20.1 Analgesia and sedation

Introduction

Acute pain in children is one of the most common reasons for presentation to the emergency department (ED).1 Pain resulting from injury, illness or necessary medical procedures is associated with increased anxiety, avoidance behaviour, systemic symptoms and parental distress. Painful experiences involve the interaction of physiological, psychological, behavioural, developmental and situational factors. Children with painful conditions can be difficult to assess and are often still underassessed and undertreated. Children often receive less analgesia than adults and the administration of analgesia varies by age, with our youngest patients at the highest risk of receiving inadequate analgesia.2,3

Children’s pain is underestimated because of a lack of adequate assessment tools and the inability to account for the wide range of children’s developmental stages. Pain is often undermedicated because of fears of oversedation, respiratory depression, addiction, and unfamiliarity with use of sedative and analgesic agents in children.3

Assessment and measurement of pain

Pain is a subjective multifactorial experience and should be treated as such.2 Pain may be influenced by age, race, gender, culture, emotional state, cognitive ability, expectations and prior experience. Assessment of pain should be individualised, continuous, measured and documented. Over the last 20 years, pain assessment and measurement tools have been developed that are suitable for children of different ages and developmental stages. A definitive review of pain measurement in infants and children has not been published.

Accurate assessment requires a detailed pain history and consideration of the complexity of the child’s pain perception and the influence of situational, psychological and developmental factors. Because of its subjective nature, pain is best assessed using the child’s self-report, especially in older children’s pain. Observation of the child’s behaviour should be used to complement self-report tools. Four useful means of recognising pain in children are outlined in Table 20.1.2.

Observational assessment scoring may be useful when the child is too young or self-report is not possible, e.g. children with cognitive impairment. Pain ratings provided by parents or regular carers may be used;4 however, whilst there is good correlation between the child’s and the parent’s assessment of pain intensity, parents tend to underscore more severe pain being experienced by their children.5 Physiological measures (e.g. heart rate and respiratory rate) may be useful in pain assessment in non-verbal or sedated children but may be confounded by stress reactions. For example, the infant who is hungry or frightened may give an inappropriately high score.

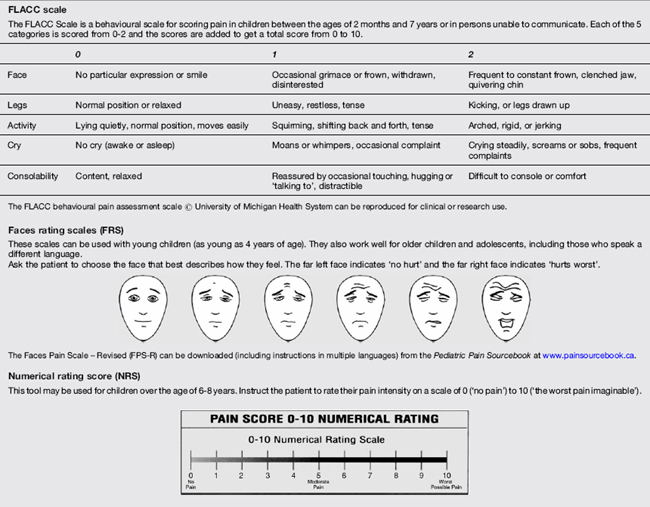

Pain scores are typically standardised on a 0–10 scale. Pain scores are documented with other observations and vital signs. Some common pain rating scales appropriate to age are outlined in Table 20.1.3.

Procedural sedation and analgesia: a structured approach

Critical incident analysis of adverse sedation events in paediatrics has identified inadequate medical evaluation, inadequate monitoring during or after the procedure, inadequate skills in problem recognition and timely intervention and lack of experience of the practitioner with a particular age group or with an underlying medical condition as factors associated with adverse events in paediatric sedation.6

The development and implementation of procedural sedation guidelines in emergency departments, addressing quality of care for the patient, are associated with practice improvements7 and the lessening of adverse events and complications.8–16

The formulation of a sedation plan and sedation policies can be divided into:

While the presence of active asthma or upper respiratory tract infection is associated with a higher risk of complications, including laryngospasm, in patients undergoing general anaesthesia17 it is unclear whether this increased risk also applies to procedural sedation. Most authorities assume that it does and tailor the sedation plans accordingly.

Pre-procedure fasting guidelines are a feature of most protocols developed for procedural sedation in children and aim to minimise the risk of pulmonary aspiration. Both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) list specific fasting times for solids and liquids that vary from 2 hours to 6–8 hours, depending on the age of the child.18,19 However, these recommended times were a result of expert consensus opinion and are not specifically directed at patients in the unique ED setting. In fact, aspiration associated with paediatric procedural sedation has not been reported in the literature and there is no compelling evidence to support specific pre-procedure fasting periods for either liquids or solids.20–23

Whilst some EDs use a general fasting guideline of 2 hours for clear liquids and 4–6 hours for solids or liquids that are not clear (including milk), a number of EDs do not have strict fasting guidelines. The risk of aspiration with ED procedural sedation is likely to be significantly lower than that associated with general anaesthesia and the requirement for fasting remains a subject of debate. Fasting requirements should be adjusted for individual cases, following consideration of an individual patient’s risks of aspiration and the nature and urgency of the sedation.23

The ASA physical status categories developed for general anaesthesia are not generally used for ED procedural sedation as it is unclear how they extrapolate to this setting.24 Following risk assessment and generation of a sedation plan, this plan should be discussed with the child’s parent or carer to obtain informed consent. A clear explanation of the sedation plan and what is to happen for the older child is often useful in an effort to allay anxiety and optimise co-operation.

