An Overview of Immunology

At the conclusion of this chapter, the reader should be able to:

• Compare an immunogen and an antigen

• Explain the functions of the immune system.

• Describe the first, second, and third lines of body defense against microbial diseases.

• Compare innate and adaptive immunity.

• Analyze a case study related to immunity.

• Correctly answer case study related multiple choice questions.

• Be prepared to participate in a discussion of critical thinking questions.

• Describe the characteristics of five mature leukocytes and their immune function.

History of Immunology

Louis Pasteur is generally considered to be the Father of Immunology. Table 1-1 lists some historic benchmarks in immunology.

Table 1-1

Significant Milestones in Immunology

| Date | Scientist(s) | Discovery |

| 1798 | Jenner | Smallpox vaccination |

| 1862 | Haeckel | Phagocytosis |

| 1880-1881 | Pasteur | Live, attenuated chicken cholera and anthrax vaccines |

| 1883-1905 | Metchnikoff | Cellular theory of immunity through phagocytosis |

| 1885 | Pasteur | Therapeutic vaccination First report of live “attenuated” vaccine for rabies |

| 1890 | Von Behring, Kitasata | Humoral theory of immunity proposed |

| 1891 | Koch | Demonstration of cutaneous (delayed-type) hypersensitivity |

| 1900 | Ehrlich | Antibody formation theory |

| 1902 | Portier, Richet | Immediate-hypersensitivity anaphylaxis |

| 1903 | Arthus | Arthus reaction of intermediate hypersensitivity |

| 1938 | Marrack | Hypothesis of antigen-antibody binding |

| 1944 | Hypothesis of allograft rejection | |

| 1949 | Salk, Sabin | Development of polio vaccine |

| 1951 | Reed | Vaccine against yellow fever |

| 1953 | Graft-versus-host reaction | |

| 1957 | Burnet | Clonal selection theory |

| 1957 | Interferon | |

| 1958-1962 | Human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) | |

| 1964-1968 | T-cell and B-cell cooperation in immune response | |

| 1972 | Identification of antibody molecule | |

| 1975 | Köhler | First monoclonal antibodies |

| 1985-1987 | Identification of genes for T cell receptor | |

| 1986 | Monoclonal hepatitis B vaccine | |

| 1986 | Mosmann | Th1 versus Th2 model of T helper cell function |

| 1996-1998 | Identification of toll-like receptors | |

| 2001 | FOXP3, the gene directing regulatory T cell development | |

| 2005 | Frazer | Development of human papillomavirus vaccine |

What is immunology?

Immunology is defined as resistance to disease, specifically infectious disease. Immunology consists of the following: the study of the molecules, cells, organs, and systems responsible for the recognition and disposal of foreign (nonself) material; how body components respond and interact; the desirable and undesirable consequences of immune interactions; and the ways in which the immune system can be advantageously manipulated to protect against or treat disease (Box 1-1). Immunologists in the Western Hemisphere generally exclude from the study of immunology the relationship among cells during embryonic development.

The immune system is composed of a large complex set of widely distributed elements, with distinctive characteristics. Specificity and memory are characteristics of lymphocytes (see Chapter 4). Various specific and nonspecific elements of the immune system demonstrate mobility, including T and B lymphocytes, immunoglobulins (antibodies), complement, and hematopoietic cells.

Function of Immunology

Nonself substances range from life-threatening infectious microorganisms to a lifesaving organ transplantation. The desirable consequences of immunity include natural resistance, recovery, and acquired resistance to infectious diseases. A deficiency or dysfunction of the immune system can cause many disorders. Undesirable consequences of immunity include allergy, rejection of a transplanted organ, or an autoimmune disorder, in which the body’s own tissues are attacked as if they were foreign. Over the last decade, a new concept, the danger theory, has challenged the classic self-nonself viewpoint; although popular, it has not been widely accepted by immunologists (see Chapter 4).

