Chapter 32 Amenorrhea, Oligomenorrhea, and Hyperandrogenic Disorders∗

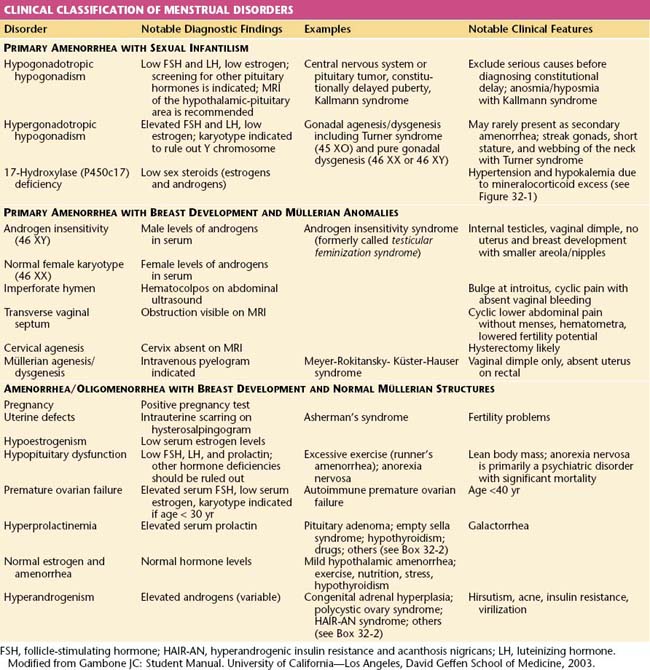

Amenorrhea, or the absence of menses, is a common symptom of several pathophysiologic states. This condition traditionally has been divided into primary amenorrhea, in which menarche (the first menses) has not occurred, and secondary amenorrhea, in which menses has been absent for 6 months or more. A more functional or clinical division of menstrual disorders based on initial history and physical examination would be as follows: primary amenorrhea with sexual infantilism, primary amenorrhea with breast development and müllerian anomalies, and amenorrhea and oligomenorrhea with breast development and normal müllerian structures. The last group includes disorders causing primary as well as secondary amenorrhea, oligomenorrhea, and the hyperandrogenic states (Table 32-1).

Primary Amenorrhea

Primary Amenorrhea

PRIMARY AMENORRHEA WITH SEXUAL INFANTILISM

Hypergonadotropic Primary Amenorrhea and Sexual Infantilism

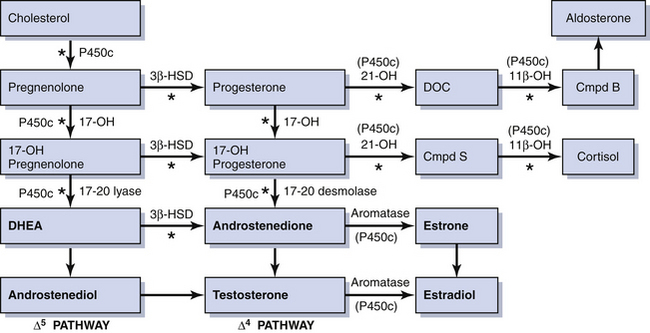

Rarely, some patients with primary amenorrhea and sexual infantilism have a defect of estrogen and androgen production. One example of this is a 17-hydroxylase (P450c17) deficiency, which prevents the synthesis of these sex steroids (Figure 32-1). These individuals have hypertension and hypokalemia caused by mineralocorticoid excess. Other patients, such as those with a 46 XY karyotype and Leydig cell agenesis, may lack the cells necessary for sex steroid production. Because the Leydig cells in the testicle are responsible for producing testosterone, these individuals are born with female external genitalia.

PRIMARY AMENORRHEA WITH BREAST DEVELOPMENT AND MÜLLERIAN ANOMALIES

Müllerian Dysgenesis or Agenesis

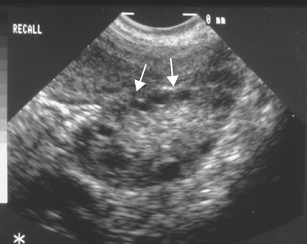

Patients with primary amenorrhea, breast development, and a 46 XX karyotype have levels of testosterone appropriate for females. This clinical diagnosis may be caused by müllerian defects that cause obstruction of the vaginal canal (e.g., imperforate hymen or a transverse vaginal septum) or by the absence of a normal cervix or uterus and normal fallopian tubes. An imperforate hymen should be suspected in adolescents who report monthly dysmenorrhea in the absence of vaginal bleeding (see Figure 18-7, pg 237). Clinically, these patients often present with a vaginal bulge and a midline cystic mass on rectal examination. Ultrasonography confirms the presence of a normal uterus and ovaries with a hematocolpos. These patients should be treated with hymenectomy.

