CHAPTER 20 Alloplastic Contouring for Suborbital, Maxillary, Zygomatic Deficiencies

Alloplastic facial contouring has evolved from being an ‘ancillary procedure’ to a standard valuable tool in the armamentarium of aesthetic facial surgeons over the last 25 years. This author has pioneered most of the implants and techniques now used by surgeons worldwide.1 These have proven over time to create contour corrections of permanence and with minimum (less than 1%) morbidity. The many myths about alloplastic augmentation have been dispelled by the author from his 30 years of experience confirming that these techniques can now be used safely and effectively by any well-trained plastic surgeon who has an interest in 3-dimensional aspects of aesthetic facial surgery.

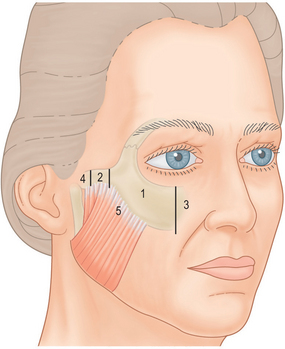

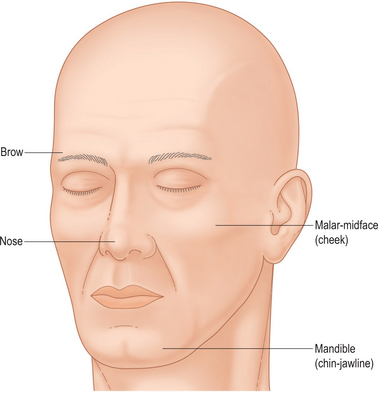

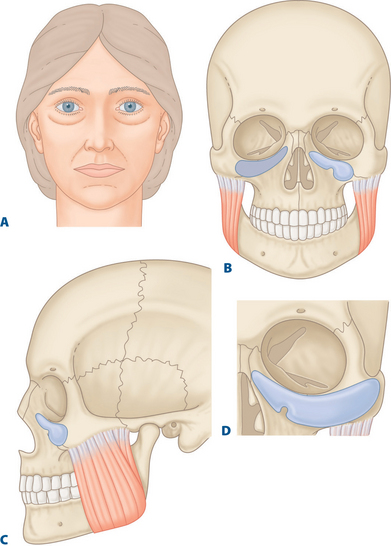

According to my original anatomic zonal concepts of the facial skeleton (Fig. 20-1) the suborbital zygomatic region is comprised of: (1) Zone 1, the major body of the malar bone defined medially from the infraorbital nerve and laterally by the beginning of the middle third of the zygomatic arch and (2) Zone 3, the paranasal suborbital zone which extends from the nasal bone – maxillary tissue to the infraorbital nerve. This zone contains the well-described ‘tear trough’ sulcus.