Medications

Reversal drugs and life-support drugs should also be available (Table 20.1.5).

Intravenous cannulation equipment

a All equipment must be available in varying sizes appropriate to patient population.

b Correct weight-based dose information should be readily available.

Environment

Sedation in environments where the area does not meet these requirements is associated with an increased level of serious adverse events.6

Management during the procedure

A number of recommendations and statements from clinical authorities have been published detailing particular aspects of required personnel, monitoring equipment, patient preparation for procedural sedation in children both inside and outside of the operating theatre.25–27

Accordingly, well-understood policies and procedures detailing the requirements for procedure management should be developed by EDs providing procedural sedation to children. Table 20.1.6 details the important elements of the conduct of procedural sedation management.

Capnography

Capnography provides a more sensitive means of identifying respiratory depression or airway complications resulting from sedative agents than conventional monitoring and observation, but has been underutilised.28

With abnormalities in ventilation that are detectable by capnography and then only later evolve into the typical clinical manifestations of respiratory depression, apnoea, or airway obstruction.29–33 Oxygen desaturation is often the last sign of the complication, particularly when supplemental oxygen has been administered.29

Supplemental oxygen

The use of supplemental oxygen is largely unstudied in children undergoing procedural sedation in the emergency department.32,34,35

The addition of supplemental oxygen has the potential to mask respiratory depression as hypoxia may not manifest even in the presence of significant hypoventilation. Use of ETCO2 monitoring is recommended when supplemental oxygen is administered as changes in ETCO2 associated with respiratory depression are detectable before the onset of hypoxia.34

Sedation scores

These scores are observational in nature and are recorded during the episode of sedation.

A commonly used sedation score is the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin Sedation Scale.9

The scale has seven levels of sedation ranging from 6 to 0:

Deep sedation is commonly defined as a score of 0–2 and moderate sedation as a score of 3.

The Modified Ramsay Sedation Score36 is also commonly used and ranges from a score of 1: awake and alert, through to a maximum score of 8: unresponsive to external stimuli, including pain.

Bispectral index monitoring

The advent of bispectral index (BIS) monitoring to measure the depth of anaesthesia in patients in the operating room may potentially be a useful adjunct in procedural sedation in the ED. 29,37–39

Post-procedure management

The period immediately following the completion of the procedure – with cessation of the painful or unpleasant stimulus – is a period during which cardiorespiratory depressant effects of the sedation drugs may be most apparent and it is during this time that there is an increased risk of complications.40

It is important to have standard discharge criteria, which must be met by the child prior to leaving the ED, and nursing staff caring for the child must be familiar with these. Suggested discharge criteria are listed in Table 20.1.7.

Complications of paediatric procedural sedation

Paediatric procedural sedation can be hazardous and both mortality and significant morbidity have been reported in the literature.41–43

Studies of procedural sedation in EDs with adherence to published guidelines and involvement of staff trained in sedation and paediatric resuscitation techniques have yielded variable rates of complications of 2.3–25%, with the incidence of serious complications such as laryngospasm, pulmonary aspiration or cardio-respiratory arrest being extremely low.43–45

Establishing accurate adverse event and complications rates of different agents from the available literature has been difficult because of the difficulty in aggregating results from previous studies that have used varied terminology to describe the same adverse events and outcomes.46,47

In 2009, a Consensus Panel on Sedation46 proposed a standardised terminology and reporting methodology for adverse events in EDPS in children. Moving away from the traditional event- and threshold-based definitions of an adverse event (e.g. oxygen saturation <92%), the Panel proposed reporting based on whether a particular event required an intervention to be performed by the clinician, i.e. whether the event was clinically relevant rather than simply transient, self-limiting and without clinical sequelae. Adoption of such standardised reporting guidelines by researchers will provide data that may be readily compared and aggregated across a variety of drugs, drug combinations, sedation providers and sedation locations.

The Paediatric Sedation Research Consortium reported on the nature and frequency of adverse events in 30 000 children receiving sedation and/or anaesthesia for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures outside of the operating room.43 The overall reported adverse event rate was 1 in 29 cases (3.4%) and the rate of unplanned treatments was 1 in 89 cases (1.1%) Serious adverse events were rare and there were no deaths. One case of cardiac arrest and one case of pulmonary aspiration were reported. Conversely, more minor but potentially serious adverse events were not rare. Oxygen desaturation below 90% was the most common adverse event reported, with an incidence of 1.5%. Vomiting was common and occurred in 1 in 200 sedations (0.5%). Approximately 1 in 400 procedures were associated with stridor, laryngospasm, wheezing or apnoea and 1 in 200 sedations required airway and ventilation interventions ranging from bag–mask ventilation (0.6%), to oral airway placement (0.3%) to emergency intubation (0.1%). The same research group has also reported the incidence and nature of paediatric sedation with propofol outside the operating room using a large database of 49 836 propofol sedation encounters.44 There were no deaths reported. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was required twice and there were four episodes of pulmonary aspiration. Less serious events were reasonably common, with oxygen desaturation below 90% for more than 30 s having an incidence of 1.5% and apnoea, airway obstruction, wheezing, stridor or laryngospasm occurring at a rate of 1.6%, with a reported rate of unplanned airway interventions (from simple airway manoeuvres to emergency intubation) of 1.5%, which equates to 1 in 70 propofol sedations requiring airway and ventilation interventions.

