Chapter 10 Analysis of NCPAP failures

1 INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) is characterized by intensive snoring and daytime sleepiness, due to repeated obstruction of the upper airway during sleep. OSAS is defined as periods of complete cessation of oronasal airflow for a minimum of 10 seconds (apnea) and periods of more than 30% reduction in oronasal airflow, accompanied by a decrease of more than 4% in ongoing paO2 (hypopnea), with an Apnea/Hypopnea Index (AHI) of more than 5, accompanied by daytime symptoms.1 The prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in the middle-aged is 2% of women and 4% of men.2 It has been estimated that at least 80% of all moderate and severe OSAS in the general population is likely being missed.3

OSAS has adverse effects on daytime quality of life such as daytime sleepiness and diminished intellectual performance. OSAS is of growing significance because of its increasingly recognized high incidence and association with neurocognitive symptoms and cardiovascular disease.4,5 In severe OSAS there is an increased risk of being involved in traffic accidents.6,7 Therefore OSAS is treated for its symptoms, in the attempt to reduce morbidity and mortality.

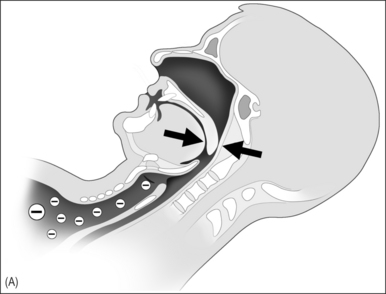

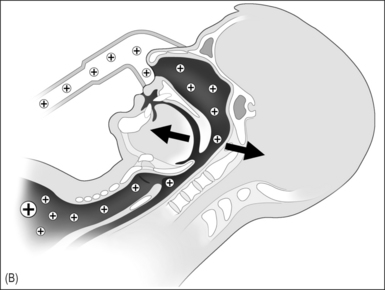

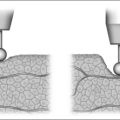

In 1981 nasal continuous positive airway pressure (NCPAP), which acts as a pneumatic splint, was introduced as treatment of OSAS and has been considered the gold standard for treatment of severe OSAS since (Fig. 10.1A & B).8 It is a safe therapeutic option with few contraindications or serious side effects.9 Unfortunately many patients experience NCPAP therapy as intrusive and the acceptance and (long-term) compliance of NCPAP are at best moderate. A vast body of literature was published in the last decade on the subject of (long-term) compliance of NCPAP, with rates ranging from 46% to 89%.10–23 Improvements in NCPAP technology, in particular the introduction of automatic adjustments of the NCPAP pressure throughout the night (auto-CPAP), and attempts to enhance acceptance and compliance have been introduced.24–32 We were interested to see if these actions have led to better acceptance and compliance as compared to earlier reported data.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

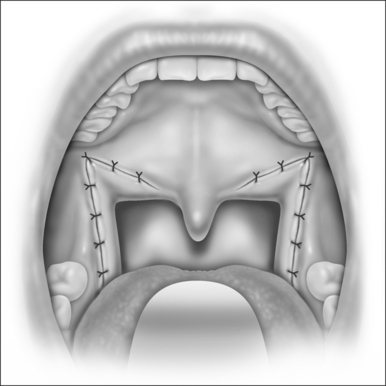

NCPAP has come to be regarded as the gold standard treatment for OSAS in the last decade.33 In the pioneering phase of management of OSAS this view was understandable as uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) was the almost exclusively surgical alternative for OSAS treatment. Metaanalysis by Sher et al. in 1996 showed a success rate of UPPP (in unselected patients) of only 40%.34

Various studies have attempted to analyze compliance. The results vary and do not all apply the same criteria, especially regarding compliance and therapy failure. Furthermore there are no precise recommendations available concerning the necessary duration of daily and weekly use. Twenty-four patients were unavailable for follow-up. Of the remaining 232 patients, 58 (25%) were failures, while 75% were still using NCPAP after 2 months to 8 years of follow-up; 138 (79%) of these 174 patients were considered compliant, as defined above, as compared to 46–89% as reported in earlier series.10–23 Including the 58 failures, only 59.5% of patients can be seen as compliant. There were no statistical differences in compliance between the fixed pressure CPAP and auto-CPAP. Although it was to be expected that patients with a higher AHI and higher Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) would be more compliant, we found no difference for AHI and ESS.

