4 Alpha-hydroxy Acid Peels

Indications and Considerations in Performing a Glycolic Acid Peel

Preparing the Patient for the Glycolic Acid Peel

Once the patient is deemed a good candidate for the peel, a daily home care program of topical AHAs, in particular glycolic acid, should be advised. The topical glycolic acid home care products range from 8% to 20% concentrations. When starting this regimen on a patient who has never used the glycolic acid products, it is best to start at the low concentrations and increase as tolerated. In choosing the vehicle for the patient, it is best to match to the patient’s skin type. Cream formulations are preferred by patients with dry skin, gels by oily skin types and lotions by normal skin types. The product should be started nightly for the first 2 weeks then increased to twice daily as tolerated. This will help to determine if the patient has any unusual sensitivity to the glycolic acid prior to the administration of the peel. Also, the glycolic acid product will help to prepare the skin for the peel by allowing for prepeel desquamation. If the patient has any aversion to the appearance of desquamation or peeling per se, the peel should not be engaged. It is important to note that unusual sensitivity to glycolic acid is rare. The patient should also be apprised of the prepeel instructions found in Box 4.1

Box 4.1

Glycolic acid peel/acne wash preprocedure instructions

Upon completion of the prepeel counseling session, the patients should be instructed to arrive on the day of the peel with a clean face, free of make-up and moisturizers. Male patients should be informed not to shave on the day of the peel to prevent deeper penetration. Contact lenses should be removed after the consent forms are signed (Box 4.2 shows the form I use).

Box 4.2

Chemical peel consent

Consent

| I have read and understood the above, and I now authorize _________________________, to perform a glycolic acid chemical peel. | |

| ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ | |

| Signature of patient or legal guardian | Date |

| ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ | |

| Signature of staff witness | Date |

| ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ | |

| Signature of physician obtaining consent and witnessing patient’s signature | Date |

Peel Procedures

• Face peel procedure: supplies and technique

The equipment needed for a glycolic acid peel is in general readily available in a physician’s office, with perhaps a few exceptions. The required supplies include those listed in Box 4.3.

Postpeel Treatment and Instructions

After the treatment the patient is instructed to use a postpeel glycolic-acid-free moisturizer twice daily until the skin returns to normal appearance. A postpeel handout with these instructions reviewed immediately after the peel is given to the patient (Box 4.4). This may take anywhere from 1 to 7 days depending on the degree of peeling experienced. Strict photoprotective measures should be undertaken. If a patient is unwilling to follow photoprotective guidelines then further peels should be avoided. The patient is further instructed to stop all other products, especially retinoids, during this time period. The patient should be instructed to expect some tightening, peeling or desquamation, burning, itching, stinging, and edema in this recovery phase. However, many patients, especially those treated with low concentrations of the glycolic acid, never experience these symptoms. Nonetheless, even in the absence of gross peeling, it is best to reassure the patient about the success of the peeling procedure based on the microscopic exfoliation that occurs.

Box 4.4

Glycolic acid peel/acne wash postprocedure instructions

Following these guidelines will help accelerate the renewal process:

Adverse Reactions

• Epidermolysis

This can occur unexpectedly if a patient does not inform the physician that they have not discontinued their topical retinoids (Tazarotene, Adapalene, tretinoin), at least 1 week prior to the peel. This occurs because topical retinoids can enhance the penetration of the glycolic acid peel. Another risk of increasing peel penetration is prior treatment of the skin with aggressive scrubbing with loofahs or other exfoliating beads or puffs, or if microdermabrasion is employed immediately prior to the peel. Once epidermolysis does occur during the peel due to these situations, the patient may experience scabbing and should be informed that it may take up to a week for recovery to take place. Moisturization with glycolic-acid-free products is necessary and topical hydrocortisone may be employed, depending on the amount of irritation and edema. If severe edema occurs, a prednisone 6-day pack may be needed. Depending on the patient’s history, oral antiviral agents against herpes (Fig. 4.1), as well as oral antibiotics, should be considered. Topical antibiotic ointments such as Bactroban can be used on crusted areas to keep them moist.