Metanalyses of predictors of adverse events in procedural sedation with ketamine in children have reported an overall incidence of airway and respiratory adverse events of 3.9% from 8282 episodes of ketamine sedation. The rate of unplanned airway interventions was not reported and many of these observed adverse events required no intervention. The overall incidence of emesis, any recovery agitation, and clinically important recovery agitation was 8.4%, 7.6%, and 1.4%, respectively.45,48

Table 20.1.8 lists adverse events and complications associated with paediatric procedural sedation.

Adherence to published guidelines recommending minimum requirements for personnel, patient monitoring and assessment for safe discharge has been shown to reduce adverse events associated with procedural sedation in children.9

In particular, the generation of an individual sedation plan comprising an individual risk assessment with documentation of variables such as fasting status, quantitative sedation scoring, time-based recording of vital signs and pulse oximetry combined with standardised recovery and discharge criteria and use of a standardised record has been shown to progressively reduce risk in procedural sedation, particularly in those children requiring a deep level of sedation.9

Non-pharmacological methods

A balanced multidisciplinary approach using pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies is essential to providing optimal analgesia and sedation for the child. Non-pharmacological techniques can be particularly useful in pain management (whether or not medications are used as well) as they are free of side effects and may be utilised before, during and after painful procedures. The planning of procedures for children in the ED should include age-appropriate psychological interventions, such as distraction techniques. Distraction reduced self-reported pain following needle-related procedural pain.49 Age-appropriate distraction techniques reduced situational anxiety in older children and lowered parental perception of distress in younger children undergoing laceration repair.50 A child’s anxiety and co-operation are affected by age, anxiety of the parent and previous medical experiences. Toddlers are very distractible and storytelling and guided imagery are very effective methods. Some useful non-pharmacological strategies are outlined in Table 20.1.9.

Pharmacological methods

Some of the most commonly used agents are listed in Table 20.1.10.

N2O continuous flow variable mix 30–70% with oxygen

LA, local anaesthetic; IM, intramuscular; IN, intranasal; IV, intravenous; PO, per oram; PR, per rectum.

Oxycodone and codeine

Oral codeine has traditionally been used for moderate to severe pain; however, evidence from recent work shows that oral oxycodone produces greater pain relief compared with codeine.51Oxycodone also has a better side effect profile with less itching, less nausea, and fewer allergic reactions. Codeine is a prodrug of morphine and nine percent of children do not have the liver enzyme CYP2D6 to convert the inactive codeine and therefore in this group it provides no analgesia.

Oral sucrose for infant analgesia

Oral sucrose (25%) has been shown to be a simple, safe and effective means of providing analgesia for young infants (up to 2 months of age) for short painful events (e.g. venepuncture, lumbar puncture).52–54 It stimulates endogenous opioid and non-opioid pathways in the brain. Up to 2 mL may be administered via oral syringe or on a pacifier approximately 2 minutes prior to the painful event.

Intranasal fentanyl

Intranasal fentanyl provides safe and effective analgesia equivalent to parenteral morphine in children as young as 1 year of age.55–58 It offers a quicker onset, is less invasive, and its duration of action, although short, allows time for topical anaesthetic application prior to intravenous cannulation for ongoing analgesia. It is particularly useful for analgesia for fractures or burns dressings but its utilisation is spreading into other areas.

Nitrous oxide

Nitrous oxide mixed with oxygen has a potent analgesic action with rapid onset and offset. It is an excellent analgesic sedative for gaining rapid IV access, injecting local anaesthetics, performing a nerve block or splinting a fractured limb.59–61

Entonox® (50% nitrous oxide, 50% oxygen) is usually delivered via a demand-valve system. This limits its use in younger or unco-operative children. Machines that deliver variable concentration (30–70%) nitrous oxide via a continuous flow system allow the use of this agent down to age 1 year, where it has been shown to be safe when embedded in a comprehensive sedation programme.61

Nitrous oxide alone is effective in achieving moderate levels of procedural sedation for a high percentage of children with painful conditions but may require the use of adjunctive analgesics for very painful procedures.61,62

Ketamine

Ketamine is a unique analgesic dissociative agent. Its action produces a near ideal state of sedation, amnesia, analgesia and motion control with few side effects. It has been extensively studied, with safety and efficiency documented in several large paediatric studies. It is particularly suitable for laceration repair and orthopaedic procedures in the emergency department. Emergence reactions, common in adults during the recovery phase, are rare in children. Co-administration of midazolam has not been shown to reduce the rate of emergence phenomena but may be associated with less post-procedure emesis. Intravenous ondansetron significantly reduces the incidence of vomiting associated with ketamine sedation.63

Airway complications (including stridor, laryngospasm, respiratory depression, and apnoea) very rarely occur and have been reported as being associated with high intravenous dosing (initial dose >2.5 mg kg−1 or total dose ≥5.0 mg kg−1), administration to children younger than 2 years or aged 13 years or older, and the use of co-administered anticholinergics or benzodiazepines.45 There are few data on EDPS in relation to infants under the age of 3 months and the traditional contraindication to ketamine in this age group should continue until there is evidence of safety in this group.

