Chapter 17 Amputations of the Hip and Pelvis

Disarticulation of the Hip

Anatomical Hip Disarticulation

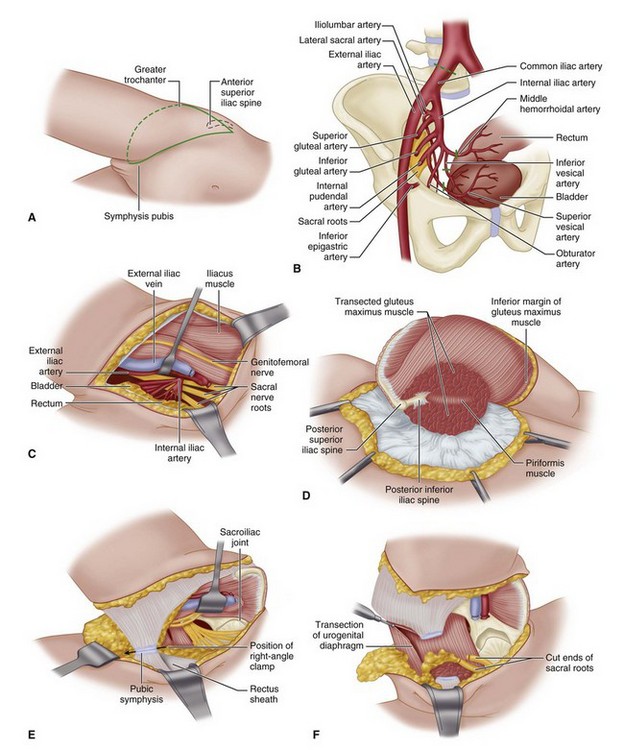

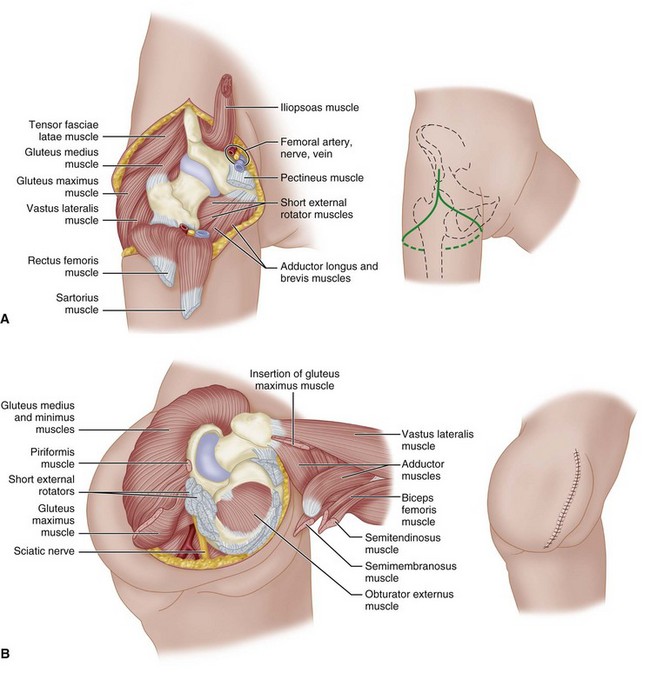

With the patient in the lateral decubitus position, make an anterior racquet-shaped incision (Fig. 17-1A), beginning the incision at the anterior superior iliac spine and curving it distally and medially almost parallel with the inguinal ligament to a point on the medial aspect of the thigh 5 cm distal to the origin of the adductor muscles. Isolate and ligate the femoral artery and vein, and divide the femoral nerve; continue the incision around the posterior aspect of the thigh about 5 cm distal to the ischial tuberosity and along the lateral aspect of the thigh about 8 cm distal to the base of the greater trochanter. From this point, curve the incision proximally to join the beginning of the incision just inferior to the anterior superior iliac spine.

With the patient in the lateral decubitus position, make an anterior racquet-shaped incision (Fig. 17-1A), beginning the incision at the anterior superior iliac spine and curving it distally and medially almost parallel with the inguinal ligament to a point on the medial aspect of the thigh 5 cm distal to the origin of the adductor muscles. Isolate and ligate the femoral artery and vein, and divide the femoral nerve; continue the incision around the posterior aspect of the thigh about 5 cm distal to the ischial tuberosity and along the lateral aspect of the thigh about 8 cm distal to the base of the greater trochanter. From this point, curve the incision proximally to join the beginning of the incision just inferior to the anterior superior iliac spine.