Alternatively, women may present with similar symptoms but without a vaginal bulge. When ultrasonography confirms a normal uterus and ovaries, a transverse, obstructing vaginal septum (see Figure 18-8, pg 237) or cervical agenesis should be suspected. MRI is the diagnostic procedure of choice in these patients. If the MRI scan confirms a transverse septum, surgical correction is indicated. Surgical construction of a functional cervix is extremely difficult. In general, it is recommended that these women undergo hysterectomy.

Amenorrhea and Oligomenorrhea with Breast Development and Normal Müllerian Structures

Amenorrhea and Oligomenorrhea with Breast Development and Normal Müllerian Structures

All patients with menstrual bleeding disorders should be tested for pregnancy. Once pregnancy has been excluded, these individuals can be characterized as shown in Table 32-1. Initial history taking should include questions about the timing of thelarche, pubarche, and menarche. The timing and development of the menstrual disorder (present since puberty or new), significant weight change, strenuous exercise activities, dietary habits, sexual activity, concomitant illnesses or complaints, abnormal facial or body hair growth, scalp hair loss, acne, and the presence or absence of hot flashes and vaginal dryness should be noted. A comprehensive list of medications and dietary supplements taken should be obtained.

AMENORRHEA AND OLIGOMENORRHEA ASSOCIATED WITH HYPOESTROGENISM

Premature Ovarian Failure

Premature ovarian failure is defined as ovarian failure before the age of 40 years (see Chapter 35). When it occurs in patients younger than 30 years of age, ovarian failure may be caused by a chromosomal disorder. A karyotype is performed to exclude mosaicism (i.e., some cells bearing a Y chromosome). If cells with a Y chromosome are present, a gonadectomy to prevent malignant transformation is indicated.

AMENORRHEA AND OLIGOMENORRHEA WITH HYPERPROLACTINEMIA AND GALACTORRHEA

The consequences of hyperprolactinemia that are clinically significant include menstrual disturbances and galactorrhea. About 10% of women with amenorrhea have elevated prolactin levels, and a prolactin level should be measured in all cases of amenorrhea of unknown cause. Potential causes of elevated serum prolactin are noted in Box 32-1. Normal serum prolactin levels are less than 20 ng/dL, depending on the laboratory used. In patients with prolactin-secreting tumors, levels are usually more than 100 ng/dL. An elevated prolactin level should be confirmed by a second test, preferably in the fasting state because food ingestion may cause transient hyperprolactinemia. At the same time that the repeat prolactin level is drawn, a TSH level should be obtained to test for hypothyroidism because hyperprolactinemia may be seen in hypothyroid conditions.

Pharmacologic Agents Affecting the Secretion of Prolactin

A number of drugs may cause hyperprolactinemia and nonphysiologic galactorrhea (see Box 32-1).The mechanism of drug-induced hyperprolactinemia is secondary to reduced hypothalamic secretion of dopamine, depriving the pituitary of a natural inhibitor of prolactin release. When clinically indicated, patients with hyperprolactinemia caused by medications should be encouraged to discontinue the medication for at least 1 month. If hyperprolactinemia persists, or if the patient cannot interrupt the medication, a complete evaluation is indicated.

Amenorrhea and Oligomenorrhea with Hyperandrogenism

Amenorrhea and Oligomenorrhea with Hyperandrogenism

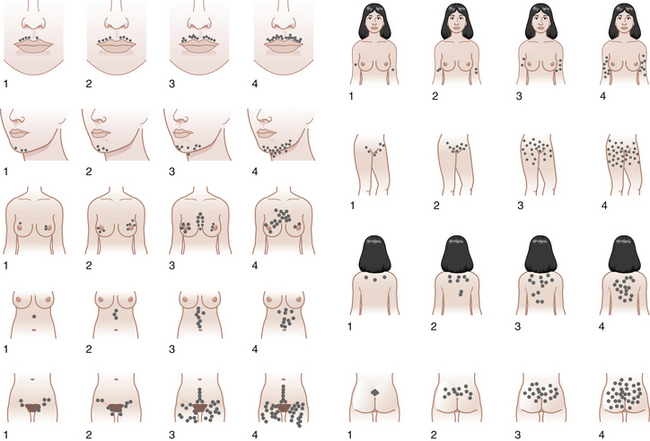

Hyperandrogenism is the clinical manifestation of elevated levels of male hormones in women. Features may range from mild unwanted excess hair growth and acne to alopecia (hair loss), more extensive hirsutism, and masculinization and virilization. Hirsutism is the presence of male-like hair growth caused by conversion of vellus to terminal hairs in areas such as the face, chest, abdomen, or upper thighs. Figure 32-2 illustrates a scoring system for hirsutism. Signs of masculinization include loss of female body fat and decreased breast size. Virilization is the addition of temporal balding, deepening of the voice, and enlargement of the clitoris to any of the previous signs of excess male hormone. Androgens in women are normally produced in the ovaries and the adrenal glands (see Figure 32-1, pg 357). Hyperandrogenic disorders may be divided into functional and neoplastic disorders of the adrenal or ovary (Box 32-2).

