Anatomy and disorders of the coccyx

Anatomy of the coccyx

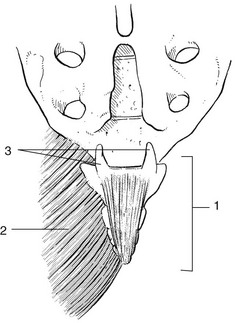

The coccyx is formed by fusion of four rudimentary vertebrae. The first coccygeal vertebra has a base for articulation with the apex of the sacrum and two cornua (cornua coccygea) that are usually large enough to articulate with the cornua sacralia. The sacrococcygeal joint is a true joint with a joint capsule and ligaments. Other ligaments covering the posterior aspect of the coccyx are the posterior intercoccygeal ligaments. The gluteus maximus partly inserts at the dorsolateral aspect of the coccyx via its coccygeal fibres (Fig. 44.1).

The coccyx and overlying skin are innervated via the dorsal rami of S4 and S5.

Disorders of the coccyx

Referred coccygodynia

It is well known that coccygodynia can arise from a lumbar disc lesion, usually as the result of extrasegmental reference.1 Coccygodynia may also arise from irritation of lower pelvic structures (neoplasms of rectum or prostate).2 The history and clinical examination can easily distinguish referred pain from a local disorder. In referred coccygodynia from a disc lesion, pain arises not only during sitting but also during lumbar movements. Coughing is also painful. Physical examination additionally shows pain during lumbar movements, and straight leg raising often increases the discomfort. However, palpation does not assist in diagnosis because local tenderness is to be expected, whichever variety of coccygodynia is present. Tumours or other causes of inflammation affecting the sacrum should be suspected if the pain is not relieved by lying down or if there is nocturnal discomfort. In case of doubt, epidural local anaesthesia can be useful.

Local coccygodynia

In ‘idiopathic’ coccygodynia, no particular injury is noted. It has been suggested that certain anatomical variations of the coccyx predispose to repeated microtraumas, which then cause chronic irritation. A coccyx with a sharp forward angle seems to be more prone to painful stretching.3

Childbirth also causes injury sometimes and postpartum coccygodynia is a well-recognized entity.

Palpation starts at mid-sacrum and four types of coccygodynia may be found:1

• Contusion of the tip of the coccyx and the immediate surrounding tissue. This is the most common type.

• Sprain of the posterior intercoccygeal ligaments.

• Sprain of the sacrococcygeal joint.

• Irritation of the coccygeal fibres of the gluteus maximus muscle. In this condition the pain is unilateral and may spread slightly to one buttock. Occasionally the patient complains that walking is uncomfortable.

Treatment

Steroid infiltration

This can be done if the lesion lies at the tip of the coccyx or when deep friction does not succeed. The injection is usually very effective, but if the patient does not take preventive measures in the form of seating modifications, then relapses may be encountered.4

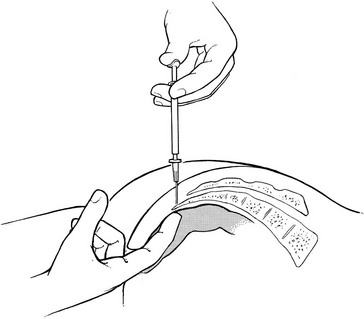

Technique

The patient lies prone on the couch, the pelvis slightly tilted and the legs internally rotated. The tenderness is carefully sought. Sometimes it is necessary to perform rectal palpation (Fig. 44.2). The coccyx is then pressed between the index finger and the thumb. In this position the injection can be given precisely and without fear of penetrating the rectum. This precaution is particularly appropriate if the sacrococcygeal joint or the apex of the coccyx is infiltrated.

Fig 44.2 Steroid infiltration of the coccyx.

Coccygectomy

This is only considered in intractable incapacitating pain persisting in spite of adequate conservative treatment. However, the operation is very rarely indicated and the results are far from good.5,6 Furthermore a high incidence of Gram-negative infection following coccygectomy has been reported.7

Psychogenic coccygodynia

Coccygeal pain may be of psychogenic origin. Because the diagnosis is usually made by eliciting tenderness, the elimination of a psychogenic case is extremely important. Usually the history helps: genuine local coccygodynia does not spread and psychogenic pain is usually vague and radiates in various (impossible) directions. In local coccygodynia, lumbar or hip movements do not elicit pain, whereas they all hurt in a psychogenic case. If suspicion of psychogenic coccygodynia arises, the patient must be given enough freedom during the history and functional examination for contradictions to emerge (see online chapter Psychogenic pain).

References

1. Cyriax, JH, 8th ed. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine; vol I. Baillière Tindall, London, 1982.

2. Traycoff, RB, Crayton, H, Dodson, R, Sacrococcygeal pain syndromes: diagnosis and treatment. Orthopedics. 1989;12(16):1373–1377. ![]()

3. Postachini, F, Massobrio, M, Idiopathic coccygodynia. Analysis of fifty-one operative cases and a radiographic study of the normal coccyx. J Bone Joint Surg 1983; 65:1116–1124. ![]()

4. Kersey, PJ, Non-operative management of coccygodynia. Lancet 1980; 1:318. ![]()

5. Beinhaker, NA, Ranawat, CS, Marchisello, P. Coccygodynia: surgical versus conservative treatment. Orthop Trans. 1977; 1:162.

6. Pyper, JB, Excision of the coccyx for coccygodynia. A study of the results in twenty-eight cases. J Bone Joint Surg 1957; 39B:733–737. ![]()

7. Bayne, O, Bateman, JE, Cameron, HU, Influence of etiology on the results of coccygectomy. Clin Orthop 1984; 190:266–272. ![]()