Detach the sartorius muscle from the anterior superior iliac spine and the rectus femoris from the anterior inferior iliac spine, and reflect them both distally.

Detach the sartorius muscle from the anterior superior iliac spine and the rectus femoris from the anterior inferior iliac spine, and reflect them both distally.

Divide the pectineus about 0.6 cm from the pubis.

Divide the pectineus about 0.6 cm from the pubis.

Rotate the thigh externally to bring the lesser trochanter and the iliopsoas tendon into view; divide the latter at its insertion and reflect it proximally.

Rotate the thigh externally to bring the lesser trochanter and the iliopsoas tendon into view; divide the latter at its insertion and reflect it proximally.

Detach the adductor and gracilis muscles from the pubis, and divide at its origin that part of the adductor magnus that arises from the ischium.

Detach the adductor and gracilis muscles from the pubis, and divide at its origin that part of the adductor magnus that arises from the ischium.

Develop the muscle plane between the pectineus and obturator externus and short external rotators of the hip to expose the branches of the obturator artery. Clamp, ligate, and divide the branches at this point. Later in the operation the obturator externus muscle is divided at its insertion on the femur instead of at its origin on the pelvis because otherwise the obturator artery may be severed and might retract into the pelvis, leading to hemorrhage that could be difficult to control.

Develop the muscle plane between the pectineus and obturator externus and short external rotators of the hip to expose the branches of the obturator artery. Clamp, ligate, and divide the branches at this point. Later in the operation the obturator externus muscle is divided at its insertion on the femur instead of at its origin on the pelvis because otherwise the obturator artery may be severed and might retract into the pelvis, leading to hemorrhage that could be difficult to control.

Rotate the thigh internally, and detach the gluteus medius and minimus muscles from their insertions on the greater trochanter and retract them proximally.

Rotate the thigh internally, and detach the gluteus medius and minimus muscles from their insertions on the greater trochanter and retract them proximally.

Divide the fascia lata and the most distal fibers of the gluteus maximus muscle distal to the insertion of the tensor fasciae latae muscle in the line of the skin incision, and separate the tendon of the gluteus maximus from its insertion on the linea aspera. Reflect this muscle mass proximally.

Divide the fascia lata and the most distal fibers of the gluteus maximus muscle distal to the insertion of the tensor fasciae latae muscle in the line of the skin incision, and separate the tendon of the gluteus maximus from its insertion on the linea aspera. Reflect this muscle mass proximally.

Identify, ligate, and divide the sciatic nerve.

Identify, ligate, and divide the sciatic nerve.

Divide the short external rotators of the hip (i.e., the piriformis, gemelli, obturator internus, obturator externus, and quadratus femoris) at their insertions on the femur, and sever the hamstring muscles from the ischial tuberosity.

Divide the short external rotators of the hip (i.e., the piriformis, gemelli, obturator internus, obturator externus, and quadratus femoris) at their insertions on the femur, and sever the hamstring muscles from the ischial tuberosity.

Incise the hip joint capsule and the ligamentum teres to complete the disarticulation (Fig. 17-1B).

Incise the hip joint capsule and the ligamentum teres to complete the disarticulation (Fig. 17-1B).

Bring the gluteal flap anteriorly, and suture the distal part of the gluteal muscles to the origin of the pectineus and adductor muscles.

Bring the gluteal flap anteriorly, and suture the distal part of the gluteal muscles to the origin of the pectineus and adductor muscles.

Place a drain in the inferior part of the incision, and approximate the skin edges with interrupted nonabsorbable sutures.

Place a drain in the inferior part of the incision, and approximate the skin edges with interrupted nonabsorbable sutures.

FIGURE 17-1 Boyd disarticulation of hip. A, Femoral vessels and nerve have been ligated, and sartorius, rectus femoris, pectineus, and iliopsoas muscles have been detached. Inset, Line of skin incision. B, Gluteal muscles have been separated from insertions, sciatic nerve and short external rotators have been divided, and hamstring muscles have been detached from ischial tuberosity. Inset, Final closure of stump. SEE TECHNIQUE 17-1.

(Redrawn from Boyd HB: Anatomic disarticulation of the hip, Surg Gynecol Obstet 84:346, 1947.)

Posterior Flap

Begin the incision at the level of the inguinal ligament, carry it distally over the femoral artery for 10 cm, curve it along the medial aspect of the thigh, continue it laterally and proximally over the greater trochanter, and swing it anteriorly to the starting point. A posteromedial flap long enough to cover the end of the stump is formed.

