18 Anaphylaxis

Etiology and Pathogenesis

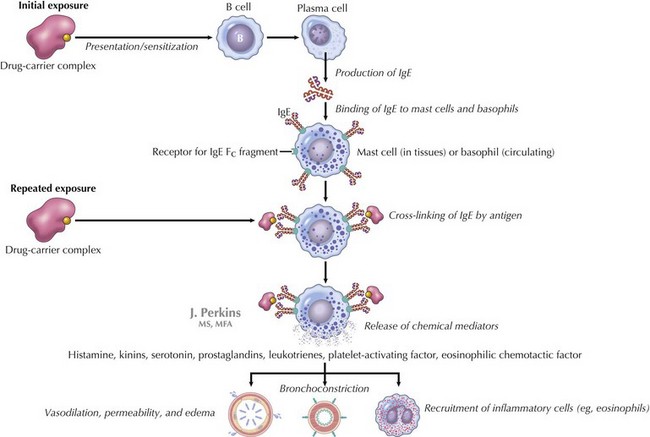

IgE-mediated anaphylaxis, a type I hypersensitivity reaction, is the most understood form of anaphylaxis (Figure 18-1). A person is exposed to an antigen, and upon reexposure, cross-linkage of IgE occurs followed by an immediate release of potent mediators from tissue mast cells and peripheral basophils. These mediators include histamine, leukotrienes, nitric oxide, and neutral proteases, which all lead to vasodilatation, increased vascular permeability, bronchoconstriction, and additional inflammation. At times, the reaction occurs with the first known exposure.

Clinical Presentation

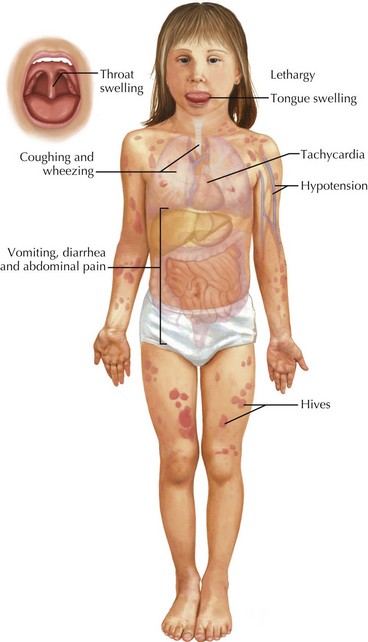

Patients with anaphylaxis may have different clinical manifestations (Table 18-1). Anaphylaxis is often underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed because of clinicians’ failure to recognize symptoms. There has been a recent attempt to standardize the diagnostic criteria to help clinicians to better recognize anaphylaxis (Box 18-1 and Figure 18-2). Approximately 90% of children with allergic reactions have skin manifestations, which include hives, angioedema (see Chapter 20, Figures 20-1 and 20-2), pruritus, or flushing. Although the remainder may not have skin involvement, they are still having a reaction, and that reaction may be more severe than those that occur with skin findings present. Tongue and throat swelling, dysphagia, and choking are manifestations of upper airway edema. Lower respiratory tract symptoms, such as coughing and wheezing, are the next most common symptoms. Vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain are often seen, especially in food-induced anaphylaxis. Cardiovascular manifestations include tachycardia, hypotension, shock, and (rarely) bradycardia. Children may also be lethargic, and some have described a “feeling of impending doom.”

| Systems | Signs and Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Cutaneous |

Box 18-1

Proposed Diagnostic Criteria for Classic Anaphylaxis

Need Any One of Three Criteria to Qualify As Anaphylaxis

Skin mucosal tissue (e.g., hives; generalized itch or flush; swollen lips, tongue, or uvula)

Airway compromise (e.g., dyspnea, wheeze or bronchospasm, stridor, reduced PEF)

Hypotension or associated symptoms (e.g., hypotonia, syncope)

* Low systolic BP for children is defined as <70 mm Hg from 1 month to 1 year; <70 mm Hg + (2× age) from 1 to 10 years; and <90 mm Hg from age 11 to 17 years.

From Sampson HA, Munoz-Furlong A, Bock SA, et al: Symposium of the definition and management of anaphylaxis: summary report. J Allergy Clin Immunol 115:584-591, 2005.

