Chapter 58 Alligator and Crocodile Attacks

For online-only figures, please go to www.expertconsult.com ![]()

Crocodilians have inundated cultural media from traditional folklore to modern television.25 In addition to their fearful appearance, they are one of the few animal species that will attack and kill humans.20 Evidence can be found in paleontologic references that crocodilians preyed on human ancestors.7 Crocodilians have been feared and worshiped in ancient societies such as the Australian Aborigines, Iban people of northern Borneo, Cambodian villages, ancient Egyptians, and Native Americans.3 Following World War II, alligators were increasingly hunted, and because of a decline in numbers, were listed in 1967 on the endangered species list. Following federal protection, they were removed from the list in 1987; alligator populations in the southern United States have since increased.15 Many populations of crocodilians, however, have not fully recovered. With rising human inhabitation around coastal zones of Australia and the southern United States, human–crocodilian interactions are likely to increase.5

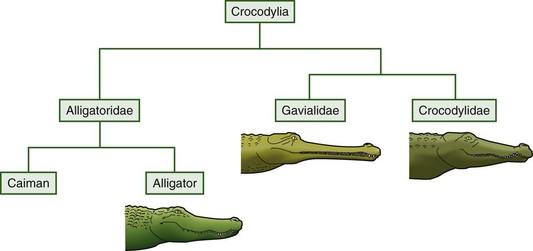

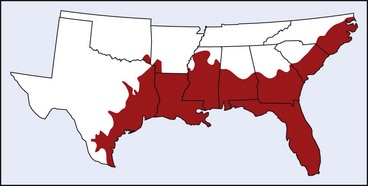

Crocodiles, alligators, and caimans are all parts of the reptilian order Crocodylia, comprising a total of 23 species separated into three families: Alligatoridae (with 8 species, including alligators and caimans), Crocodylidae (14 species, including the crocodiles), and Gavialidae (including the Indian gharial) (Figure 58-1).3 Crocodilians date to the time of the dinosaurs and are one of the oldest living members of the reptile family. Alligators and caimans belong to the same crocodilian order, and both have shorter, wider snouts than do crocodiles.8 When an alligator or caiman is seen with a closed mouth, its upper jaw hides the fourth, lower tooth. Some species of caimans have bony ridges, called spectacles, between the eyes.8 Three such species of crocodilians (genus Crocodylus) and alligators (genus Alligator) exist in the United States, two native and one foreign.28 The American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis [Figure 58-2, A]) is the most common species and found in most southern states, including Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Louisiana, Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, Texas, Oklahoma, and likely Tennessee (Figure 58-3). The American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus [Figure 58-2, B]) is found only in south Florida. The non-native caiman (Caiman crocidilus [Figure 58-2, C ]) is becoming increasingly established in south Florida.16

(A Courtesy Brad Weinert; B courtesy Gerard Caddick and Terra Incognita; C courtesy George Hertner.)

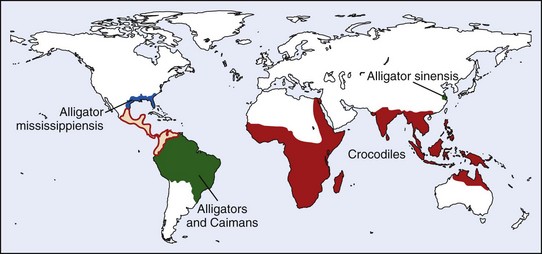

Worldwide, crocodilian habitats include southern United States, Central and South America, sub-Saharan Africa, India, Sri Lanka, southern China, the Malay Archipelago, Palau, the Solomon Islands, and northern Australia (Figure 58-4). Larger species of crocodiles include the saltwater and Nile crocodiles. These are notoriously the most dangerous, reportedly killing hundreds of people every year in Africa and Southeast Asia.5