Begin the incision at the level of the inguinal ligament, carry it distally over the femoral artery for 10 cm, curve it along the medial aspect of the thigh, continue it laterally and proximally over the greater trochanter, and swing it anteriorly to the starting point. A posteromedial flap long enough to cover the end of the stump is formed.

Isolate, ligate, and divide the femoral vessels, and section the femoral nerve to fall well proximal to the inguinal ligament.

Isolate, ligate, and divide the femoral vessels, and section the femoral nerve to fall well proximal to the inguinal ligament.

Abduct the thigh widely, and divide the adductor muscles at their pubic origins.

Abduct the thigh widely, and divide the adductor muscles at their pubic origins.

Section the two branches of the obturator nerve so that they retract away from pressure areas.

Section the two branches of the obturator nerve so that they retract away from pressure areas.

Free the origins of the sartorius and rectus femoris from the anterior superior and anterior inferior iliac spines. Moderately adduct and internally rotate the thigh, and divide the tensor fasciae latae at the level of the proximal end of the greater trochanter; at the same level, divide close to bone the muscles attached to the trochanter. Next, abduct the thigh markedly and divide the gluteus maximus at the distal end of the posterior skin flap.

Free the origins of the sartorius and rectus femoris from the anterior superior and anterior inferior iliac spines. Moderately adduct and internally rotate the thigh, and divide the tensor fasciae latae at the level of the proximal end of the greater trochanter; at the same level, divide close to bone the muscles attached to the trochanter. Next, abduct the thigh markedly and divide the gluteus maximus at the distal end of the posterior skin flap.

Identify, ligate, and divide the sciatic nerve.

Identify, ligate, and divide the sciatic nerve.

Divide the joint capsule, and complete the disarticulation.

Divide the joint capsule, and complete the disarticulation.

Swing the long posteromedial flap containing the gluteus maximus anteriorly, and suture it to the anterior margins of the incision.

Swing the long posteromedial flap containing the gluteus maximus anteriorly, and suture it to the anterior margins of the incision.

Hemipelvectomy

The standard hemipelvectomy employs a posterior or gluteal flap and disarticulates the symphysis pubis and sacroiliac joint and the ipsilateral limb. An extended hemipelvectomy includes resection of adjacent musculoskeletal structures, such as the sacrum or parts of the lumbar spine. In a conservative hemipelvectomy, the bony section divides the ilium above the acetabulum, preserving the crest of the ilium. Internal hemipelvectomy is a limb-sparing resection, often achieving proximal and medial margins equal to the corresponding amputation. This procedure is discussed in Chapter 24.

Standard Hemipelvectomy

Insert a Foley catheter. Place the patient in a lateral decubitus position with the involved side up. Support the patient so that the table can be tilted to facilitate anterior and posterior dissection.

Insert a Foley catheter. Place the patient in a lateral decubitus position with the involved side up. Support the patient so that the table can be tilted to facilitate anterior and posterior dissection.

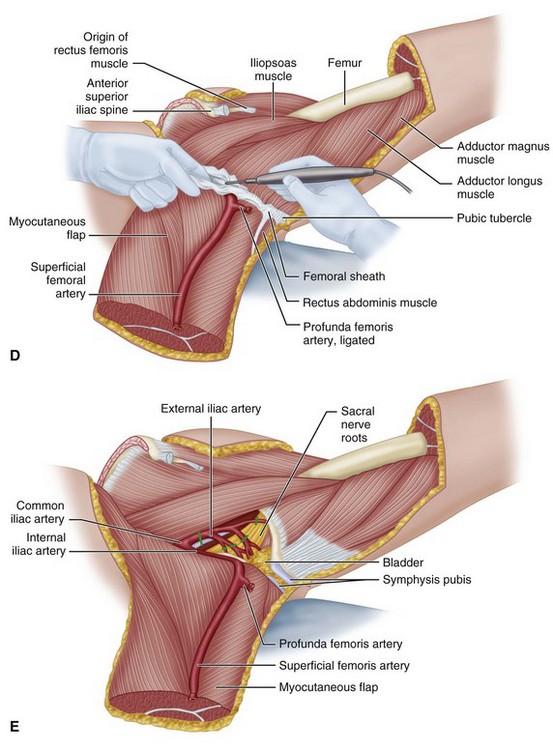

Perform the anterior dissection first, making an incision extending from 5 cm above the anterior superior iliac spine to the pubic tubercle (Fig. 17-2A). Deepen the incision through the tensor fascia, external oblique aponeurosis, and internal oblique and transversalis muscles.

