Chapter 20 Alopecia

Randall VA: Androgens and hair growth, Dermatol Ther 21(5):314–328, 2008.

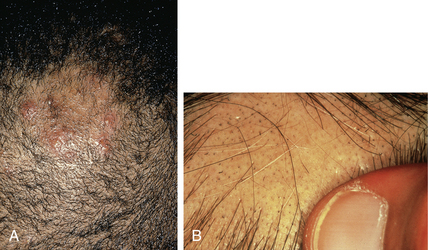

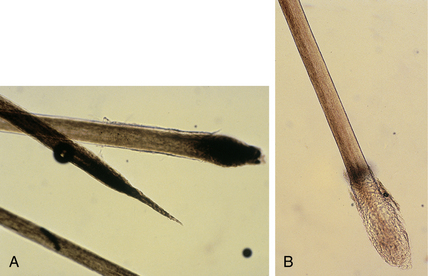

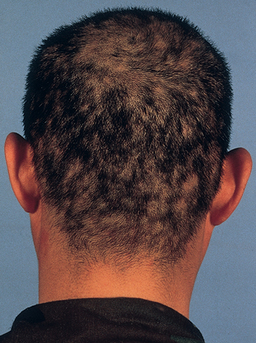

Alopecia areata also commonly affects children, but adults more often develop the condition. In alopecia areata, the affected areas may be totally hairless, but the scalp surface looks otherwise normal, without scaling and minimal, if any, erythema. A few short hairs may be present in the bald spot; these “exclamation mark” hairs tend to taper and lose pigment as they approach the scalp and may appear to float on the surface of the scalp (Fig. 20-2B).

Andrews MD, Burns M: Common tinea infections in children, Am Fam Physician 77(10):1415–1420, 2008.

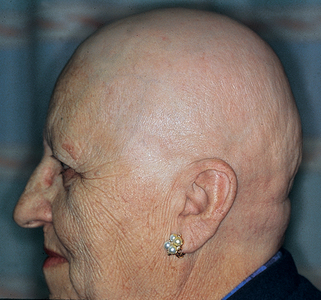

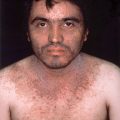

In telogen effluvium the metabolic and emotional “stress” of severe, debilitating illness causes many of the actively growing (anagen) hairs to enter the shedding (telogen) phase of hair growth prematurely. The hairs remain in telogen for about 3 months before they are finally shed (Fig. 20-5B), so there is always a “lag” time between the onset of severe disease and actual hair loss. Seldom is more than 50% of the hair shed in telogen effluvium, so patients develop thin hair but do not become completely bald. If the patient recovers and is no longer debilitated, hairs reenter the actively growing phase and the hair regrows.

Key Points: Alopecia

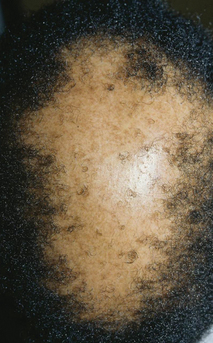

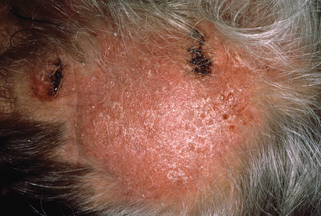

The second form of alopecia mucinosa occurs in patients with mycosis fungoides, a form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Patients are usually elderly, and numerous, often large, hairless, erythematous, and indurated plaques are found (Fig. 20-7). Histologically, follicular mucinosis is present, but an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate that often invades the epidermis and follicles is also seen. This atypical cellular infiltrate allows for the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides. The hairless lesions and histologic follicular mucinosis are merely manifestations of the underlying lymphoma.

Figure 20-7. Alopecia mucinosa occurring in a patient with mycosis fungoides.

(Courtesy of Fitzsimons Army Medical Center teaching files.)

Gibson LE, Brown HA, Pittelkow MR, Pujol RM: Follicular mucinosis, Arch Dermatol 138(12):1615, 2002.