Multiple routes of administration are available but IV and IM routes are preferred.

Both routes display similar risk of airway and respiratory adverse events, and of clinically important recovery agitation. The IM route is associated with a higher rate of vomiting.45,48

Comprehensive ketamine clinical practice guidelines were published in 2004.64,65

Methoxyflurane

A recent review has shown that the inhalational agent Methoxyflurane, long used by ambulance services, is also safe and effective in the ED setting.66 The commonly-used ‘Penthrox’ inhaler is now available with an activated charcoal scavenging chamber to reduce environmental contamination.

Propofol

Propofol is an excellent ultra-short acting sedative/hypnotic agent, very useful for EDPS. It provides deep sedation and has anti-emetic and euphoric properties. Propofol has no analgesic properties and therefore needs adjunctive analgesic agents, e.g. fentanyl or ketamine when used for procedural analgesia and sedation (PSA) for short painful procedures. Used alone, it is effective in producing co-operation for painless diagnostic studies in emergency department patients. When combined with opiate agents, it has been used effectively for painful procedures in children (e.g. fracture reduction). It is associated with a significantly higher rate of adverse airway events (oxygen desaturation and need for airway repositioning) when compared to ketamine,67 emphasising the importance of having skilled and experienced practitioners available when it is being used.

It does offer quick recovery to pre-sedation state, allowing more rapid discharge. It may be delivered in a variety of manners from repeated boluses to continuous infusion. Despite initial barriers to the use of propofol in the ED, a large number of studies have produced evidence that propofol can be given in a safe and effective manner in ED for children.68–72 Titrating and optimising the dose will enhance control of depth of sedation and recovery time.73 Predictable cardiovascular and respiratory events respond to repositioning the airway, increasing oxygen delivery or limited BVM-assisted ventilation without adverse sequelae.73 Capnography is now considered essential for early detection of hypopnoea and apnoea.31

An evidence-based Clinical Practice Advisory describing propofol use in EDPS was published in 2007.74

Ketafol

Ketafol refers to a mixture of ketamine/propofol in a 1:1 ratio (i.e. 1 mg ketamine: 1 mg propofol). A median dose of 0.75 mg kg−1 of each drug (range 0.2–2.0) has been shown to be safe and effective for procedural sedation in children.75 Fentanyl is usually used as adjunctive analgesia but a study looking at combining propfol with a sub-dissociative dose of ketamine (0.3 mg kg−1 IV) compared with fentanyl suggested that the ketamine/propofol combination was safer.76 Further research is required to determine if combining the two agents together is associated with fewer cardiovascular and respiratory adverse effects than using propofol alone.77

Local and topical anaesthetic agents

The expanded use of topical anaesthetics has revolutionised the management of simple lacerations in the ED and has also greatly improved conditions for intravenous cannulation and lumbar puncture. These agents provide a non-invasive means of producing local anaesthesia and can be applied at triage to facilitate timely management in the ED.78

EMLA® (2.5% lidocaine, 2.5% prilocaine) is a well-established topical anaesthetic for use on intact skin prior to venepuncture, intravenous cannulation or lumbar puncture. Its use in the ED is, however, limited, due to its long onset to peak effect (at least one hour) and its vasoconstrictive effect, which may make cannulation more difficult. EMLA® has a theoretical risk of methaemoglobinaemia and is not recommended in infants less than 3 months of age.79

Amethocaine (e.g. AnGel® – 4% amethocaine) has a quicker onset of action (30–45 minutes) than EMLA® and its vasodilating effect may facilitate cannulation. Tetracaine is superior to EMLA® in terms of lessening pain associated with intravenous cannulation and is more effective than EMLA® when application time is less than 60 minutes.80

Itching and erythema are side effects of tetracaine, whilst skin blanching is seen with EMLA® as a consequence of vasoconstriction.80

Topical wound anaesthetics, e.g. Laceraine® (adrenaline [epinephrine] 1:1000, lidocaine 4%, tetracaine 0.5%) and Adrenaline Cocaine Gel (adrenaline 1:1000, cocaine 12%) permit wound management with minimal to no discomfort.81,82

Cocaine-containing topical wound anaesthetics (e.g. TAC – tetracaine, adrenaline, cocaine) were originally found to be very effective in providing good wound anaesthesia but non-cocaine-containing topical wound anaesthetics have now been shown to be equivalent or superior to cocaine-containing preparations, Such preparations are significantly cheaper, are not associated with the requirement for secure storage and avoid the potentially serious systemic side effects that have been reported with cocaine-containing preparations.83–85

Local anaesthetic combination solutions such as Laceraine® instilled in a wound for 20–30 minutes provide sufficient anaesthesia for suturing 75–90% of scalp and facial lacerations82,86 and 40–60% of extremity wounds. Its vasoconstrictive effect is also useful prior to application of cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive.

