Chapter 21 ANAL PAIN

CAUSES OF ANAL PAIN

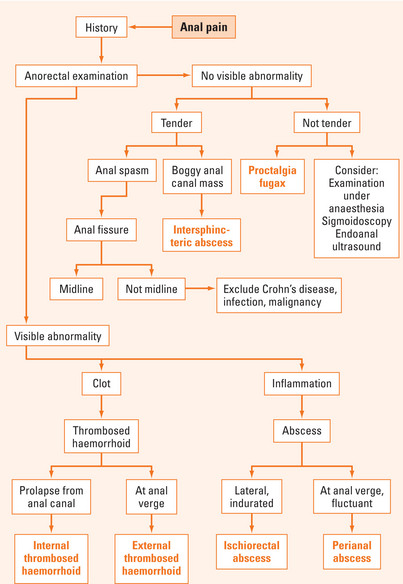

There are many causes of anal pain (Table 21.1). Patients usually attribute anal pain to haemorrhoids. However, haemorrhoids rarely cause pain unless they are complicated by prolapse and thrombosis. There is usually some delay in presentation because of patient embarrassment. A thorough history and careful examination can usually elicit the diagnosis without need for further investigations (Figure 21.1). Occasionally, other investigations are required and may include examination under anaesthesia, biopsy and pathological analysis, sigmoidoscopy, endoanal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

| Frequency | Causes |

| Common |

Anal fissure

Anal fissure is caused by a tear in the mucosa of the anal canal, usually from a hard stool. It causes anal pain worse on defecation, lasting for several hours and associated with a small amount of bright red rectal bleeding. Physical examination may reveal the triad of internal anal papilloma, anal fissure and external sentinel skin tag. Sphincter muscle is present in the base of the fissure. Of all anal fissures, 90% are located in the posterior region, 5% in the anterior region and 5% in other areas. When an anal fissure is not situated in the posterior or anterior positions, a secondary aetiological factor (e.g. Crohn’s disease, infection or malignancy) should be entertained. Delay in healing of anal fissures has been attributed to impaired blood supply, demonstrated on ultrasound Doppler studies and postmortem studies.

Anorectal abscess/fistula

Anal fistula is a tract from the anal canal to the perianal skin. They are classified as intersphincteric, transsphincteric (most common), suprasphincteric and extrasphincteric. Patients with anal fistulas present with persistent discharge of pus and/or blood from the external opening. If the external opening closes over, recurrent abscess formation will occur. Assessment of anal fistulas includes identifying the internal and external openings, the primary track, secondary extensions, and other associated diseases.

Treatment of anal fistula involves defining the anatomy, draining associated sepsis, eradicating the fistula, preventing recurrence and preserving continence. The best treatment of low anal fistulas is fistulotomy. Fistulotomy involves laying open the fistula tract to allow healing by secondary intention. If the fistula is high, more sphincter muscle is involved and division would result in incontinence. Females are at higher risk of faecal incontinence because they have shorter anal sphincter lengths than males and may have sustained occult obstetric sphincter injuries. There are many operations available for high fistula-in-ano, each with varying cure and incontinence rates (Table 21.2). The best treatment is probably mucosal advancement flap, which has high cure and low incontinence rates.

| Treatment | Cure rate | Incontinence rate |

| Mucosal advancement flap | 60% | 5% |

| Draining seton | 20% | <1% |

| Fibrin glue/plug | 20% | <1% |

| Cutting seton | 95% | Up to 30% |

| Fistulotomy | 95% | Up to 30% |

| Anocutaneous flap | 60% | 5% |

| Fistulectomy | 55% | Up to 30% |

Thrombosed external haemorrhoids

Thrombosed external haemorrhoids or perianal haematomas result from a sudden increase in venous pressure or direct trauma usually from diarrhoea. Patients present with severe pain associated with a tense bluish lump (haematoma) adjacent to the anal verge. If the patient presents in the first few days, the best treatment is evacuation of the clot under local anaesthesia. If the presentation is delayed, it is often better to leave it untreated because pain would have largely subsided by then. Patients are usually left with a residual anal tag if it is untreated.

Pruritus ani

Pruritus ani results in distressing itching around the anus and results in excoriation of the skin secondary to scratching. The causes include systemic conditions, local anal pathology and psychological disturbances (Table 21.3). Certain drugs and foods can precipitate symptoms. Drugs such as colchicine and quinidine have been implicated. Foods that induce histamine release have also been implicated, including caffeine, milk, beer, tomato and lemon.

| Systemic |

Local causes should be identified and treated. If no cause is readily identifiable, the patient should be reassured and simple measures taken to alleviate the symptoms. Exacerbating foods should be avoided and a high fibre diet instigated. Simple hygiene is important with removal of any particles after bowel movements with warm water or baths (not wiping with toilet paper). Use of soap should be avoided because its slightly alkaline pH can react with the slightly acidic environment of the perianal skin. Prolonged use of topical ointments should be avoided. Loose cotton underwear may ameliorate symptoms. In severe intractable cases, subcutaneous injection of methylene blue has been used to anaesthetise the skin.

SUMMARY

Anorectal abscess results from infection in the anal glands. Symptoms include throbbing pain associated with fever or swelling.

Proctalgia fugax is a benign fleeting pain in the perineum that often wakes patients from sleep.

Bharucha AE, Wald A, Enck P, et al. Functional anorectal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1510-1518.

De Parades V, Etienney I, Bauer P, et al. Proctalgia fugax: demographic and clinical characteristics. What every doctor should know from a prospective study of 54 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:893-898.

Steele SR, Madoff RD. Systemic review: the treatment of anal fissure. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:247-257.

Rickard MJ. Anal abscesses and fistulas. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:64-72.

Zuccati G, Lotti T, Mastrolorenzo A, et al. Pruritus ani. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18:355-362.