FIGURE 32-2 The Ferriman-Gallwey scoring system for hirsutism.

(Adapted from American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 140[5], Hatch R, 815-830, Copyright 1981, with permission from Elsevier.)

Hyperandrogenic Disorders

Hyperandrogenic Disorders

ADRENAL DISORDERS

Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia

Because 21-hydroxylase is responsible for the conversion of 17-hydroxyprogesterone to 11-deoxycortisol (compound S), a deficiency in 21-hydroxylase results in an excessive accumulation of 17-hydroxyprogesterone. As a result, this enzyme disorder is marked by an elevated serum 17-hydroxyprogesterone level as well as increases in its Δ4 metabolites androstenedione and testosterone (see Figure 32-1). This disease is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait.

OVARIAN DISORDERS

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

In most patients with PCOS, the ovaries contain multiple follicular cysts that are inactive and arrested in the mid-antral stage of development. The cysts are located peripherally in the cortex of the ovary (Figure 32-3). The ovarian stroma is hyperplastic and usually contains nests of luteinized theca cells that produce androgens. About 20% of hormonally normal women may also have polycystic-appearing ovaries.

Hyperandrogenic Insulin Resistance and Acanthosis Nigricans Syndrome

Hyperandrogenic insulin resistance and acanthosis nigricans (HAIR-AN) syndrome is an inherited hyperandrogenic disorder of severe insulin resistance, distinct from PCOS. HAIR-AN syndrome is characterized by extremely high circulating levels of insulin (>80 µU/mL basally or >500 µU/mL following an oral glucose challenge) due to severe insulin resistance. Because insulin is also a mitogenic hormone, these extremely elevated insulin levels result in hyperplasia of the basal layers of the epidermal skin, leading to the development of acanthosis nigricans, a velvety, hyperpigmented change of the crease areas of the skin (Figure 32-4). In addition, because of the effect of insulin on ovarian theca cells, the ovaries of many patients with the HAIR-AN syndrome are hyperthecotic. Patients with this disorder can be severely hyperandrogenic and even present with virilization. In addition, these patients are at significant risk for dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. These patients are particularly difficult to treat, although the use of long-acting GnRH analogues has been promising.

Ovarian Neoplasms

Androgen-producing ovarian tumors are extremely uncommon, occurring in about 1 in 500 hirsute women and include Sertoli-Leydig, hilus, and lipoid cell tumors and virilizing conditions associated with hyperplasia of the stroma surrounding non–hormone-producing ovarian neoplasms. These tumors include cystic teratomas, Brenner’s tumors, serous cystadenomas, and Krukenberg’s tumors (see Chapter 20).

Evaluation of Patients with Signs of Hyperandrogenism

Evaluation of Patients with Signs of Hyperandrogenism

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The degree of hirsutism (see Figure 32-2), acne, or androgenic alopecia should be assessed and the thyroid palpated for enlargement. Patients should be expressly asked about excess facial hair because they may conceal their hirsutism by waxing or electrolysis and be too embarrassed to volunteer the information. Evidence of cushingoid features should be noted. Acanthosis nigricans (see Figure 32-4) is a frequent marker of insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. A bimanual pelvic examination may identify ovarian enlargement. Asymmetric ovarian enlargement associated with the rapid onset of virilization can indicate a rare androgen-producing tumor.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Polycystic ovary syndrome. ACOG Technical Bulletin No. 41. Washington, DC: ACOG; December 2002.

Azziz R. The evaluation and management of hirsutism. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:995-1007.

Azziz R., Carmina E., Dewailly D., et al. for the Androgen Excess Society: Criteria for defining polycystic ovary syndrome as a predominantly hyperandrogenic syndrome: An Androgen Excess Society guideline. Position Statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4237-4245.

Azziz R., Carmina E., Sawaya M.E. Idiopathic hirsutism. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:347-362.

Azziz R., Dewailly D., Owerbach D. Non-classic adrenal hyperplasia: Current concepts. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;78:810-815.

Patel S.S., Bamigboye V. Hyperprolactinemia. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;27:455-459.

Amenorrhea and Oligomenorrhea with Normal Estrogen Levels

Amenorrhea and Oligomenorrhea with Normal Estrogen Levels