Wound infiltration with injectable local anaesthetics can be carried out with lessened pain by buffering the local anaesthetic, warming the solution to body temperature, using fine-bore needles and slow administration techniques through the wound edges rather than through intact skin.87–91 Nitrous oxide and distraction techniques during the process of injection often provide good analgesia. Safe dosage regimes must be adhered to by the clinician.

Regional anaesthetic techniques

Regional nerve blocks may be used for either pain relief (e.g. femoral nerve block for femur fracture) or to facilitate suturing, fracture or dislocation reduction (e.g. digital or metacarpal blocks).79,92 Nerve blocks have traditionally been performed using anatomical landmarks, with variable results. The use of ultrasound has been shown to increase the success of regional anaesthetic techniques. Intravenous regional anaesthesia (Bier’s block) is useful and effective for some older children. Tired children, reluctant children, parental concern, or the lack of ED resources may make deep sedation or a general anaesthetic the preferred approach.

Discharge analgesia

Lack of appropriate or inadequate dosing of discharge analgesia is an ongoing problem. Pain experienced at home post acute injury or PSA in the ED can place considerable extra burden on family physicians for pain- related issues. It is essential to include adequate discharge analgesia in ED pain management guidelines. Ibuprofen was found to be preferable to paracetamol and codeine for outpatient management for children with uncomplicated arm fractures.93

Selection of agents by procedure and age

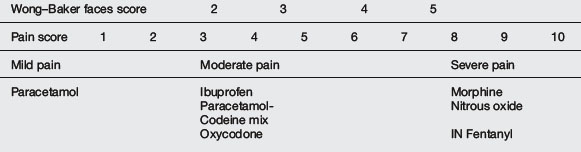

Pain management can be simplified by dividing pain into mild, moderate and severe categories and matching this with the appropriate analgesic agent(s) (Table 20.1.11). It is best to minimise the number of agents used and to be familiar with doses, duration of action, adverse effects and contraindications. Choice of agent should be individualised for the child’s level of pain and the procedure. Dissociative techniques using various combinations of agents are useful for very painful procedures or in infants and toddlers.

Ideally, routes of administration should be non-invasive. Extensive knowledge and experience of the synergistic effects of analgesics and sedative agents can produce a ‘balanced’ state of sedation and analgesia (Table 20.1.12).

| The four components |

Recommendations for some common procedures

Nasogastric tube insertion

Although nebulised lidocaine has been shown to be a useful analgesic method for this distressing procedure in adults, it has been shown to be ineffective in children.94 Oral sucrose may be useful in neonates requiring nasogastric tubes. Topical Cophenylcaine Forte® may help alleviate pain, lessen epistaxis and assist passage of the tube by decreasing swelling.

Multi-trauma

Controversies and Future Directions

The future for clinical practice in the area of analgesia and sedation for children will focus on making our practices safer, more time efficient for the ED and less distressing for the child. Consensus-based recommendations for standardising the terminology used for reporting adverse events related to paediatric emergency department procedural sedation have recently been published.46 These should help to create a uniform reporting mechanism for future studies in this area.

The future for clinical practice in the area of analgesia and sedation for children will focus on making our practices safer, more time efficient for the ED and less distressing for the child. Consensus-based recommendations for standardising the terminology used for reporting adverse events related to paediatric emergency department procedural sedation have recently been published.46 These should help to create a uniform reporting mechanism for future studies in this area. Development of guidelines with greater attention paid to selection of appropriate patients, provision of adequate facilities and training of staff (as outlined earlier in this chapter) will further improve the safety profile of our practices. Clinical audit of sedation/analgesia practice should be routine. Our practices will be made more efficient by future research to help define the optimal agent(s) and route of administration for particular procedures and patient age groups.

Development of guidelines with greater attention paid to selection of appropriate patients, provision of adequate facilities and training of staff (as outlined earlier in this chapter) will further improve the safety profile of our practices. Clinical audit of sedation/analgesia practice should be routine. Our practices will be made more efficient by future research to help define the optimal agent(s) and route of administration for particular procedures and patient age groups.1 Maurice S.C., O’Donnell J.J., Beattie T.F. Emergency analgesia in the pediatric population. Part 1, Current practice and perspectives. J Emerg Med. 2002;19:4-7.

2 American Academy of Pediatrics, Society, A. P. The assessment and management of acute pain in infants, children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2001;108:793-797.

3 Zempsky W.T., Cravero J.P., Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine, and Section on Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine. Relief of pain and anxiety in pediatric patients in emergency medical systems. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1348-1356.

4 Wilson G.A., Doyle E. Validation of three paediatric pain scores for use by parents. Anaesthesia. 1996;51:1005-1007.

5 Kelly A.M., Powell C.V., Williams A. Parent visual analogue scale ratings of children’s pain do not reliably reflect pain reported by child. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18:159-162.

6 Cote C.J., Notterman D.A., Karl H.W., et al. Adverse sedation events in pediatrics: A critical incident analysis of contributing factors. Pediatrics. 2000;105:804-814.