Actual use of NCPAP, as reported in the literature, ranged from 3.7 to 7.2 h in the years 1992 to 2002.11,13,14,16–18,20,22,25,26,33,35–41 These data were usually obtained from fixed NCPAP by time counter registration. The average of NCPAP, both fixed and auto-CPAP, in our series is slightly longer (6.4 h) as compared to the mean of earlier studies (5.4h) on this subject. The number of hours per night of use in our series was, however, estimated by the patient, and therefore it may be that the actual use is lower.

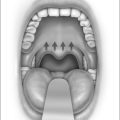

Surgery will not become the first treatment of choice in all patients. However, success rates of UPPP in well-selected patients (obstruction at the retropalatal level only) reach 70–80%.35,36 In patients with obstruction at the retrolingual level comparable success rates have been reported.37 In the light of failure rates for NCPAP therapy it is hard to maintain that NCPAP should always be the treatment of first choice. Therefore, a gradual shift can be expected to take place to alternatives to NCPAP, being a combination of surgery,38,39 and possible positional conditioning,40,41 in well-selected, well-informed patients, while NCPAP therapy in those patients will still be in reserve in case of surgical failure.

1. The Report of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force. Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. Sleep. 1999;22:667-689.

2. Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, et al. The occurrence of sleep disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230-1235.

3. Young T, Evans L, Finn L, Palta M. Estimation of the clinically diagnosed proportion of sleep apnea syndrome in middle-aged men and women. Sleep. 1997;20:705-706.

4. Chesire K, Engleman H, Deary I, et al. Factors impairing daytime performance in patients with sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:538-541.

5. Shamsuzzaman AS, Gersh BJ, Somers VK. Obstructive sleep apnea, implications for cardiac and vascular disease. JAMA. 2003;290:1906-1914.

6. Teran-Santos J, Jimenez-Gomez A, Cordero-Guevara J. The association between sleep apnea and the risk of traffic accidents. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:847-851.

7. George CF, Smiley A. Sleep apnea and automobile crashes. Sleep. 1999;22:790-795.

8. Sullivan CE, Issa FG, Berthon-Jones M, Eves L. Reversal of obstructive sleep apnoea by continuous positive airway pressure applied through the nares. Lancet. 1981;1:862-865.

9. Polo O, Berthon-Jones M, Douglas NJ, Sullivan CE. Management of obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. Lancet. 1994;344:656-660.

10. Sanders MH, Gruendl CA, Rogers RM. Patient compliance with nasal CPAP therapy for sleep apnea. Chest. 1986;90:330-333.

11. Rauscher H, Formanek D, Popp W, Zwick H. Self-reported vs measured compliance with nasal CPAP for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 1993;103:1675-1680.

12. Lojander J, Maasilta P, Partinen M, et al. Nasal-CPAP, surgery, and conservative management for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. A randomized study. Chest. 1996;110:114-119.

13. Hui DS, Choy DK, Li TS, et al. Determinants of continuous positive airway pressure compliance in a group of Chinese patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2001;120:170-176.

14. Sin DD, Mayers I, Man GC, Pawluk L. Long-term compliance rates to continuous positive airway pressure in obstructive sleep apnea: a population-based study. Chest. 2002;121:430-435.

15. Hoffstein V, Viner S, Mateika S, Conway J. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea with nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Patient compliance, perception of benefits, and side effects. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:841-845.

16. Kribbs NB, Pack AI, Kline LR, et al. Objective measurement of patterns of nasal CPAP use by patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:887-895.

17. Krieger J. Long-term compliance with nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in obstructive sleep apnea patients and nonapneic snorers. Sleep. 1992;15:S42-s46.