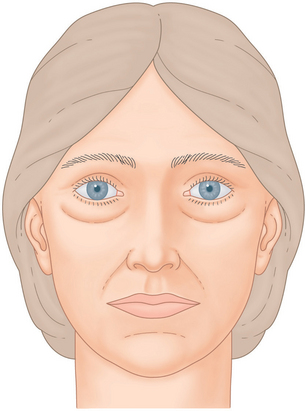

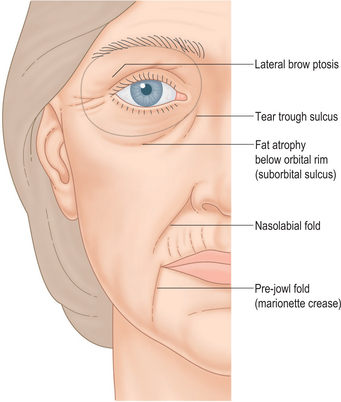

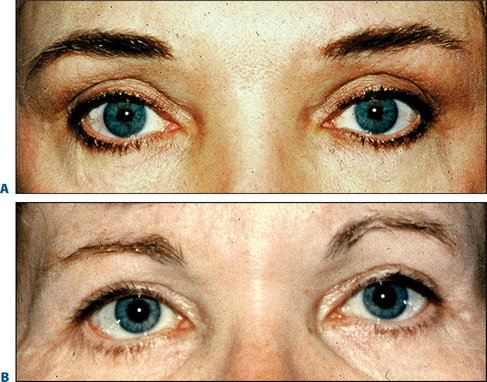

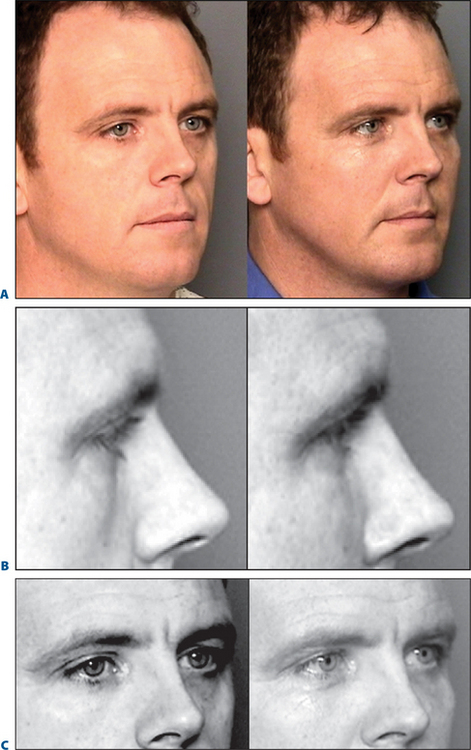

The suborbital region has commanded significant attention over the past 10 years due to the advent of upper midface suspension techniques designed to improve a tired, hollow appearance from the depression of the lid-cheek junction2,3 (Fig. 20-2) which occurs mostly with the aging process but also as a hereditary variant. Moreover, it has now been validly established by prominent investigators that the aging process of the upper midface results largely from atrophy or shrinkage of the volume of fat contained in the periorbital and malar region that is present in the youthful phases of life, birth to age 30 on the average4,5 (Fig. 20-3).

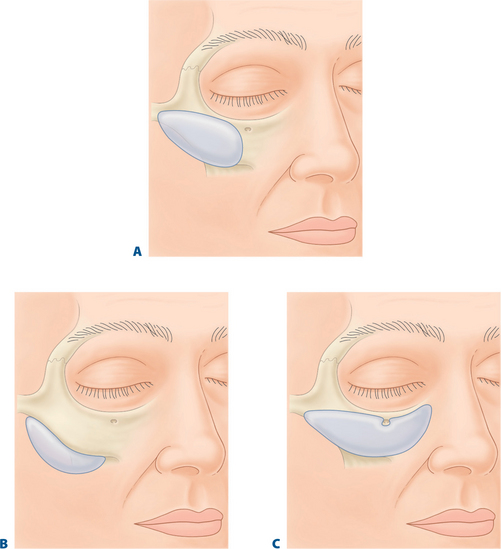

Alloplastic implants designed specifically for the suborbital tear trough malar region can eliminate the need for techniques using fat rearrangement in the inferior orbital and suborbital region (Fig. 20-4). These fat manipulations may produce undesired sequelae such as lower lid retraction (ectropion) and visible unattractive irregular ‘lumpiness.’

Historical background

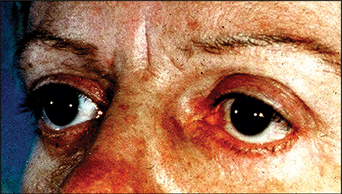

The importance of the lower eyelid-cheek junction has been appreciated by plastic surgeons over the past decade. In the early 1970s and 1980s, the standard surgical treatment for ‘tired eyes’ consisted of removal of fat and skin or skin and muscle from the lower eyelids.6 This universally produced either an unattractive vertical shortening of the lower lid or an accentuated hollowness under the eyes or both (Fig. 20-5). By the 1990s patients and surgeons alike began to realize that this original technique contributed to a haggard, unattractive periorbital appearance of aging.

Suborbital maxillary volume/malar suborbital deficiences

A medial sulcus just lateral to the nasal pyramid, which extends distally for 2.5 cm obliquely towards the angle of the mandible, has been termed a ‘nasojugal’ sulcus or ‘tear trough.’7,8 However, either by heredity or mainly with aging changes, this suborbital depression continues beneath the entire lower eyelid. This volume deficiency is not at the level of the inferior orbital rim as originally thought by plastic surgeons. Instead, it occurs consistently at a measured distance of 8 to 10 mm below the orbital rim. This observation was made by me early in the 1980s, when postoperative blepharoplasty patients began complaining about their more tired, ‘hollow’ look.

The etiology of why such a depression in this area appears as early as the third decade of life and certainly by the late 40s and early 50s has been unclear. Recently, however, largely through the photographic and computer studies of Lambros,4 it is now agreed upon that a true atrophy or involution of fat occurs in the upper two-thirds of the face and largely in the periorbital region. This disappearance of fat correlates with the increased appearance of a suborbital hollowness, which creates a tired, haggard appearance.