• Hyper- or hypopigmentation

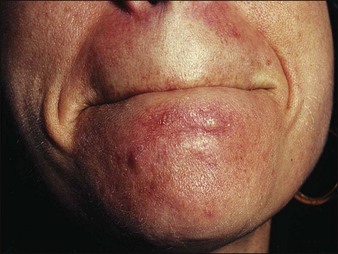

The risk of hyper- or hypopigmentation is increased if deep penetration occurs on scrubbed or rubbed sites. A perioral acneiform dermatitis has been noted in a small number of patients, particularly on the chin (Figs 4.2 and 4.3). This phenomenon is unexplained. Nonetheless, it should be treated as a perioral dermatitis and further peels avoided on the chin. Other rare occurrences are urticaria development but this responds to topical hydrocortisone (Fig. 4.4).

Conditions Treatable with Glycolic Acid Peels

• Photoaging

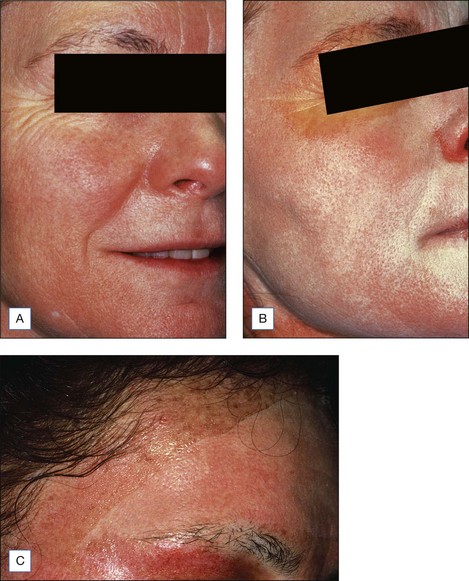

The use of glycolic acid peels in photoaging is meant to help to improve fine lines but not coarse wrinkles. In order to treat coarse wrinkles there are many options, but it is possible to use combinations of 70% glycolic acid peels immediately prior to 20% tricholoracetic acid (TCA) peels to enhance the benefit of the TCA without increasing TCA concentrations (Fig. 4.5).