Characteristics, Lifestyle, and Habits

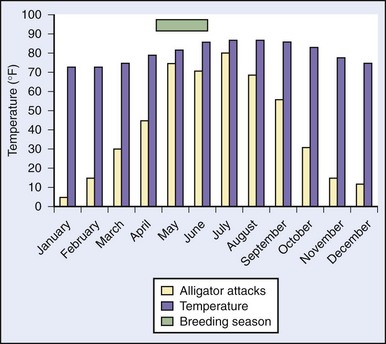

The crocodile family dates back 225 million years to the Mesozoic Era. Crocodilians evolved, along with modern birds, from a group of animals known as thecodonts. Crocodilians can live in captivity up to 66 years of age, with most living up to 50 years of age in the wild.8 Crocodilians vary in size, but in general males are larger than are females, with the most growth occurring during the first two years of life. For example, the American alligator reaches a maximum adult size of 4.5 m (14.8 feet) and the American crocodile 6 m (19.7 feet). The common caiman reaches 2.8 m (9.3 feet). The notorious Nile crocodile reaches 5.5 m (18 feet) and the saltwater crocodile 7 m (23 feet) (Table 58-1).8 Breeding season is typically late May or early June, with females laying clutches of 30 to 50 eggs. Their diet is predominantly carnivorous, and includes fish, snails, birds, small mammals, frogs, and crustaceans.

| Species and Latin Name | Maximum Adult Male Size |

|---|---|

| American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) | 4.5 m (14.8 feet) |

| American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) | 6 m (19.7 feet) |

| Australian freshwater crocodile (Crocodylus johnsoni) | 3 m (10 feet) |

| Black caiman (Melanosuchus niger) | 4.6-6 m (15-19.7 feet) |

| Common caiman (Caiman crocodilus) | 2.8 m (9.3 feet) |

| Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) | 5.5 m (18 feet) |

| Saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) | 7 m (23 feet) |

Data from Dudley K: Alligators and crocodiles, Calgary, 1998, Weigl Educational Publishers Limited.

Crocodilians, like all reptiles, are ectothermic (cold-blooded). They rely on their environment for body temperature, and as a result, their activity level depends greatly on the time of day. In hot climates, crocodiles keep cool during much of the day by staying underwater, before they move onto land during the night. They may remain submerged for more than an hour. They may also be found in mud burrows close to the water’s edge as they lay their eggs or retreat from the water during colder months. Special adaptations make them superior predators in the water environment, preferring slow moving water to preserve their sense of smell when submerged. Crocodilians in cool climates bask in the sun to stay warm.8 Crocodilians may also rest with the mouth open, using the thin skin inside the mouth as a radiator to increase cooling.

Crocodilians are largely nocturnal creatures, using their characteristic slit-like eyes to make use of more light than does a round pupil.8 A third eyelid helps protect their eyes while they swim underwater, making them more effective hunters in murky water. Watertight nostrils on the distal end of their long snouts allow an impeccable sense of smell, even when the majority of the body is completely submerged under water. Crocodilians have roughly 28 to 32 teeth in the lower jaw and 30 to 40 teeth in the upper jaw. These teeth are excellent for grabbing and tearing, but cannot be used for chewing. Thus, crocodilians must tear their prey into pieces before swallowing them. Broken teeth are replaced by new teeth growing under exiting teeth, in a manner analogous to that of sharks.8 The jaws of the American alligator were noted in one study to produce the biting force of 1000 kg (2.2 tons).3 This is enough force to crush large bones and shells. Opposing muscles used to open these massive jaws, however, are quite weak and easily kept closed by human arms, as depicted by popular television and alligator tourist shows.

Feeding and Predation Habits

Crocodilians have peg-like teeth well adapted for catching and holding onto prey. However, the teeth are not well suited for chewing, so most prey is killed and allowed to rot, which makes it easier to swallow.28 Once captured, prey is often completely neutralized by being crushed by the attacker’s powerful jaws. Larger prey animals are often attacked at the lower extremities, throwing them off balance prior to their being dragging into the water and drowned. Once overtaken, smaller animals are swallowed whole. Violent thrashing of the crocodilian head from side to side dismembers larger prey. Further attempts of separating smaller pieces are accomplished by rolling the prey over and over underwater, the so-called “death roll.”28 As a result, victims of crocodilian attacks are generally severely disfigured with significant crush injuries.20

