (seen in Figure 7-3. Notice the large area of signal change.

The same signal characteristics hold true for the MRI evaluation of the os trigonum. Edema in the ossicle or in the adjacent posterior talus indicates ongoing injury, supporting its role as the pain generator (Fig. 7-5).

Fluid about the FHL tendon can be seen clearly on fluid-sensitive sequences, and it is an indicator of ongoing inflammation and edema in the tendon. Tendon nodules, hypertrophy, and tears are also identified (Fig. 7-6).

TREATMENT

Surgical Technique

The patient is placed in the prone position. All bony prominences are well padded, and the operative leg is supported on a pad to allow the foot to lie in a neutral position and to provide space to manipulate the foot during the procedure. A thigh tourniquet is placed, and the lower extremity is prepared to the knee (Fig. 7-7).

The Achilles tendon, medial malleolus, and lateral malleolus are palpated and marked. The approximate course of the sural nerve and the posteromedial neurovascular bundle are drawn on the skin. The level of the tibiotalar joint is estimated by palpating the tips of the malleoli and the anterior and posterior joint while moving the foot (Fig. 7-8).

The posterolateral portal is established 5 mm distal to the estimated level of the tibiotalar joint and adjacent to the Achilles tendon. Using an 18-guage needle, 20 mL of arthroscopy fluid is injected into the joint to expand the capsule (see Fig. 7-7). A nick is created in the skin only, and a small hemostat is used to bluntly dissect toward the lateral aspect of the joint. A small joint arthroscopy canula for a 2.7- or 3.0-mm, 30-degree arthroscope with two stopcock valves is placed in this portal. Inflow fluid is placed on one valve, and suction or gravity drainage is attached to the other. By alternating opening the valves, blood can be cleared from the joint and visibility obtained.

The medial portal is established with direct arthroscopic guidance. The entry location in the skin is at the same level as the lateral portal and is adjacent to the Achilles tendon. An 18-guage spinal needle is used to ensure the pathway of the medial portal enters lateral to the FHL. By staying lateral to the FHL the medial neurovascular structures are protected from damage by the arthroscopic instruments (Fig. 7-9).

Instruments are inserted into the joint through the medial portal. A 4-mm, short, plastic cannula may be used to facilitate safe passage of instruments through this portal (Fig. 7-10).

A small amount of the posterior capsule is excised to facilitate visibility of the joint. Because the subtalar joint is close the tibiotalar joint, care must be taken to enter the proper joint. A systematic diagnostic examination of the joint starts at the posteromedial talus (Fig. 7-11).

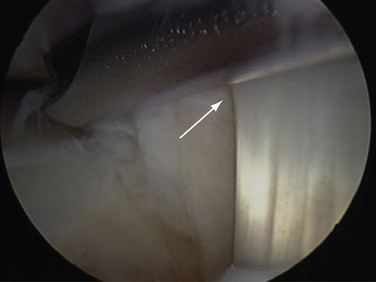

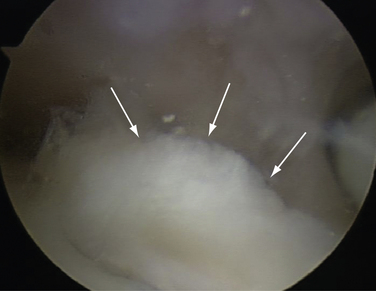

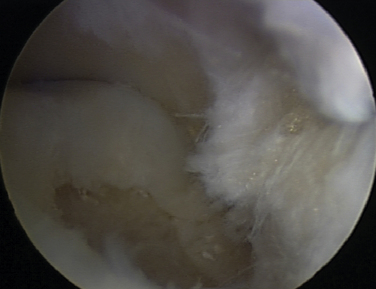

The talar dome and tibial articular surfaces should be inspected. Access to the posterior portion of the dome is obtained by dorsal flexing the ankle to deliver the articular portion posteriorly (Fig. 7-12). An OLT can be addressed. Loose cartilage and bone fragments are mobilized with a blunt spatula and removed with small joint graspers. Microfracturing or drilling of these lesions can be performed as indicated (Fig. 7-13).

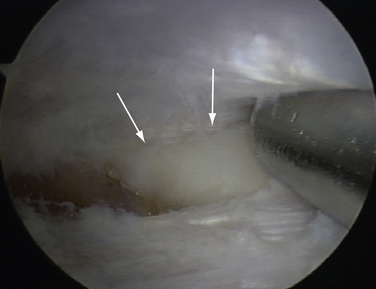

FIGURE 7-12 Arthroscopic view of loose cartilage over a posteromedial osteochondral lesion of the talus (arrows).