7 Priestley S., Babl F., Krieser D., et al. Evaluation of the impact of a paediatric procedural sedation credentialing programme on quality of care. Emerg Med Australas. 2006;18:498-504.

8 Nicol M.F. Risk management audit: Are we complying with the national guidelines for sedation by non-anaesthetists? J Accid Emerg Med. 1999;16:120-122.

9 Hoffman G.M., Nowakowski R., Troshynski T.J., et al. Risk reduction in pediatric procedural sedation by application of an American Academy of Pediatrics/American Society of Anesthesiologists Process Model. Pediatrics. 2002;109:236-243.

10 Schneeweiss S., Ratnapalan S. Impact of a multifaceted pediatric sedation course: self-directed learning versus a formal continuing medical education course to improve knowledge of sedation guidelines. Can J Emerg Med Care. 2007;9:93-100.

11 Shavit I., Steiner I.P., Idelman S., et al. Comparison of adverse events during procedural sedation between specially trained pediatric residents and pediatric emergency physicians in Israel. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:617-622.

12 Ratnapalan S., Schneeweiss S. Guidelines to practice: the process of planning and implementing a pediatric sedation program. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:262-264.

13 Babl F., Priestley S., Kreiser D., et al. Development and implementation of an education and credentialing programme to provide safe paediatric procedural sedation in emergency departments. Emerg Med Australas. 18, 2006.

14 Shavit I., Keidan I., Hoffmann Y., et al. Enhancing patient safety during paediatric sedation: The impact of simulation-based training of non-anaesthesiologists. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:740-743.

15 Borland M., Esson A., Babl F., Krieser D. Procedural sedation in children in the emergency department: A PREDICT study. Emerg Med Australas. 2009;21:71-79.

16 Everitt I., Younge P., Barnett P. Paediatric sedation in EDs: What is our practice? Emerg Med Australas. 2002;14:62-66.

17 Olsson G.L., Hallen B. Laryngospasm during anaesthesia – a computer-aided incidence study in 136,929 patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1984;28:567-575.

18 American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, Cote C.J., Wilson S., the Workgroup on Sedation. Guidelines for monitoring and management of pediatric patients during and after sedation for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures: an update. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2587-2602.

19 American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1004-1017.

20 Green S.M., Krauss B. Pulmonary aspiration risk during ED procedural sedation – An examination of the role of fasting and sedation depth. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:35-42.

21 Agrawal D., Manzi S.F., Gupta R., Krauss B. Preprocedural fasting state and adverse events in children undergoing procedural sedation and analgesia in a pediatric emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:636-646.

22 Roback M.G., Bajaj L., Wathen J.E., Bothner J. Preprocedural fasting and adverse events in procedural sedation and analgesia in a pediatric emergency department: Are they related? Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:454-459.

23 Green S.M., Roback M.G., Miner J.R., et al. Fasting and emergency department procedural sedation and analgesia: a consensus-based clinical practice advisory. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:454-461.

24 American Society of Anaesthesiologists. Manual for Anaesthesia Department Organization and Management. 2001.

25 Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists Policy Statement 9 (Review). Guidelines on Sedation and/or Analgesia for Diagnostic and Interventional Medical or Surgical Procedures. 2008. http://www.anzca.edu.au/resources/professional-documents/pdf/PS9-2010.pdf [accessed 08.03.11]

26 Mace S.E., Brown L.A., Francis L., et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the sedation of pediatric patients in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:378-399.

27 Steven A., Godwin M.D., David A., et al. Clinical policy: Procedural sedation and analgesia in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45:177-196.

28 Langhan M.L., Chen L. Current utilization of continuous end-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring in pediatric emergency departments. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24:211-213.

29 Green S.M. Research Advances in Procedural Sedation and Analgesia. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:31-36.

30 Burton J.H., Harrah J.D., Germann C.A., et al. Does end-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring detects respiratory events prior to current sedation monitoring practices? Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:500-504.

31 Anderson J.L., Junkins E., Pribble C., Guenther E. Capnography and depth of sedation during propofol sedation in children. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:9-13.

32 Krauss B., Hess D.R. Capnography for procedural sedation in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:172-181.

33 Miner J., Heegaard W., Plummer D. End–tidal carbon dioxide monitoring during procedural sedation. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:275-280.

34 Deitch K., Chudnofsky C.R., Dominici P. The utility of supplemental oxygen during emergency department procedural sedation and analgesia with midazolam and fentanyl: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:1-9.

35 Deitch K., Chudnofsky C.R., Dominici P. The utility of supplemental oxygen during emergency department procedural sedation with propofol: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:1-8.

36 Gill M., Green S.M., Krauss B. A study of the bispectral index monitor during procedural sedation and analgesia in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:234-241.

37 Agrawal D., Feldman H.A., Krauss B., Waltzman M.L. Bispectral index monitoring quantifies depth of sedation during emergency department procedural sedation and analgesia in children. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:247-255.

38 Fatovich D.M., Gope M., Paech M.J. A pilot trial of BIS monitoring for procedural sedation in the emergency department. Emerg Med Australas. 2004;16:103-107.