Perform the anterior dissection first, making an incision extending from 5 cm above the anterior superior iliac spine to the pubic tubercle (Fig. 17-2A). Deepen the incision through the tensor fascia, external oblique aponeurosis, and internal oblique and transversalis muscles.

Retract the spermatic cord medially.

Retract the spermatic cord medially.

Expose the iliac fossa by blunt dissection.

Expose the iliac fossa by blunt dissection.

Elevate the parietal peritoneum off the iliac vessels, and permit it to fall inferiorly with the viscera.

Elevate the parietal peritoneum off the iliac vessels, and permit it to fall inferiorly with the viscera.

Ligate the inferior epigastric vessels.

Ligate the inferior epigastric vessels.

Release the rectus muscle and sheath from the pubis.

Release the rectus muscle and sheath from the pubis.

Identify the iliac vessels, retract the ureter medially, and ligate and divide the common iliac artery and vein. Put lateral traction on the iliac artery and vein, and ligate and divide their branches to the sacrum, rectum, and bladder, separating the rectum and bladder from the pelvic side wall and exposing the sacral nerve roots (Fig. 17-2B and C). If necessary for exposure, divide the symphysis pubis and sacroiliac joint before this dissection.

Identify the iliac vessels, retract the ureter medially, and ligate and divide the common iliac artery and vein. Put lateral traction on the iliac artery and vein, and ligate and divide their branches to the sacrum, rectum, and bladder, separating the rectum and bladder from the pelvic side wall and exposing the sacral nerve roots (Fig. 17-2B and C). If necessary for exposure, divide the symphysis pubis and sacroiliac joint before this dissection.

Pack the anterior wound with warm, moist gauze packs.

Pack the anterior wound with warm, moist gauze packs.

Make a posterior skin incision, extending from 5 cm above the anterior superior iliac spine, coursing over the anterior aspect of the greater trochanter, paralleling the gluteal crease posteriorly around the thigh, and connecting with the inferior end of the anterior incision (see Fig. 17-2A).

Make a posterior skin incision, extending from 5 cm above the anterior superior iliac spine, coursing over the anterior aspect of the greater trochanter, paralleling the gluteal crease posteriorly around the thigh, and connecting with the inferior end of the anterior incision (see Fig. 17-2A).

Raise the posterior flap by dissecting the gluteal fascia directly off the gluteus maximus. Include the fascia with the flap. If possible, include the medial portion of the gluteus maximus with the flap. Superiorly elevate the flap off the iliac crest.

Raise the posterior flap by dissecting the gluteal fascia directly off the gluteus maximus. Include the fascia with the flap. If possible, include the medial portion of the gluteus maximus with the flap. Superiorly elevate the flap off the iliac crest.

Divide the external oblique, sacrospinalis, latissimus dorsi, and quadratus lumborum from the crest of the ilium.

Divide the external oblique, sacrospinalis, latissimus dorsi, and quadratus lumborum from the crest of the ilium.

Reflect the gluteus maximus from the sacrotuberous ligament, coccyx, and sacrum (Fig. 17-2D).

Reflect the gluteus maximus from the sacrotuberous ligament, coccyx, and sacrum (Fig. 17-2D).

Divide the iliopsoas muscle; genitofemoral, obturator, and femoral nerves; and lumbosacral nerve trunk at the level of the iliac crest.

Divide the iliopsoas muscle; genitofemoral, obturator, and femoral nerves; and lumbosacral nerve trunk at the level of the iliac crest.

Abduct the hip, placing tension on the soft tissues around the symphysis pubis. Pass a long right-angle clamp around the symphysis, and divide it with a scalpel (Fig. 17-2E).

Abduct the hip, placing tension on the soft tissues around the symphysis pubis. Pass a long right-angle clamp around the symphysis, and divide it with a scalpel (Fig. 17-2E).

Divide the sacral nerve roots, preserving the nervi erigentes if possible. Reflect the iliacus muscle laterally, exposing the anterior aspect of the sacroiliac joint.

Divide the sacral nerve roots, preserving the nervi erigentes if possible. Reflect the iliacus muscle laterally, exposing the anterior aspect of the sacroiliac joint.

Divide the joint anteriorly with a scalpel or osteotome, and divide the iliolumbar ligament.

Divide the joint anteriorly with a scalpel or osteotome, and divide the iliolumbar ligament.