FIGURE 7-13 Arthroscopic view after excision of cartilage and bone from the osteochondral lesion of the talus seen in Figure 7-12.

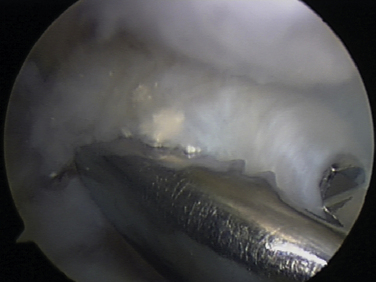

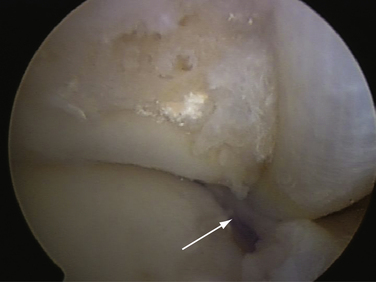

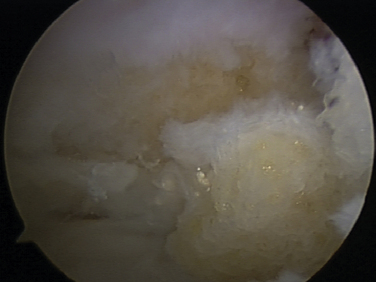

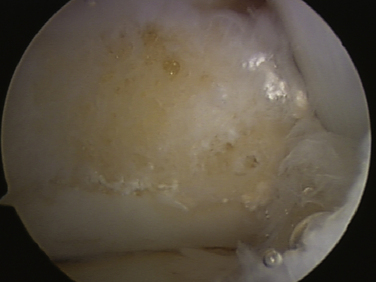

The posterior portion of the talus and tibia is viewed. This is the area of the os trigonum. For patients with os trigonum syndrome, the process is excised. Sharp and dull spatulas are used to mobilize the bone. The fragment is removed through the medial portal (Fig. 7-14). If the piece is large, a pituitary rongeur is used to remove the process in small pieces (Figs. 7-15 and 7-16).

FIGURE 7-14 Arthroscopic view of removal of the bone and fibrous tissue of an os trigonum through the medial portal.

FIGURE 7-16 Arthroscopic view after complete removal of an os trigonum. The subtalar joint can be seen.

The FHL is inspected in the posteromedial joint. Tendonoscopy can be performed to inspect the integrity of the tendon. Tenosynovitis is débrided with a small joint shaver. If there is triggering or constriction of the tendon, the FHL sheath can be released with arthroscopic scissors. The sheath can usually be released to the level of the sustentaculum talus of the calcaneus under direct arthroscopic visualization (Fig. 7-17).

PEARLS& PITFALLS

1. Ferkel RD, Scranton PEJr. Arthroscopy of the ankle and foot. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:1233-1242.

2. Scholten PE, Sierevelt LN, van Dijk CN. Hindfoot endoscopy for posterior ankle impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:2665-2672.

3. van Dijk CN, van Dyk GE, Sholten PE, Kort NP. Endoscopic calcaneoplasty. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:185-189.

4. McGillion S, Cann LB. Posterior ankle arthroscopy. indications, limitations and outcomes, J Bone Joint Surg Br. 91B2009 211 [abstract]

5. Willits K, Sonneveld H, Amendola A, et al. Outcome of posterior ankle arthroscopy for hindfoot impingement. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:196-202.

6. Sitler DF, Amendola A, Bailey CS, et al. Posterior ankle arthroscopy. an anatomic study, J Bone Joint Surg Am. 84A2002 763-769.

7. Yodlowski ML, Scheller ADJr, Minos L. Surgical treatment of Achilles tendinitis by decompression of the retrocalcaneal bursa and the superior calcaneal tuberosity. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:318-321.

8. Watson AD, Anderson RB, Davis WH. Comparison of results of retrocalcaneal decompression for retrocalcaneal bursitis and insertional Achilles tendinosis with calcific spur. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21:638-642.

9. Abramowitz Y, Wollstein R, Barzilay Y, et al. Outcome of resection of a symptomatic os trigonum. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85A:1051-1057.

10. Michelson J, Dunn L. Tenosynovitis of the flexor hallucis longus. a clinical study of the spectrum of presentation and treatment, Foot Ankle Int. 262005 291-303.