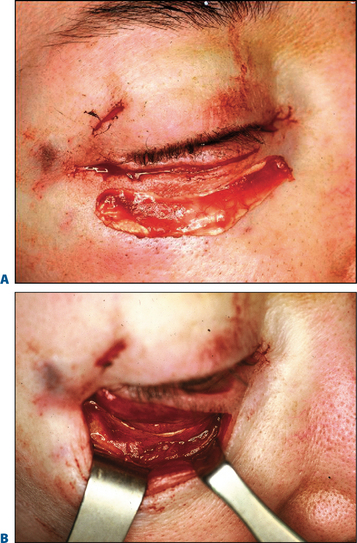

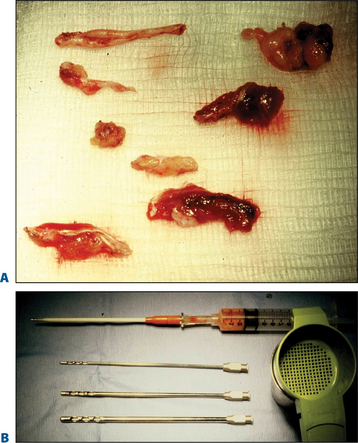

The treatment of the suborbital sulcus has been evolving for at least 25 years. In 1983, prompted by complaints of patients about the increased hollowness of their orbital region from traditional blepharoplasty I began transplanting autogenous tissues such as fat, temporalis fascia, temporalis muscle, and galea into the suborbital region below the orbital rim behind the orbicularis oculi muscle and over the SOOF tissues9 (Fig. 20-6). This area has now become recognized as the true area of deficiency, which produces a tired appearance from the fat atrophy, which accompanies aging.

Figure 20-6 A, Pieces of temporalis fascia, temporalis muscle and galea. B, Aspirated autologous fat.

My tissue transfer technique when a lower blepharoplasty was performed for ‘fat bags,’ the fat was excised tangentially from lateral to medial canthus, leaving a medial vascular pedicle. A small instrument such as a curved hemostat was introduced beneath the orbicularis muscle to tunnel from lateral to medial, grasping the fat pedicle and pulling it into the suborbital sulcus. When upper eyelid surgery was performed simultaneously, the strip of orbicularis muscle routinely removed, was also placed into the suborbital sulcus in a similar fashion. When combined with rhytidectomy, the author often used segments of temporalis fascia including muscle or even large amounts of galea and on occasion ear cartilage (Fig. 20-7). These procedures were performed in 150 to 200 patients at that time.

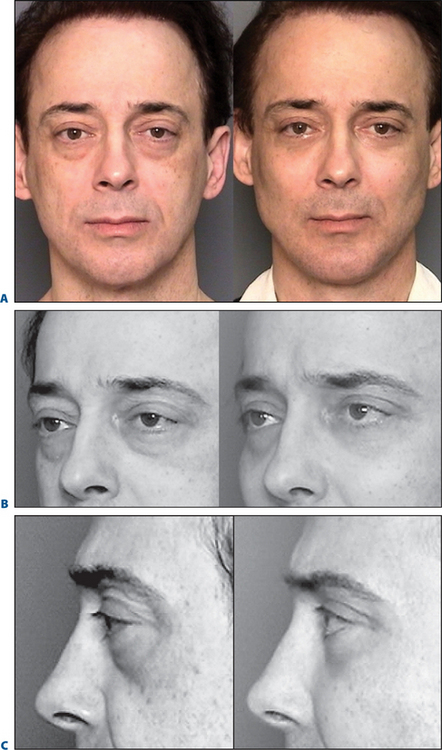

Although these transplantation methods could be demonstrated in the long-term (see photographs at six months to one year, Figs 20-8 & 20-9) the results were only partially successful in improving the suborbital sulcus with volume addition, assessed at a 50–70 percent improvement, 50–70 percent of the time. Lumps and irregularities using these tissue transplantation techniques were infrequent because the tissues were carefully distributed beneath the thickness and padding of the intact orbicularis muscle.

In 1998 Hamra10 (evolving from the work of Loeb),11 developed zygo-orbicular complex dissection techniques. At the same time subperiosteal midface suspension procedures evolved.2 These newer dissections elevated the orbicularis in the cheek above or below the periosteum and fat could be transposed over the orbital rim and sutured into the SOOF.12 A further refinement was the release and reset of the orbital septum.13