Attacks

Most crocodilian attacks occur “out of the blue” as the attacking animal utilizes a sudden burst of speed and the advantage of surprise.6 An adult crocodile can devour prey much larger in size than a human. According to one report, the stomach of an Australian estuarine crocodile contained the remains of an aborigine and a 4-gallon drum containing two blankets. The crocodile can travel in water at a speed of 32 km/hr (20 mph) and can charge a short distance over land at 24 to 48 km/hr (15 to 30 mph). The enormous jaws and canine teeth can bite with sufficient force to sever an outboard boat propeller. Feeding in freshwater rivers and adjacent land has introduced them to cows, horses, and humans, who are attacked when they cross rivers, catch fish, draw water, or work in the fields.27 Alligators residing in lakes and ponds associated with golf courses, parks, and tourist attractions have attacked humans in the United States.25

A study in the United States analyzing crocodilian attacks between 1928 and 2009 identified that 567 adverse encounters and 24 deaths had been reported. It is estimated that these events are largely underreported, and may not be representative of notably higher incidence in other countries. Most fatalities are reported in Florida, followed by Texas, Georgia, and South Carolina.16 Severe injuries described as life or limb threatening represented only 11.8% of cases. Attacks in most instances were only a single bite (81%). Victims were more likely to be males (85.4%) and adults 18 years of age or older (78.6%).16 Most injuries were classified as lacerations and punctures to the arms, forearms, hands, fingers, legs, and thighs. Most injuries occurred while handling alligators, followed by wading or swimming, typically occurring in deep (>1 m) water, followed by shallow water, and within 1 m from shore.16 Most attacks occurred between the months of May and August and during the afternoon hours to twilight (Figure 58-5). Of the attacks in this study, 33% were felt to be provoked, with the majority of instances stemming from the victim trying to handle the alligator or trying to rescue another human or animal victim. The majority (54.8%) of cases were felt to be unprovoked.

In a series of 16 crocodile attacks reported from the Northern Territory of Australia, four fatalities involved transection of the torso or decapitation.19 Most attacks (fatal and nonfatal) were on persons swimming or wading in shallow water. A later study analyzing 62 definite, unprovoked attacks by wild saltwater crocodiles between 1971 and 2004 showed that 27.4% of attacks were fatal, with increasing numbers of attacks in recent years. Fatal injuries were equally likely to be during the day or night; however, nonfatal injuries occurred predominantly during the day (76.7%).3 Most attacks occurred in the wet-warm season during the months of November to April, with 51.6% of all annual attacks occurring during this time period. Most fatal attacks involved saltwater crocodiles greater than 4 m (13 feet) in length. Similar to U.S. studies, the majority of victims were male (75%), with an average age of 31.2 years.3

In riverine areas of Tanzania, crocodiles are a considerable health hazard. In the Korogwe District from 1990 to 1994, 51 human and 49 crocodile deaths were reported. The attacks are attributed to increased waste products in the water, which reduces the crocodiles’ primary food supply. In addition, “tamed” crocodiles are not hunted because of local superstitions and fear of reprisal by witchcraft.25 A study of attacks in Malawi noted that 60 patients were injured during a 4-month period.27 Twenty-four (40%) of the victims had significant injuries, including permanent deformity and one death from sepsis.

Smaller crocodilians generally bite only once, but one-third of attacks may involve repeated bites.15 Crocodilians greater than 2.5 m (8 feet) in length more commonly cause serious and repeated attacks, likely attributed to chasing or feeding behavior.15 Even though external injuries may appear to be only minor lacerations, underlying significant crush injuries often exist (Figures 58-6 to 58-8; Figures 58-7 and 58-8, online).14

First Aid

Crocodilian bites can produce large crush injuries, punctures, and lacerations. Polymicrobial infections have been found to commonly cause serious deformity, sepsis, and even death.12 Evaluation of every crocodilian attack victim should begin with evaluation of airway, breathing, and circulation. Although it is tempting to direct one’s attention to obvious bite wounds, more severe and life-threatening injuries, such as solid organ laceration, may exist that are less apparent. Once the airway has been secured, breathing assessed, and bleeding controlled, the patient should be completely examined from head to toe in order to discover other injuries. Basics of wound management consist of hemostasis, fracture stabilization, analgesia, thorough decontamination, and debridement1,13 (Box 58-1). Wounds should be copiously irrigated with clean water or sterile normal saline. Early analgesia will help facilitate patient comfort and debridement. If a patient is unlikely to receive hospital care shortly following an injury, empiric antibiotic therapy with a fluoroquinolone or cephalosporin should be initiated because culturing of fresh wounds immediately following injury has not demonstrated useful in antibiotic selection.10 Bony injuries or significant bleeding should prompt the application of splints to prevent further neurovascular injury and blood loss, improve pain control, and aid in transportation of the patient. Clean dressings should be applied to all open wounds.