Body Defenses: Resistance to Microbial Disease

First Line of Defense

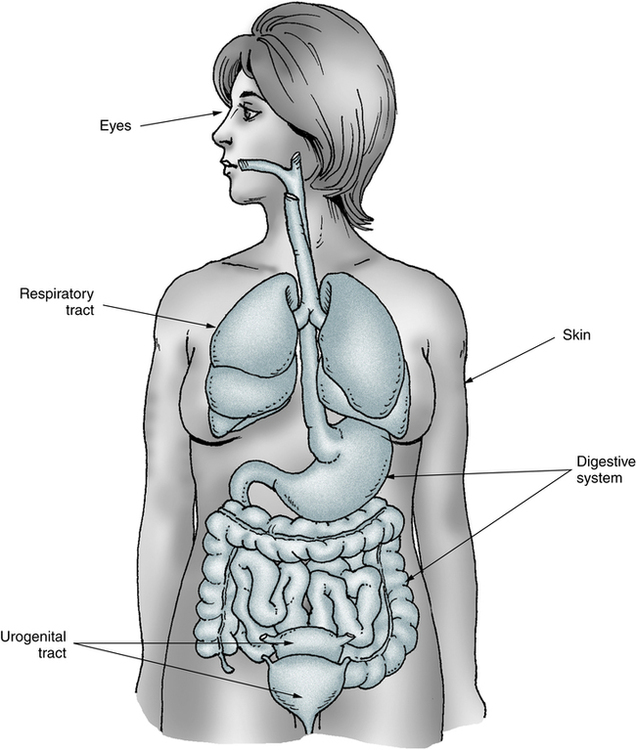

Before a pathogen can invade the human body, it must overcome the resistance provided by the body’s first line of defense (Fig. 1-1). The first barrier to infection is unbroken skin and mucosal membrane surfaces. These surfaces are essential in forming a physical barrier to many microorganisms because this is where foreign materials usually first contact the host. Keratinization of the upper layer of the skin and the constant renewal of the skin’s epithelial cells, which repairs breaks in the skin, assist in the protective function of skin and mucosal membranes. In addition, the normal flora (microorganisms normally inhabiting the skin and membranes) deter penetration or facilitate elimination of foreign microorganisms from the body.

Body fluids, specialized cells, fluids, and resident bacteria (normal biota) allow the respiratory, digestive, urogenital, integumentary, and other systems to defend the body against microbial infection.

Second Line of Defense: Natural Immunity

Natural immunity is characterized as a nonspecific mechanism. If a microorganism penetrates the skin or mucosal membranes, a second line of cellular and humoral defense mechanisms becomes operational (Box 1-2). The elements of natural resistance include phagocytic cells, complement, and the acute inflammatory reaction (see Chapter 3).

Detection of microbial pathogens is carried out by sentinel cells of the innate immune system located in tissues (macrophages and dendritic cells [DCs]) in close contact with the host’s natural environment or that are rapidly reunited to the site of infection (neutrophils). Despite their relative lack of specificity, these cellular components are essential because they are largely responsible for natural immunity to many environmental microorganisms. These phagocytic cells, which engulf invading foreign material, constitute major cellular components. Tissue damage produced by infectious or other agents results in inflammation, a series of biochemical and cellular changes that facilitate phagocytosis (engulfment and destruction) of microorganisms or damaged cells (see Chapter 3). If the degree of inflammation is sufficiently extensive, it is accompanied by an increase in the plasma concentration of acute-phase proteins or reactants, a group of glycoproteins. Acute-phase proteins are sensitive indicators of the presence of inflammatory disease and are especially useful in monitoring such conditions (see Chapter 5).

Complement proteins are the major humoral (fluid) component of natural immunity (see Chapter 5). Other substances of the humoral component include lysozymes and interferon, sometimes described as natural antibiotics. Interferon is a family of proteins produced rapidly by many cells in response to viral infection; it blocks the replication of virus in other cells.

Third Line of Defense: Adaptive Immunity

Adaptive immunity, as with natural immunity, is composed of cellular and humoral components (Box 1-3). The major cellular component of acquired immunity is the lymphocyte (see Chapter 4); the major humoral component is the antibody (see Chapter 2). Lymphocytes selectively respond to nonself materials (antigens), which leads to immune memory and a permanently altered pattern of response or adaptation to the environment. Most actions in the two categories of the adaptive response, humoral-mediated immunity and cell-mediated immunity, are exerted by the interaction of antibody with complement and the phagocytic cells (natural immunity) and of T cells with macrophages (Table 1-2).