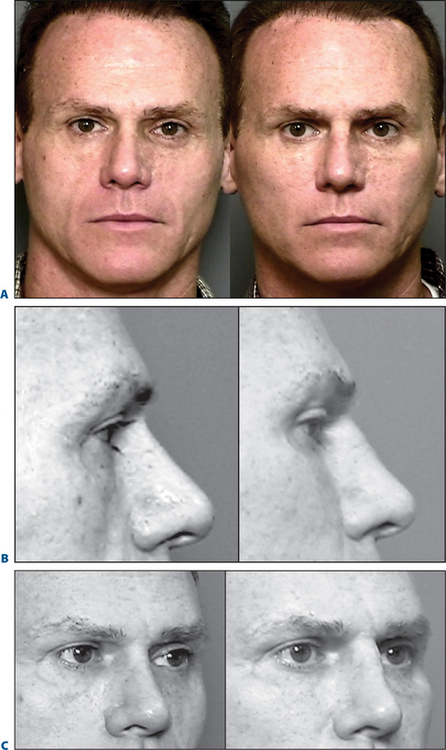

Elimination of the ‘tired look’ is very adequately accomplished with upper midface suspension because it provides the advantage of elevating the lower, thicker tissues of the cheek up over the thin suborbital sulcus adding additional thickness to the transposed fat thus providing a most consistent and excellent blending of the lid-cheek junction (Figs 20-10 & 20-11). A suborbital tear trough malar implant with transverse dimensions of 6 cm, a vertical dimension of 3.2 cm and a thickness of 3 or 4 mm will also blend the lid–cheek junction well without the need for an extensive midface submalar and lateral orbital temple brow dissection required for an upper and mid face ‘lifting’ procedure.

The alloplastic solution

In the early 1980s, I conceived of an implant designed to fill the inferior orbital rim and suborbital sulcus. Flowers by the 1990s8 carried this thought forward and his present day tear trough implants were developed and are obtainable through Implantech Corporation, Ventura, California.

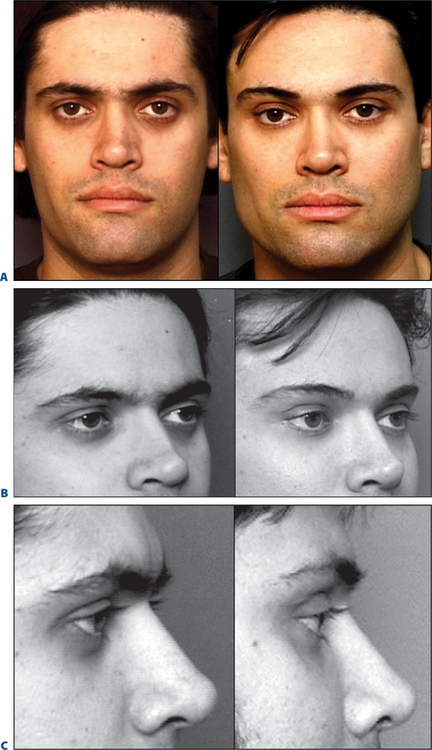

It became obvious to me that a significant percentage, probably at least 50 percent of patients with a tired, suborbital appearance, especially in the age group below 50 years, have an associated suborbital bony and malar deficiency. Therefore, the concept of a comprehensive suborbital malar shell or a malar tear trough implant seemed optimal to solve this problem in many individuals (Fig. 20-12).

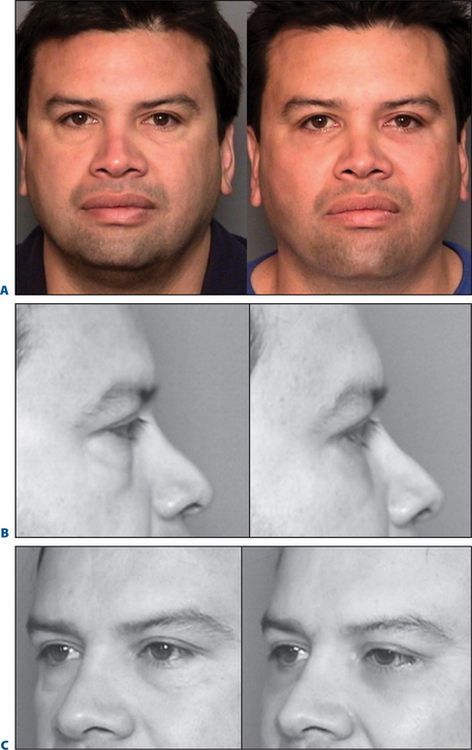

The suborbital tear trough malar implant has proven highly successful in approximately 20 patients over the past 18 months (Fig. 20-13). There has been a great increase in the number of patients who in consultation complain of a tired appearance, consisting of the anatomic features described above.

Facial balance

Facial aesthetics depends on facial balance. The interrelationship of the volume–mass elements of the face constitutes the basis for attractiveness, which we perceive as ‘beauty.’ The major volume–mass elements of the face are (1) the upper one third forehead segment; (2) the malar midface middle-third segment; (3) the nose volume prominence; and (4) the lower third mandibular jaw line segment (Fig. 20-14).