Hospital Management

Early analgesia should be initiated, preferably with parenteral narcotics. In cases of severe deformity and pain not relieved by opiate analgesics, brachial plexus nerve blocks have been successfully used for wounds to the upper extremity.4 Small wounds may be anesthetized with local infiltration and nerve blocks. Severe cases with deep tissue destruction or multiple sites of injury may require general anesthesia to facilitate operative washout and debridement.

Initial evaluation of crocodilian attack wounds should include radiographs to assess for underlying fractures or tooth fragments. Further imaging with computed tomography (CT) may be warranted for further evaluation or operative planning. Patients with injuries to the head and neck, loss of consciousness, or severe scalp injuries should receive a CT scan to assess for intracranial or bony skull injury. Injuries in close proximity to a joint should be considered open until proved otherwise, with orthopedic consultation for possible exploration and washout. Areas concerning for compartment syndrome with associated symptoms of increased pain, tense compartments, and/or decreased signs of circulation or temperature should be evaluated with tissue manometry. Compartments with measured pressures >30 mm Hg should be referred for orthopedic evaluation and possible fasciotomy.18 Tetanus prophylaxis and an appropriate broad-spectrum antibiotic, such as a fluoroquinolone or cephalosporin, must be considered.

After exploration, irrigation, and debridement, bite wounds should preferably be left open because they are typically crush wounds or deep lacerations with significant bacterial contamination and surrounding soft tissue trauma.26 Cosmetically sensitive areas should be copiously irrigated and referred for delayed closure after 5 days of antibiotic therapy.26

Microbiology and Antimicrobials

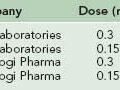

In a study of the oral flora of Alligator mississippiensis, more than 38 species of bacteria and 20 species of fungi were identified by culture techniques (Box 58-2).9 Prophylactic antibiotic therapy should be initiated to accomplish broad-spectrum coverage against gram-negative species, especially Aeromonas, anaerobes, and normal skin flora.9 The current recommendation is to give a fluoroquinolone, such as ciprofloxacin 400 mg IV every 12 hours or 500 mg orally every 12 hours, or a third-generation cephalosporin, such as ceftriaxone 1 g IV or IM every 24 hours.17 Adults with cephalosporin allergies can be treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 8 to 10 mg/kg/day of trimethoprim IV divided every 6 to 12 hours, or 160/800 mg orally twice daily, or a carbapenem such as imipenem/cilastatin 500 mg IV every 6 to 8 hours, for a maximal dose of 50 mg/kg/day.24 There has not been any good study evaluating duration of antibiotic treatment. Soft tissue infections should generally be treated for 7 to 10 days but may require a longer duration of antibiotic therapy for bone or connective tissue involvement.

Special attention is given to treating Aeromonas infection, as this can become fulminant and rapidly progress within 24 to 48 hours to cellulitis, bullae formation, local necrosis, and sepsis. There have been case reports of Vibrio vulnificus infections following alligator attacks. V. vulnificus exists in marine and estuarine environments and causes lesions presenting with hemorrhagic bullae or vesicles followed by necrotic ulcers.2,16 These wounds should be surgically drained and treated, at a minimum, with doxycycline in addition to empiric therapy.17 Suspected or established Vibrio or Aeromonas infection should be treated as discussed in Chapter 79.