18. Meurice JC, Dore P, Paquereau J, et al. Predictive factors of long-term compliance with nasal continuous positive airway pressure treatment in sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 1994;105:429-433.

19. Nino-Murcia G, McCann CC, Bliwise DL, et al. Compliance and side effects in sleep apnea patients treated with nasal continuous positive airway pressure. West J Med. 1989;150:165-169.

20. Pepin JL, Krieger J, Rodenstein D, et al. Effective compliance during the first 3 months of continuous positive airway pressure. A European prospective study of 121 patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:1124-1129.

21. Pieters T, Collard P, Aubert G, et al. Acceptance and long-term compliance with nCPAP in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:939-944.

22. Popescu G, Latham M, Allgar V, Elliott MW. Continuous positive airway pressure for sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome: usefulness of a 2 week trial to identify factors associated with long term use. Thorax. 2001;56:727-733.

23. Waldhorn RE, Herrick TW, Nguyen MC, et al. Long-term compliance with nasal continuous positive airway pressure therapy of obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 1990;97:33-38.

24. Fung C, Hudgel DW. A long-term randomized, cross-over comparison of auto-titrating and standard nasal continuous airway pressure. Sleep. 2000;23:645-648.

25. Teschler H, Wessendorf TE, Farhat AA, et al. Two months auto-adjusting versus conventional nCPAP for obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Eur Resp J. 2000;15:990-995.

26. d’Ortho MP, Grillier-Lanoir V, Levy P, et al. Constant vs. automatic continuous positive airway pressure therapy: home evaluation. Chest. 2000;118:1010-1017.

27. Randerath WJ, Schraeder O, Galetke W, et al. Autoadjusting CPAP therapy based on impedance efficacy, compliance and acceptantance. Am J Respir Crit Care med. 2001;163:652-657.

28. Hukins C. Comparative study of autotitrating and fixed-pressure CPAP in the home: a randomized, single-blind crossover trial. Sleep. 2004;27:1512-1517.

29. Massie CA, Hart RW, Peralez K, Richards GN. Effects of humidification on nasal symptoms and compliance in sleep apnea patients using positive airway pressure. Chest. 1999;116:403-408.

30. Duong M, Jayaram L, Camfferman D, et al. Use of heated humidification during nasal CPAP titration in obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:679-685.

31. Mador MJ, Krauza M, Pervez A, et al. Effect of heated humidification on compliance and quality of life in patients with sleep apnea using nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Chest. 2005;128:2151-2158.

32. Hoy CJ, Vennelle M, Kingshott RN, et al. Can intensive support improve continuous positive airway pressure use in patients with sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome? Am j Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1096-1100.

33. Indications and standards for use of nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CAPA) in sleep apnea syndromes. American Thoracic Society. Official statement adopted March 194. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;150:1738–5.

34. Sher AE, Schechtman KB, Piccirillo JF. The efficacy of surgical modifications of the upper airway in adults with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 1996;19:156-177.

35. Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Joseph NJ. Staging of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome: a guide to appropriate treatment. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:454-459.

36. Hessel NS, de Vries N. Resutls of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty after diagnostic work-up with polysomnography and sleep endoscopy; a report of 136 snoring patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;260:19-25.

37. den Herder C, van Tinteren H, de Vries N. Hyoidthyroidpexia: a surgical treatment for sleep apnea syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:740-745.

38. Verse T, Baisch A, Maurer JT, et al. Multilevel surgery for obstructive sleep apnea: Short-term results. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:571-577.

39. Richard W, Kox D, den Herder C, et al. One stage multilevel surgery (uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, Hyoid Suspension, Radiofrequent Ablation of the Tongue Base with/without Genioglossus Advancement) in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264:439-444.

40. Oksenberg A, Silverberg DS, Arons E, Radwan H. Positional versus non-positional obstructive sleep apnea patients. Chest. 1997;112:629-639.

41. Richard W, Kox D, den Herder C. The role of sleep position in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263:946-950.