Place considerable traction on the extremity, separating the pelvic side wall from the viscera. Proceeding from anterior to posterior, divide the following from the pelvic side wall: urogenital diaphragm, pubococcygeus, ischiococcygeus, iliococcygeus, piriformis, sacrotuberous ligament, and sacrospinous ligaments (Fig. 17-2F). All of these structures must be divided under tension. Move the extremity anteriorly, and divide the posterior aspect of the sacroiliac joint to complete the dissection.

Place considerable traction on the extremity, separating the pelvic side wall from the viscera. Proceeding from anterior to posterior, divide the following from the pelvic side wall: urogenital diaphragm, pubococcygeus, ischiococcygeus, iliococcygeus, piriformis, sacrotuberous ligament, and sacrospinous ligaments (Fig. 17-2F). All of these structures must be divided under tension. Move the extremity anteriorly, and divide the posterior aspect of the sacroiliac joint to complete the dissection.

Place suction drains in the wound, and suture the gluteal fascia to the fascia of the abdominal wall. Close the skin.

Place suction drains in the wound, and suture the gluteal fascia to the fascia of the abdominal wall. Close the skin.

Anterior Flap Hemipelvectomy

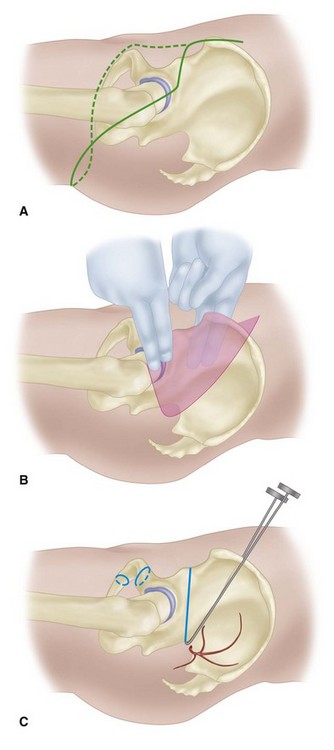

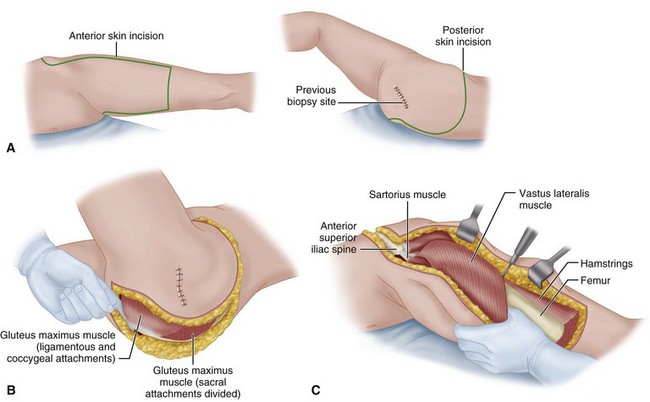

Insert a Foley catheter. Place the patient in the lateral decubitus position with the operated side up, and secure the patient to the table so that it can be tilted to facilitate the anterior and posterior dissections. Prepare the skin from toes to rib cages, and drape the extremity free. Mark out the skin incision such that the length and width of the anterior flap adequately covers the posterior defect that is to be created (Fig. 17-3A).

Insert a Foley catheter. Place the patient in the lateral decubitus position with the operated side up, and secure the patient to the table so that it can be tilted to facilitate the anterior and posterior dissections. Prepare the skin from toes to rib cages, and drape the extremity free. Mark out the skin incision such that the length and width of the anterior flap adequately covers the posterior defect that is to be created (Fig. 17-3A).

Make an incision superiorly across the iliac crest to the midlateral point, around the buttock just lateral to the anus, and to the midmedial point of the thigh. Carry the incision down the thigh a distance adequate to cover the posterior defect, across the front of the thigh to the midlateral point, and superiorly to join the superior incision.

Make an incision superiorly across the iliac crest to the midlateral point, around the buttock just lateral to the anus, and to the midmedial point of the thigh. Carry the incision down the thigh a distance adequate to cover the posterior defect, across the front of the thigh to the midlateral point, and superiorly to join the superior incision.

Perform the posterior dissection first. Preserve a skin margin of 3 cm from the anus. Detach the gluteus maximus and sacrospinalis from the sacrum. Detach the external oblique, sacrospinalis, latissimus dorsi, and quadratus lumborum muscles from the iliac crest.

Perform the posterior dissection first. Preserve a skin margin of 3 cm from the anus. Detach the gluteus maximus and sacrospinalis from the sacrum. Detach the external oblique, sacrospinalis, latissimus dorsi, and quadratus lumborum muscles from the iliac crest.