In aesthetic facial surgery, alterations of volume and mass can be successfully and permanently produced with alloplastic augmentation. Although autologous techniques, i.e. fat (fascia, muscle, etc.) are used and can achieve some degree of permanence, controversy still exists as to whether or not these autologous tissue changes can be permanent. Such autologous techniques need multiple treatments and donor site operations. Moreover the percentage of successful volume augmentation with each technique is unpredictable from patient to patient. These procedures do not lend themselves to the needs of today’s cosmetic surgery patients who are oriented towards minimally invasive techniques, which do not remove them very long or repeatedly from the mainstream of either their social or professional lives. In addition autologous fat injection techniques produce extensive and extreme swelling and discoloration, which can persist for months. It is a well known fact that edema of the midface requires much longer to subside than that of the chin or jaw line region.

Upper midface suspension

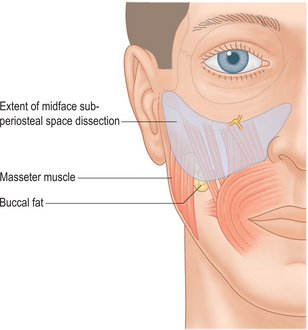

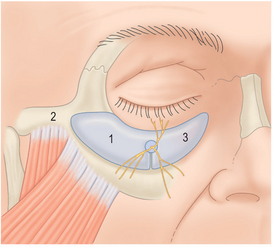

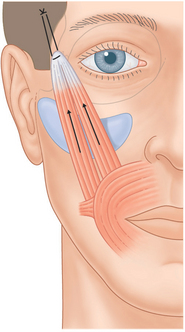

If a subperiosteal midface suspension technique is intended, the dissection is simply extended up along the lateral orbital rim. This is done in combination with a lateral temple brow dissection done through a limited access temporoparietal incision of approximately 7–10 cm. The tunnel created permits access to suspend the midface using a 3-0 PDS suture and securing it to the temporalis fascia (Fig. 20-15). The midface dissection is done to liberate the soft tissue layers from the malar bone on the subperiosteal level and also down onto the surface of the masseter muscle to the level of the buccal space. The inferior limit of the dissection is the buccal fat pad (Fig. 20-16).

Figure 20-15 The upper midface suspension secures the midface myocutaneous flap to the temporalis fascia under maximum tension.

The periorbital region

As previously mentioned the periorbital region has traditionally been of great concern to plastic surgeons. Operations removing skin and fat from the upper and lower eyelids conclusively produce more of an unattractive aging effect because the orbit becomes depleted of volume from both the surgery and the natural aging process. Highly unattractive and deforming alterations of the lower lid are common with traditional blepharoplasty techniques (Fig. 20-17).

Association of malar and suborbital deficiencies

Dr. Jelks reported that a recessive orbital rim which he termed a ‘negative vector’ suborbital deficiency accentuated the appearance of both the protrusion of fat in the lower eyelid as well as the ocular globe itself, thereby creating a non-attractive and tired/aging appearance.14

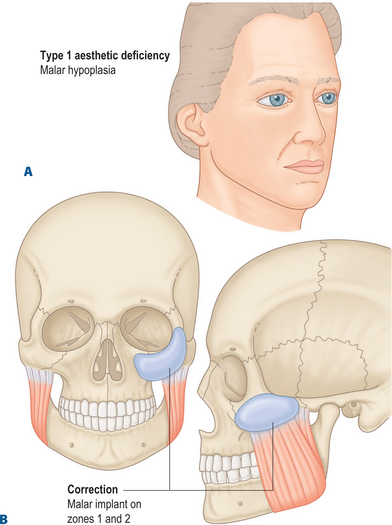

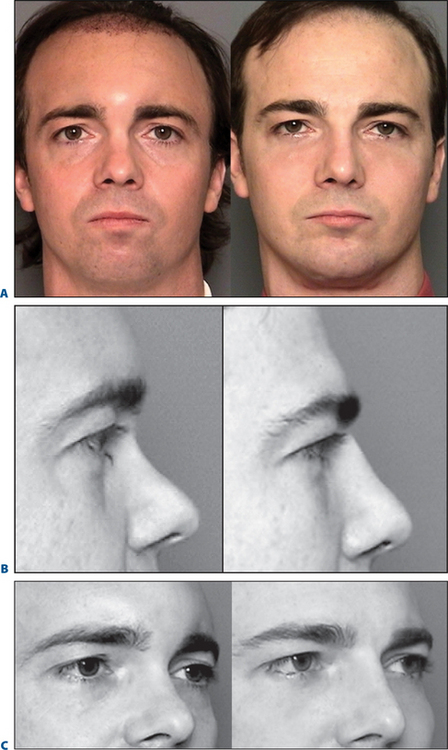

Many, if not most patients with a suborbital maxillary deficiency have an associated malar zygomatic deficiency. This has been defined as a type-1 face.15

A type-1 face has a regional volume deficiency in the malar-zygomatic region but has adequate fullness in the submalar lower midface cheek region (Fig. 20-18). This upper malar zygomatic deficiency is largely a skeletal deficiency, and therefore, augmentation of the entire suborbital malar-zygomatic region with an anatomic alloplastic implant is an obvious solution for resolving this deficiency (Fig. 20-19).