Table 1-2

Characteristics of Two Types of Adaptive Immunity

| Humoral-Mediated Immunity | Cell-Mediated Immunity | |

| Mechanism | Antibody mediated | Cell mediated |

| Cell type | B lymphocytes | T lymphocytes |

| Mode of action | Antibodies in serum | Direct cell-to-cell contact or soluble products secreted by cells |

| Purpose | Primary defense against bacterial infection | Defense against viral and fungal infections, intracellular organisms, tumor antigens, and graft rejection |

Humoral-Mediated Immunity

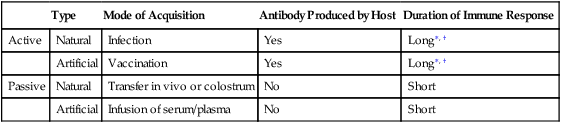

If specific antibodies have been formed to antigenic stimulation, they are available to protect the body against foreign substances. The recognition of foreign substances and subsequent production of antibodies to these substances define immunity. Antibody-mediated immunity to infection can be acquired if the antibodies are formed by the host or if they are received from another source; these two types of acquired immunity are called active immunity and passive immunity, respectively (Table 1-3).

Table 1-3

Comparison of Types of Acquired Immunity

| Type | Mode of Acquisition | Antibody Produced by Host | Duration of Immune Response | |

| Active | Natural | Infection | Yes | Long∗, † |

| Artificial | Vaccination | Yes | Long∗, † | |

| Passive | Natural | Transfer in vivo or colostrum | No | Short |

| Artificial | Infusion of serum/plasma | No | Short |

†IgG immune antibody half-life is 23 days. Memory cells (memory lymphocytes) lifespan is years.

Active immunity can be acquired by natural exposure in response to an infection or natural series of infections, or through intentional injection of an antigen. The latter, vaccination (see Chapter 16), is an effective method of stimulating antibody production and memory (acquired resistance) without contracting the disease. Suspensions of antigenic materials used for immunization may be of animal or plant origin. These products may consist of living suspensions of weak or attenuated cells or viruses, killed cells or viruses, or extracted bacterial products (e.g., altered and no longer poisonous toxoids used to immunize against diphtheria and tetanus). The selected agents should stimulate the production of antibodies without clinical signs and symptoms of disease in an immunocompetent host (host is able to recognize a foreign antigen and build specific antigen-directed antibodies) and result in permanent antigenic memory. Booster vaccinations may be needed in some cases to expand the pool of memory cells. The mechanisms of antigen recognition and antibody production are discussed in Chapter 2.

Artificial passive immunity is achieved by the infusion of serum or plasma containing high concentrations of antibody or lymphocytes from an actively immunized individual. Passive immunity via pre-formed antibodies in serum provides immediate, temporary antibody protection against microorganisms (e.g., hepatitis A) by administering preformed antibodies. The recipient will benefit only temporarily from passive immunity for as long as the antibodies persist in the circulation. Immune antibodies are usually of the IgG type (see Chapter 2, Antigens and Antibodies) with a half-life of 23 days.∗

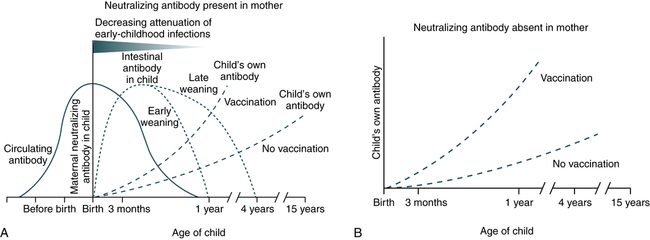

In addition, passive immunity can be acquired naturally by the fetus through the transfer of antibodies by the maternal placental circulation in utero during the last 3 months of pregnancy (Fig. 1-2). Maternal antibodies are also transferred to the newborn after birth. The amount and specificity of maternal antibodies depend on the mother’s immune status to infectious diseases that she has experienced.

A, Maternal neutralizing antibodies cross the placenta to protect the offspring and attenuate systemic infections for 6 to 12 months after birth. The timing of weaning, early or late, influences the levels of intestinal antibodies derived from breast milk and the rate of attenuation of gastrointestinal infection. B, The absence of specific neutralizing antibodies in maternal serum leads to the absence of a protective effect. (From Zinkernagel RM: Maternal antibodies, childhood infections, and autoimmune diseases, N Engl J Med 345:1331–1335, 2001.)