Flex the hip, and place the tissues in the region of the gluteal crease under tension. Detach the remaining origins of the gluteus maximus from the coccyx and sacrotuberous ligament (Fig. 17-3B). Bluntly dissect lateral to the rectum into the ischiorectal fossa.

Flex the hip, and place the tissues in the region of the gluteal crease under tension. Detach the remaining origins of the gluteus maximus from the coccyx and sacrotuberous ligament (Fig. 17-3B). Bluntly dissect lateral to the rectum into the ischiorectal fossa.

Move to the front of the patient, and deepen the anterior incision at the junction of the middle and distal thirds of the thigh through the quadriceps to the femur. Continue the dissection laterally from this point in a cephalad direction to the anterior superior spine severing the vastus lateralis from the femur and separating the tensor fascia femoris from its fascia such that it is included with the specimen (Fig. 17-3C).

Move to the front of the patient, and deepen the anterior incision at the junction of the middle and distal thirds of the thigh through the quadriceps to the femur. Continue the dissection laterally from this point in a cephalad direction to the anterior superior spine severing the vastus lateralis from the femur and separating the tensor fascia femoris from its fascia such that it is included with the specimen (Fig. 17-3C).

Start the medial dissection at Hunter’s canal, and ligate and divide the superficial femoral vessels. Trace the vessels superiorly to the inguinal ligament, dividing and ligating multiple small branches to the adductor muscles.

Start the medial dissection at Hunter’s canal, and ligate and divide the superficial femoral vessels. Trace the vessels superiorly to the inguinal ligament, dividing and ligating multiple small branches to the adductor muscles.

Place upward traction on the myocutaneous flap, and detach the vastus medialis and intermedius from the femur.

Place upward traction on the myocutaneous flap, and detach the vastus medialis and intermedius from the femur.

Ligate and divide the profunda femoris vessels at their origin from the common femoral artery and vein.

Ligate and divide the profunda femoris vessels at their origin from the common femoral artery and vein.

Separate the myocutaneous flap from the pelvis by releasing the abdominal muscles from the iliac crest, the sartorius from the anterior superior spine, the rectus femoris from the anterior inferior spine, and the rectus abdominis from the pubis (Fig. 17-3D).

Separate the myocutaneous flap from the pelvis by releasing the abdominal muscles from the iliac crest, the sartorius from the anterior superior spine, the rectus femoris from the anterior inferior spine, and the rectus abdominis from the pubis (Fig. 17-3D).

Retract the flap medially, and dissect along the femoral nerve into the pelvis to expose the iliac vessels.

Retract the flap medially, and dissect along the femoral nerve into the pelvis to expose the iliac vessels.

Divide the symphysis pubis while protecting the bladder and urethra.

Divide the symphysis pubis while protecting the bladder and urethra.

Ligate and divide the internal iliac vessels at their origin from the common iliacs. While placing medial traction on the bladder and rectus, divide the visceral branches of the internal iliac vessels. Divide the psoas muscle as it joins the iliacus, and divide the underlying obturator nerve, but protect the femoral nerve going into the flap. Divide the lumbosacral nerve and the sacral nerve roots (Fig. 17-3E).

Ligate and divide the internal iliac vessels at their origin from the common iliacs. While placing medial traction on the bladder and rectus, divide the visceral branches of the internal iliac vessels. Divide the psoas muscle as it joins the iliacus, and divide the underlying obturator nerve, but protect the femoral nerve going into the flap. Divide the lumbosacral nerve and the sacral nerve roots (Fig. 17-3E).

Put traction on the pelvic diaphragm by elevating the extremity, and divide the urogenital diaphragm, levator ani, and piriformis near the pelvis.

Put traction on the pelvic diaphragm by elevating the extremity, and divide the urogenital diaphragm, levator ani, and piriformis near the pelvis.

Divide the sacroiliac joint and the iliolumbar ligament, and remove the specimen.

Divide the sacroiliac joint and the iliolumbar ligament, and remove the specimen.

Turn the quadriceps flap onto the posterior defect, and close the wound over suction drains by suturing the quadriceps to the abdominal wall, sacrospinalis, sacrum, and pelvic diaphragm.

Turn the quadriceps flap onto the posterior defect, and close the wound over suction drains by suturing the quadriceps to the abdominal wall, sacrospinalis, sacrum, and pelvic diaphragm.

