Anaemia of chronic disease

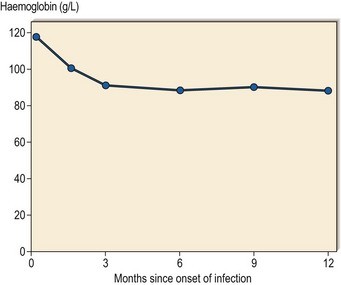

Anaemia of chronic disease (ACD) is a term used to describe a type of anaemia seen in a wide range of chronic inflammatory, infective and malignant diseases (Table 18.1). The anaemia often becomes apparent during the first few months of illness and then remains fairly constant (Fig 18.1). It is rarely severe (haemoglobin ≥90 g/L; packed cell volume (PCV) ≥0.30) but there is some correlation with the intensity of the underlying illness. For instance, in infection the anaemia is often more marked where there is a persistent fever and in malignancy where there is widespread dissemination. Patients may suffer no symptoms from their anaemia or have only slight fatigue. The importance of this type of anaemia arises not from its severity but from its ubiquity. It is widely misunderstood (for such a common disorder) and ill patients are frequently subjected to excessive haematological investigation and unnecessary treatment with haematinics. The term ACD should not be used to describe other causes of anaemia such as haemolysis or bleeding which may also complicate chronic disorders. It has been argued that the designation ACD is inappropriate but other suggested terms (e.g. anaemia of inflammation) appear even less satisfactory. The anaemia of chronic renal failure is variously referred to as ACD although it has its own specific features (see p. 96).

Fig 18.1 ACD in a patient with chronic infection.

The rate of development of anaemia and its final severity are typical of ACD.

Pathophysiology

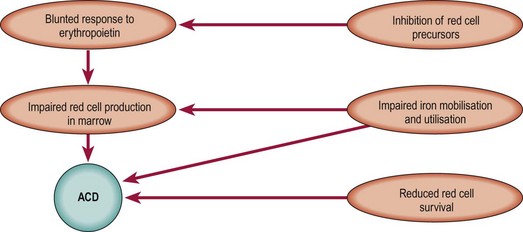

The causation of the anaemia of chronic disease has been extensively studied but questions remain. Key factors in aetiology are summarised in Figure 18.2. Inflammatory cytokines such as tissue necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-1 and -6 are implicated in all of these processes.

Fig 18.2 Overview of the aetiology of ACD.

Cytokines such as TNF, interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 and the peptide hepcidin play key roles (see text).

Diagnosis

Most patients will have a documented chronic disorder and a moderate anaemia. On occasion the anaemia is a more dominant feature and the underlying cause is not immediately apparent. The anaemia is usually of normochromic normocytic type although it can be slightly hypochromic microcytic. The blood film appearance is often unremarkable but there may be changes ‘reactive’ to the underlying disorder such as a neutrophil leucocytosis, thrombocytosis and rouleaux formation. There is a reticulocytopenia. Inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) are often raised. Serum iron concentration and transferrin concentration are usually reduced. The serum ferritin level is normal or high (as an acute phase reactant). In practice, ACD is most commonly confused with mild iron deficiency anaemia, particularly if the MCV and MCH are reduced. However, the two forms of anaemia should be distinguishable as in uncomplicated iron deficiency the transferrin concentration is elevated and the ferritin level is low. In difficult cases the serum transferrin receptor concentration and the serum transferrin receptor-ferritin index may be useful (Table 18.2). Measurement of the percentage of hypochromic red cells or reticulocyte haemoglobin content can be helpful in detecting coexistent iron-restricted red cell production in a patient with ACD. Reliable hepcidin assays are under development and are likely to enter routine clinical practice. Bone marrow examination is not routinely required but where performed will show normal or increased marrow iron stores with decreased marrow sideroblasts (Fig 18.3).

Table 18.2

Comparison of clinical and laboratory findings in ACD and iron deficiency anaemia

| Characteristic | ACD | Iron deficiency |

| Severity of anaemia | Hb usually ≥90 g/L | Very variable |

| Symptoms of anaemia | Usually mild | May be severe |

| Coexistent chronic disease | Yes | Variable |

| Red cell indices (MCV, MCH) | Normochromic | Hypochromic |

| Normocytic1 | Microcytic | |

| Blood film appearance | Often normal or reactive2 | Hypochromia |

| Microcytosis | ||

| Poikilocytosis | ||

| Target cells | ||

| Serum iron | Reduced | Reduced |

| Transferrin concentration | Reduced or normal | Increased |

| Ferritin | Normal or increased | Reduced3 |

| Serum transferrin receptor | Normal | Increased |

| Serum transferrin receptor-ferritin index4 | Low | High |

| Marrow iron stores | Normal or increased | Reduced |

1May be slightly hypochromic microcytic.

2‘Reactive’ changes in a blood film may accompany the underlying disorder; possible abnormalities include rouleaux formation, a neutrophil leucocytosis and thrombocytosis.

3Unless there is a coexistent acute phase response when the ferritin level may be normal.

4Transferrin receptor concentration divided by serum ferritin concentration (or log of plasma ferritin concentration).