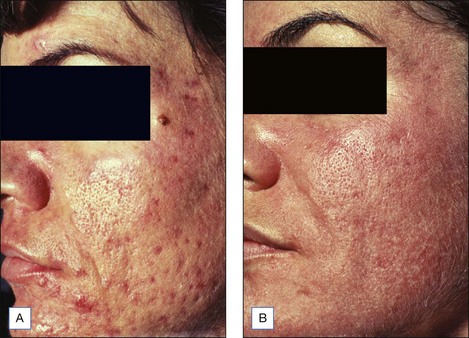

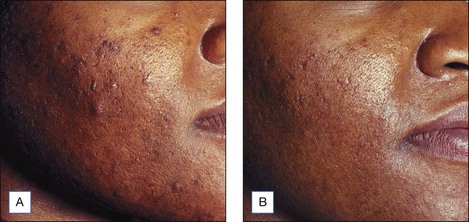

• Acne

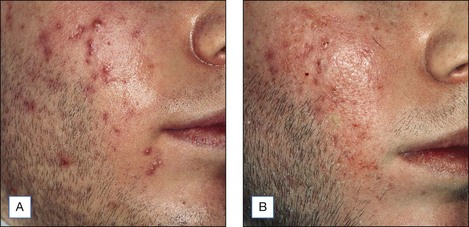

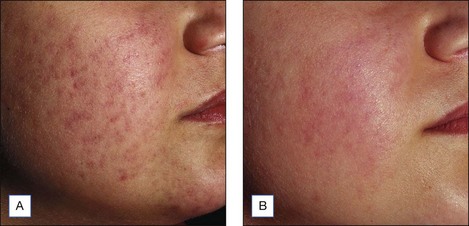

Since acne is a multifactorial condition it may be necessary to use combination therapies to achieve an improvement, especially in the case of comedonal, papular, and pustular subtypes. Glycolic acid peels have been proved to have an important role in the management of acne vulgaris. While it is by no means a solitary therapy nor an alternative to oral or other topical therapies, it is best recommended as a complementary treatment. The mechanism of action of glycolic acid peels in acne may be the promotion of exfoliation of the skin, thereby inducing a slough of the keratotic plug and reduction of microcomedone formation. Shallow acne scarring can also be improved, as well as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, if these peels are performed on a consistent and serial basis (Figs 4.6–4.10).

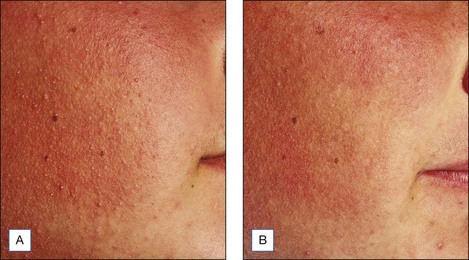

• Keratosis pilaris

Keratosis pilaris is amenable to treatment with glycolic acid peels of the face, upper arms, and thighs. The peels, especially in higher concentrations, can lead to desquamation and sloughing of the perifollicular keratotic lesions, thus yielding softer skin (Fig. 4.11). However, it is important to mention that the erythema generally associated with keratosis pilaris is not treatable with the glycolic acid peels. In addition, the condition will naturally recur as this is not a permanent treatment. It is best recommended that higher concentrations of glycolic acid lotions (12–20%) be used as maintenance therapy.

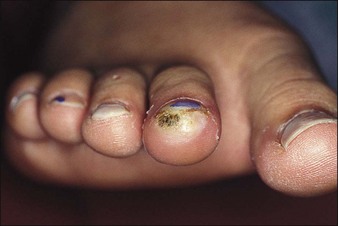

• Warts

Recalcitrant warts have posed a treatment challenge. Glycolic acid peel solution can be applied to a small cotton pledget to a wart after being taped onto the affected extremity site. The pledget is removed after 1 hour exposure, earlier if the patient experiences any stinging or irritation. It is best to apply Vaseline around the site to prevent leakage onto normal skin (Figs 4.12 and 4.13). The success of this treatment is really dependent on the compliance of the patient. Patients should expect peeling and possible blistering after this treatment and the aftercare is similar to that post liquid nitrogen.

• Actinic keratoses and actinic cheilitis

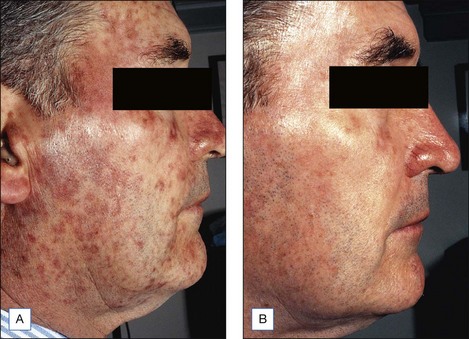

There are many treatment options for actinic keratoses, as listed in Table 4.1. Nevertheless, glycolic acid peels can be added to that list. The use of glycolic acid peels in combination with 5-fluorouracil is recommended to ensure treatment of the actinic keratoses. It is felt that alpha-hydroxy acids increase skin permeability and thereby may enhance penetration and increase the efficacy of 5-fluorouracil in the treatment of actinic keratoses (Figs 4.14 and 4.15). In addition, since AHAs increase desquamation, there may be reduced 5-fluorouracil-associated inflammatory reactions. I recommend that patients be pretreated with 5-fluorouracil 5% cream for 1 week prior to a 70% glycolic acid peel that is usually applied to the point of epidermolysis, which usually occurs within 2 minutes of treatment (Fig. 4.16). It is believed that the actinic keratoses treatment is initiated with the 5-fluorouracil 5% cream which then allows for selective treatment of actinically damaged skin by the glycolic acid peel. In a 1998 actinic keratoses study evaluating 18 subjects in a half-face, randomized, comparison it was reported that the combination of 5-fluorouracil cream with 70% glycolic acid peel provided a 92% therapeutical effect of treating actinic keratoses, compared to a 20% clearance with glycolic acid peels alone. 5-Fluorouracil cream alone eliminated about 75% of the actinic keratoses. Therefore, there is an increase in efficacy with a shortening of 5-fluorouracil cream exposure time, which appeals to many patients with photodamaged skin.