FIGURE 17-3 Anterior flap hemipelvectomy. A, Anterior and posterior incision. B, Detachment of gluteus maximus origins from coccyx and sacrotuberous ligament. C, Severing vastus lateralis from femur and separating tensor fascia femoris from fascia. D, Separation of myocutaneous flap. E, Transection of internal iliac vessels and branches. SEE TECHNIQUE 17-4.

Conservative Hemipelvectomy

Insert a Foley catheter. Place the patient in a lateral decubitus position with the operated side up, and secure the patient to the table so that it can be tilted to either side.

Insert a Foley catheter. Place the patient in a lateral decubitus position with the operated side up, and secure the patient to the table so that it can be tilted to either side.

Start the incision 1 to 2 cm above the anterior superior iliac spine, and continue it posteriorly and laterally across the greater trochanter to the gluteal crease. Follow the crease to the medial thigh posteriorly. Begin a second incision from the first incision 5 cm below its starting point, and continue it to just above and parallel to the inguinal ligament to the pubic tubercle. Carry the incision posteriorly across the medial thigh to join the first incision (Fig. 17-4A).

Start the incision 1 to 2 cm above the anterior superior iliac spine, and continue it posteriorly and laterally across the greater trochanter to the gluteal crease. Follow the crease to the medial thigh posteriorly. Begin a second incision from the first incision 5 cm below its starting point, and continue it to just above and parallel to the inguinal ligament to the pubic tubercle. Carry the incision posteriorly across the medial thigh to join the first incision (Fig. 17-4A).

Perform the anterior dissection first. Divide the abdominal wall muscles, exposing the peritoneum.

Perform the anterior dissection first. Divide the abdominal wall muscles, exposing the peritoneum.

Bluntly dissect the retroperitoneal space exposing the iliac vessels (Fig. 17-4B). Ligate and divide the external iliac vessels just distal to the internal iliacs.

Bluntly dissect the retroperitoneal space exposing the iliac vessels (Fig. 17-4B). Ligate and divide the external iliac vessels just distal to the internal iliacs.

Divide the symphysis pubis, protecting the bladder and urethra.

Divide the symphysis pubis, protecting the bladder and urethra.

Divide the ilium through the greater sciatic notch as follows: bluntly dissect the iliopsoas muscle from the medial wall of the ilium by passing a finger from the anterior superior spine to the greater sciatic notch. Similarly dissect the gluteal muscles from the lateral aspect of the ilium. Pass a Gigli saw through the greater sciatic notch below the origin of the gluteus minimus, and divide the ilium (Fig. 17-4C).

Divide the ilium through the greater sciatic notch as follows: bluntly dissect the iliopsoas muscle from the medial wall of the ilium by passing a finger from the anterior superior spine to the greater sciatic notch. Similarly dissect the gluteal muscles from the lateral aspect of the ilium. Pass a Gigli saw through the greater sciatic notch below the origin of the gluteus minimus, and divide the ilium (Fig. 17-4C).

Now the extremity can be positioned to place the various muscle groups under tension so that they can be divided at appropriate levels along with the femoral, obturator, and sciatic nerves. Care should be taken to divide the urogenital and pelvic diaphragms at their pelvic attachments, protecting the bladder and rectum.

Now the extremity can be positioned to place the various muscle groups under tension so that they can be divided at appropriate levels along with the femoral, obturator, and sciatic nerves. Care should be taken to divide the urogenital and pelvic diaphragms at their pelvic attachments, protecting the bladder and rectum.

Baliski CR, Schachar NS, McKinnon G, et al. Hemipelvectomy: a changing perspective for a rare procedure. Can J Surg. 2004;47:99.

Chan JWH, Virgo KS, Johnson FE. Hemipelvectomy for severe decubitus ulcers in patients with previous spinal cord injury. Am J Surg. 2003;185:69.

Chansky HA, Hip disarticulation and transpelvic amputation: surgical management. Smith, DG, Michael, JW, Bowker, JH. Atlas of amputations and limb deficiencies: surgical, prosthetic, and rehabilitation principles, ed 3, Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2004.

Chin T, Oyabu H, Maeda Y, et al. Energy consumption during prosthetic walking and wheelchair locomotion by elderly hip disarticulation amputees. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;88:399.

Johnson ON, III., Potter BK, Bonnecarrere ER. Modified abdominoplasty advancement flap for coverage of trauma-related hip disarticulations complicated by heterotopic ossification: a report of two cases and description of a surgical technique. J Trauma. 2008;64:E54.