39 Dominguez T.E., Helfaer M.A. Review of bispectral index monitoring in the emergency department and pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22:815-821.

40 Krauss B., Green S.M. Primary care: Sedation and analgesia for procedures in children. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:938-945.

41 Yaster M., Nichols D.G., Deshpande J.K., et al. Midazolam-fentanyl intravenous sedation: Case report of respiratory arrest. Pediatrics. 1990;86:463-467.

42 Jastak J.T., Pallasch T. Death after chloral hydrate sedation: Report of case. J Am Dent Assoc. 1988;116:345-348.

43 Cravero J.P., Blike G.T., Beach M., et al. Incidence and nature of adverse events during paediatric sedation/anesthesia for procedures outside the operating room: Report From the Paediatric Sedation Research Consortium. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1087-1096.

44 Cravero J.P., Beach M., Blike G.T., et al. Incidence and nature of adverse events during paediatric sedation/anesthesia with propofol for procedures outside the operating room: A Report From the Paediatric Sedation Research Consortium. Anesth Analg. 2009;1083:795-804.

45 Green S.M., Roback M.G., Krauss B., et al. Predictors of airway and respiratory adverse events with ketamine sedation in the emergency department: an individual- patient data meta-analysis of 8282 children. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:158-168.

46 Bhatt M., Kennedy R.M., Osmond M.H., et al. Consensus-based recommendations for standardizing terminology and reporting adverse events for emergency department procedural sedation and analgesia in children. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:426-435.

47 Green S.M., Yealy D.M. Procedural sedation goes Utstein: the Quebec guidelines. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:436-468.

48 Green S.M., Roback M.G., Krauss B., et al. Predictors of emesis and recovery agitation with emergency department ketamine sedation: an individual-patient data meta-analysis of 8,282 children. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:171-180.

49 Uman L.S., Christine T., Chambers P., et al. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials examining psychological interventions for needle related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents: An Abbreviated Cochrane Review. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:842-854.

50 Sinha M., Christopher N.C., Fenn R., Reeves L. Evaluation of nonpharmacologic methods of pain and anxiety management for laceration repair in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1162-1168.

51 Charney R.L., Yan Y., Schootman M., et al. Oxycodone versus codeine for children with suspected forearm fracture: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;9:595-600.

52. Stevens B, Yamada J, Ohlsson A. Sucrose for analgesia in newborn infants undergoing painful procedures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:CD001069

53 Le Frak L., Knoerlein N., Duncan J., et al. Sucrose analgesia: Identifying potentially better practices. Paediatrician. 2006;118:197-202.

54 Carbajal R., Verapen S., Coudere S. Analgesic effect of breast feeding In term neonates: randomised controlled trial. Br Med J. 2003;326:13.

55 Cole J., Shepherd M., Young P. Intranasal fentanyl in 1-3-year-olds: a prospective study of the effectiveness of intranasal fentanyl as acute analgesia. Emerg Med Australas. 2009;21:395-400.

56 Borland M., Jacobs I., King B., O’Brien D. A randomized controlled trial comparing intranasal fentanyl to intravenous morphine for managing acute pain in children in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:335-340.

57 Borland M.L., Bergesio R., Pascoe E.M., et al. Intranasal fentanyl is an equivalent analgesic to oral morphine in paediatric burns patients for dressing changes: a randomised double blind crossover study. Burns. 2005;31:831-837.

58 Borland M.L., Jacobs I., Geelhoed G. Intranasal fentanyl reduces acute pain in children in the emergency department: a safety and efficacy study. Emerg Med Australas. 2002;14:275-280.

59 Kanagasundaram S.A., Lane L.J., Cavalletto B.P., et al. Efficacy and safety of nitrous oxide in alleviating pain and anxiety during painful procedures. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84:492-495.

60 Gall O., Annequin D., Benoit G., et al. Adverse events of premixed nitrous oxide and oxygen for procedural sedation in children. Lancet. 2001;358:1514-1515.

61 Babl F.E., Oakley E., Seaman C., et al. High-concentration nitrous oxide for procedural sedation in children: adverse events and depth of sedation. Pediatrics. 2008;121:528-532.

62 Babl F.E., Oakley E., Puspitadewi A., et al. Limited analgesic efficacy of nitrous oxide for painful procedures in children. Emerg Med J. 2008;25:717-721.

63 Langston W.T., Wathen J.E., Roback M.G., Bajaj L. Effect of ondansetron on the incidence of vomiting associated with ketamine sedation in children: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:30-34.

64 Mace S.E., Barata I.A., Cravero J.P., et al. Evidence-based approach to pharmacologic agents used in pediatric sedation and analgesia in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44(342):377.

65 Green S.M., Krauss B. Clinical practice guideline for emergency department ketamine dissociative sedation in children. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:460-471.

66 Grindley J., Babl F.E. Review article: Efficacy and safety of methoxyflurane analgesia in the emergency department and prehospital setting. Emerg Med Australas. 2009;2:4-11.

67 Migita R.T., Klein E.J., Garrison M.M. Sedation and analgesia for pediatric fracture reduction in the emergency department: a systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:46-51.