The natural junction between the thicker skin and subcutaneous fat of the cheek with the thinner lower eyelid skin where the subcutaneous fat is sparse creates an abrupt change in the lid–cheek junction along the entire suborbital region. This has been recently described as a tear trough or a suborbital lid–cheek dysjunction.8 The obvious solution is to volume-fill this region and alleviate this cosmetic deficiency, while simultaneously providing augmentation to the zygomatic-malar area in the many patients where this is also indicated.

A recent popular two-layer approach is to perform a subperiosteal midface suspension to elevate the thicker subcutaneous tissues and skin into that area, while transposing orbital fat over the infraorbital rim to provide a second deeper layer. These two procedures in combination provide excellent volume filling and a smooth youthful lid–cheek junction (Fig. 20-20). It must be understood, however, that such surgeries are technically sophisticated and have greater risks of undesirable lower lid sequelae especially in the hands of inexperienced surgeons.

Tear trough suborbital implant: technique

Placement of tear trough suborbital malar implants can be performed for the correction of:

There are four basic approaches. These are:

Subciliary placement

An incision is made 3 mm below the lash line limited in length and never extending beyond the lateral orbital rim. This can be placed (1) only below the eyelid to correct an isolated tear trough; or (2) extended only to the lateral orbital rim for a larger suborbital malar implant placement.

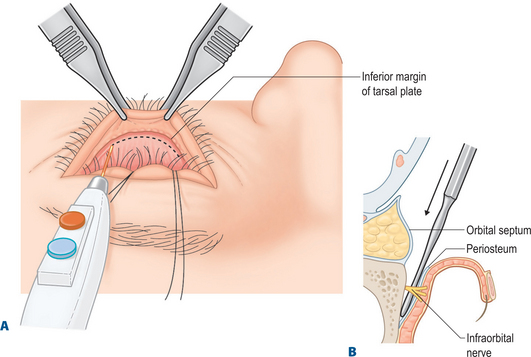

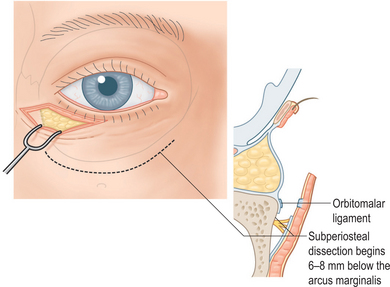

A skin muscle flap is elevated preserving 5–7 mm of pretarsal muscle below the tarsal lash line. Dissection is performed using a Freer elevator to facilitate preservation of the orbital septum. This dissection reaches the orbital rim and in its lateral two-thirds continues anteriorly over the orbital rim, but below the orbicularis muscle into the SOOF layer (Fig. 20-27).

Figure 20-27 A subcilial approach is used by making a 2-cm lateral subcilial incision only to the orbital rim.

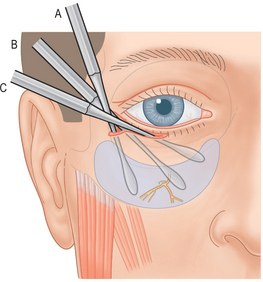

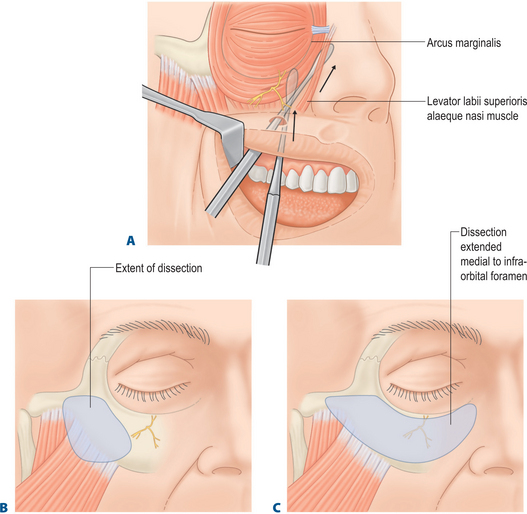

The infraorbital nerve trunk is isolated about 5–8 mm (variable) inferior to the orbital rim. A subperiosteal dissection is done, medial, lateral, and inferior to it. This should be accomplished under direct vision and with small curved elevators (Fig. 20-28).