Krijnen MR, Wuisman PI. Emergency hemipelvectomy as a result of uncontrolled infection after total hip arthroplasty: two case reports. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:803.

Senchenkov A, Moran SL, Petty PM, et al. Predictors of complications and outcomes of external hemipelvectomy wounds: account of 160 consecutive cases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:355.

Yari P, Dijkstra PU, Geertzen JHB. Functional outcome of hip disarticulation and hemipelvectomy: a cross-sectional national description study in the Netherlands. Clin Rehabil. 2008;22:1127.

Zalavras CG, Rigopoulos N, Ahlmann E, Patzakis MJ. Hip disarticulation for severe lower extremity infections. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:1721.

Bailey RW, Stevens DB. Radical exarticulation of the extremities for the curative and palliative treatment of malignant neoplasms. J Bone Joint Surg. 1961;43A:845.

Brittain HA. Hindquarter amputation. J Bone Joint Surg. 1949;31B:104.

Burgess EM, Romano RL, Zettl JH. The management of lower extremity amputations, TR 10-6. Washington, DC: Veterans Administration; 1969.

Burgess EM, Traub JE, Wilson AB, Jr. Immediate postsurgical prosthetics in the management of lower extremity amputees, TR 10-5. Washington, DC: Veterans Administration; 1967.

Coley BL, Higinbotham NL, Romieu C. Hemipelvectomy for tumors of bone: report of 14 cases. Am J Surg. 1951;82:27.

Dénes Z, Till A. Rehabilitation of patients after hip disarticulation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1997;115:498.

Endean ED, Schwarcz TH, Barker DE, et al. Hip disarticulation: factors affecting outcome. J Vasc Surg. 1991;14:398.

Ghormley RK, Henderson MS, Lipscomb PR. Interinnomino-abdominal amputation for chondrosarcoma and extensive chondroma: report of two cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1944;19:193.

Gordon-Taylor G, Monro RS. Technique and management of “hindquarter” amputation. Br J Surg. 1952;39:536.

Gordon-Taylor G, Wiles P, Patey DH, et al. The interinnomino-abdominal operation: observations on a series of fifty cases. J Bone Joint Surg. 1952;34B:14.

Karakousis CP, Vezeridis MP. Variants of hemipelvectomy. Am J Surg. 1983;145:273.

King D, Steelquist J. Transiliac amputation. J Bone Joint Surg. 1943;25:351.

Lazzari JH, Rack FJ. Method of hemipelvectomy with abdominal exploration and temporary ligation of common iliac artery. Ann Surg. 1951;133:267.

Littlewood H. Amputations at the shoulder and at the hip. BMJ. 1922;1:381.

Luna-Perez P, Herrera L. Medial thigh myocutaneous flap for covering extended hemipelvectomy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1995;21:623.

Masterson EL, Davis AM, Wunder JS, et al. Hindquarter amputation for pelvic tumors. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;350:187.

Pack GT. Major exarticulations for malignant neoplasms of the extremities: interscapulothoracic amputation, hip-joint disarticulation, and interilio-abdominal amputation: a report of end results in 228 cases. J Bone Joint Surg. 1956;38A:249.

Pack GT, Ehrlich HE. Exarticulation of the lower extremities for malignant tumors: hip joint disarticulation (with and without deep iliac dissection) and sacroiliac disarticulation (hemipelvectomy). Ann Surg. 1946;123:965. 124:1, 1946

Phelan JT, Nadler SH. A technique of hemipelvectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1964;119:311.

Pinzur MS, Angelats J, Bittar T. Salvage of failed amputation about the hip in peripheral vascular disease by open wound care and nutritional support. Am J Orthop. 1998;8:561.

Ross DA, Lohman RF, Kroll SS, et al. Soft tissue reconstruction following hemipelvectomy. Am J Surg. 1998;176:25.

Sara T, Kour AK, De SD, et al. Wound cover in a hindquarter amputation with a free flap from the amputated limb. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;304:248.

Senchenkov A, Moran SL, Petty PM, et al. Predictors of complications and outcomes of external hemipelvectomy wounds: account of 160 consecutive cases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:355.

Slocum DB. Atlas of amputations. St. Louis: Mosby; 1949.

Sorondo JP, Ferré RL. Amputación interilioabdominal. An Orthop Traumatol. 1948;1:143.

Troup JB, Bickel WH. Malignant disease of the extremities treated by exarticulation: analysis of two hundred and sixty-four consecutive cases with survival rates. J Bone Joint Surg. 1960;42A:1041.