Prevention

The alligator population is increasing in the United States, with nuisance complaints now registered yearly in the thousands (Box 58-3).16 In Florida, the number of nuisance calls related to alligators increased from 4914 in 1987 to 18,307 in 2006.16 These alligators are often moved to other areas or harvested. For example, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission permits the killing of approximately 7000 nuisance alligators each year.11

Persons in the United States traveling to regions inhabited by crocodilian species should exercise extreme caution, especially around the months of May and June, because this is breeding season and roughly 34% of attacks are felt to be defensive in nature.16 Most attacks occur in the deep or shallow regions of slow-moving water or in muddy areas within one meter of shore. Crocodilians are more active during temperatures between 28° and 33° C (82.4° and 91.4° F) and become more dormant below 12.8° C (55° F).28 Crocodilians may quickly become habituated to humans, and travelers should avoid areas where these animals are fed. Caution should be used when traveling with pets because small cats and dogs are natural prey. People should be aware of the locations and activities of small children, and not allow them to approach bodies of water outside of posted swimming areas. Avoid outdoor swimming at dawn or dusk, or during nighttime. Do not throw fish or scraps of food into the water. Do not remove crocodilians from their natural environment or keep one as a pet.

1 Brook I. Management of human and animal bite wound infection: An overview. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2009;11:389.

2 Bross MH, Soch K, Morales R, et al. Vibrio vulnificus infection: Diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:539.

3 Caldicott DG, Croser D, Manolis C, et al. Crocodile attack in Australia: An analysis of its incidence and review of the pathology and management of crocodilian attacks in general. Wilderness Environ Med. 2005;16:143.

4 Chiu CH, Kuo YW, Hsu HT, et al. Continuous infraclavicular block for forearm amputation after being bitten by a saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus): A case report. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2009;25:455.

5 Conover M. Resloving human-wildlife conflicts: The science of wildlife damage management. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2002.

6 Cott H. Scientific results of an enquiry into the ecology and ecommonic status of the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) in Uganda and northern Rhodesia. Trans Zool Soc Lond. 1961:2117.

7 Davidson IS. Was OH7 the victim of a crocodile attack? Tempus. 1990;2:1976.

8 Dudley K. Alligators and crocodiles. Calgary: Weigl Educational Pulblishers Limited; 1998.

9 Flandry F, Lisecki EJ, Dominique GJ, et al. Initial antibiotic therapy for alligator bites: Characterization of the oral flora of Alligator mississippiensis. South Med J. 1989;82:262.

10 Fleisher GR. The management of bite wounds. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:138.

11 Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission: A guide to living with alligators, 2010.

12 Harding BE, Wolf BC. Alligator attacks in southwest Florida. J Forensic Sci. 2006;51:674.

13 Hertner G. Caiman bite. Wilderness Environ Med. 2006;17:267.

14 Howard RJ, Burgess GH. Surgical hazards posed by marine and freshwater animals in Florida. Am J Surg. 1993;166:563.

15 Langley RL. Alligator attacks on humans in the United States. Wilderness Environ Med. 2005;16:119.

16 Langley RL. Adverse encounters with alligators in the United States: An update. Wilderness Environ Med. 2010;21:156.

17 Lopez FA. Skin and soft tissue infections. In: Betts RF, Penn RL, editors. A practical approach to infectious diseases. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.

18 Masquelet AC. Acute compartment syndrome of the leg: Pressure measurement and fasciotomy. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2010;96:913.

19 Mekisic AP, Wardill JR. Crocodile attacks in the northern territory of Australia. Med J Aust. 1992;157:751.

20 Oxenham M. Forensic approaches to death, disaster and abuse. Australia: Australian Academic Press; 2008.

21 Raynor AC, Bingham HG, Caffee HH, et al. Alligator bites and related infections. J Fla Med Assoc. 1983;70:107.

22 Rheinheimer G. Aquatic microbiology. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2007.

23 Rosenthal SG, Bernhardt HE, Phillips JA3rd. Aeromonas hydrophila wound infection. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1974;53:77.

24 Sartain SESteele RW. An alligator bite. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2009;48:564.

25 Scott R, Scott H. Crocodile bites and traditional beliefs in Korogwe District, Tanzania. BMJ. 1994;309:1691.

26 Trott A. Wounds and lacerations: Emergency care and closure, ed 3. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2005. xiv, p 386

27 Vanwersch K. Crocodile bite injury in southern Malawi. Trop Doct. 1998;28:221.

28 Woodward AR. Prevention and control of wildlife damage. Cooperative Extension Division, Institute of Agricultural and Natural Resources. Lincoln, Neb: University of Nebraska; 1994.