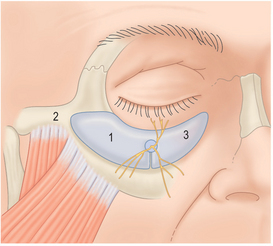

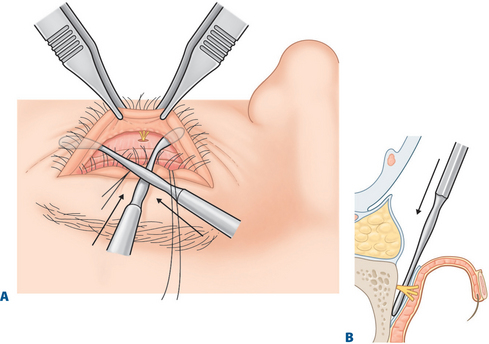

The chosen implant is then placed into the lateral pocket and seated along the infraorbital rim. The medial implant is positioned around the orbital nerve after a keyhole is created using a #11 scalpel blade to permit the infraorbital nerve to comfortably be surrounded by the implant. The slot of the keyhole is cut inferior to the infraorbital trunk (Fig. 20-29). The implant is positioned accurately medial to the tear trough, laterally along the orbital rim, and out onto the malar maxillary bone. Often, medial trimming needs to be accomplished, so that the most nasal portion of the implant is not buckled up into the narrow space of the lateral nasal bone in the medial canthal area. Three 4-0 or 5-0 Vicryl sutures are used to secure the implant to the orbital rim, one medial to the infraorbital nerve and two lateral.

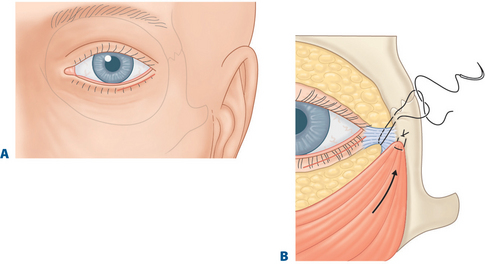

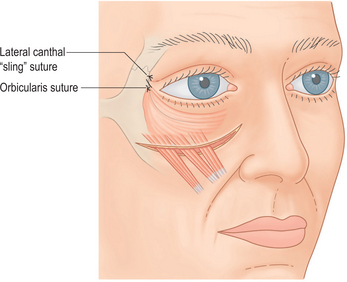

A standard lower eyelid closure is done and a lateral canthopexy is also routinely performed. The author’s chosen technique is a canthal sling, which incorporates a 4-0 black nylon loop around the canthal tendon two-thirds of the distance from the orbital rim to the anterior canthal skin surface. This suture is secured just lateral to the tendon into the orbital periosteum or at a precise distance measured by a caliper and marked with methylene blue anywhere from 2–5 mm up on the orbital rim (Fig. 20-30).

When the lower eyelid needs special tightening or there is a patient desire to have their palpebral aperture altered to create a more ‘almond-shaped’ elongated appearance, a second skin muscle suture of 4-0 Vicryl is placed into the orbicularis of the skin muscle flap and secured to the level where the lateral canthal tendon has been lifted. This suture is also placed firmly into the periosteum (Fig. 20-31).

Seldom is it necessary to resect more than 3–4 mm of skin and muscle. When the incision is lateral to the orbital rim this portion is closed with two or three 6-0 black nylon sutures. The subcilial incision is closed with a continuous 6-0 plain catgut suture.

Transconjunctival approach

The second approach to placing a suborbital tear trough malar implant is by means of a transconjunctival incision. The incision is made from inside the lower eyelid after adequate infiltration with a solution of 0.5 percent lidocaine containing 1 : 200,000 epinephrine. A 27-gauge needle is used to inject while retracting the eyelid with a double hook. Ten minutes is allowed for vasoconstriction. The electrocautery needle is then used to incise the mucosa for a distance of 3 cm starting approximately 3 mm from the lateral canthus and extending to 4 mm from the medial canthus (Fig. 20-32). This incision is made approximately 8 mm below the lash line just at the lower border of the tarsal plate. Using a blunt tenotomy scissor, the muscles are penetrated in the lateral portion of the incision to avoid the infraorbital nerve. The scissors are aimed to a point several millimeters below the orbital rim and are spread. A retraction suture of 4-0 nylon is placed through the posterior mucosal fornix after penetration. It is pulled up and sutured to the mid forehead to provide better visualization. A blunt scissor or needle holder is placed into the aperture and spread medially and laterally. The depressor muscles are divided with the electrocautery over the scissor. This brings the operating surgeon into the retro-lid space and above the orbital septum. An attempt is made not to disrupt the orbital septum, so that the fat will be contained posteriorly during the dissection. This is necessary to place the implant on the bone. This also facilitates visualization. If the orbital septum is penetrated, retraction of the orbital fat will be necessary using a malleable retractor and the procedure will be more difficult. Globe protectors are used for all transconjunctival surgery.