Differential Diagnosis

Given the involvement of multiple organ systems in anaphylaxis, many other life-threatening diagnoses can present similarly (Table 18-2). Vocal cord dysfunction presents with inspiratory stridor and coughing. Wheezing and stridor are also signs of an airway foreign body, croup, bronchiolitis, or an asthma exacerbation. Patients complaining of oral pruritus after food ingestion may have an oral allergy. This is typically self-limited and does not progress to anaphylaxis. Circulatory failure in the form of hypotension, tachycardia, and poor peripheral perfusion may be indicative of a systemic inflammatory response or shock (see Chapter 2). Vasovagal reactions usually present with history of syncope (see Chapter 48). Although urticaria can be an early sign of anaphylaxis, it also is an isolated local cutaneous reaction or may be associated with underlying infection (see Chapter 20). Flushing may occur after ingestion of particular food products, including additives such as monosodium glutamate (MSG) and sulfites, which are found in smoked foods and preservatives. “Red man syndrome” occurs with the use of vancomycin, presents with flushing, and typically resolves with termination of the infusion. Other diagnoses that present with multisystemic involvement include panic attacks, capillary leak syndrome, hereditary angioedema, and systemic mastocytosis. A good history will help distinguish these diagnoses from anaphylactic reactions.

| System | Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Circulatory |

SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

Evaluation and Management

The diagnosis and treatment of anaphylaxis are based on history of event, clinical manifestations, and examination. No diagnostic tests are available that will help to guide management in the immediate setting. However, some diagnostic tests such as serum histamine, urinary histamine, and serum tryptase can be helpful after the acute event (Table 18-3). If performed judiciously and expeditiously, these values can prove useful in supporting the clinical diagnosis of anaphylaxis. Serum histamine levels can be drawn if a patient presents within 1 hour of reaction. β-Tryptase levels are often recommended because they peak 60 to 90 minutes after an anaphylactic reaction and may remain elevated for 6 hours. Positive results are helpful, but a patient may still have had an anaphylactic reaction if results are negative.

| Tests | Marker | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Histamine | Released by mast cells | Serum: within 1 hour of event Urine: methylhistamine can be collected up to 24 hours after event |

| Tryptase (although prefer beta tryptase) | Released by mast cells | Serum: within 6 hours of event (earlier the better) |

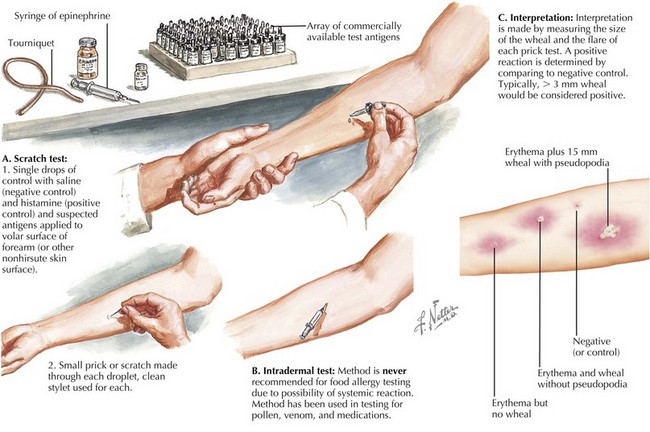

| Skin prick testing | IgE-mediated skin response to specific allergen (only test to a specific allergen) | After exposure (may need to perform 4 weeks after event) |

| Cap RAST | Measures IgE levels in patient’s blood (only test to a specific allergen) | After exposure (may need to perform 4 weeks after event) |

IgE, immunoglobulin E; RAST, radioallergosorbent test.

After someone has a reaction, the cause is then pursued. Often, referral to a specialist is recommended. Knowledge of positive and negative predictive values and sensitivity and specificity of various tests is important. False-positive and false-negative testing can occur; therefore, specific skin prick testing and cap radioallergosorbent testing (RAST) is often useful to confirm one’s suspicion (Figure 18-3). Of note, intradermal testing should never be used for food allergy testing. Intradermal tests are performed for allergies to pollens. The authors do not recommend broad panels of testing; however, if there is a suspicion for a specific food, then the clinician should test accordingly.

Ellis AK, Day JH. Diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis. Can Med Assoc J. 2003;169(4):307-312.

Lieberman PL. Anaphylaxis. Middleton’s Allergy: Principles & Practice. 2009:1027-1049.

Martelli A, Ghiglioni D, Sarratud T, et al. Anaphylaxis in the emergency department: a paediatric perspective. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;8(4):321-329.

Moneret-Vautrin DA, Morisset M, et al. Epidemiology of life-threatening and lethal anaphylaxis: a review. Allergy. 2005;60(4):443-451.

Neugut AI, Ghatak AT, Miller RL. Anaphylaxis in the United States: an investigation into its epidemiology. Arch Intern Med.. 2001;161(1):15-21.

Sampson HA, Munoz-Furlong A, Bock SA, et al. Symposium of the definition and management of anaphylaxis: summary report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:584-591.

Tang AW. A practical guide to anaphylaxis. Am Fam Phys. 2003;68:1325-1332. 1339-1340