68 Bell A., Treston G., Cardwell R., et al. Optimization of propofol dose shortens procedural sedation time, prevents resedation and removes the requirement for post-procedure physiologic monitoring. Emerg Med Australas. 2007;19:411-417.

69 Burton J.H., Miner J.R., Shipley T.D., et al. Propofol for emergency department procedural sedation and analgesia: a tale of three centers. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:24-30.

70 Green S.M. Propofol in emergency medicine: further evidence of safety. Emerg Med Australas. 2007;19:389-393.

71 Patel D.K., Keeling P.A., Newman G.B., Radford P. Induction dose of propofol in children. Anaesthesia. 2007;43:949-952.

72 Hohl C.M., Mohsen S., Nosyk B., et al. Safety and clinical effectiveness of midazolam versus propofol for procedural sedation in the emergency department: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:1-8.

73 Bell A., Treston G., McNabb C., et al. Profiling adverse respiratory events and vomiting when using propofol for emergency department procedural sedation. Emerg Med Australas. 2007;19:405-410.

74 Miner J.R., Burton J.H. Clinical practice advisory: Emergency department sedation with propofol. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:182-187.

75 Willman E.V., Andolfaltto G. A prospective evaluation of ‘kefofol (ketamine/propofol combination) for procedural sedation & analgesia in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:23-30.

76 Messenger D.W., Murray H.E., Dungey P.E., et al. Subdissociative-dose ketamine versus fentanyl for analgesia during propofol procedural sedation: a randomized clinical trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;16:877. 866

77 Arora S. Combining ketamine and propofol (“Ketofol”) for emergency department procedural sedation and analgesia: a review. West J Emerg Med. 2008;9:20-23.

78 Priestley S.J., Kelly A.M., Chow L., et al. Application of topical local anesthetic at triage reduces treatment time for children with laceration: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:34-40.

79 Barnett P. Alternatives to sedation for painful procedures. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25:415-419.

80 Lander J.A., Welman B.J., S S.S. EMLA and amethocaine for reduction of children’s pain associated with needle insertion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006. 10.1002/14651858.CD004236.pub2. Art. No.: CD004236

81 Dart C. Comparison of lignocaine 1% injection and adrenaline-cocaine gel for local anaesthesia in repair of lacerations. Emerg Med Australas. 1998;10:38-44.

82 Schilling C.G., Bank D.E., Borchert B.A., et al. Tetracaine, epinephrine (adrenalin), and cocaine (TAC) versus lidocaine, epinephrine and tetracaine (LET) for anesthesia of laceration in children. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;2(5):203-208.

83 Eidelman A., Weiss J.M., Enu I.K., et al. Comparative efficacy and costs of various topical anaesthetics for repair of dermal lacerations: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. J Clin Anesth. 2005;17:106-116.

84 Barnett P. Cocaine toxicity following dermal application of adrenaline-cocaine preparation. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1998;14:280-281.

85 Daya M.R., Burton B.T., Schleiss M.R., et al. Recurrent seizures following mucosal application of TAC. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:646-648.

86 Ernst A.A., Marvez E., Nick T.G., et al. Lidocaine adrenaline tetracaine gel versus tetracaine adrenaline cocaine gel for topical anesthesia in linear scalp and facial laceration in children aged 5 to 17 years. Pediatrics. 1995;95:255-258.

87 Mader T.J., Playe S.J., Garb J.L. Reducing the pain of local anesthetic infiltration: Warming and buffering have a synergistic effect. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:550-554.

88 Bartfield J.M., Gennis P., Barbera J., et al. Buffered versus plain lidocaine as a local anesthetic for simple laceration repair. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19:1387-1390.

89 Scarfone R.J. Pain of local anesthetics: Rate of administration and buffering. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31:36-40.

90 Kelly A.M., Cohen M., Richards D. Minimizing the pain of local infiltration anesthesia for wounds by injection into the wound edges. J Emerg Med. 1994;12:593-595.

91 Davies R.J. Buffering the pain of local anaesthetics: A systematic review. Emerg Med Australas. 2003;15:81-88.

92 Peutrell J.M., Mather S.J. Regional Anaesthesia in Babies & Children. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

93 Drendel A.L., Gorelick M.H., Weisman S.J., et al. A randomized clinical trial of ibuprofen versus acetaminophen with codeine for acute pediatric arm fracture pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:553-560.

94 Babl F.E., Goldfinch C., Mandrawa C., et al. Does nebulized lidocaine reduce the pain and distress of nasogastric tube insertion in young children? A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1548-1555.

Cote C.J., Notterman D.A., Karl H.W., et al. Adverse sedation events in pediatrics: A critical incident analysis of contributing factors. Paediatrics. 2000;105:804-814.

Green S.M. Research advances in procedural sedation and analgesia. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:31-36.

Green S.M., Krauss B. Pulmonary aspiration risk during ED procedural sedation – An examination of the role of fasting and sedation depth. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:35-42.

Mace S.E., Brown L.A., Francis L., et al. Clinical policy: Critical issues in the sedation of pediatric patients in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:378-399.

Paediatrics & Child Health Division, The Royal Australasian College of Physicians. Guideline Statement: Management of procedure-related pain in children and adolescents. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006;42:S1-S29.