Cell-Mediated Immunity

Cell-mediated immunity is moderated by the link between T lymphocytes and phagocytic cells (i.e., monocytes-macrophages). A B lymphocyte can probably respond to a native antigenic determinant of the appropriate fit. A T lymphocyte responds to antigens presented by other cells in the context of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins (see Chapter 31). The T lymphocyte does not directly recognize the antigens of microorganisms or other living cells, such as allografts (tissue from a genetically different member of the same species, such as a human kidney), but recognizes when the antigen is present on the surface of an antigen-presenting cell (APC), the macrophage. APCs were at first thought to be limited to cells of the mononuclear phagocyte system. Recently, other types of cells (e.g., endothelial, glial) have been shown to possess the ability to present antigens.

Lymphocytes are immunologically active through various types of direct cell-to-cell contact and by the production of soluble factors (see Chapter 5). Nonspecific soluble factors are made by or act on various elements of the immune system. These molecules are collectively called cytokines. Some mediators that act between leukocytes are called interleukins.

Comparison of Innate and Adaptive Immunity

Traditionally, the immune system has been divided into innate and adaptive components, each with a different function and role. The innate immune system, an ancient form of host defense, appeared before the adaptive immune system. Mechanisms of innate immunity (e.g., phagocytes) and the alternative complement pathways are activated immediately after infection and quickly begin to control multiplication of infecting microorganisms. By comparison, the adaptive immune system (Table 1-4) is organized around two classes of cells, T and B lymphocytes. When an individual lymphocyte encounters an antigen that binds to its unique antigen receptor site, activation and proliferation of that lymphocyte occur. This is called clonal selection and is responsible for the basic properties of the adaptive immune system.

Table 1-4

Comparison of Innate and Adaptive Immunity

| Innate Immunity | Adaptive Immunity |

| Pathogen recognized by receptors encoded in the germline | Pathogen recognized by receptors generated randomly |

| Receptors have broad specificity, i.e., recognize many related molecular structures (PAMPs) | Receptors have very narrow specificity; i.e., recognize a specific epitope |

| Immediate response | Slow (3-5 days) response |

| Little or no memory of prior antigenic exposure | Memory of prior antigenic exposure |

Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns and Pattern Recognition Receptors

Pattern Recognition Receptors

1. Secreted PRRs are molecules that circulate in blood and lymph; circulating proteins bind to PAMPs on the surface of many pathogens. This interaction triggers the complement cascade, leading to the opsonization of the pathogen and its speedy phagocytosis (discussed in Chapter 3).

2. Phagocytosis receptors are cell surface receptors that bind the pathogen, initiating a signal leading to the release of effector molecules (e.g., cytokines). Macrophages have cell surface receptors that recognize PAMPs containing mannose.

3. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a set of transmembrane receptors that recognize different types of PAMPs. TLRs are found on macrophages, dendritic cells, and epithelial cells.

• Mammals have multiple TLRs, with each exhibiting a specialized function, frequently with the aid of accessory molecules, in a subset of PAMPs. In this way, TLRs identify the nature of the pathogen and turn on an effector response appropriate for counteracting with it. These signaling cascades lead to the expression of various cytokine genes. Examples include TLR-1, which binds to the peptidoglycan of gram-positive bacteria and TLR-2, which binds lipoproteins of gram-negative bacteria.

In all these cases, binding of the pathogen to the TLR initiates a signaling pathway, leading to the activation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB, light-chain enhancer of activated B cells). This transcription factor turns on many cytokine genes, such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin-1 (IL-1), and chemokines. All these effector molecules lead to the inflammation site (see Chapter 5).

Chapter Highlights

• Immunology is defined as the study of the molecules, cells, organs, and systems responsible for the recognition and disposal of nonself material; how body components respond and interact; desirable or undesirable consequences of immune interactions; and how the immune system can be manipulated to protect against or treat disease.

• The function of the immune system is to recognize self from nonself and to defend the body against nonself.

• The first line of defense against infection is unbroken skin, mucosal membrane surfaces, and secretions.

• Natural immunity consisting of cellular and humoral defense mechanisms forms the second line of body defenses.

• If a microorganism overwhelms the body’s natural resistance, a third line of defensive resistance, acquired (or adaptive) immunity, allows the body to recognize, remember, and respond to a specific stimulus, an antigen. Antibody-mediated immunity to infection can be acquired if the antibodies are formed by the host (active immunity) or received from another source (passive immunity).

• Cell-mediated immunity differs from antibody-mediated immunity.

• Lymphocytes are immunologically active through direct cell to cell contact and production of cytokines for specific immunologic functions, such as recruitment of phagocytic cells to the site of inflammation.

• The main difference between the innate and adaptive immune systems is the mechanisms and receptors used for immune recognition.