Problem 43 An unwell young man in the emergency room

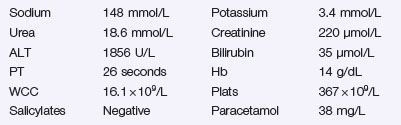

The following results become available:

Q.4

What are you going to do immediately? Describe and justify what you should look for on examination?

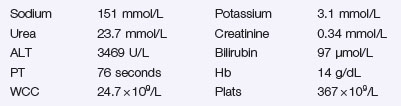

He is taken to the intensive care and intubated. Blood tests now reveal the following:

Answers

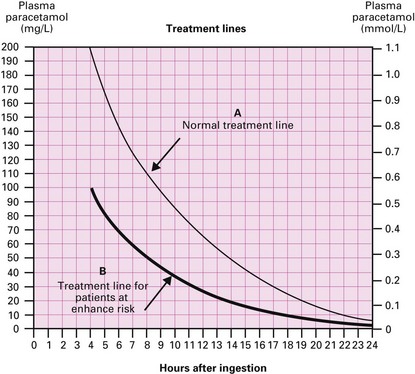

Figure 43.1 Paracetamol treatment chart.

(Courtesy of the Clinical Services Unit of the Royal Adelaide Hospital.)

All patients with deliberate self-poisoning should be assessed by psychiatric services.

A.4 This is a medical emergency.

A: Check and safeguard his airway

Call the anaesthetic team if his airway is threatened and he may need intubation.

The degree of unconsciousness should be determined by calculating and recording his Glasgow coma score (GCS), as shown in Table 43.1.

| Eye Opening | Motor Response | Verbal Response |

|---|---|---|

| 4 Spontaneous | 6 Obeys commands | 5 Orientated |

| 3 To voice | 5 Localizes to pain | 4 Confused |

| 2 To pain | 4 Withdraws from pain | 3 Inappropriate words |

| 1 None | 3 Flexion to pain | 2 Incomprehensible sounds |

| 2 Extension to pain | 1 None | |

| 1 None |

The limbs should be tested for tone, response to painful stimuli and reflexes.

The main causes of death from poisoning out of hospital include:

Note that most of these substances are not detected by the average ‘drug screen’.

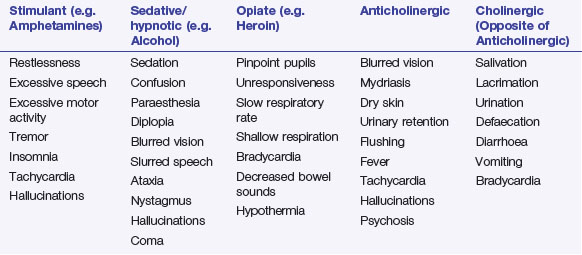

Overdoses produce various physiological effects which need to be treated, such as tachycardia, seizures or hypotension. Current teaching is to ‘treat the patient, not the poison’. Recent thinking employs the concept of ‘toxidromes’ which are groups of symptoms and signs producing a clinical picture in different overdose settings. Table 43.2 illustrates the different groups of ‘toxidromes’.

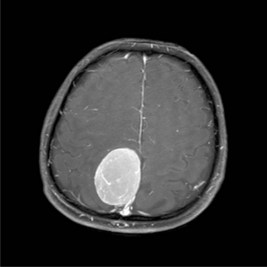

Encephalopathy (Box 43.1) due to fulminant hepatic failure is secondary to brain oedema due to cerebrovascular dilatation and rapid swelling of neurones. Early signs may include hyperreflexia, clonus, extensor posturing, teeth grinding as well as irritability. It is not uncommon for these early signs to be misinterpreted as a lack of cooperation or anxiety in such a patient.

Patients with early signs of brain oedema should be managed in ITU and intubated to reduce agitation and allow the administration of anaesthetic agents such as propofol. This patient is confused and agitated so he is moving from stage II to stage III encephalopathy (see Box 43.1). His hypoglycaemia hours earlier was a warning sign that this was to be the likely outcome. A liver transplant centre should be contacted urgently.

Revision Points

Coma

Definition

Coma is a state of deep unconsciousness where the patient does not wake up with external stimuli.

Risk Factors

Routine screening for drugs is rarely useful and is expensive.

Paracetamol Overdose (POD)

Treatment

The use of the paracetamol nomogram (see Figure 43.1) is important in determining the need for N-acetylcysteine therapy. The nomogram indicates the risk of hepatic injury associated with a paracetamol concentration at a known time after ingestion. An adequate history to establish time of ingestion is therefore very useful, but often unreliable. If in doubt, treat as the ‘worst-case scenario’.

Peak hepatotoxicity may not occur for some days. Following a significant overdose, the INR should be monitored for 24–48 hours. Patients with signs of significant hepatotoxicity should be discussed early with a liver unit. These signs include a worsening coagulopathy, rising creatinine, acidosis and the development of hepatic encephalopathy. A small proportion of patients will develop acute liver failure and some come to liver transplant (Box 43.2).