| Treatment options | Cosmetic and other issues |

|---|---|

| Cryosurgery: liquid nitrogen (most common treatment in US) | Risk of dyspigmentation, blistering, stinging |

| 5-FU alone | Pain or irritation, ulcer, burn, downtime, compliance issues |

| Electrodesiccation and curettage (ED&C) | Potential scarring, need local anesthesia |

| Jessner’s/TCA peel | Downtime, greater degree of peeling |

| Photodynamic therapy | Burning, stinging, photosensitivity |

| Laser resurfacing | Downtime, anesthesia, peeling, pain |

Bartolone J, Santhanam U, Penska C, et al. Alpha-hydroxy acid modulates skin cell biology. Chicago, Ill: Poster presentation, SID; 1996. May 18–24

Bernstein EF, Van Scott EJ, Yu RJ, et al. A pilot investigation of the effects of citric acid on viable epidermal thickness and dermal glycosaminoglycans. Chicago, Ill: Poster presentation, SID; 1996. May 18–24

Briden ME, Rendon-Pellerano MI. Treatment of rosacea with glycolic acid. Journal of Geriatric Dermatology. 1996;4:17-21.

Briden ME, Kakita LS, Petratos MA, Rendon-Pellerano MI. Treatment of acne with glycolic acid. Journal of Geriatric Dermatology. 1996;4:22-27.

Clark CP. Alpha hydroxy acids in skin care. Clinical Plastic Surgery. 1996;23:49-56.

Costello EJ, Filchone EM. Preparation and properties of pure ammonium DL lactate. Journal the American Chemical Society. 1953;75:1242-1422.

Ditre CM. Building your practice with glycolic acid peels. Skin and Aging. 1998:48-63.

Ditre CM. Glycolic acid peels. In: Dzubow LM, editor. Cosmetic dermatologic surgery. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998:43-52.

Ditre CM. Glycolic acid peels. Dermatologic Therapy. 2000;13:165-172.

Ditre CM, Nini KT, Vagley RT. Introduction: practical use of glycolic acid as a chemical peeling agent. Journal of Geriatric Dermatology. 1996;4:2-7.

Ditre CM, Griffin TD, Murphy GF, et al. Effects of alpha hydroxy acids on photaged skin: a pilot clinical, histologic and ultrastructural study. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1996;34:187-195.

Ditre CM, Nini KT, Vagley RT. Practical use of glycolic acid as a chemical peeling agent. Journal of Geriatric Dermatology. 1996;4(sb):2b-7b.

Greaves MW. Topical alpha-hydroxy acid derivatives for relieving dry itching skin. Cosmetics and Toiletries. 1991;105:61.

Griffin TD, Van Scott EJ. Case of pyruvic acid in the treatment of actinic keratoses: a clinical and histopathological study. Cutis. 1991;47:325-329.

Kakita LS, Petratos MA. The use of glycolic acid in Asian and darker skin types. Journal of Geriatric Dermatology. 1996;4:8-11.

Keenan WF. Comparative efficacy of two different formulations on xerosis [Letter]. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1990;23:769-770.

Klaus MV, Wehy RF, Rogers RS3rd, et al. Evaluation of ammonium lactate in the treatment of seborrheic keratoses. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1990;22:199-203.