The origins of the orbicularis oculi are incised medially beneath the ‘tear trough’ leaving a cuff of arcus marginalis. Then the dissection is performed laterally elevating the orbicularis muscle while leaving an adequate SOOF layer. The subperiosteal portion of the dissection is carried out as previously described for a subcilial incision approach (Fig. 20-33). Placement of either a tear trough implant or a larger suborbital tear trough malar implant has also been previously described. A two or three suture 6-0 plain catgut subcuticular closure is used for the transconjunctival incision.

Intraoral approach

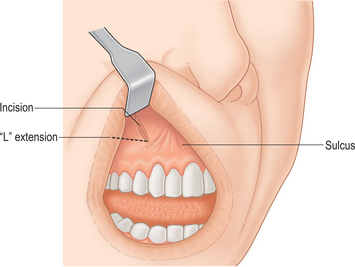

The third approach to suborbital implant placement consists of the intraoral route. Here, after adequate infiltration of the malar bone and maxillary buttress, a 1-cm incision is made obliquely through mucosa only at the location of the canine teeth. A second 1–1.5 cm lateral limb is made above the gingival buccal sulcus leaving a cuff of mucosa and muscle. This creates an L-shape incision on the left side and a reverse L on the right side (Fig. 20-34). A small elevator is used to penetrate the inferior portion of the incision directly onto the maxillary bone. An upward outward subperiosteal dissection is performed changing to a larger 1.5 cm spatula elevator going up the buttress of the maxilla and onto the suborbital region.

A medial dissection is also made beneath the infraorbital nerve and up to the medial canthal region staying below the periosteum (Fig. 20-35). The lateral dissection over the malar bone is done identically as for a malar implant placement. Direct visualization must be accomplished with a fiberoptic Aufricht light retractor to see the infraorbital nerve and dissect superiorly along the orbital rim. A tear trough or a suborbital malar implant is inserted with a forceps by first placing the lateral portion and then reaching around the inferior orbital nerve superiorly with a small mosquito clamp to pull the medial portion over the top of the infraorbital nerve. Prior to placement, a ‘keyhole’ segment has been removed at the site of the infraorbital nerve to prevent undesirable compression of the main trunk or branches.

Conclusion

A volume fill 4-mm suborbital implant or an extended suborbital malar tear trough implant, can restore suborbital and malar volume without upper midface suspension or fat translocation techniques (Fig. 20-36). Protruding infraorbital fat which creates tired ‘bags’ can easily be sutured to the external surface of the implant to establish a smooth lid–cheek junction.

1 Terino EO. Alloplastic facial contouring: Surgery of the fourth plane. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1992;16:195-212.

2 Ramirez OM. The subperiosteal rhytidectomy: The third generation face lift. Annual Plast Surg. 1992;28:218.

3 Hamra ST. Frequent facelift sequelae: Hollow eyes and the lateral sweep: Cause and repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:5.

4 Lambros SV. Aging, facial shape and fat injection. In: Terino EO, Flowers RS, editors. The Art of Alloplastic Facial Contouring, Chapter 15. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 2000:221-238.

5 Coleman SR. Structural Fat Grafting. St Louis: Quality Medical Publishing, 2004.

6 Rees TD. Blepharoplasty, Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, Volume II. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1980;457-580.

7 Duke-Elder S. The Anatomy of the Visual Systems. System of Ophthalmology Series, vol 2. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1961.

8 Flowers RS. Tear trough implants for correction of tear trough deformity. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20-22:403-414.

9 Terino EO: Periorbital Tissue Transplantation. Presentation at Facial Surgery Symposium, San Diego, CA, 1987.

10 Hamra ST. The zygorbicular dissection in composite rhytidectomy: An ideal midface plane. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:5.

11 Loeb R. Fat pad sliding and fat grafting for leveling lid depressions. Clin Plast Surg. 1981;8:4.

12 Hamra ST. The role of orbital fat preservation in facial aesthetic surgery: A new concept. Clin Plast Surg. 1996;23:17-28.

13 Hamra ST. The role of the septal reset in creating a youthful eyelid-cheek complex in facial rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:2124.

14 Jelks GW, Jelks EB. Peck GC, editor. Complications and Problems in Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, Chapter 5. Gower Medical Publishing, London, 1992;58.

15 Terino EO. Aesthetic facial typing by zonal deficiencies and preoperative planning. In The Art of Alloplastic Facial Contouring, Chapter 4. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 2000;49-63.