Lavker RM, Kaidbey K, Leyden JJ. Effects of topical ammonium lactate on cutaneous atrophy from a potent topical corticosteroid. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1992;25:535-544.

MacEachern L, Rensjer K, Dickens M. The percutaneous absorption of glycolic acid in human skin. Chicago, Ill: Poster presentation, SID; 1996. May 18–24

Marrero GM, Katz BE. The new fluor-hydroxy pulse peel: a combination of 5-fluorouracil and glycolic acid. Dermatologic Surgery. 1998;24(9):973-978.

Perricone NV. An alpha hydroxy acid acts as an antioxidant. Journal of Geriatric Dermatology. 1993;1:101-104.

Piacquadio D, Dobry M, Hunt S, et al. Sort contact 70% glycolic acid peels as a treatment for photodamaged skin: a pilot study. Dermatologic Surgery. 1996;22:449-452.

Rendon-Pellerano MI, Bernstein EF. The use of glycolic acid in the management of xerosis and photoaging. Journal of Geriatric Dermatology. 1996;4:12-16.

Ridge JM, Siegle RJ, Zuckerman J. Use of alpha hydroxy acids in the therapy for photaged skin. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1990;23:932.

Sakaki S. Application of MTT test for screening of cell growth activators. Evaluation of alpha hydroxy acids. Journal of the Society of Cosmetic Chemists. 1993;27:116-119.

Siskin SB, Quinlan PJ, Finklestein MS, et al. The effects of ammonium lactate 12% lotion vs. no therapy in the treatment of dry skin of the heels. International Journal of Dermatology. 1993;32:905-907.

Smith HF, Seaton J, Fischer L. The single dose toxicity of some glycols and derivatives. Journal of Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology. 1941;23(6):259-268.

Smith W. Hydroxy acids and skin aging. Soap, Cosmetics, Chemical Specialties. 1993;9:55-76.

Stern EC. Topical application of lactic acid in the treatment and prevention of certain disorder of the skin. Urologic and Cutaneous Review. 1946;50:106-107.

Stiller MJ, Bartolone J, Stern R, et al. Topical 8% glycolic acid and 8% lactic acid creams for the treatment of photodamaged skin: a double-blind vehicle-controlled clinical trial. Archives of Dermatology. 1996;132:631-636.

Takahashi M, Machida Y. The influence of hydroxy acids on the rheological properties of stratum corneum. Journal of the Society Cosmetic Chemists. 1985;36:177-187.

Van Scott EJ. Alpha hydroxy acids: procedures for use in clinical practice. Cutis. 1989;43:222-228.

Van Scott EJ. The unfolding therapeutic uses of the alpha hydroxy acids. Mediguide to Dermatology. 1988;3:1-5.

Van Scott EJ, Yu RJ. Hyperkeratinization, corneocyte cohesion and alpha hydroxy acids. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1984;11:867-879.

Van Scott EJ, Yu RJ. Alpha hydroxy acids: therapeutic potentials. Canadian Journal of Dermatology. 1989;1:108-112.

Van Scott EJ, Yu RJ. Alpha hydroxy acids: science and therapeutic use. Cosmetic Dermatology. 1994;7(10S):12-20.

Van Scott EJ, Yu RJ. Modulation of keratinization with alpha hydroxy acids and related compounds. In: Frost P, Comez EC, Zaias N, editors. Recent advances in dermatopharmacology. New York: Spectrum; 1978:211-217.

Van Scott EJ, Yu RJ. Substances that modify the stratum corneum by modulating its formation. In: Frost P, Horwitz SN, editors. Principles of cosmetics for the dermatologist. St. Louis: Mosby; 1982:70-74.

Van Scott EJ, Yu RJ. Control of keratinization with hydroxy acid and related compounds. I. Topical treatment of ichthyotic disorders. Archives of Dermatology. 1974;110:586-590.